25: Duplex Urethral Anomalies and Syringocoele

阅读本章大约需要 13 分钟。

Introduction

Urethral anomalies are congenital disorders that are not uncommon, with some rare variations. This chapter will focus on embryology, epidemiology, diagnosis, evaluation, repair, follow-up, and complications of some anterior urethral anomalies, including anterior urethral valve (AUV), syringocele, urethral duplication and megalourethra. Some even believe that these anomalies, except duplication, are the same and a spectrum.

Embryology

Male urethral development originates with the urogenital sinus cavity extending onto the surface of the genital tubercle during week 6 of gestation. This endodermal derived groove becomes a solid plate of cells, which eventually tabularises in proximal-to-distal fashion to form the phallic urethra. The appearance is identical in male and female fetuses until week nine, and by week 14, the male urethra is complete in its development. The urethra has been divided into four distinct regions, each with its unique anatomical classification and predominant histological cell type of the urethral mucosa. The prostatic urethra and membranous urethra are most proximal, derived from the urogenital sinus and composed of delicate transitional epithelium. Next is the bulbar and pendulous urethra, derived from the urethral plate on the ventral aspect of the genital tubercle and lined with transitional epithelium proximal, changing to simple squamous epithelium distally. The most distal pendulous urethra is also known as the fossa navicularis, also derived from the urethral plate as it traverses the glans penis but is composed of stratified squamous epithelium.

Epidemiology

The ratio of the incidence of AUV to that of posterior urethral valves (PUV) is 1:8; PUV occurs in 1 in 8000 to 1 in 25,000 live male births. Diverticula of the anterior urethra are uncommon but are the second most common form of congenital urethral obstruction, after PUV, in infants and children. Fewer than 50 cases of megalourethra had been reported in the literature by 1993, the scaphoid type being more common. Both Cowper’s duct cysts and congenital urethral polyps are quite rare.

Anterior Urethral Valves

Anterior urethral valves are the most common congenital obstructive lesion of the anterior urethra but are 25-30 times less common than PUVs. As classically described, these take the form of either a fenestrated diaphragmatic membrane or a mucosal cusp arising from the ventral wall of the urethra. The embryology is unclear because anterior urethral valves are occasionally found at the distal end of a diverticulum. However, hypoplastic corpus spongiosum over the affected portion of the anterior urethra indicates a place on the hypospadias spectrum or a faulty union between urethral mucosa and the epithelium of the fossa navicularis. A rupture of dilated bulbourethral glands has also been suggested as an aetiology. These valves may be located anywhere in the anterior urethra. In 40%, it is sited at the bulbar urethra, 30% at the penoscrotal junction and 30% in the penile urethra. They have rarely been reported in the fossa navicularis. The presentation is usually with obstructive symptoms. These patients commonly have urine dribbling, difficulty voiding, incontinence, hesitancy or urinary retention, poor urinary stream, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Older children may also have enuresis, postvoid dribbling, or failure to thrive. Secondary changes in the upper urinary tract are rare. However, the obstruction may result in megacystis, bladder rupture, severe hydroureteronephrosis, acute kidney injury, or urinary ascites in the neonatal period. Micturating cystourethrography (MCUG), retrograde urethrography, and endoscopy are useful diagnostic tools. On MCUG, the valve itself may be visualised as a linear defect along the ventral wall but may only be noted as an abrupt change in the caliber of the urethra.

Vesicoureteral reflux has been noted in approximately one-third of patients, and upper tract dilation was noted in half. Endoscopically, the valve appears as a filmy, ventrally located cusp or flap of tissue, and it occasionally has been described as an iris-like membrane. One must scrutinise the urethra at the distal end of any urethral diverticulum because the retrograde flow of the irrigant may flatten the valve mechanism against the urethral wall. Suprapubic pressure with the bladder full and irrigation ports on the scope open may demonstrate the valve mechanism more readily.

