22: Extrofia cloacal

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 33 minutos para ler.

Introdução

Extrofia cloacal (CE), comumente referida como o complexo onfalocele, extrofia da bexiga, ânus imperfurado e anomalias da coluna vertebral (OEIS), é a manifestação menos comum do complexo extrofia-epispádia (EEC), porém representa o maior desvio em relação à anatomia e ao desenvolvimento típicos. Por se tratar de um defeito multissistêmico, requer uma abordagem multidisciplinar dedicada para alcançar desfechos ideais para os pacientes e suas famílias. Este capítulo apresenta uma revisão da extrofia cloacal sob uma ótica moderna, bem como perspectivas futuras para a compreensão dessa condição de grande impacto.

Embriologia

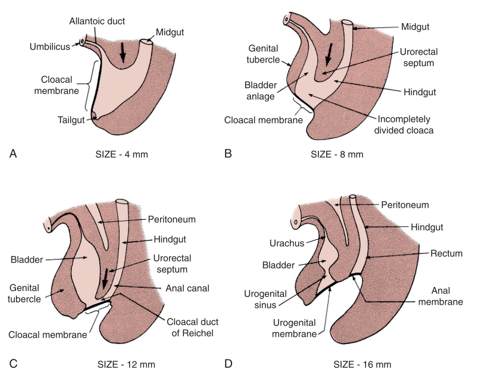

A teoria predominante por trás do EEC é a falha do crescimento mesodérmico em reforçar a membrana cloacal.1 A membrana cloacal é uma camada bilaminar de tecido ectodérmico e endodérmico localizada no aspecto caudal do disco germinativo da parede abdominal infraumbilical em desenvolvimento. No desenvolvimento normal, durante as 4a e 5a semanas de gestação, o crescimento mesenquimal entre essas camadas forma os músculos abdominais inferiores e a pelve óssea. A contínua descida caudal desse septo uroretal resulta em fusão com a membrana cloacal e, em última análise, na separação da cloaca em bexiga anteriormente e reto posteriormente (Figura 1).2 A perfuração da membrana cloacal geralmente ocorre após a fusão com o septo uroretal por volta da 6a semana de desenvolvimento, formando orifícios urogenital e anal separados. Os tubérculos genitais pareados que dão origem ao falo, então migram medialmente e fundem-se na linha média.3

Figura 1 Desenvolvimento da membrana cloacal, do seio urogenital e das aberturas anais. Proliferação mesenquimal com descida caudal do septo uroretal e perfuração da membrana cloacal, resultando nas cavidades urogenital e anal.

A falta de reforço mesenquimal e o consequente hiperdesenvolvimento da membrana cloacal acarretam risco de ruptura prematura da membrana cloacal. O momento e o grau em que ocorre a ruptura prematura dessa membrana determinam o espectro de condições observadas no EEC; CE é o defeito que se forma mais precocemente.

Epidemiologia

A incidência de CE é de aproximadamente 1 em 200.000–400.000 nascidos vivos4,5 Historicamente, na CE, há uma predominância do sexo masculino em relação ao feminino de 2:1, embora algumas séries a coloquem mais próxima de 1:1.6,7,8 Com a melhoria das modalidades de imagem e do diagnóstico pré-natal, contudo, o número de nascidos vivos com CE diminuiu de forma acentuada, uma vez que as gestações são interrompidas eletivamente em 23% dos casos e até 50% das gestações abortam espontaneamente.9

A maioria dos casos parece esporádica; no entanto, análises genéticas identificaram possíveis fatores causais. Thauvin-Robinet et al descreveram uma translocação desequilibrada entre o braço longo do cromossomo 9 e o cromossomo Y, resultando em uma deleção 9q34.1-qter como possível causa, ao passo que mutações em um grupo de genes homeobox, incluindo HLXB9 e a família HOX, que impactam o desenvolvimento mesodérmico, foram implicadas por outros.10

Além do histórico familiar, outros fatores de risco específicos de CE têm sido implicados. Em uma análise clínica e molecular de 232 famílias, a idade parental avançada surgiu como um possível fator de risco, com idade média materna de 34 anos e idade média paterna de 32 anos (em comparação com 26 e 27 anos com base nos dados do censo de 2010, respectivamente). Curiosamente, 49% das extrofias nasceram de primeiras gestações, o que também pode reforçar a idade parental avançada.10 Influências hormonais também podem desempenhar um papel, pois Wood e colegas identificaram um aumento de 10 vezes nos nascimentos com extrofia em mães que receberam grandes doses de progesterona no início do primeiro trimestre.11 Nesse mesmo estudo, também foram relatadas associações com técnicas de reprodução assistida, uma vez que crianças concebidas por fertilização in vitro (FIV) apresentaram um aumento de 7,5 vezes na ocorrência de extrofia.

Atualmente, o fator ambiental mais estreitamente associado à extrofia cloacal é a exposição materna ao tabaco, especificamente a exposição materna ao tabagismo no período periconcepcional e o tabagismo materno durante o primeiro trimestre.12 Em conjunto, emergem dois pontos críticos no aconselhamento: 1) aconselhamento apropriado quanto à otimização dos períodos periconcepcional e do primeiro trimestre – durante o período de organogênese e 2) a compreensão das mudanças nas visões da sociedade em relação ao planejamento familiar (com pais de primeira viagem em idade mais avançada) e a potencial necessidade de tecnologias de reprodução assistida.

Patogénese e Anomalias Associadas

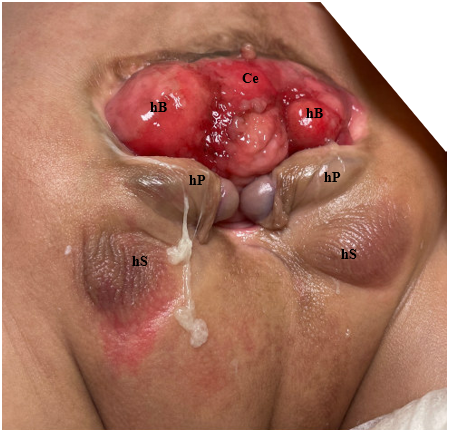

A complexidade em determinar as causas multifatoriais subjacentes à CE é demonstrada pela variedade de defeitos observados nesse fenótipo (Tabela 1). Como a CE é o resultado de eventos do desenvolvimento precoce, ela se apresenta com maior número de anomalias, de grau mais grave, e representa a extremidade mais desafiadora do espectro extrofia-epispádia. A expressão fenotípica clássica da CE envolve uma faixa de ceco extrofiado ladeada por duas metades de bexiga extrofiadas, frequentemente acompanhadas por um segmento ileal prolapsado, resultando na deformidade em “tromba de elefante” (Figura 2). Além disso, o intestino posterior é encurtado e frequentemente termina em fundo cego, resultando em ânus imperfurado. Como os tubérculos genitais não se fundem na linha média, observam-se duas metades fálicas em ambos os lados de uma diástase púbica alargada (Figura 3). O defeito da parede abdominal é geralmente acompanhado por onfalocele de tamanho variável.2 Devido à natureza multissistêmica desse defeito, cada anomalia é descrita separadamente com mais detalhes.

Tabela 1 Extrofia cloacal e suas anomalias associadas.

| Gastrointestinal | Geniturinário | Sistema Nervoso Central | Musculoesquelético |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onfalocele | Agenesia renal unilateral | Medula presa | Vertebral (ausência ou defeitos de hemivértebra) |

| Ânus imperfurado, atresia anal ou estenose | Rim pélvico | Mielomeningocele | Pé torto |

| Síndrome do intestino curto | Duplicação ureteral | Subluxação do quadril | |

| Má rotação intestinal | Hidronefrose | Escassez da musculatura do assoalho pélvico anteriormente | |

| Duplicação intestinal | Criptorquidia bilateral | ||

| Hérnias inguinais | |||

| Duplicação uterina | |||

| Duplicação vaginal |

Figura 2 Paciente do sexo masculino com apresentação clássica de extrofia cloacal com segmento ileal prolapsado, criando a deformidade em “tromba de elefante”.

Figura 3 Fotografia de paciente do sexo masculino com extrofia cloacal. Observe que já foi realizada uma colostomia. Ce = ceco; hB = hemibexiga; hP = hemifalo; hS = hemiescroto.

