52: Trauma Renal

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 6 minutos para ler.

Introdução

As lesões renais são consideradas uma das lesões do trato urinário mais comuns encontradas tanto em traumas contusos quanto penetrantes. A maioria das lesões é contusa, com menos de 10% penetrantes. As crianças apresentam maior risco de lesões renais contusas do que os adultos devido à menor quantidade de gordura perirrenal de suporte, e as costelas torácicas são mais flexíveis, o que permite que a força do trauma seja transmitida aos órgãos sólidos.

O trauma renal raramente ocorre como lesão isolada e é mais comumente associado a outros órgãos sólidos ou como parte de um politrauma. O trauma renal é dividido em 5 graus de acordo com sua gravidade, sendo que a maioria das lesões é de baixo grau.

Anatomia

É essencial compreender a anatomia do rim ao diagnosticar, classificar e manejar a lesão renal. Cada rim está localizado dentro da fáscia de Gerota, que circunda a loja renal; o espaço é preenchido por gordura perirrenal. Essa gordura atua como uma almofada protetora do rim e é menos abundante em crianças.

Composição do hilo renal de anterior para posterior: observa-se a veia renal como a mais anterior, seguida pela artéria renal, e o ureter é a estrutura mais posterior.

A veia renal direita é geralmente mais curta devido à sua proximidade com a veia cava inferior. As veias gonadais e suprarrenais drenam diretamente para a veia cava inferior no lado direito. Em contraste, à esquerda, a veia renal é geralmente mais longa e recebe as veias gonadais e suprarrenais do lado esquerdo.

Cada artéria renal origina-se diretamente da aorta e divide-se em cinco ramos: apical, superior, médio, inferior e posterior. Ocasionalmente, ramos acessórios originam-se diretamente da aorta.

Sinais sugestivos de trauma renal:

- Hematúria

- Equimose no flanco

- Lesão penetrante na região

- Costelas fraturadas (especialmente as inferiores)

- Massa abdominal

- Dor abdominal à palpação

O conceito de “hematúria significativa” após trauma é debatido em crianças.1 Enquanto alguns autores consideram um ponto de corte de >5 hemácias/HPF; outros defendem >50 hemácias/HPF. A hematúria isoladamente, porém, não é um marcador confiável de lesão renal. Além disso, o grau de** hematúria não se correlaciona com o grau de lesão**.

Com isso em mente, outros recomendam investigar qualquer hematúria (microscópica ou macroscópica) em qualquer criança com trauma abdominal contuso associado a um mecanismo de desaceleração (MVC, atropelamento, queda de altura).1

Exames Diagnósticos

Diante da suspeita de lesão renal, a ultrassonografia é a ferramenta inicial para o manejo. Como mencionado anteriormente, muitas lesões renais ocorrem no contexto de trauma abdominal contuso para os quais os protocolos atuais incluem como exame inicial o ultrassom FAST ,2,3 Esse ultrassom fornecerá a imagem inicial de que o rim possivelmente está sendo afetado pelo evento traumático.

Uma vez diagnosticado o trauma renal, devem ser realizados exames mais específicos para avaliar a extensão do comprometimento do rim. Entre o arsenal disponível ao médico, os seguintes podem ajudar a determinar tal extensão.

- US (Ultrassom): o US com Doppler pode ser utilizado naqueles com trauma muito leve e menor suspeita de lesão significativa, mas não consegue distinguir urina extravasada de sangue e não consegue avaliar com precisão o pedículo vascular.

- IVP (Pielograma Intravenoso) foi amplamente utilizado no passado e é usado atualmente quando não há Tomografia Computadorizada disponível. Pode ser realizado tanto na sala de trauma quanto no centro cirúrgico. Administra-se um contraste intravenoso de 2 mL/kg, e uma radiografia será feita após 10 minutos. É útil para avaliar a funcionalidade dos rins e a presença de qualquer extravasamento.

-

CT com contraste IV é o padrão-ouro atual: É adequado para avaliar a anatomia e a funcionalidade dos rins e do sistema renovascular de maneira eficiente em termos de tempo.

- Idealmente, uma CT "em quatro fases" com contraste IV obtém imagens das fases arterial, nefrográfica e pielográfica; no entanto, isso raramente é feito devido ao aumento da radiação associado a quatro aquisições.

- A CT padrão obtém a fase arterial e a fase cortical precoce… o que pode deixar de identificar algumas lesões parenquimatosas ou do sistema coletor.1

- Os achados da CT por si só NÃO determinam a conduta.4

- Angiografia ou urografia IV intraoperatória também são ferramentas de imagem em algumas situações.

