29: 先天性鞘膜积液与腹股沟疝

阅读本章大约需要 3 分钟。

引言

本章将尝试以全面而又简明扼要的方式,介绍先天性腹股沟疝和鞘膜积液的历史、胚胎学与发育、诊断与治疗。我们将强调与该主题不同方面相关的细节,并为读者提供有用的提示,以便对该疾病采取恰当的管理策略。

病史

下文所述的时间线强调了与先天性腹股沟疝和鞘膜积液相关的历史里程碑和随时间取得的进展(图 1)

公元25年,塞尔苏斯首次记载了儿童疝气修补术。

医学以及术后患者护理的进步,随着时间的推移,改进了手术技术并改善了手术结局。如今,该手术在全球范围内的实施大体相似,仅有少量差异,主要取决于术者偏好以及所选择的修复方式(腹腔镜与传统开放)。

图 1 时间线

胚胎学

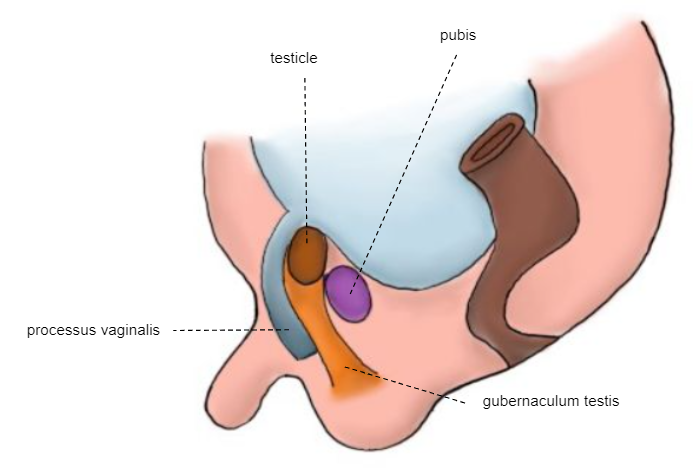

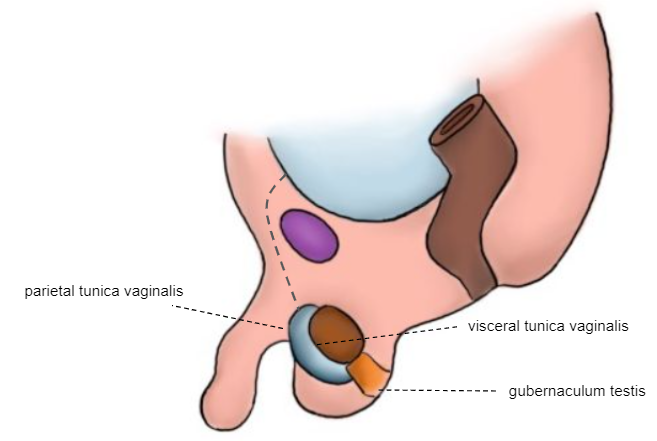

鞘膜积液和先天性腹股沟疝的发生源于腹膜鞘状突(PV)闭锁过程失败;该结构为由体腔上皮形成的腹膜外突,正常情况下在生后第一年内闭锁。

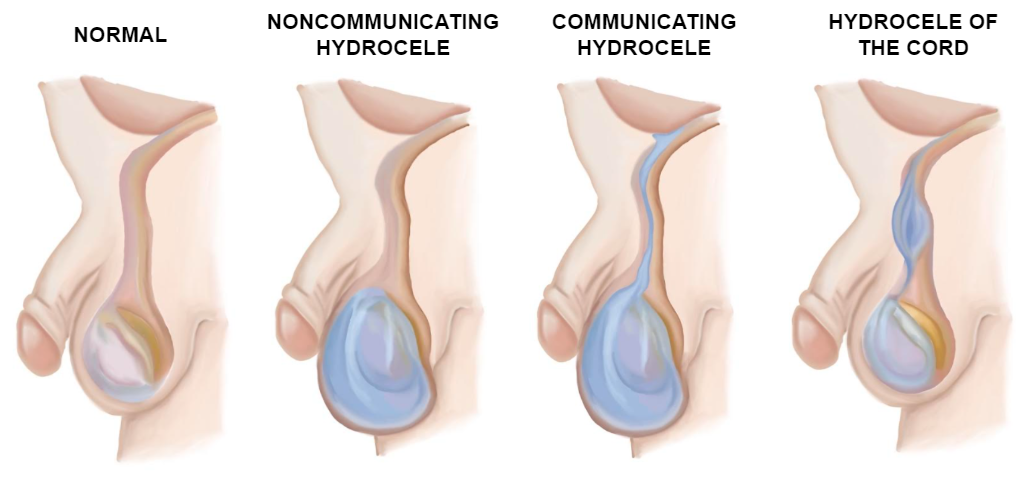

鞘膜积液可定义为当鞘状突(PV)持续未闭时,在鞘膜(TV)的壁层与脏层之间出现的液体聚集。它可分为交通性、非交通性和精索鞘膜积液。如果该管腔足够宽,腹腔内容物可能疝入其中,形成腹股沟疝。1