Furthermore, the elevation or engaging the valve with an endoscopic loop is invaluable in identifying the lesion. Transurethral incision of the valve is adequate for most patients, but one must be careful to incise completely to avoid any distal obstructing lip. Endoscopic treatment does leave the patient with a urethral diverticulum in most cases. An occasional patient with a large diverticulum and a defect in the spongiosum may benefit from open repair, which allows reconstruction of the valve, diverticulum, and investing tissues. A vesicostomy may be required in a premature or small infant to facilitate relief of obstruction until the infant can accommodate a cystoscope or undergo further reconstruction. Up to 80% of children with anterior urethral valves will develop bladder dysfunction, instability, hyperreflexia, and diminished compliance and capacity noted on urodynamics. Because of the milder and more subtle presentation, the overall incidence of preserved renal function in AUV is better than PUVs, with around 78% of patients having normal renal function after treatment.

Urethral Diverticulum

In the more common wide-mouthed form, usually located in the region of the penoscrotal junction, the distal lip may give rise to a form of valvular obstruction as the diverticulum undergoes progressive distension. Presentation is either with obstructive symptoms or with post-micturition dribbling. The rarer saccular lesions have a narrow neck and may occur anywhere along the length of the penile urethra, including the fossa navicularis. Presentation is with urinary infection; rarely associated with stone formation within the diverticulum. Treatment is by endoscopic incision or resection of the obstructing lip or, rarely, by an open perineal approach to excising a large diverticulum.

Megalourethra

It is a rare congenital anomaly characterised by abnormal dilatation of the penile urethra without clear obstruction. It may be associated with a lack of corpus spongiosum or the complete absence of the corpora cavernosa. In such cases, the penis amounts to little more than a floppy sac comprised of skin externally and urethral mucosa internally. It shares some of the characteristics of a urethral diverticulum but includes more extensive and uniform involvement of the urethra. The classification of fusiform and scaphoid types reflects the severity of the defect and the resultant effect on the corpus spongiosum and cavernosum. The scaphoid form results from deficiency or absence of the ventral corpora spongiosum. A fusiform megalourethra also affects the dorsal spongiosum and corpora cavernosa. Adamson and Burge have described a third type with all corpora intact. The cause of megalourethra remains somewhat controversial. Stephens postulated that a delay in the canalisation of the distal epithelial core might lead to obstruction and proximal dilation. Others have suggested that embryological arrest of the mesoderm investing the urethral folds influences the corpora and erectile tissue development.

Figure 1 Examination under anesthesia showing large megalourethra involving the penile shaft.

Megalourethra is often associated with other urorectal anomalies such as imperforate anus, prune-belly syndrome, and urethral valves and with varying degrees of obstructive uropathy. Diagnosis is often suspected on physical examination, mainly if the child is seen to void. The urethral meatus may be normally placed but pathological. A soft, elongated phallus often characterises the rare and more severe fusiform type with palpably inadequate corpora. Ventral ballooning with voiding is typical of scaphoid megalourethra. Voiding cystourethrography and renal ultrasonography are performed to establish the diagnosis and evaluate the upper tracts. Treatment centers on reconstructing the urethra and corpus spongiosum using standard principles of hypospadias repair. The scaphoid urethra can be opened longitudinally and tabularised using the better dorsal and lateral tissue. The fusiform variety presents a much more difficult challenge depending on the amount of corporal tissue present. Some may be impossible to completely repair from a functional standpoint and benefit from corporal reconstruction with penile prostheses as adults.

Syringocoele

Syringocoele (from "syrongos", meaning tube and "coele", meaning swelling) is a rare cystic dilatation of the distal portion of Cowper’s gland ducts. The gland was named after the surgeon and anatomist William Cowper, who first described it in the 17th century. Cowper's glands are homologous to the Bartholin's glands in females. These exocrine glands are paired bulbourethral glands lying on either of the membranous urethrae. The main glands lie on the urogenital diaphragm, and the accessory glands lie deeply within the spongy bulbar urethra. The ducts of these glands pass through the external sphincter and enter the bulbous urethra, opening separately or as a single united duct one to two centimetres (cm) more distally. The glands produce mucoid secretion during sexual arousal and forms part of the pre-ejaculate that helps to lubricate the urethra for the passage of spermatozoa.