Musculoesquelético

Pelve óssea

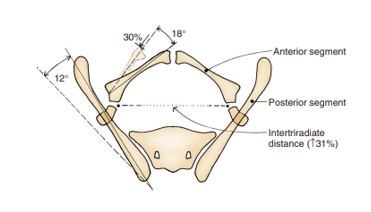

Anomalias da pelve óssea e a diástase púbica associada são o sinal distintivo da extrofia. Em 1995, Sponseller et al utilizaram tomografia computadorizada (TC) tridimensional (3D) da pelve óssea em pacientes com extrofia e elucidaram anomalias que modernizaram a nossa compreensão do alargamento característico da sínfise púbica. O mais notável é que identificaram duas amplas categorias de anomalias, denominadas anomalias rotacionais e dimensionais (Tabela 2).

Tabela 2 Anomalias da pelve óssea.

| Rotacional | Dimensional |

|---|---|

| Rotação externa da pelve posterior/asas ilíacas | Aumento da diástase púbica |

| Rotação externa do segmento pélvico anterior | Encurtamento do segmento púbico anterior (30%) |

| Rotação coronal da articulação sacroilíaca | Aumento da distância entre as cartilagens trirradiadas |

| Retroversão acetabular | |

| Convergência das asas ilíacas | |

| Retroversão femoral |

Em comparação com controles pareados por idade, Sponseller et al constataram que, na extrofia vesical clássica (CBE), a pelve posterior está rodada externamente em média 12 graus de cada lado, com a pelve anterior rodada externamente em média 18 graus. Além disso, os ramos púbicos são 30% mais curtos, o que, combinado com um acetábulo retrovertido, leva a uma diástase média de 4,8 cm na CBE (Figura 4).13 Em pacientes com CE, essas alterações são ainda mais acentuadas, com uma redução global de 43% no comprimento ósseo em toda a pelve, com uma diástase púbica média superior a 6 cm e maior probabilidade de assimetria entre os lados direito e esquerdo da pelve. Para maior clareza, diástase leve é inferior a 4 cm, diástase moderada é entre 4 e 6 cm e diástase extrema é qualquer valor > 6 cm.

Figura 4 Anomalias ósseas pélvicas observadas na extrofia vesical clássica. O segmento ósseo posterior está rotado externamente 12˚ de cada lado, mas o comprimento permanece inalterado. O segmento anterior está rotado externamente 18˚ de cada lado e encurtado em 30%. A distância entre as cartilagens trirradiadas está aumentada em 31%. Observação: as anomalias são mais graves na extrofia cloacal e a assimetria é mais comum. Usado com permissão do Brady Urological Institute.

Defeitos do Assoalho Pélvico

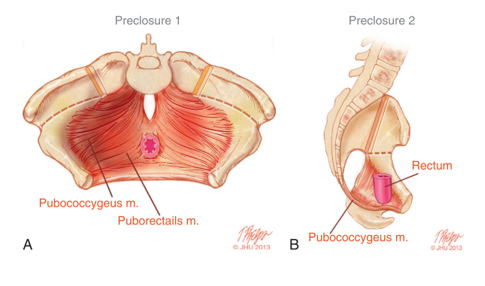

As anomalias rotacionais e dimensionais da pelve óssea impactam diretamente o desenvolvimento anômalo do assoalho pélvico. A TC 3D de crianças com extrofia revelou que os músculos levantadores do ânus estão posicionados mais posteriormente (68% posteriormente/32% anteriormente) em comparação com controles pareados por idade (52% posteriormente/48% anteriormente) (Figura 5).14 Além de estar orientado mais posteriormente, o levantador do ânus também é menos côncavo. Outra consequência das deformidades da pelve óssea manifestadas no assoalho pélvico é o músculo puborretal mais achatado em comparação à sua habitual forma cônica. A escassez de musculatura anterior do assoalho pélvico e a ausência de uma forma cônica orientam a técnica cirúrgica na reconstrução da pelve óssea e do assoalho pélvico, a qual é discutida separadamente.

Figura 5 A) Musculatura do assoalho pélvico antes do fechamento da extrofia, com as incisões de osteotomia marcadas. B) Vista lateral da anatomia do assoalho pélvico mostrando o deslocamento posterior dos músculos do assoalho pélvico atrás do reto.

Anomalias dos Membros Inferiores e da Marcha

Anomalias dos membros inferiores são consistentemente encontradas na CE. Como resultado do aumento da diástase púbica, da distância entre os quadris e da rotação externa dos acetábulos, as crianças podem compensar com rotação externa dos membros inferiores e marcha anserina. Deformidades adicionais incluem torção tibial, deformidades em equinovaro e deformidades em calcâneo.15 Apesar dessas deformidades dos membros, a amplitude de movimento nesses pacientes geralmente não é afetada e órteses corretivas, quando necessário, ajudam a corrigir a marcha ao longo do tempo. Aos 2 anos de idade, a maioria das crianças é deambulante com uso mínimo de dispositivos de assistência e poucas necessitam do uso de cadeira de rodas na infância.

Anomalias Gastrointestinais

Anomalias gastrointestinais ocorrem em algum grau em quase todos os pacientes e contribuem de forma significativa para a morbidade e para o grau de dificuldade no manejo desses pacientes, tanto no contexto perioperatório no que diz respeito à nutrição quanto no longo prazo. A onfalocele é característica dessa condição e é encontrada em 88–100% dos casos.16,17,18,19 As onfaloceles podem variar amplamente em tamanho e em seu conteúdo, contendo intestino delgado, fígado ou ambos. O fechamento imediato do defeito da onfalocele ou o seu acondicionamento dentro de um silo protetor no período neonatal é tipicamente realizado para prevenir ruptura subsequente, ao mesmo tempo em que proporciona um ambiente favorável. Em uma série de Davidoff et al que incluiu 26 pacientes com CE, todos apresentavam onfalocele. Desses pacientes, 19 (73%) tiveram fechamento primário, com o restante necessitando de redução em estágios com um silo protético temporário.16

Síndrome do intestino curto, presente em 25% dos casos, é uma causa frequente de aumento da morbidade nutricional e pode ocorrer apesar de um comprimento intestinal normal.4 Uma potencial anormalidade intrínseca de absorção intestinal reforça ainda mais a importância de uma nutrição perioperatória ótima nesses pacientes e a necessidade de preservar o máximo possível do comprimento do intestino grosso durante a reconstrução. Se não utilizado para o trânsito fecal, o remanescente do intestino posterior pode ser incorporado durante a reconstrução do trato urogenital.17 Embora existam diversas abordagens para o manejo inicial do trato intestinal, o trabalho de Sawaya et al levou a uma mudança de paradigma em 2009 com a tubularização inicial da placa cecal com confecção de colostomia terminal, pois isso reduziu drasticamente a ocorrência de síndrome do intestino curto e possibilitou futuras cirurgias de pull-through em candidatos elegíveis.20

Outras anomalias associadas do trato gastrointestinal são observadas em 46% dos casos e incluem anomalias de duplicação, gastrosquise, mal-rotação intestinal, atresia duodenal e segmentos colônicos extrofiados.16,17,21 Ânus imperfurado também é amplamente encontrado, com uma série relatando sua presença em 36 de 37 pacientes.17

Outras anomalias urológicas

Anomalias do trato urinário superior são comuns, ocorrendo em 41–66% dos pacientes.17,18 É fundamental dedicar atenção especial à identificação e à compreensão da anatomia do trato superior do paciente, pois agenesia renal unilateral, rim pélvico ou hidronefrose podem ser observados em até 48% dos casos, com múltiplas anomalias renais concomitantes em 16% dos pacientes.(missing reference) Rins em ferradura, anomalias de fusão e alterações ureterais, incluindo megaureter e duplicidade, são relatadas com menor frequência. Importante notar que as anomalias ureterais podem variar amplamente, com possível inserção ectópica do ureter no ducto deferente em homens e no útero, vagina ou trompas de Falópio em mulheres.19

Sistema Nervoso Central e Anomalias Vertebrais

Disrafismo espinal, incluindo síndrome da medula presa, mielomeningocele ou lipomielomeningocele, está presente em alguma forma em 64-100% dos pacientes, com 80% localizados na região lombar.2,18 Anomalias vertebrais além do disrafismo incluem hemivértebras e escoliose associada, observada em 40% dos pacientes, embora a escoliose não progrida na maioria dos casos.15 Devido a essa alta incidência de defeitos espinais e vertebrais, está indicada a avaliação por ressonância magnética de um recém-nascido com CE, com envolvimento da neurocirurgia conforme necessário.