在胎儿期晚期,睾丸和卵巢所处的位置与胚胎期不同。睾丸的位置变化比卵巢明显得多,其中包括其穿过腹壁全层下降至阴囊的过程。2

在男性中,调控睾丸发育及其随后下降的事件包括:

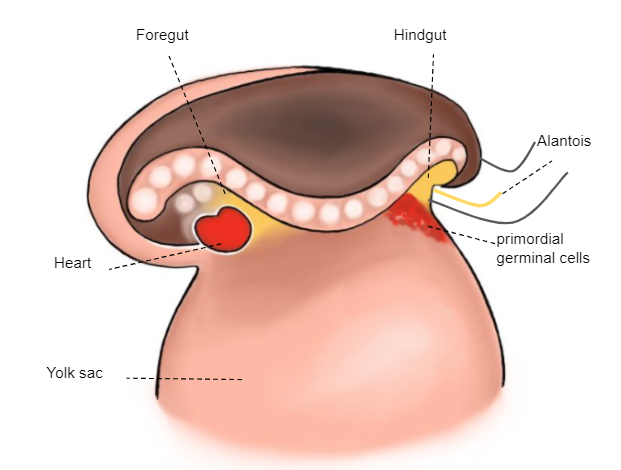

第3周

位于卵黄囊壁的原始生殖细胞(胚外配子)向性腺嵴迁移(图 2)

图 2 第3周胚胎

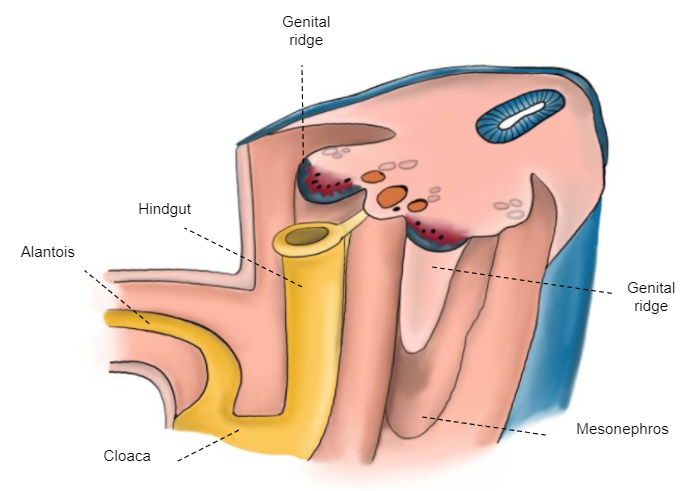

第6周

未分化的性腺通过生殖腺系膜附着于后壁,该系膜在头侧形成膈韧带,在尾侧形成腹股沟韧带(gubernaculum) (图3)

图 3 第6周胚胎

第7-8周

性索穿入髓质并形成睾丸索,这些睾丸索到达睾丸系膜并形成睾丸网 (Haller's network)。随后,它们转变为输出管索。 (图 4)

图 4 第7–8周胚胎

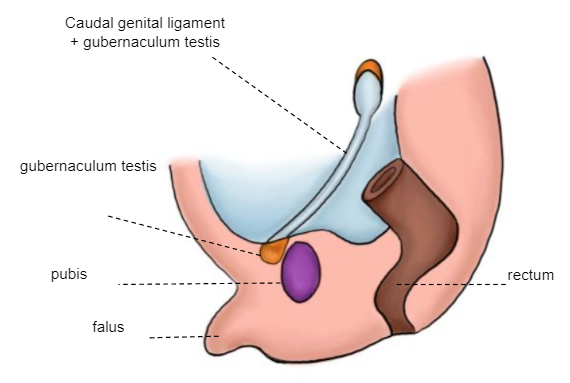

第10至12周

睾丸引带远端附着于阴唇阴囊隆起,其将作为中胚层围绕其塑形的轴心,进而形成腹股沟管。沿着睾丸引带朝向阴唇阴囊隆起的轨迹,形成一个腹膜外突——鞘状突(体腔上皮)。发生了睾丸下降的第一阶段,在此阶段中,睾丸从其腰部位置移至腹股沟浅环附近(图 5)。