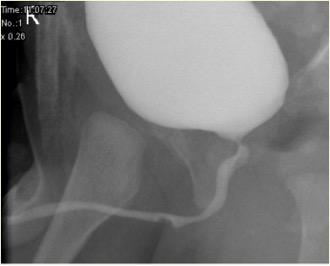

Figure 2 Unruptured syringocele appearance in MCUG

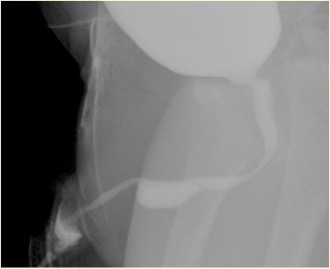

Figure 3 Ruptured syringocele appearance in MCUG

The true incidence of syringocoele is unknown and could be due to the rarity and unfamiliarity with this condition compounded by the existence of alternate diagnoses such as a false passage, urethral diverticulum, or anterior urethral valve, and in some, the potential for spontaneous resolution. Obstructions of the ductal orifice are either congenital or acquired. The proliferation of the ductal epithelium results in congenital retention cysts and pre-stenotic ductal dilatation.

Infection or repeated urethral catheterisation are causes for acquired obstruction. Syringocoele is rare and may present with recurrent urinary infections, hematuria, obstructive symptoms, or post-void dribbling. Rarely it can be an incidental finding. Significant bladder outflow obstruction due to a syringocoele in early life can lead to chronic kidney disease and bladder dysfunction. For all patients, therefore, early diagnosis and prompt treatment are vital. A helpful classification considers the aspects of clinical presentation and patient management. The groups are obstructive, non-obstructive symptomatic and non-obstructive asymptomatic. The obstructive group would include all patients presenting with either signs or symptoms or radiographic or endoscopic evidence of bladder outflow obstruction. Presentation is usually in early infancy.

Associated abnormalities include thick wall bladder, multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), dysplastic kidney and pelvi-ureteric junction (PUJ) obstruction. Micturating cystogram (MCUG) is a diagnostic test that can show a "filling defect" appearance of the urethra (unruptured syringocoele) or contrast filling the ruptured cyst with bladder trabeculation, VUR and incomplete emptying. A cystoscopic examination can be confirmatory. Endoscopic management uses various techniques to treat syringocoeles, namely Bugbee electrode, scissors, hooked urethral catheter, catheterisation, and Holmium: YAG Laser. During endoscopic management, unruptured syringocoeles are laid open, and the lips of all the ruptured syringocoeles can be incised. Syringocoele is not an inconsequential condition in infants, and all patients must be treated appropriately and followed up closely. In pediatric urology practice, syringocoele must be considered in evaluating anterior urethral obstruction. Close follow up of patients with syringocoele is necessary as up to 40% have renal impairment, of whom nearly two-fifths progress to chronic renal failure. A minority have bladder dysfunction.

Urethral Atresia and Agenesis

Urethral atresia and agenesis must be included in the differential diagnosis of renal anomalies and bilateral hydronephrosis diagnosed in utero. Unfortunately, these lesions are not compatible with renal development unless there is some other egress for the urine to escape the bladder, such as a patent urachus or an urorectal communication. Management will depend on the specific anomaly and the amount of renal function salvaged by alternative urinary drainage. An association between urethral atresia and prune-belly syndrome in females has been recognised, but few reports discuss the outcome of treatment in these gravely ill infants. Most of these children will come to renal transplants due to severe renal damage in the neonatal period. In males, progressive catheter dilation has been used reasonably and would be similarly effective in females (PADUA-progressive augmentation by dilating the urethra anterior). It is still unclear if this would offer a long-term solution.

Urethral Duplications

It is a rare set of urethral anomalies. Considering the many different anatomic variants, no common embryological pathway can explain all the variants of urethral duplication. Johnson suggested that faulty fusion of the genital ridge and urethral fold could result in two separate channels, and Lowsley proposed persistence of the urogenital plate during infoldings of the genital ridge as an explanation. Urethral duplication can occur with complete duplication of the phallus or urinary bladder as a more severe abnormality. There are two types of duplication, either sagittal or collateral. Most duplications occur in the sagittal plane with a single phallus. When one is found above the other in this setting, the dominant urethra exits in a hypospadiac position and the accessory urethra in the orthotopic position. Many of the nondominant dorsal urethras end blindly short of the bladder. If, however, they do reach the bladder, the child is often incontinent from the accessory channel. In the collateral form, the duplicate urethras run side by side. Complete duplication of the bladder and urethra is rare and particularly in females.

Figure 4 Cystogram study showing Y-Urethral Duplication with an arrows pointing to (dorsal) non dominant urethra.