O comprometimento neurológico pode, em última análise, afetar a função vesical, a continência urinária e o movimento dos membros inferiores. O grau em que cada um pode ser afetado é tão variável quanto as anomalias espinhais e vertebrais. Além disso, a microdissecção de uma pelve infantil com CE em contexto pós-mortem revelou origem e suprimento vascular anormais dos nervos autonômicos.22 Essa imprevisibilidade neurológica aumenta o desafio de ajudar esses pacientes a alcançar a continência. Defeitos da Parede Abdominal

A ruptura prematura da membrana cloacal pode resultar em um grande defeito, com ausência completa da parede abdominal inferior. Embora a apresentação desse defeito seja prontamente evidente, sutilezas exigem atenção especial. Como resultado da diástase púbica alargada e de alterações na orientação oblíqua típica do canal inguinal, hérnias inguinais são observadas em até 50% dos pacientes com CE e devem ser reparadas.23

Anomalias que afetam os órgãos reprodutivos e a genitália

No paciente do sexo masculino com CE, é típica a separação assimétrica completa do falo em duas metades, com separação concordante das metades escrotais. Os testículos podem estar localizados nos seus respectivos hemiescrotos; no entanto, frequentemente encontram-se não descendidos e associados a hérnias inguinais, exigindo correção cirúrgica. Nas pacientes do sexo feminino, os corpos clitorianos também se encontram amplamente separados.

As anomalias müllerianas também são comuns na CE, com duplicação uterina observada em 95% dos casos.19 Predomina a duplicação parcial, sendo o útero bicorno o subtipo mais comum. As anomalias vaginais variam desde agenesia, observada em 25-50% dos pacientes, até duplicação vaginal, que ocorre em até 65% dos casos.21 Nos casos de duplicação uterina ou das trompas de Falópio, deve-se priorizar a preservação para possível incorporação à reconstrução do trato urinário inferior.

Anomalias cardiovasculares e pulmonares

Raramente, CE se apresenta com defeitos cardiovasculares ou pulmonares imediatamente ameaçadores à vida. Relatos, embora raros, incluem uma variedade de anomalias maiores, incluindo duplicação aórtica e duplicação da veia cava.23 Outros descreveram Tetralogia de Fallot, atresia pulmonar, estenose da artéria pulmonar e persistência do canal arterial.24

Considerando o impacto associado dessa malformação congênita no desenvolvimento de praticamente todos os sistemas orgânicos, os cuidados a esses pacientes vulneráveis devem ser prestados em um centro com experiência nas técnicas cirúrgicas e com manejo perioperatório e pós-operatório multidisciplinar.

Avaliação e Diagnóstico

Estabelecendo o diagnóstico

Considerando a gama de defeitos associada à CE, o diagnóstico pré-natal tem-se mostrado historicamente desafiador, quando não elusivo. Diagnosticar CE com precisão e distingui-la de CBE é fundamental para orientar adequadamente as famílias, especialmente considerando que crianças com CE tendem a enfrentar mais problemas relacionados à saúde ao longo da vida. O diagnóstico pré-natal permite um planejamento que pode otimizar o manejo médico e cirúrgico pós-natal. O primeiro diagnóstico pré-natal de CE, em 1985, baseou-se em três achados-chave na ultrassonografia fetal (fUS): 1. Um grande defeito abdominal anterior infraumbilical na linha média, 2. mielomingocele lombossacra, e 3. não visualização da bexiga urinária.25 Austin e colegas refinaram ainda mais essa lista ao delinear os critérios diagnósticos como achados maiores ou menores. Observados em >50% dos casos, constituíam um critério maior e incluíam: não visualização da bexiga (91%), um grande defeito da parede anterior infraumbilical na linha média ou uma estrutura cística da parede anterior (82%), onfalocele (77%) e mielomeningocele (68%). Os critérios menores eram aqueles observados em <50% dos casos e incluíam: defeitos dos membros inferiores (23%), anomalias renais (23%), ascite (41%), arcos púbicos alargados (18%), tórax estreito (9%), hidrocefalia (9%) e artéria umbilical única (9%).26 Apesar das vastas melhorias de imagem na fUS desde que foi introduzida como ferramenta diagnóstica, estima-se que apenas 15% dos pacientes tenham sido diagnosticados no pré-natal apenas pela fUS, pois os achados podem ser identificados de forma incompleta como onfalocele isolada, CBE ou outros defeitos da linha média.

O advento da ressonância magnética fetal (fMRI) no diagnóstico pré-natal acrescentou um complemento valioso na avaliação da CE. Em comparação com a fUS, a fMRI fornece visualização anatômica superior quando a bexiga não é identificada e também pode auxiliar na avaliação da presença ou ausência de onfalocele, de defeitos espinais associados e do sexo, quando não prontamente identificados na US.27,28

Recentemente, Weiss et al identificaram achados anatômicos-chave em fUS e fMRI para avaliar a validade respectiva no diagnóstico pré-natal de CBE e CE. Entre 2001 e 2018, identificaram 21 pacientes que realizaram exames de imagem pré-natais. CBE foi o diagnóstico pós-natal em 14 e CE nos demais. 15 de 21 pacientes tinham tanto fUS quanto fMRI disponíveis para revisão, e a idade gestacional mediana para avaliação por imagem pré-natal foi de 25 semanas. Dos 16 fUS com interpretações iniciais disponíveis, o diagnóstico pré-natal original foi correto em 12 casos, resultando em uma sensibilidade de 69% do fUS. Todos os 4 casos de diagnósticos pré-natais incorretos de CE foram posteriormente classificados como CBE. Dos 18 fMRI incluídos na análise, 16 de 18 diagnósticos coincidiram (83% de sensibilidade) e os dois diagnósticos pré-natais incorretos de CE foram reclassificados como CBE. Esses erros diagnósticos foram atribuídos a uma grande placa vesical proeminente com alças intestinais dispostas posteriormente, imitando uma onfalocele contendo intestino. Concluíram que a identificação do ponto de inserção do cordão umbilical tanto no fUS quanto no fMRI era prudente para diferenciar entre CBE e CE, dados os defeitos da parede abdominal.29

As variantes da exstrofia cloacal apresentam desafios diagnósticos adicionais. Embora extremamente rara, também é possível uma variante com cobertura cutânea, como descrita em 5 de 6 pacientes em uma pequena série de casos.30

Avaliação e Manejo Pós-natal Imediato

Após o nascimento, é essencial assegurar que o paciente esteja clinicamente estável. É necessário um exame físico minucioso para confirmar as várias anomalias anatômicas que possam estar presentes (Tabela 1). Esclarecer as malformações congênitas associadas e sua gravidade auxilia no manejo clínico e cirúrgico. Como nos pacientes com CBE, os segmentos extrofiados de intestino e bexiga são mantidos úmidos, protegidos por curativo plástico.31 Uma avaliação de imagem completa, incluindo radiografias simples, ultrassonografia e RM, ajuda a determinar a gravidade dos defeitos associados e facilita o envolvimento precoce de serviços de consultoria como ortopedia pediátrica, neurocirurgia pediátrica e cirurgia geral pediátrica. Completar a equipe multidisciplinar com a contribuição e o apoio dos serviços de assistência social e nutrição é fundamental para o cuidado do lactente com CE e sua família.

Atribuição de Gênero

Uma vez que o lactente esteja clinicamente estável e que a extensão completa da condição seja compreendida, é necessária uma discussão honesta e ponderada sobre atribuição de gênero. Em muitas ocasiões, isso pode exigir consulta com a endocrinologia pediátrica, a psicologia infantil ou a psiquiatria pediátrica. Todas as decisões sobre atribuição de gênero devem ser tomadas apenas após a cariotipagem, uma discussão abrangente e o aconselhamento adequado aos pais.

Dada a expressão fenotípica típica, com ampla separação dos corpos cavernosos penianos e do escroto e tamanho fálico diminuto em meninos com CE, relatos iniciais defendiam a redesignação universal de sexo de meninos 46, XY para o sexo feminino funcional.32 Isso norteou princípios iniciais no manejo, incluindo orquiectomia bilateral juntamente com reconstrução fálica como clitóris funcional e vaginoplastia, precoce ou tardia.