图 5 10–12周胚胎

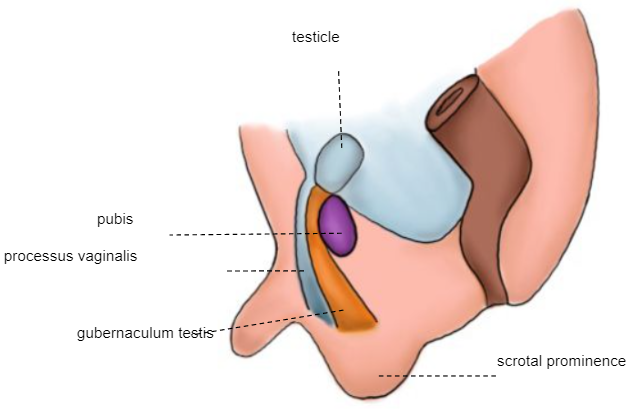

第28周

下降的第二阶段: 睾丸穿过已形成的腹股沟管,在第32至35周之间到达阴囊 (图 6)

图 6 第28周胚胎

足月新生儿

睾丸固定于阴囊 (图 7)

这些可能触发睾丸下降的机械因素到阴囊包括:

- 由睾丸引带产生的远端牵拉力。

- 腹腔内压力。

其他可能的决定因素包括激素和神经因素。2

图7 新生儿

如前述连续的胚胎学图示所示,腹膜鞘状突(PV)在出生前不久开始闭锁。通常在生命的第一年内可实现完全闭锁。睾丸鞘膜(TV)继续包绕睾丸。PV的闭锁过程若失败,则与疝、鞘膜积液以及精索囊性鞘膜积液有关。

流行病学

足月新生儿先天性腹股沟间接疝的发生率为3.5–5%,而在早产儿中则明显更高,范围为9–11%。当出生体重降至500–750克时,其发生率接近60%。大多数病例系列报告男性较女性占优势,比例为5:1至10:1。3

另一方面,交通性鞘膜积液在新生儿中很常见,发生率为2–5%;其中90%在生命的第一年因自发闭合而自行消退。4

先天性腹股沟疝更常见于右侧(60%),30%发生于左侧,10%为双侧。这种分布不随性别改变,因为即使在女童中也以右侧为主。5

病因 / 发病机制

腹股沟管的解剖结构随年龄略有差异。在成人和儿童中,腹股沟深环与浅环相距较远;而在年幼婴儿中,它们几乎重叠。在女童中,解剖结构相似,但缺乏精索成分,由子宫圆韧带所替代。3 不同类型的鞘膜积液见下图 (图 8)

图 8 鞘膜积液的类型

如前所述,先天性间接腹股沟疝可由通畅的PV形成,使大网膜、肠管、阑尾,甚至女性的卵巢或输卵管经腹股沟管脱出。疝囊也可能自腹腔经腹股沟内环向下延伸至TV,形成所谓的腹股沟阴囊疝。

直接腹股沟疝在儿科人群中非常罕见,它们多见于成年人,原因是腹壁后部肌肉无力,使肠管滑入腹股沟。

诊断与评估

腹股沟疝和鞘膜积液无需严格依赖影像学检查,即可通过体格检查作出诊断。男孩在腹股沟或阴囊出现可复性、无症状且质地较硬的隆起,或女童大阴唇出现肿块,均提示腹股沟疝的可能。

当患者出现剧烈、突发性疼痛,并在腹股沟触及坚硬、压痛且固定的肿块时,应怀疑疝囊嵌顿。若不能手法复位,则应进行手术复位。6,7

体格检查应包括在仰卧位对患者进行评估,若可行,可辅以瓦尔萨尔瓦动作以识别一过性疝;以及在站立位进行评估,医生应触诊并比较双侧腹股沟,以查找腹股沟索增粗或膨隆。在男性患者中,应检查睾丸是否已正常下降,透照试验(将光源置于阴囊上,显示无睾丸阴影)有时有助于确认鞘膜积液。