In some cases, both urethras leave the bladder separately and remain separate throughout their length, whereas in other cases, the duplicate urethras unite distally to form a single channel. In the so-called 'spindle' variety, the urethra separates into two components before reuniting again more distally, whereas, in 'Y' duplications, an accessory urethra diverges from the main channel to emerge in the perianal region or the perineum. A widened symphysis pubis may be found in those cases associated with an epispadiac meatus, suggesting a relationship to the exstrophy–epispadias complex. Surgical reconstruction is dependent upon individual anatomy but nearly always entails excision of the narrower accessory urethra. Endoscopy at the time of reconstruction may occasionally be necessary to understand the lesion thoroughly. If the problem is noted because of minor splitting of the urinary stream during voiding, repair may not be necessary. Such consideration is typically only appropriate for those patients with both meatuses immediately adjacent to each other, and even those patients may benefit from a simple meatoplasty to combine both openings as one. The complexity of the repair increases as the two openings diverge, especially if the dominant ventral meatus is very proximal. In that situation, the ventral perineal urethra usually must be mobilised away from the rectum to a more orthotopic position, and the remainder of the urethra reconstructed with a variety of urethroplasty techniques. A complete prepuce is useful when present. Patients should not undergo neonatal circumcision if the anomaly is noted. Mucosal grafts may be necessary for some patients having undergone prior circumcision or surgery. They also may be necessary for some patients whose preputial skin is not adequate in length.

With the aggressive dissection needed to reconstruct the ventral urethra, exposure for excision of the accessory, dorsal urethra is usually good. That structure may also be anastomosed to the ventral urethra proximally. Passerine-Glazel and colleagues have described gradual serial dilation of the dorsal urethra to render it useful for voiding. We prefer mobilisation and reconstruction of the dominant urethra in most cases.

Meatal Stenosis

Meatal stenosis arises most frequently in circumcised boys and is caused by diaper dermatitis. The presenting symptom is usually a decreased or deflected stream. Meatotomy and meatoplasty are reliable methods of management.

Anterior Urethral Stricture

Strictures of the anterior urethra are often idiopathic (perhaps congenital) or traumatic in origin. However, strictures of post-hypospadias repair also occur with some frequency in the anterior urethra; as a result, either of the repair itself or the catheter used as a urethral stent. Strictures of the anterior urethra usually produce symptoms of irritation (hematuria, dysuria, wetting) or obstruction (straining to void, retention). They are best diagnosed with radiographic imaging of the urethra or endoscopy. Uroflowmetry may reveal an obstructive flow pattern, but the flow rate may be normal despite the presence of a stricture; therefore, uroflowmetry cannot be relied upon to rule out a stricture. Direct vision internal urethrotomy is adequate in only half of the cases but is probably not harmful if used only once. Dilation does not seem to be an appropriate treatment, as it needs repeat sessions many times over. End-to-end urethral anastomosis after excision of the stricture is the most effective treatment when it is anatomically feasible, even for post-hypospadias strictures. When urethral anastomosis is not feasible, a patch graft of buccal mucosa or skin is usually successful. PDS is best avoided as a suture material in urethral repair.

Urethral Polyps

Urethral polyps are another unusual anomaly of the male urethra. They may be congenital but have also been reported in adults, suggesting that they can be acquired or slowly grow until large enough to cause symptoms. These fibro-endothelial lesions commonly arise from the verumontanum and are typically covered with transitional epithelium over a fibromuscular core. Small polyps are usually discovered incidentally during endoscopy for some unrelated purpose. In contrast, the more extensive lesions, with a polypoid head floating freely on an extended stalk, tend to obtrude through the bladder neck to give rise to acute, transient episodes of urinary retention. Other symptoms are straining to void, urgency and hematuria. Frank urethral bleeding may also occur. Diagnosis is by MCU or cystourethroscopy. Voiding cystourethrography often shows a filling defect in the urethra that may vary in location. Diagnostic confirmation is made by cystoscopy. Most polyps can be excised endoscopically (transurethral excision), although, for large polyps, an open transvesical approach may be required.

Key Points

- Anterior urethral valves are the most common congenital obstructive lesion of the anterior urethra and usually present with obstructive symptoms. Transurethral incision of the valve is adequate for most patients.