Os efeitos a longo prazo dessa prática são atualmente objeto de intenso debate. Pacientes que vivem por mais tempo com essa condição oferecem um vislumbre das implicações psicossociais dessa prática e do papel potencial do genótipo e do ambiente hormonal intrauterino. Em uma coorte de 29 indivíduos do sexo masculino com CE que foram submetidos à redesignação para o gênero feminino, todos os 29 pacientes apresentaram uma mudança predominantemente masculina no desenvolvimento psicossexual, apesar de não experimentarem quaisquer picos hormonais puberais.33 Outras séries, no entanto, não demonstraram diferenças em comportamento ou questões psicossociais, embora tenha havido um caso relatado de masculinização em um paciente 46XY submetido à conversão de gênero devido a um testículo ectópico.34,35 As atitudes atuais favorecem atribuir um gênero que seja concordante com o cariótipo, quando possível. Isso foi apoiado por uma pesquisa com urologistas pediátricos na qual dois terços favoreceram uma reconstrução congruente com o gênero.36

Manejo Cirúrgico e Desfechos

Manejo inicial

O fechamento precoce da onfalocele no período neonatal é recomendado para

medida de proteção contra ruptura prematura; no entanto, isso só é realizado após as questões neurocirúrgicas serem abordadas. No momento do fechamento inicial da onfalocele, 1 de 3 abordagens geralmente é empregada para derivação intestinal e manejo do intestino posterior, incluindo confecção de ileostomia com ressecção do intestino posterior, confecção de ileostomia com fístula mucosa do intestino posterior, ou tubularização cecal com confecção de colostomia terminal.

Historicamente, a derivação intestinal inicial baseava-se em ileostomia com ressecção do intestino posterior, porém isso acarretava várias consequências indesejadas. Em primeiro lugar, isso induzia síndrome do intestino curto de forma universal e tornava menos provável a reconstrução posterior do trato gastrointestinal. Em segundo lugar, ileostomias de alto débito predispunham as crianças a maior número de hospitalizações por desidratação recorrente e distúrbios eletrolíticos.18,20 A acidose induzida secundária ao alto débito da ileostomia afeta negativamente a homeostase do cálcio e modula diretamente o eixo hormônio do crescimento-IFG-1, atenuando a liberação do hormônio do crescimento. A longo prazo, isso está associado a morbidade relacionada ao crescimento em pacientes com CE.37

Devido a isso, houve uma mudança de paradigma na derivação intestinal inicial e no manejo do intestino posterior. Em sua série de 77 pacientes, Sawaya et al constataram que o comprimento do intestino posterior variava amplamente de 2 a >20 cm, com mais da metade na faixa de 6 a 15 cm. Curiosamente, pacientes com genótipo XY tinham maior probabilidade de apresentar comprimento do intestino posterior inferior a 10 cm em comparação às suas contrapartes XX. Nesta série, apenas 10 pacientes foram submetidos à resseção do intestino posterior e somente por viabilidade duvidosa do intestino posterior ou comprimento extremamente curto. Como resultado, os autores preconizaram tubularização cecal com confecção de colostomia terminal para eliminar a síndrome do intestino curto e facilitar os procedimentos de pull-through intestinal.20 Tipicamente, a reconstrução gastrointestinal é realizada de 1 a 2 anos após a derivação fecal inicial; entretanto, se essa reconstrução for combinada com o fechamento vesical, a aproximação do púbis é fundamental para o sucesso da reconstrução da bexiga, da parede abdominal e do intestino. Tipicamente, o sucesso dessas reconstruções depende da reconstrução pélvica com osteotomias.17

Na mesma série, Sawaya et al realizaram oito procedimentos de pull-through intestinal—7 até os 5 anos de idade, variando de 2 a 12 anos—e todos os pacientes tinham intestinos posteriores preservados com pelo menos 10 cm de comprimento.20 Outros fatores a considerar ao decidir se deve realizar pull-through intestinal incluem a capacidade do paciente de produzir fezes formadas e evidência de musculatura esfincteriana anal responsiva à estimulação quando examinada sob anestesia. Em crianças que não são candidatas ao pull-through intestinal, uma estomia fecal permanente é a opção mais duradoura para o manejo a longo prazo. Vale ressaltar que, se o remanescente do intestino posterior não for incorporado ao fluxo fecal, ele deve ser preservado para futura ampliação vesical ou reconstrução vaginal.17

Se for determinado, na fase inicial do fechamento da onfalocele, que o fechamento simultâneo da bexiga e da parede abdominal não pode ser realizado de forma segura e bem-sucedida, as metades da bexiga devem ser aproximadas na linha média, convertendo o defeito em uma CBE.17 Isso permite distensão abdominal e aumento da placa vesical para um fechamento tardio subsequente. Por fim, o intestino posterior é deixado como uma fístula mucosa neste momento, se não tiver sido incorporado na reconstrução intestinal inicial.

Reconstrução urinária

Correção em Estágios Moderna

A reconstrução urinária da CE é semelhante à da CBE. A aproximação posterior das hemibexigas converte o defeito de CE para CBE e envolve a dissecção dos aspectos laterais das metades da bexiga em relação à parede abdominal, e fechamento na linha média.38 Restaurar a anatomia por meio do posicionamento da bexiga e da uretra posterior profundamente na pelve permanece um fator crucial para o sucesso da reconstrução cirúrgica. A aproximação da pelve alargada auxilia nesse objetivo, permitindo a reconstrução da parede abdominal e do trato urinário, porém, isso geralmente requer osteotomias pélvicas e fixação, como será descrito mais adiante neste capítulo.

Figura 6 Reparo moderno em estágios da extrofia. Fotografia pós-operatória do paciente visto na fotografia pré-operatória na Figura 3. Observe o posicionamento do pino de osteotomia antes da aplicação do dispositivo de fixação externa.

O grande defeito da parede abdominal encontrado na CE apresenta um desafio significativo na reconstrução da parede abdominal sem tensão (Figura 7). Não considerar a tensão no momento do fechamento pode impactar as taxas de fechamento bem-sucedido e de formação de fístula. Materiais bioprotéticos, como o Alloderm (Allergan, Branchburg, NJ), têm demonstrado grande promessa em preencher a lacuna decorrente da falta de tecido da parede abdominal, ao mesmo tempo que proporcionam um fechamento sem tensão.39 Além disso, o Alloderm tem sido utilizado como adjuvante para reduzir a fistulização penopúbica por meio da cobertura do ponto interpúbico no momento da reconstrução do trato urinário.40

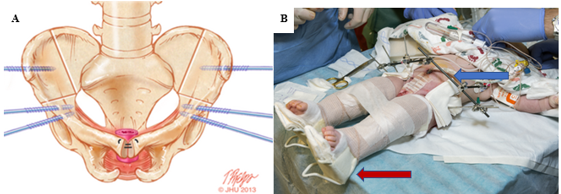

Figura 7 A, locais de osteotomia combinada anterior bilateral do osso inominado e ilíaca vertical marcados no osso com posicionamento ideal dos locais de inserção dos pinos. B, tração de Buck modificada (seta vermelha) e fixação externa (seta azul) à direita.

Para garantir congruência com o gênero atribuído, a reconstrução dos genitais externos é realizada o mais cedo possível no período pós-natal imediato. Em indivíduos com genótipo masculino, isso garantirá que sejam criados de forma congruente com seu fenótipo. Embora os efeitos psicossociais e psicossexuais em longo prazo em crianças que se submetem à redesignação de gênero sejam atualmente objeto de grande interesse, como discutido anteriormente, estudos histológicos dos testículos em indivíduos do sexo masculino que passaram por redesignação de gênero confirmam histologia normal, mesmo na presença de criptorquidia.41 Considerando o tecido peniano frequentemente reduzido e assimétrico presente, a reconstrução fálica permanece desafiadora, com resultados variados.