提示

- 在触诊时,最重要的是在指腹下感觉到精索滑动。

- 我们建议用最熟练的那只手触诊精索。

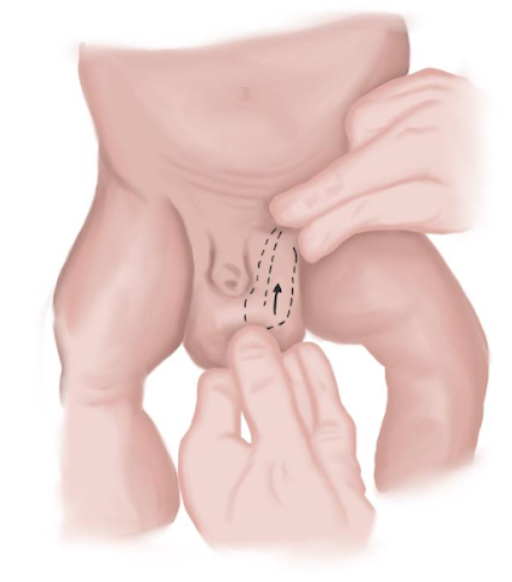

- 在新生儿中,疝更常能被复位。应使用熟练的那只手将疝内容物向上挤压,同时用另一只手向下施压,使两处腹股沟环对齐,并将疝内容物引导回腹腔内 (图9)

图 9 新生儿疝复位手法。

如果体格检查不能确诊,腹股沟超声检查可为疑诊提供补充信息。8 尽管如此,体格检查仍是诊断的金标准。超声的敏感性主要取决于操作者的技术水平以及患者的配合(保持静止和进行瓦尔萨尔瓦动作)。疝内容物可因网膜脂肪而呈高回声,在存在液体时呈无回声,或表现为伴有混响伪影的混合回声,这与肠袢腔内存在气体相对应。9 超声还可用于排除对侧腹股沟疝,或可在同台手术中修补的PV。

鉴别诊断

腹股沟病变的鉴别诊断常常具有挑战性,因为体格检查中的征象相似。一旦发现可触及且有压痛的肿块,医师应考虑以下可能的诊断;若仅凭体格检查不足,应辅以其他补充性检查:

- 隐睾。

- 血肿 / 炎症。

- 脓肿。

- 良性或恶性肿瘤 / 转移性或良性淋巴结肿大。

- 圆韧带静脉曲张。

- 间皮囊肿。

治疗选项

腹股沟疝的治疗一律采用手术方式,治疗的关键是行疝囊高位结扎。

在婴儿和幼儿中,由于内、外环通常彼此重叠,可经腹股沟外环在无需切开外斜肌腱膜的情况下完成疝囊高位结扎术。在年长患儿中,内、外环彼此分离。此时宜切开外斜肌腱膜,以便对疝囊行高位结扎。3 在儿科患者中,腹壁网片的使用仅限于特殊情况。

对于鞘膜积液和腹股沟疝,两者的手术原则和技术非常相似。对鞘膜积液行手术治疗时,除疝囊高位结扎外,其远端部分也应切除。此步骤对腹股沟疝并非必需。

腹股沟疝可采用开放式腹股沟疝修补术(OIH)或腹腔镜腹股沟疝修补术(LIHR)。手术最重要的环节包括:确保术中疝囊被清空并完全闭合,并保护输精管、睾丸血管及髂腹股沟神经的完整性。在女孩中,应进行圆韧带固定以确保子宫正确固定,预防今后出现性交痛。

开放式腹股沟疝修补术

下文详细介绍 OIH 的主要步骤,并附有操作示意图。

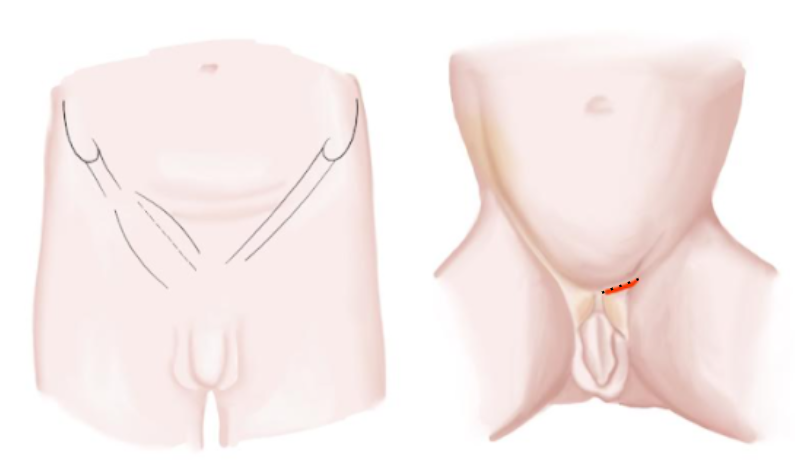

- 沿自然皮肤皱褶,于精索上方行横向腹股沟切口(图 10)