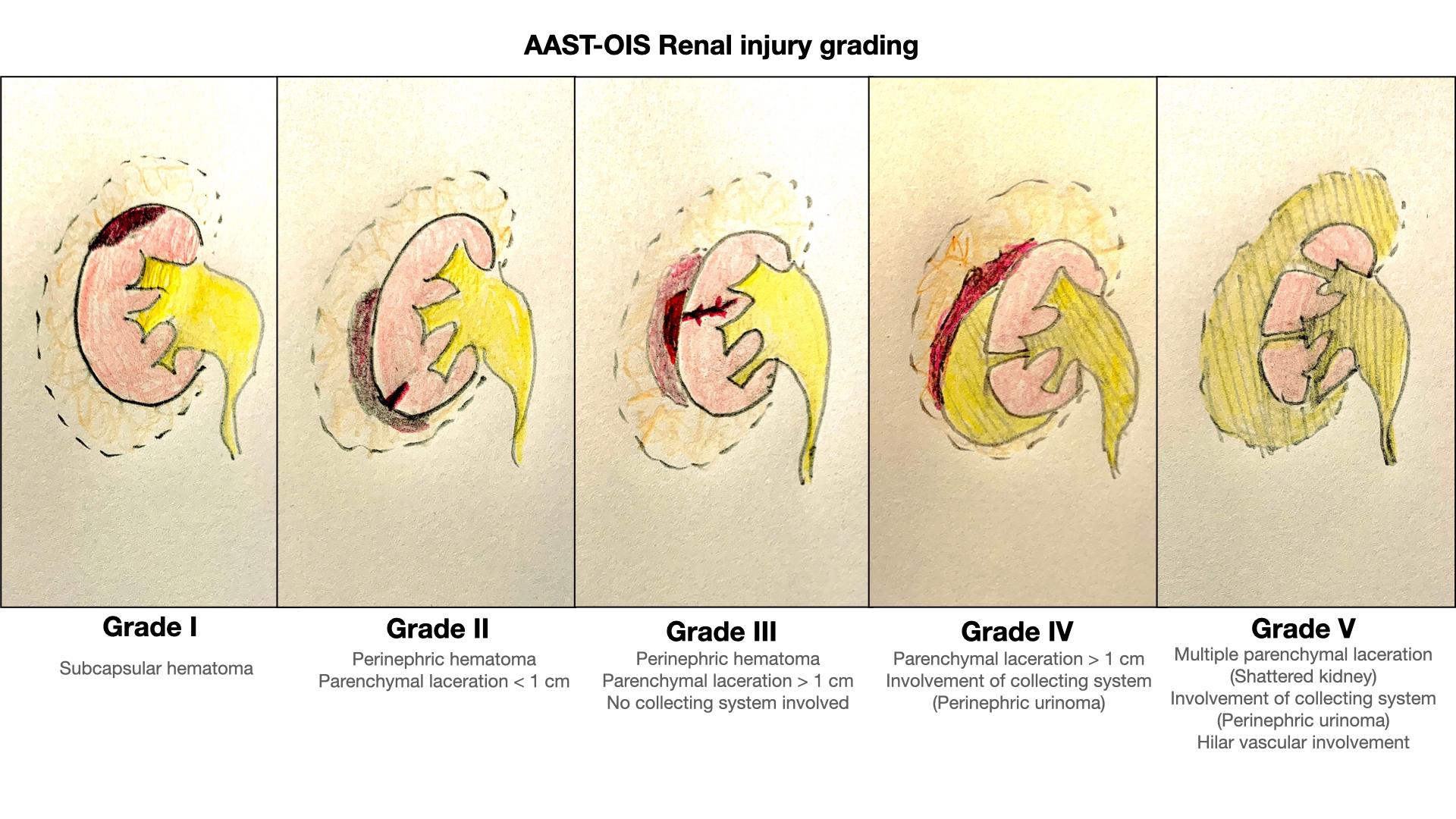

Classificação

A Escala de Lesão de Órgãos da American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST-OIS) é o sistema de classificação mais comum utilizado para lesões de órgãos sólidos, incluindo o rim.5 O sistema de classificação baseia-se na tomografia computadorizada (TC) e nos achados operatórios. Este sistema de classificação é adaptado da população adulta e ainda é utilizado no trauma pediátrico. É dividido em 5 graus: os graus 1–2 são considerados de baixo grau, enquanto 4–5 são de alto grau.

- Grau I – Contusão ou hematoma subcapsular não expansivo

- Grau II – Hematoma perinéfrico com laceração parenquimatosa < 1cm de profundidade

- Grau III – Como no Grau II, com laceração >1cm de profundidade. Sem envolvimento do sistema coletor.