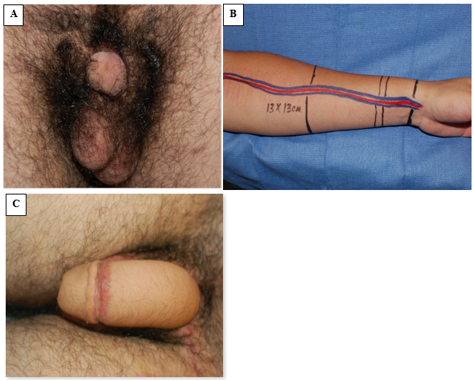

A Faloplastia surgiu como uma opção de reconstrução bem-sucedida para substituição peniana, embora isso geralmente seja adiado até a adolescência tardia (Figura 8).42 No entanto, nos casos em que a escassez de tecido exige redesignação de sexo masculino-para-feminino, a reconstrução genital inicial deve unir as metades fálicas na linha média para formar um clitóris. Quando o tecido fálico é adequado, porém, a correção da epispádia é realizada com 1 ano de idade, frequentemente utilizando a bem descrita técnica de Cantwell-Ransley.43 Em indivíduos geneticamente femininos, a reconstrução vaginal é realizada precocemente e, em indivíduos do sexo masculino com redesignação para feminino, a reconstrução tardia de uma neovagina é apropriada, sendo necessária dilatação prolongada da neovagina.44 Devido à uretra mais curta em indivíduos geneticamente femininos, a correção da epispádia isolada é tipicamente combinada com a reconstrução do colo vesical de Young-Dees-Leadbetter (BNR), monsplastia e clitoroplastia.

Figura 8 Faloplastia com retalho livre do antebraço radial. A, fotografia pré-operatória com tecido peniano discreto. B, preparação intraoperatória do tecido do retalho do antebraço e da vasculatura associada do retalho pediculado. C, fotografia pós-operatória demonstrando o resultado da faloplastia.

A Importância da Osteotomia

A osteotomia surgiu como um fator crítico para o fechamento bem-sucedido na maioria das crianças com CBE, sendo indicada em todas as crianças com CE no momento do fechamento vesical.17,44 A osteotomia corrige a ampla diástase púbica e permite o posicionamento ortotópico da bexiga e da uretra posterior tão profundamente quanto possível na pelve, além de facilitar a reconstrução da bexiga e da parede abdominal com tensão mínima. Essa redução da tensão correlaciona-se com menores taxas de deiscência e hérnias ventrais pós-operatórias. Além disso, constatou-se que a osteotomia reduz a probabilidade de complicações significativas de 89% em pacientes submetidos ao fechamento sem osteotomia para 17% em crianças submetidas ao fechamento com osteotomia.45 Isso foi confirmado em uma grande série de 80 pacientes com CE, que relatou 91% de reparos bem-sucedidos da extrofia com osteotomia realizada no momento do fechamento.46 Embora a osteotomia tenha ajudado a obter fechamento bem-sucedido, não se verificou impacto sobre a continência final em pacientes com CE.

As osteotomias combinadas bilaterais do osso inominado anterior e ilíacas verticais são o método preferido em nossa instituição e são coordenadas com o fechamento vesical em uma abordagem cunhada como Dual-Staged Pathway (DSP).47 Essa abordagem de osteotomia na posição supina proporciona o benefício adicional de não ser necessário reposicionar o paciente antes do fechamento da bexiga e da parede abdominal (Figura 7). Como se evita uma abordagem posterior, também se minimizam os riscos de lesar qualquer reparo da coluna vertebral. Além disso, as osteotomias pélvicas permitem redução pélvica gradual com fixação externa 2 a 3 semanas antes do fechamento da bexiga e da parede abdominal. Isso é frequentemente utilizado em casos de diástase púbica extremamente ampla (> 10 cm) e foi utilizado com sucesso em um paciente com diástase púbica de 16 cm.47 Em nossa instituição, a fixação externa e a tração de Buck modificada são mantidas por 6 a 8 semanas para garantir cicatrização adequada. Em nossa experiência, essa técnica de imobilização proporciona resultados excepcionais, com taxa de falha de 3,8% em fechamentos primários, em comparação com 65,7% para imobilização com gesso tipo spica.48

Reconstrução em estágio único

Outra abordagem de reparo no paciente com CE é o reparo em tempo único, ou reparo primário completo da extrofia (CPRE), popularizado por Grady e Mitchell.49 Ao contrário da abordagem em estágios de reconstrução abdominal e vesical, seguida de reparo da epispádia e de um procedimento de continência, o reparo em tempo único combina aspectos de cada etapa em um único reparo. O procedimento é semelhante ao descrito para CBE, no entanto considera o momento do fechamento em relação à onfalocele, enfatizando o adiamento do fechamento no caso de onfalocele grande ou outras condições médicas associadas. Outros concluíram que, embora o reparo em tempo único seja aplicável a um grupo selecionado de pacientes, fatores que podem contraindicar seu uso incluem placa vesical pequena, diástase púbica >6 cm, ou outras condições médicas, como disrafismo espinhal, que, mesmo na ausência de extrofia, podem requerer múltiplos procedimentos cirúrgicos .50 Em uma série limitada de 6 pacientes, Lee et al relataram fechamento bem-sucedido com reparo primário completo. Notaram, porém, o desenvolvimento de um septo vesical mediano com hidronefrose associada em duas crianças. Além disso, uma criança apresentou micção espontânea e outra foi submetida à cistoplastia de aumento (AC).51

Os proponentes dessa técnica defendem que ela pode reduzir custos, a morbidade e o trauma associados a múltiplas operações, e até estimular o crescimento precoce da bexiga. A correção do epispádias, nesse caso, é realizada por meio de desmontagem peniana, na qual a placa uretral é dissecada completamente dos corpos cavernosos. Isso permite o fechamento uretral e posiciona o colo vesical posteriormente dentro da pelve.52 Os defensores do CPRE atribuem a diminuição do número de operações para alcançar continência ao aumento da resistência da via de saída vesical em idade precoce. No entanto, muitos pacientes ainda necessitam de BNR e, notavelmente, apenas 20-56% dos pacientes submetidos ao CPRE que permanecem incontinentes alcançam continência após BNR adicional.53,54

Complicações

Tanto as reconstruções em tempo único quanto as em estágios são técnicas de reconstrução aceitáveis na CE. Embora cada abordagem tenha seus méritos, os desfechos relatados situam a taxa de falha de uma reconstrução em tempo único em 48% em comparação com 15% para uma reconstrução em estágios. Deiscência da ferida, prolapso vesical, obstrução da via de saída da bexiga e formação de uma fístula vesicocutânea devem ser considerados fechamentos malsucedidos e foram relatados em ambas as técnicas, em tempo único e em estágios.

Com qualquer abordagem cirúrgica, o fechamento vesical primário bem-sucedido é o objetivo principal. Um fechamento malsucedido é devastador para o paciente e a família e as ramificações são significativas. Pacientes que apresentam um fechamento primário malsucedido em CE estão sujeitos a mais cirurgias e maior exposição à anestesia geral. Embora um fechamento vesical malsucedido em CBE impacte negativamente a continência urinária definitiva, esse impacto especificamente sobre a continência é menos pronunciado nos pacientes com CE, pois a maioria desses pacientes requer procedimentos adicionais de continência independentemente do desfecho primário.55,56 As ramificações se estendem além das operações adicionais e incluem ônus financeiro. Goldstein et al realizaram uma análise de custos em pacientes com CE e constataram que, com um reparo primário bem-sucedido de CE, custa aproximadamente $196,000 para alcançar a continência, enquanto o custo para atingir a continência sobe para $407,000 após um fechamento vesical primário malsucedido.57

Uma grande série avaliando preditores de fechamento primário bem-sucedido na exstrofia relatou que um fechamento em estágios de CE, juntamente com o uso de osteotomia pélvica, foram preditores independentes significativos de um fechamento bem-sucedido. Além disso, após o fechamento vesical, a imobilização pós-operatória foi crucial para o sucesso.58 Por esse motivo, recomendamos o uso de fixação externa combinada com tração, como é a norma em nossa instituição. Outros métodos, como gessos pelvipodálicos, podem não proporcionar imobilização adequada e, portanto, levar a um aumento da taxa de falha da reconstrução pélvica. As complicações da osteotomia são raras e frequentemente autolimitadas, mas incluem risco aumentado de paralisias nervosas e musculares transitórias (tipicamente resolvem em até 12 semanas após a cirurgia), união ilíaca tardia e infecção ou inflamação superficial no sítio dos pinos.59 Na experiência da instituição dos autores, embora a osteotomia pélvica com imobilização pós-operatória possa prolongar o tempo de internação hospitalar, a redução drástica na taxa de falhas é considerada vantajosa pelos pacientes e profissionais de saúde.