- 分离皮下蜂窝组织,切开Scarpa筋膜,直达肌腱膜。

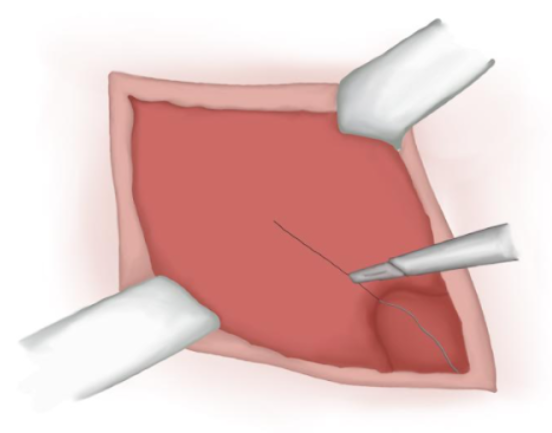

- 于肌腱膜上切开(并非总是需要)(图 11)

- 将腱膜切口向浅腹股沟环方向延长。

- 以钝性手法分离精索的两侧及下方。随后用弹性圈进行固定z。

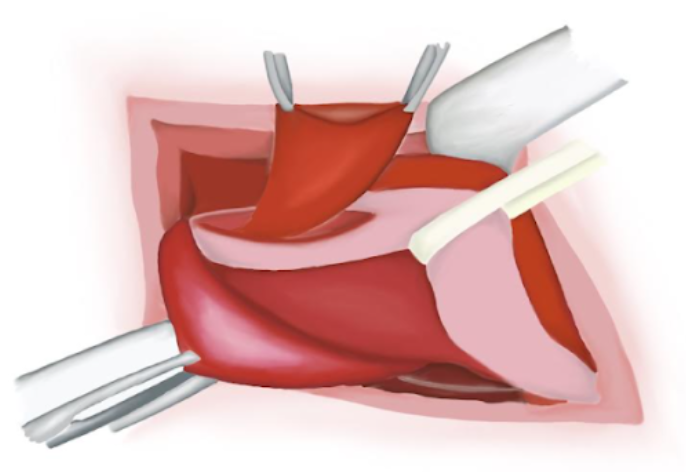

- 在精索的前内侧面以钝性分离剥开提睾肌,并将其分离展开,以显露间接疝囊光亮的腹膜(图 12)。

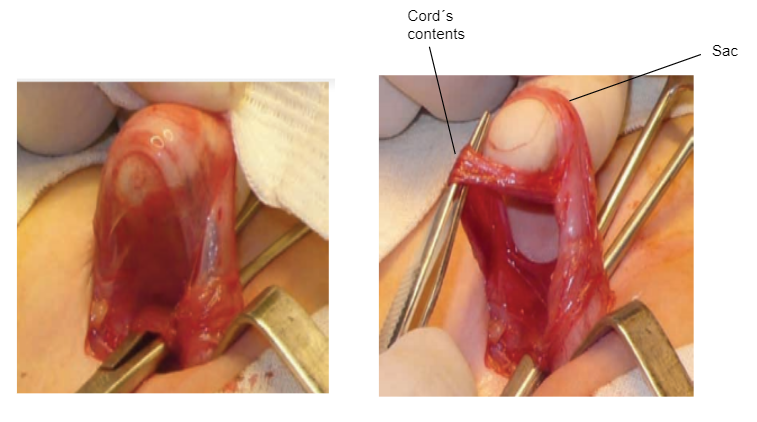

- 轻柔分离精索及其内容物(血管、输精管),使其与位于前内侧的疝囊分开。

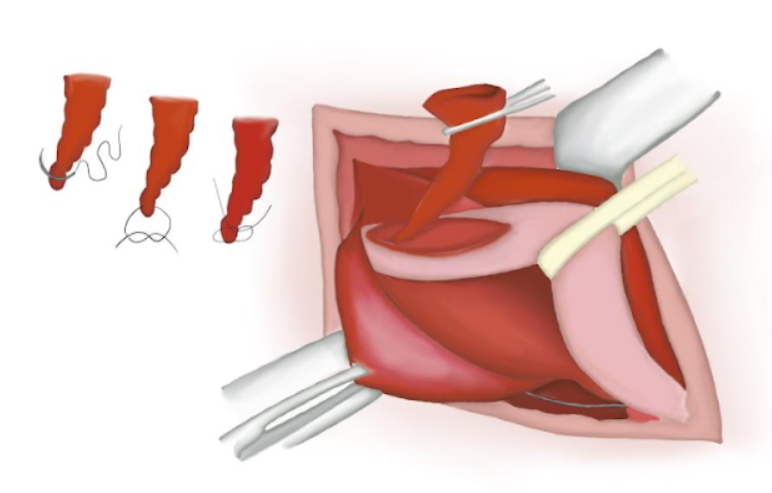

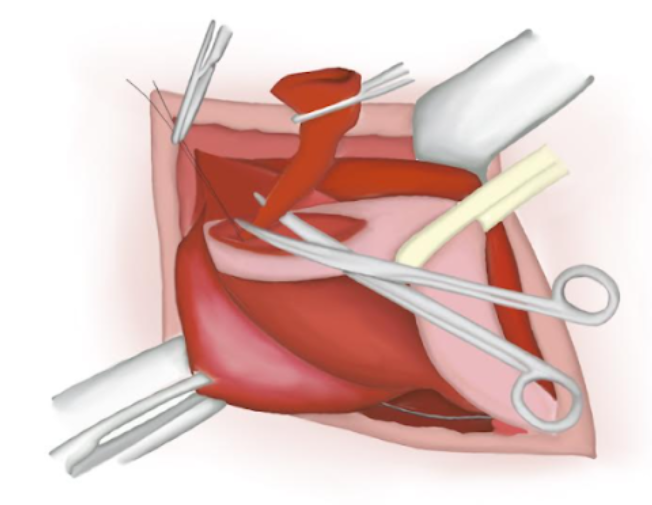

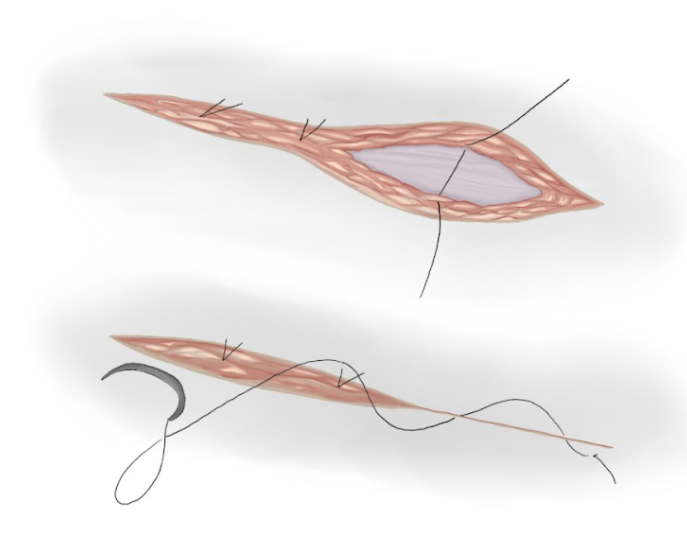

- 将精索的内容物谨慎与疝囊分离,并将疝囊自其上剥离(图 13)。

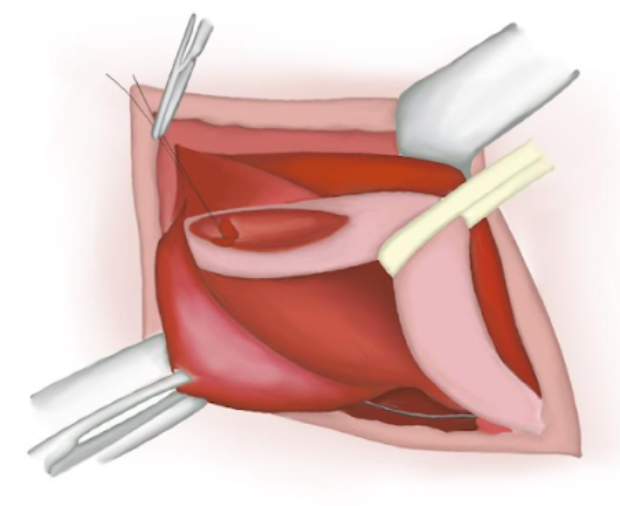

- 打开疝囊,将其内容物复位于腹腔。

- 扭转疝囊,确认其内无内容物。在囊基部以可吸收聚乙交酯线结扎,随后切断疝囊并使其回纳入腹腔(图 14)、(图 15)和(图 16)。