- Grau IV – Laceração envolvendo o sistema coletor (urinoma perinéfrico)

- Grau V – Laceração parenquimatosa envolvendo o sistema coletor (rim estilhaçado) e/ou laceração da veia/artéria renal principal ou avulsão da artéria principal ou trombose da veia renal.

Figura 1 Sistema de classificação do trauma renal AAST-OIS.

Possíveis Complicações

- Extravasamento urinário (complicação mais comum, particularmente nos graus IV e V)

- Urinoma

- Pode apresentar-se de forma aguda ou semanas-meses depois

- Os sinais habituais são dor, febre, íleo e massa palpável

- Hemorragia secundária

- Hemorragia tardia, que ocorre em 13–25% das lesões Grau III–V

- Geralmente observada nas primeiras 2–3 semanas após o trauma

- Abscesso perinéfrico (raro)

- Formação de fístula AV (rara e exclusivamente por ferimentos por arma branca)

- Pseudoaneurisma

- Divertículos caliciais

- Função renal comprometida

- Hipertensão

Manejo

O primeiro determinante para o manejo é o estado hemodinâmico. Os pacientes estáveis podem prosseguir com a investigação completa visando a um possível manejo conservador (não operatório). Pacientes hemodinamicamente instáveis que não respondem à ressuscitação volêmica devem ser submetidos a manejo operatório urgente.

Em uma criança alerta e comunicativa com sintomas mínimos e sem achados físicos preocupantes, com <50 hemácias por campo de grande aumento, pode ser razoável optar por observação ou por ultrassonografia de triagem com Doppler, em vez de realizar uma TC apenas para avaliação dos rins.1

Uma vez diagnosticada a lesão renal secundária ao trauma, recomenda-se estabelecer drenagem urinária completa a baixa pressão. Um cateter transuretral simples na bexiga, apenas como medida inicial, é o mais simples e eficaz (e, por vezes, o único necessário).