Evidências emergentes sugerem que o momento do fechamento inicial impacta as taxas de sucesso. Em 2014, Shah e colegas relataram desfechos em 60 pacientes com CE e constataram que um aumento de 1 cm na diástase pré-fechamento resultou em um aumento de 2,64 na razão de chances de falha do fechamento inicial. A realização subsequente de osteotomia e o adiamento do fechamento, permitindo que o fixador externo diminuísse a diástase, aumentaram o sucesso do fechamento. Curiosamente, 77% dos pacientes com fechamento malsucedido foram submetidos a fechamento na primeira semana de vida, em comparação com 26% dos pacientes submetidos a fechamento estadiado. Além disso, apenas 31% dos pacientes no grupo de fechamento malsucedido foram submetidos a osteotomia durante o fechamento inicial, em comparação com 82% dos pacientes do grupo de fechamento estadiado. Outras estratégias protetoras contra falha incluem adiar o fechamento vesical inicial até após o fechamento da onfalocele.60 Por fim, 92% dos pacientes com refechamento bem-sucedido foram submetidos a osteotomia.47 Esses resultados, demonstrando maior sucesso no reparo primário adiado, foram corroborados por outra série que demonstrou uma porcentagem mais alta de falhas no fechamento vesical primário em pacientes submetidos a fechamento nos primeiros 30 dias de vida, em comparação com aqueles submetidos após 30 dias de idade (47,7% vs 19,3%).55

Para alcançar a continência após um fechamento primário malsucedido, deve-se realizar um fechamento vesical secundário. Semelhante aos achados relatados por Shah et al., Davis e colegas constataram que a idade em que o fechamento vesical secundário é realizado é preditiva do sucesso geral. Relataram que os pacientes com um fechamento vesical secundário bem-sucedido eram mais de um ano mais velhos do que os pacientes que falharam em um fechamento vesical secundário (idade mediana de 104 semanas vs 38 semanas).56 O fechamento secundário bem-sucedido teve um intervalo mediano de 154 semanas, em comparação com um intervalo mediano de 30 semanas nos fechamentos secundários malsucedidos. A reconstrução urinária malsucedida em crianças com extrofia é significativa, pois pode levar a um crescimento vesical atenuado e à perda do arcabouço vesical, o que pode tornar cada vez mais difícil, senão impossível, alcançar a continência.

Alcançar a continência

Devido à frequente coexistência de possíveis anomalias — placas vesicais pequenas, bexigas com baixa complacência, colo vesical amplamente pérvio (se é que está presente) e anomalias espinhais que contribuem para intestino e bexiga neurogênicos — a continência miccional é improvável. No entanto, a continência permanece o objetivo final na reconstrução da extrofia para permitir que essas crianças levem vidas mais típicas. Para tal, frequentemente são necessários procedimentos adicionais, como confirmado por Maruf et al em uma grande série que relatou que os pacientes necessitam de mediana de 2 (intervalo 1–4) procedimentos de continência urinária para alcançar um intervalo seco superior a 3 horas.61

Em uma grande série da instituição dos autores avaliando desfechos em 80 pacientes com complexo OEIS, havia dados sobre reconstrução urinária para 73 pacientes. Dos 40 pacientes continentes, 38 mantiveram a bexiga nativa, enquanto 2 tinham neobexigas de intestino delgado (bolsa de Koch). Dos 38 pacientes com bexiga nativa, 30 (79%) receberam um conduto cateterizável continente (derivação urinária continente, CUD) com apêndice (n =3) ou segmento intestinal (n = 27), e 32 (84%) também foram submetidos a cistoplastia de aumento (AC) antes de alcançar continência. Apenas 9 pacientes (24%) mantiveram uma uretra pérvia e continente.46 Em um conjunto de estudos avaliando a continência urinária em CE, a AC foi necessária em até 50% dos pacientes e houve uma taxa global de continência de 72%.62

Esses adjuvantes adicionais para continência, AC e CUD, apresentam complicações únicas, incluindo hiperprodução de muco, cálculos vesicais, colonização bacteriana crônica e pólipos epiteliais. Outros problemas de longo prazo surgem da AC, incluindo acidose metabólica crônica e, menos frequentemente, carcinoma.63,64 Com o tempo, o estoma criado para CUD pode estenosar, prolapsar, necrosar ou apresentar vazamento, requerendo revisão.64

Em indivíduos do sexo feminino genético, pode-se alcançar continência bem-sucedida após BNR de Young-Dees-Leadbetter, embora a maioria dos pacientes necessite de cateterismo intermitente limpo. Técnicas utilizadas em ambos os sexos para aumentar a capacidade vesical foram previamente descritas, mas incluem a incorporação do segmento do intestino posterior (quando disponível), dos intestinos delgado e grosso e, menos comumente, do estômago.38 Alcançar a continência é muito mais desafiador no paciente redesignado de masculino para feminino, e um estoma continente pode ser a estratégia mais vantajosa a longo prazo.17 Independentemente das técnicas empregadas, na experiência da nossa instituição, as crianças tornam-se continentes de urina com idade mediana de 11 anos.61 Em uma grande série que avaliou a continência em pacientes com extrofia cloacal, 50% (35 de 61) das crianças alcançaram continência, sendo que 30 de 35 realizavam cateterismo intermitente por meio de um estoma continente e o restante urinava ou realizava cateterismo pela uretra.65

Seguimento Sugerido

Pacientes com extrofia, suas famílias e as equipes médicas e cirúrgicas assistentes desenvolvem um vínculo especial, único na medicina. Após a reconstrução do trato urinário e da parede abdominal e a possível correção subsequente da epispádia, o foco do manejo passa a ser a proteção das vias urinárias superiores. Para isso, na instituição do autor, monitoramos qualquer evidência de refluxo com cistogramas anuais e cistoscopia, enquanto acompanhamos o crescimento vesical. Em crianças em idade escolar (pelo menos 5-7 anos), avaliamos a capacidade vesical, a urodinâmica e a capacidade da criança de participar do próprio cuidado, por meio da avaliação da destreza e da maturidade, antes da reconstrução do colo vesical.31

Conclusões

CE é uma malformação congênita multissistêmica devastadora que anteriormente predispunha crianças a morbidade significativa e até mortalidade. No entanto, grandes avanços no manejo cirúrgico e médico dessas crianças lhes permitiram levar vidas quase normais até a idade adulta. O sucesso no manejo contemporâneo advém da abordagem multidisciplinar para superar os desafios que esses pacientes enfrentam. À medida que esses pacientes continuam a viver vidas saudáveis ao longo da vida adulta, continuaremos a aprender mais com relação à qualidade de vida e às maneiras pelas quais a função global do paciente pode ser otimizada.

Pontos-chave

- O diagnóstico perinatal preciso e minucioso é crucial para organizar cuidados multidisciplinares apropriados—fUS e fMRI são modalidades úteis nesse propósito.

- O manejo pós-natal inicial deve assegurar que o paciente esteja clinicamente estável. Uma vez estável, deve-se realizar um exame físico minucioso e utilizar exames de imagem adequados para garantir o reconhecimento completo de todas as anomalias associadas.

- A reconstrução abdominal e do trato urinário só pode ocorrer após avaliação neurocirúrgica para investigar envolvimento da coluna ou do SNC e liberação.

- Qualquer remanescente do intestino posterior deve ser preservado a todo custo nessas crianças, pois pode ser utilizado em reconstrução gastrointestinal ou geniturinária.

- A separação da bexiga do trato gastrointestinal com desvio fecal concomitante é fundamental antes de reconstruções futuras. A colostomia terminal surgiu como a forma de desvio fecal de menor morbidade.

- O acompanhamento rigoroso após a reconstrução nesses pacientes é essencial para garantir a preservação da função do trato urinário superior.

Perspectivas Futuras

Pesquisas atuais buscam melhorar o aconselhamento e reduzir a morbidade associada à cirurgia por meio do desenvolvimento de melhores ferramentas preditivas para pacientes e familiares. Um melhor aconselhamento pode ser alcançado por meio de ferramentas, como aquelas que predizem a capacidade e o crescimento vesical (Sholklapper et al 2022, submetido), as quais podem ter implicações sobre cirurgias futuras e na capacidade de alcançar a continência.66 Além disso, pesquisas de ciência básica que avaliam diferenças de ultraestrutura entre bexigas com extrofia vesical e controles normais pareados por idade podem fornecer um quadro mais claro das curvas diferenciais de crescimento vesical para esses pacientes. O uso de métodos de imagem para avaliar a anatomia do assoalho pélvico como ferramenta para o planejamento cirúrgico fornece informações adicionais para a tomada de decisão intraoperatória, e espera-se que o uso dessas imagens se expanda. A longo prazo, abordar o crescente campo da urologia translacional e definir quem cuidará dessas crianças quando ingressarem na idade adulta ajudará a otimizar a assistência a esses pacientes. Por fim, a expansão da telemedicina para consultas entre centros médicos pode melhorar a comunicação em relação a essa condição rara e promover o bem-estar de pacientes e familiares por meio da redução do ônus relacionado à acessibilidade, deslocamentos e custos.