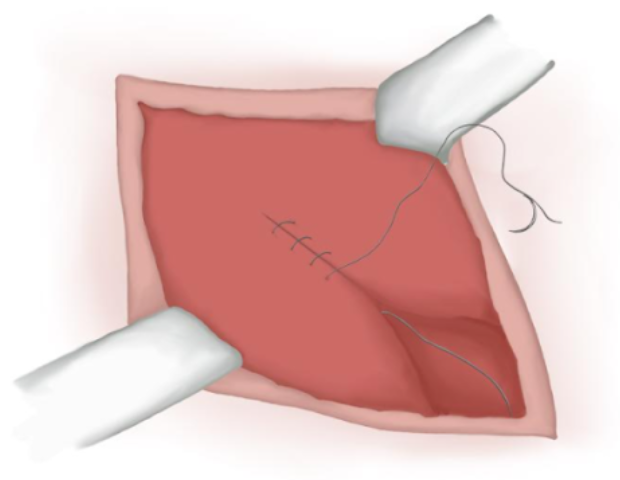

- 如已切开,则以连续可吸收聚乙交酯缝线缝合肌腱膜(图 17)。

- 以间断结缝合使皮下组织对合,并以皮内缝合使皮肤对合(图 18)。

图 10 婴儿和青少年的腹股沟切口

图 11 在肌腱膜上的切口。

图 12 精索识别。疝囊分离。

图 13 疝囊分离。

图 14 将疝囊扭转,确保囊内无内容物。

图 15 疝囊已切除。

图 16 已缝合的近端丢失于腹腔内。

图 17 肌腱膜闭合。

图 18 皮下及皮肤缝合。

提示

- 作者建议沿皮纹行横行皮肤切口。

- 在更复杂的病例(双侧疝的女童、肥胖儿童)中,于腱膜平面寻找股弓,以定位腹股沟浅环。

- 按规范始终在精索的同一侧分离疝囊

腹腔镜下腹股沟疝修补术

腹腔镜腹股沟疝修补术的地位尚未完全确立。该方法被批评为将腹膜外手术转变为经腹膜手术。反对者认为,该技术在技术上更为复杂,且其复发率高于传统方法。

相反,腹腔镜入路的倡导者强调,该技术可降低侵袭性,无需操作精索结构,并有助于对伴发的直疝和股疝作出正确诊断。此外,对侧内环可被清晰显露,并在必要时进行修补。最后,支持者认可与传统切口相比,此手术后的美容效果更佳(表 1)。10

表 1 下表展示了关于LIHR的一些优点和缺点:

| 优点 | 缺点 |

|---|---|

| 技术简便易行。 | 费用。 |

| 门诊手术。 | 手术时间可能更长。 |