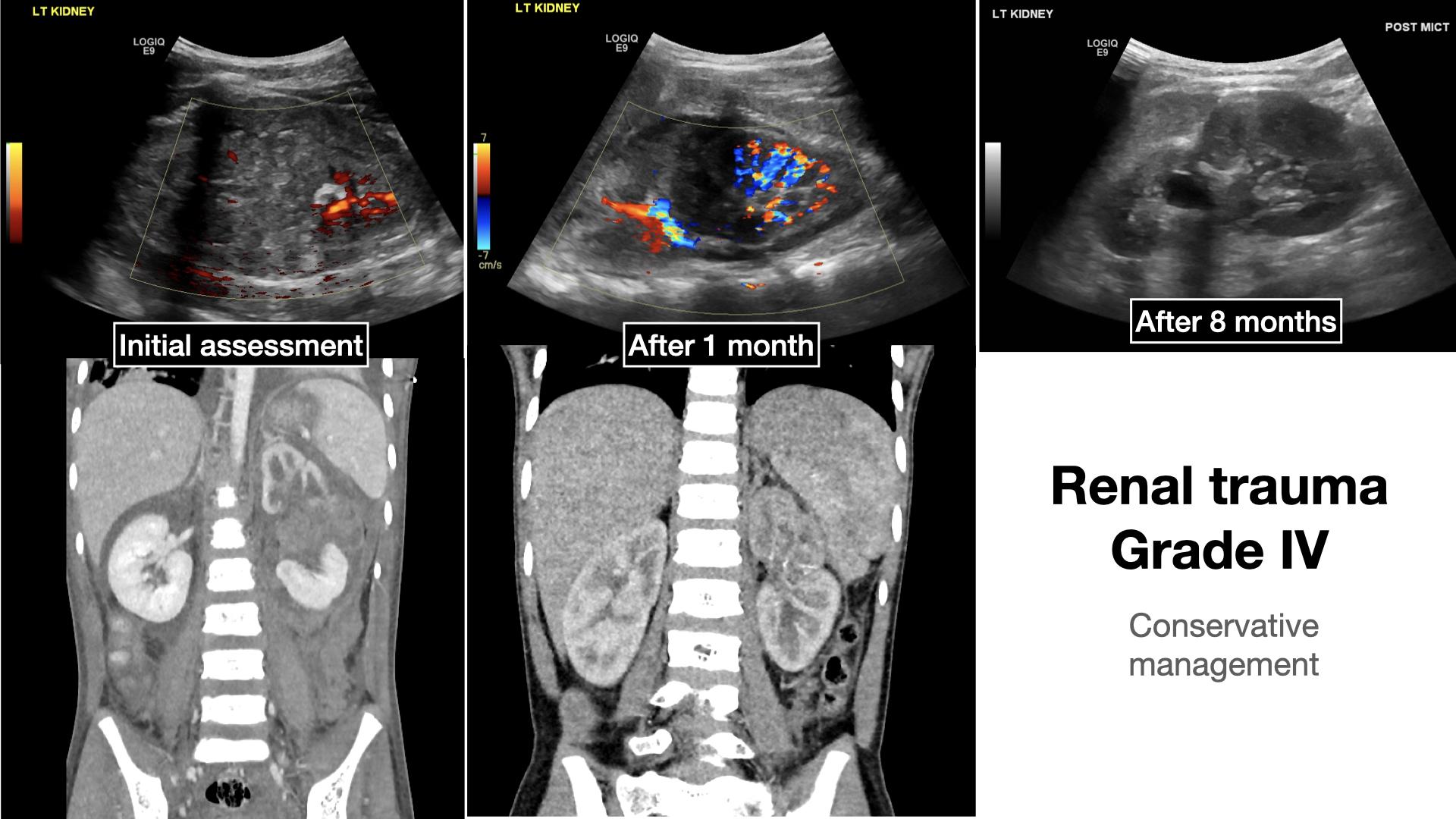

De modo geral, o trauma renal em crianças é manejado de forma conservadora, mesmo em lesões de grau mais elevado.1,4,6 Especificamente, todas as lesões de Grau I–III podem ser manejadas de forma não operatória.7 Há evidências de que os Graus IV e V também podem ser manejados de forma conservadora.4 Essas lesões de grau mais elevado exigem uma abordagem cuidadosa e personalizada para cada indivíduo.1 Isso é particularmente relevante em pacientes pediátricos, nos quais as lesões de Grau IV são uma heterogênea população.3

Figura 2 Exemplo de paciente com trauma renal Grau IV na apresentação inicial, após 1 mês e após 8 meses.

Deve-se sempre ter em mente que o sistema de classificação da American Association for the Surgery of Trauma não é perfeito e gera controvérsias.6 A razão é que esse sistema de classificação é baseado predominantemente na população adulta e pode não refletir adequadamente a população pediátrica.6 Alguns ainda subdividem o Grau IV por esse motivo.

A cirurgia é recomendada para:1

- Pacientes hemodinamicamente INSTÁVEIS

- Aqueles com lesões intra-abdominais PENETRANTES graves.

Pode ser necessária cirurgia ou radiologia intervencionista para:1

- Extravasamento urinário maciço nos graus IV–V

- Tecido inviável extenso (>20%)

- Lesão arterial

- Estadiamento incompleto

Independentemente da classificação inicial, se for instituída a conduta expectante, a monitorização contínua do paciente é recomendada para avaliar se pode haver lesão renal tardia. Qualquer alteração nos sinais vitais e/ou início recente de hematúria devem ser prontamente reavaliados por meio de exames de imagem.

Pontos-chave

- Não ignore a hematúria! Nem todos precisam de uma tomografia computadorizada (TC), de qualquer maneira!

- Conheça as limitações do seu exame de imagem! Você não pode ver o que não examina por imagem

- A menos que haja instabilidade hemodinâmica, geralmente todos os traumas podem ser manejados de forma não operatória

- Avalie e reavalie seu paciente, o quadro clínico pode mudar

Referências

- Fernández-Ibieta M. Renal Trauma in Pediatrics: A Current Review. Urology 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.030.

- Ollerton JE, Sugrue M, Balogh Z, D’Amours SK, Giles A, Wyllie P. Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma. J Trauma 2006; 60 (4): 785–791. DOI: 10.1017/cbo9780511544811.052.

- Root JM, Abo A. Cohen J. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Evaluation of Severe Renal Trauma in an Adolescent. Pediatr Emerg Care 2018; 34: 286–287. DOI: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001406.

- LeeVan E, Zmora O, Cazzulino F, Burke RV, Zagory J, Upperman JS. Management of pediatric blunt renal trauma: A systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016. DOI: 10.1097/ta.0000000000000950.

- Ballon-Landa E, Raheem OA, Fuller TW, Kobayashi L, Buckley JC. Renal Trauma Classification and Management: Validating the Revised Renal Injury Grading Scale. J Urol 2019; 202 (5): 994–1000. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000000358.

- Murphy GP, Gaither TW, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Baradaran N, Copp HL, et al.. Management of Pediatric Grade IV Renal Trauma. Curr Urol Rep 2017; 18: 23. DOI: 10.1007/s11934-017-0665-z.

- Bartley JM, Santucci RA. Computed tomography findings in patients with pediatric blunt renal trauma in whom expectant (nonoperative) management failed. Urology 2012; 80 (6): 1338–1343. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.07.077.

Ultima atualização: 2025-09-21 13:35