Leituras recomendadas

- Gearhart JP, Carlo HN. Exstrophy-epispadias complex. 12th ed., Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020, DOI: 10.1201/9780429194993-25.

- Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Complete Primary Repair Of Exstrophy. J Urol 1999; 65 (1): 1415–1420. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199910000-00071.

- Davis R, Stewart D, Maruf M, Lau H, Gearhart JP. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction combined with bladder closure in OEIS complex. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54 (11): 2408–2412. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.03.022.

- Tourchi A, Inouye BM, Di Carlo HN, Young E, Ko J, Gearhart JP. New advances in the pathophysiologic and radiologic basis of the exstrophy spectrum. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2014; 10 (2): 212–218.

- Kasprenski M, Michaud J, Yang Z, Maruf M, Benz K, Jayman J, et al.. Urothelial differences in the exstrophy-epispadias complex: potential implications for management. The Journal of Urology 2021; 205 (5): 1460–1465.

- Di Carlo HN, Maruf M, Massanyi EZ, Shah B, Tekes A, Gearhart JP. 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging guided pelvic floor dissection for bladder exstrophy: a single arm trial. The Journal of Urology 2019; 202 (2): 406–412.

Referências

- Muecke EC. The Role of the Cloacae Membrane in Exstrophy: The First Successful Experimental Study. J Urol 1069; 92 (6): 659–668. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)64028-x.

- Woo LL, Thomas JC, Brock JW. Cloacal exstrophy: A comprehensive review of an uncommon problem. J Pediatr Urol 2010; 6 (2): 102–111. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.09.011.

- Moore KL. Organogenetic Period: The Fourth to Eighth Weeks. In: Moore KL, Persaud TVN, editors. The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2003.

- Howell C, Caldamone A, Snyder H, Ziegler M, Duckett J. Optimal management of cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg 1983; 18 (4): 365–369. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80182-1.

- Cervellione RM, Mantovani A, Gearhart J, Bogaert G, Gobet R, Caione P, et al.. Prospective study on the incidence of bladder/cloacal exstrophy and epispadias in Europe. J Pediatr Urol 2015; 11 (6): 337.e1–337.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.03.023.

- Shapiro E, Lepor H, Jeffs RD. The Inheritance of the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. J Urol 1984; 132 (2): 308–310. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)49605-4.

- Ives E, Coffey R, Carter CO. A family study of bladder exstrophy. J Med Genet 1980; 17 (2): 139–141. DOI: 10.1136/jmg.17.2.139.

- Birth Defects Monitoring Systems IC for. Epidemiology of bladder exstrophy and epispadias: A communication from the international clearinghouse for birth defects monitoring systems. Teratology 1987; 36 (2): 221–227. DOI: 10.1002/tera.1420360210.

- Botto LD, Feldkamp ML, Amar E, Carey JC, Castilla EE, Clementi M, et al.. Acardia: Epidemiologic findings and literature review from the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2011; 157 (4): 262–273. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30318.

- Boyadjiev SA, Dodson JL, Radford CL, Ashrafi GH, Beaty TH, Mathews RI, et al.. Clinical and molecular characterization of the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: analysis of 232 families. BJU Int 2004; 94 (9): 1337–1343. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.05170.x.

- WOOD HADLEYM, TROCK BRUCEJ, GEARHART JOHNP. In Vitro Fertilization and the Cloacal-Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex: Is there an Association? J Urol 2003; 169 (4): 1512–1515. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000054984.76384.66.

- Reutter H, Boyadjiev SA, Gambhir L, Ebert A-K, Rösch WH, Stein R, et al.. Phenotype Severity in the Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex: Analysis of Genetic and Nongenetic Contributing Factors in 441 Families from North America and Europe. J Pediatr 2011; 159 (5): 825–831.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.042.

- Sponseller PD, Bisson LJ, Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD, Magid D, Fishman E. The anatomy of the pelvis in the exstrophy complex. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995; 77 (2): 177–189. DOI: 10.2106/00004623-199502000-00003.

- Stec AA, Pannu HK, Tadros YE, Sponseller PD, Fishman EK, Gearhart JP. Pelvic Floor Anatomy In Classic Bladder Exstrophy Using 3-dimensional Computerized Tomography: J Urol 2001; 166 (4): 1444–1449. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200110000-00066.

- Greene WB, Dias LS, Lindseth RE, Torch MA. Musculoskeletal problems in association with cloacal exstrophy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991; 73 (4): 551–560. DOI: 10.2106/00004623-199173040-00012.

- Davidoff AM, Hebra A, Balmer D, Templeton JM, Schnaufer L. Management of the gastrointestinal tract and nutrition in patients with cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg 1996; 31 (6): 771–773. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90129-3.

- Mathews R, Jeffs RD, Reiner WG, Docimo SG, Gearhart JP. Cloacal Exstrophy-improving The Quality Of Life. J Urol 1998; 6 (2): 2452–2456. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199812020-00017.

- McHoney M, Ransley PG, Duffy P, Wilcox DT, Spitz L. Cloacal exstrophy: Morbidity associated with abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract and spine. J Pediatr Surg 2004; 39 (8): 1209–1213. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.04.019.

- Sugar EC, Firlit CF. Management of cloacal exstrophy. Urology 2004; 32 (4): 320–322. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(88)90234-8.

- Sawaya D, Goldstein S, Seetharamaiah R, Suson K, Nabaweesi R, Colombani P, et al.. Gastrointestinal ramifications of the cloacal exstrophy complex: a 44-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45 (1): 171–176. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.10.030.

- Hurwitz RS, Manzoni GAM, Ransley PG, Stephens FD. Cloacal Exstrophy: A Report of 34 Cases. J Urol 1987; 138 (4 Part 2): 1060–1064. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)43502-6.

- Phillips TM, Salmasi AH, Stec A, Novak T, Gearhart JP, Mathew J. Re: Urological Outcomes in the Omphalocele Exstrophy Imperforate Anus Spinal Defects (OEIS) Complex: Experience with 80 Patients. J Urol 2013; 191 (4): 1118–1119. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.01.044.

- Schlegel PN, Gearhart JP. Neuroanatomy of the Pelvis in an Infant with Cloacal Exstrophy: A Detailed Microdissection with Histology. J Urol 1989; 141 (3 Part 1): 583–585. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40901-3.

- Connolly JA, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Prevalence and Repair of Inguinal Hernias in Children with Bladder Exstrophy. J Urol 1995; 154 (5): 1900–1901. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199511000-00093.

- Sadula SR, Kanhere SV, Phadke VD. Exstrophy of Cloaca Sequence (Oeis Complex) With Multiple Cardiac Malformations. Indian Journal of Case Reports 2019; 05 (04): 317–319. DOI: 10.32677/ijcr.2019.v05.i04.006.

- Meizner I, Bar-Ziv J. In utero prenatal ultrasonic diagnosis of a rare case of cloacal exstrophy. J Clin Ultrasound 1985; 13 (7): 500–502. DOI: 10.1002/jcu.1870130714.

- Austin PF, Homsy YL, Gearhart JP, Porter K, Guidi C, Madsen K, et al.. The Prenatal Diagnosis Of Cloacal Exstrophy. J Urol 1998; 160 (3.2): 1179–1181. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199809020-00061.

- Calvo-Garcia MA, Kline-Fath BM, Rubio EI, Merrow AC, Guimaraes CV, Lim F-Y. Fetal MRI of cloacal exstrophy. Pediatr Radiol 2013; 43 (5): 593–604. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-012-2571-3.

- Goto S, Suzumori N, Obayashi S, Mizutani E, Hayashi Y, Sugiura-Ogasawara M. Prenatal findings of omphalocele-exstrophy of the bladder-imperforate anus-spinal defects (OEIS) complex. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2012; 52 (3): 179–181. DOI: 10.1111/j.1741-4520.2011.00342.x.

- Weiss DA, Oliver ER, Borer JG, Kryger JV, Roth EB, Groth TW, et al.. Key anatomic findings on fetal ultrasound and MRI in the prenatal diagnosis of bladder and cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (5): 665–671. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.07.024.