| 精索结构不被触及。 | 需要全身麻醉并气管插管。 |

| 疝的类型以及对侧腹股沟环清楚可见。 | 腹腔内器官损伤的可能性增加。 |

| 解剖结构可清晰显示。 | 学习曲线更长。 |

| 可检查女童附件。 | 远期可能出现精索损伤 |

术后护理与随访

由于这是日间手术,术后在麻醉恢复后即可开始进食和饮水。合并支气管肺发育不良、贫血、早产,或出生时需要呼吸支持的婴儿,手术修复后应观察至少24小时,并监测是否出现呼吸暂停和/或心动过缓事件。患者应带口服镇痛药出院。

活动应限制48小时。一旦孩子觉得可以,即可恢复正常活动。对于超过6岁的儿童,活动限制应更严格,在1个月内不进行剧烈活动。术后第3天可以开始洗澡。

术后1周应进行随访以评估早期并发症,随后在术后1个月、3个月和6个月进行临床复查,之后出院。

结局、并发症与处理

在手术过程中,局部并发症包括出血以及对精索血管和输精管的损伤。对术中损伤进行重建时使用手术放大镜将使修复更为精确,尤其是在新生儿中。

术后早期并发症可能包括局部水肿、血肿和切口感染。

随访期间可见的迟发并发症可能包括复发性鞘膜积液或腹股沟疝、医源性睾丸移位以及睾丸萎缩。为避免术后鞘膜积液,可部分切除囊的前壁和侧壁,或将远端囊完全开放。

在未满1岁时接受手术的男性患儿以及采用腹腔镜途径处理的病例复发率更高。若由技术娴熟、经验丰富的小儿外科医生或小儿泌尿外科医生实施,或作为择期手术进行,则复发率可显著降低。