- Urethral diverticulum can present either as the more common wide-mouthed form, or saccular form. Treatment is by endoscopic incision or resection of the obstructing lip or, rarely, by an open perineal approach excising a large diverticulum.

- Megalourethra It is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by abnormal dilatation of the penile urethra without a structural obstruction. Voiding cystourethrography and renal ultrasonography are performed to establish the diagnosis and evaluate the upper tracts. Treatment centers on reconstructing the urethra and corpus spongiosum using standard principles of hypospadias repair.

- Syringocoele is a rare cystic dilatation of the distal portion of Cowper’s gland ducts. For all patients, early diagnosis and prompt treatment are vital. Endoscopic management uses various techniques to treat syringocoeles, namely Bugbee electrode, scissors, hooked urethral catheter, catheterization, and Holmium: YAG Laser.

- Urethral atresia and agenesis must be included in the differential diagnosis of renal anomalies and bilateral hydronephrosis diagnosed in utero. Management will depend on the specific anomaly and the amount of renal function salvaged by alternative urinary drainage. In males, progressive catheter dilation has been used reasonably and would be similarly effective in females (PADUA-progressive augmentation by dilating the urethra anterior).

- Urethral duplication is a rare spectrum of urethral anomalies. The complexity of the repair increases as the two openings diverge, especially if the dominant ventral meatus is very proximal.

- Meatal stenosis arises most frequently in circumcised boys and is caused by diaper dermatitis. Meatotomy and meatoplasty are reliable methods of management.

- Anterior urethral strictures of the anterior urethra are often idiopathic (perhaps congenital) or traumatic in origin. End-to-end urethral anastomosis after excision of the stricture is the most effective treatment when it is anatomically feasible, even for post-hypospadias strictures.

- Urethral polyps are an unusual anomaly of the male urethra. These fibro-endothelial lesions commonly arise from the verumontanum. Diagnosis is by MCU or cystourethroscopy. Most polyps can be excised endoscopically (transurethral excision), although, for large polyps, an open transvesical approach may be required.

References

- Antón-Juanilla M, Lozano-Ortega JL, Galbarriatu-Gutiérrez A. A Urresola-Olabarrieta, Anterior urethral trauma in childhood: presentation of two cases. Cir Pediatr 2020; 1;33(4):200-203.

- Ansari MS, Yadav P, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Shekar PA. Etiology, and characteristics of pediatric urethral strictures in a developing country in the 21st century. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15: 403.e1–403.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.020.

- Vetterlein MW, Weisbach L, Reichardt S, Fisch M. Anterior Urethral Strictures in Children: Disease Etiology and Comparative Effectiveness of Endoscopic Treatment vs Open Surgical Reconstruction. Pediatr 2019. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2019.00005.

- Kaplan GW, Brock JW, Fisch M, Koraitim MM, Snyder HM. SIU/ICUD Consultation on Urethral Strictures: Urethral Strictures in Children. Urology 2014; 83. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.09.010.

- Perlman S, Borovitz Y, Ben-Meir D, Hazan Y, Bardin RNR, Brusilov M, et al.. Prenatal diagnosis and postnatal outcome of anterior urethral anomalies. 2020; 40 (2): 191–196. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5582.

- Thomas D, Duffy P, Rickwood A. Essentials of Paediatric Urology. 2008: 117–120. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.t01-1-03073_1.x.

- Gillenwater J, Howards S, Grayhack J, Mitchell M. Adult and Pediatric Urology ". 4th ed., USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Publishers; 2002, DOI: 10.1001/jama.1991.03460240115044.

- Stringer M, Oldham K, Mouriquand P. Pediatric Surgery and Urology: long – term outcomes". 2nd ed., USA: Cambridge University Press; 2006, DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)00082-3.

- Berrocal T, López-Pereira P, Arjonilla A, Gutiérrez J. Anomalies of the distal ureter, bladder, and urethra in children: embryologic, radiologic and pathologic features". Radiographics 2002. DOI: 10.1148/radiographics.22.5.g02se101139.

- Alonso AR, Outeda EC, Blanco AG, Martín CB, Franco JL, Pérez MAC, et al.. Duplicidad de uretra masculina. Actas Urológicas Españolas 2002; 26 (1): 69–73.

最近更新时间: 2023-05-01 08:41