- Lowentritt BH, Van Zijl PS, Frimberger D, Baird A, Lakshmanan Y, Gearhart JP. Variants Of The Exstrophy Complex: A Single Institution Experience. J Urol 2005; 173 (5): 1732–1737. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000154353.03056.5c.

- Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. The bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. 3rd ed., Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1998, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-44182-5_13.

- Tank ES, Lindenauer SM. Principles of management of exstrophy of the cloaca. Am J Surg 1970; 119 (1): 95–98. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9610(70)90018-8.

- Reiner WG, Gearhart JP. Discordant Sexual Identity in Some Genetic Males with Cloacal Exstrophy Assigned to Female Sex at Birth. N Engl J Med 2004; 350 (4): 333–341. DOI: 10.1056/nejmoa022236.

- Baker Towell DM, Towell AD. A Preliminary Investigation Into Quality of Life, Psychological Distress and Social Competence in Children With Cloacal Exstrophy. J Urol 2003; 169 (5): 1850–1853. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000062480.01456.34.

- Mirheydar H, Evason K, Coakley F, Baskin LS, DiSandro M. 46, XY female with cloacal exstrophy and masculinization at puberty. J Pediatr Urol 2009; 5 (5): 408–411. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.03.013.

- Diamond DA, Burns JP, Mitchell C, Lamb K, Kartashov AI, Retik AB. Sex assignment for newborns with ambiguous genitalia and exposure to fetal testosterone: Attitudes and practices of pediatric urologists. J Pediatr 2006; 148 (4): 445–449. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.043.

- Fullerton BS, Sparks EA, Hall AM, Chan Y-M, Duggan C, Lund DP, et al.. Growth morbidity in patients with cloacal exstrophy: a 42-year experience. J Pediatr Surg 2016; 51 (6): 1017–1021. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.02.075.

- Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. Techniques to Create Urinary Continence in the Cloacal Exstrophy Patient. J Urol 1991; 146 (2 Part 2): 616–618. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37871-0.

- Davis R, Stewart D, Maruf M, Lau H, Gearhart JP. Complex abdominal wall reconstruction combined with bladder closure in OEIS complex. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54 (11): 2408–2412. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.03.022.

- Henderson CG, North AC, Gearhart JP. The use of alloderm as an adjunct in the closure of the bladder – Cloacal exstrophy complex. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (1): 44–47. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.02.209.

- Mathews, Perlman, Marsh, Gearhart. Gonadal morphology in cloacal exstrophy: implications in gender assignment. BJU Int 1999; 84 (1): 99–100. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00148.x.

- Lumen N, Monstrey S, Selvaggi G, Ceulemans P, De Cuypere G, Van Laecke E, et al.. Phalloplasty: A Valuable Treatment for Males with Penile Insufficiency. Urology 2008; 71 (2): 272–276. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.08.066.

- Gearhart JP, Leonard MP, Burgers JK, Jeffs RD. The Cantwell-Ransley Technique for Repair of Epispadias. J Urol 1992; 148 (3 Part 1): 851–854. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36742-3.

- Gearhart JP, Carlo HN. Exstrophy-epispadias complex. 12th ed., Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020, DOI: 10.1201/9780429194993-25.

- Ben-Chaim J, Peppas DS, Sponseller PD, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Applications of Osteotomy in the Cloacal Exstrophy Patient. J Urol 1995; 154 (2.2): 865–867. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199508000-00146.

- Mathews R, Gearhart JP, Bhatnagar R, Sponseller P. Staged Pelvic Closure of Extreme Pubic Diastasis in the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. J Urol 2006; 176 (5): 2196–2198. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.07.058.

- Benz KS, Jayman J, Maruf M, Baumgartner T, Kasprenski MC, Friedlander DA, et al.. Pelvic and lower extremity immobilization for cloacal exstrophy bladder and abdominal closure in neonates and older children. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53 (11): 2160–2163. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.11.066.

- Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Complete Primary Repair Of Exstrophy. J Urol 1999; 65 (1): 1415–1420. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199910000-00071.

- Thomas JC, DeMarco RT, Pope JC, Adams MC, Brock JW. First Stage Approximation of the Exstrophic Bladder in Patients With Cloacal Exstrophy–Should This be the Initial Surgical Approach in all Patients? J Urol 2007; 178 (4s): 1632–1636. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.164.

- Lee RS, Grady R, Joyner B, Casale P, Mitchell M. Can a Complete Primary Repair Approach be Applied to Cloacal Exstrophy? J Urol 2006; 176 (6): 2643–2648. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.052.

- Mitchell ME, Bagli DJ. Complete Penile Disassembly for Epispadias Repair. J Urol 1996; 155 (1): 300–304. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199601000-00128.

- Gargollo P, Hendren WH, Diamond DA, Pennison M, Grant R, Rosoklija I, et al.. Bladder Neck Reconstruction is Often Necessary After Complete Primary Repair of Exstrophy. J Urol 2011; 185 (6s): 2563–2571. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.024.

- Schaeffer AJ, Stec AA, Purves JT, Cervellione RM, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Complete Primary Repair of Bladder Exstrophy: A Single Institution Referral Experience. J Urol 2011; 186 (3): 1041–1047. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.099.

- Friedlander DA, Di Carlo HN, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. Complications of bladder closure in cloacal exstrophy: Do osteotomy and reoperative closure factor in? J Pediatr Surg 2017; 52 (11): 1836–1841. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.12.002.

- Davis R, Sood A, Maruf M, Singh P, Kasprenski MC, DiCarlo HN, et al.. The failed bladder closure in cloacal exstrophy: Management and outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54 (11): 2416–2420. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.02.012.

- Goldstein SD, Inouye BM, Reddy S, Lue K, Young EE, Abdelwahab M, et al.. Continence in the cloacal exstrophy patient: What does it cost? J Pediatr Surg 2016; 51 (4): 622–625. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.12.003.

- Jayman J, Tourchi A, Feng Z, Trock BJ, Maruf M, Benz K, et al.. Predictors of a successful primary bladder closure in cloacal exstrophy: A multivariable analysis. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54 (3): 491–494. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.030.

- Inouye BM, Tourchi A, Di Carlo HN, Young EE, Gearhart JP. Modern Management of the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. Surg Res Pract 2014; 2014 (587064): 1–9. DOI: 10.1155/2014/587064.

- Shah BB, Di Carlo H, Goldstein SD, Pierorazio PM, Inouye BM, Massanyi EZ, et al.. Initial bladder closure of the cloacal exstrophy complex: Outcome related risk factors and keys to success. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49 (6): 1036–1040. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.01.047.

- Maruf M, Kasprenski M, Jayman J, Goldstein SD, Benz K, Baumgartner T, et al.. Achieving urinary continence in cloacal exstrophy: The surgical cost. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53 (10): 1937–1941. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.02.055.

- Mathews R. Achieving urinary continence in cloacal exstrophy. Semin Pediatr Surg 2011; 20 (2): 126–129. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2010.12.009.

- Surer I, Ferrer FA, Baker LA, Gearhart JP. Continent Urinary Diversion and the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. J Urol 2003; 169 (3): 1102–1105. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000044921.19074.d0.

- Woodhouse CRJ, North AC, Gearhart JP. Standing the test of time: long-term outcome of reconstruction of the exstrophy bladder. World J Urol 2006; 24 (3): 244–249. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-006-0053-7.

- Suson K, Novak T, Gupta A, Benson J, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. The Neuro-Orthopedic Manifestations of the Omphalocele Exstrophy Imperforate Anus Spinal Defects (OEIS) Complex. J Pediatr Urol 2010; 5 (4): S54. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.02.083.

- Di Carlo HN, Maruf M, Massanyi EZ, Shah B, Tekes A, Gearhart JP. 3-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging guided pelvic floor dissection for bladder exstrophy: a single arm trial. The Journal of Urology 2019; 202 (2): 406–412.

- Tourchi A, Inouye BM, Di Carlo HN, Young E, Ko J, Gearhart JP. New advances in the pathophysiologic and radiologic basis of the exstrophy spectrum. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2014; 10 (2): 212–218.

- Kasprenski M, Michaud J, Yang Z, Maruf M, Benz K, Jayman J, et al.. Urothelial differences in the exstrophy-epispadias complex: potential implications for management. The Journal of Urology 2021; 205 (5): 1460–1465.

Ultima atualização: 2025-09-21 13:35