儿童复发性腹股沟疝可能包括:

- 漏诊的疝囊或未识别的腹膜撕裂。

- 对疝囊的不当结扎。

- 未修补大的腹股沟内环。

- 未识别的腹股沟管底缺损(直接腹股沟疝)。

- 感染。

- 腹腔内压升高(行脑室-腹腔分流或持续性可携带式腹膜透析的患者)。

- 患有囊性纤维化及慢性咳嗽的患者。

- 结缔组织疾病(即埃勒斯-当洛斯综合征)。

要点

- 关于腹股沟疝的文献已延续20多个世纪。盖伦在公元176年首次描述了间接腹股沟疝的发病机制,并首次描绘了 “Processus Vaginalis Peritonei“。

- 发病率 足月新生儿先天性间接腹股沟疝的发生率为3.5–5%,而早产儿为9–11%。

- 流行病学: 多见于男性,男:女比范围为5:1到10:1。

- 诊断 腹股沟疝和鞘膜积液均可通过体格检查作出诊断,且无需严格依赖影像检查即可予以确认。

- 治疗 腹股沟疝的治疗一律为手术治疗。可采用开放式腹股沟疝修补术(OIH)或腹腔镜腹股沟疝修补术(LIHR)。

- 手术治疗通常为日间手术。合并支气管肺发育不良、贫血、早产,或出生时需要呼吸机支持的婴儿,术后应观察至少24小时。

- 随访 术后1周随访以评估早期并发症,随后于术后1个月、3个月和6个月进行临床复查。

- 早期并发症 术后可能包括局部水肿、血肿和伤口感染。

- 晚期并发症 随访期间可见复发性鞘膜积液或疝、医源性睾丸移位以及睾丸萎缩。

结论

腹膜鞘状突未闭(PV)会导致先天性鞘膜积液和腹股沟疝。腹股沟可触及肿块者应评估是否存在与PV相关的疾病。体格检查是这些疾病的诊断金标准。对腹股沟疝及合并疝的交通性鞘膜积液,治疗一律为手术。手术治疗的成功取决于对囊颈的高位结扎,以及在鞘膜积液时对其远端部分的切除。手术方式包括开放性腹股沟疝修补术以及腹腔镜手术。

并发症可发生于手术期间或术后早期或晚期,分别包括水肿、血肿、复发性鞘膜积液或疝。专家为避免上述并发症提出了多种策略。随访应定期进行,至少持续6个月。

关于疝和鞘膜积液的管理仍存在争议,尤其是在以复发率和并发症发生率为依据选择手术技术、力求采用微创并获得更佳临床结局方面。

参考文献

- Gearhart JP, Rink RC, Mouriqand PDE, editors. Pediatric Urology. 2nd ed., Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2010, DOI: 10.1097/00042307-200011000-00007.

- Palermo M. Hernias de la pared abdominal - Conceptos clásicos, evidencias y nuevas técnicas. Actualidades Médicas, C.A: AMOLCA; 2012.

- J. T. Chapter 59: Inguinal Hernia. In: Puri P, editor. Newborn Surgery. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2003. DOI: 10.5005/jp/books/12263_1.

- Godbole P.P. MNP. Chapter 18: Testis, Hydrocele and Varicocele. In: Wilcox DT, Thomas DFM, editors. Essentials of Pediatric Urology. 2nd ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2021. DOI: 10.1201/9781003182023.

- Rowe MI, Clatworthy HW. The other side of the pediatric inguinal hernia. Surg Clin North Am 1971; 51: 1371. DOI: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)39592-5.

- Choi KH, Baek HJ. Incarcerated ovarian herniation of the canal of Nuck in a female infant: Ultrasonographic findings and review of literature. Annals of Medicine and Surgery 2016; 9: 38–40. DOI: 10.1016/j.amsu.2016.06.003.

- Stringer MD, Oldham KT, P.D.E. M, editors. Pediatric Surgery and Urology Long-term Outcomes. 2nd ed., Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2010.

- Park HR, Park SB, Lee ES, Park HJ. Sonographic evaluation of inguinal lesions. Clinical Imaging 2016; 40 (5): 949–955. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2016.04.017.

- Yang DM, Kim HC, Lim JW, Jin W, Ryu CW, Kim GY. Sonographic findings of groin masses. J Ultrasound Med 2007; 26: 605–614. DOI: 10.7863/jum.2007.26.5.605.

- Holcomb GW, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SE, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-84467-7_61.

最近更新时间: 2025-09-22 08:00