2: Imaging of the Urinary Tract

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 21 minutos para ler.

Introduction

Diagnostic imaging is a powerful tool for understanding the natural history of many conditions affecting the genitourinary (GU) tract, from both an anatomic and a functional perspective. With optimal use, diagnostic imaging improves patient outcomes while minimizing patient risk. Multiple modalities are available to image the human body in detail including ultrasound (US), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), nuclear scintigraphy, and fluoroscopy/ radiography. Technological advances in these modalities are ongoing.

In the pediatric setting, the indications for diagnostic imaging depend not only upon the clinical presentation, but also the age (or level of development) of the patient. More than one imaging technique may be required to fully evaluate the anatomy and physiology of the GU tract. While the clinical presentation is paramount and will often allow for an algorithmic approach to imaging, the best approach in a teenager can differ from that in a baby or toddler.

Radiation Considerations

Over the past twenty to thirty years, clinicians and laypeople alike have become more concerned about radiation exposure from medical imaging and its potential dangers, especially in pediatric patients. Risk of future cancers may be higher in children due to several factors. First, young children are smaller than adults, leading to more kinetic energy per unit mass for the same amount of exposure. Children also have greater cell proliferation rates, increasing radiosensitivity. Finally, children have longer life expectancy from the time of the radiation exposure, allowing for radiation-induced chromosomal mutations to become clinically relevant.1

In many cases, the clinical question can be answered without the use of ionizing radiation. Care should be taken, however, to weigh the risks and benefits of a procedure. In cases of trauma, the gold standard remains a contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis.2 It should comfort the ordering clinician to know that twenty years of improvements in CT technology have allowed for doses between ten and a hundred (or more) fold lower than those at the turn of the millennium.3 On the other hand, many clinicians are not aware that a single abdominal radiograph (KUB) does not spare much radiation compared to a modern CT of the belly.4

While MRI may seem preferable to CT from a radiation standpoint, sedation for MRI is still a necessity in most children under the age of about 8 years. The risks of sedation (especially repeated sedation) for children are still unclear. Faster scanning times, virtual reality interfaces, and robust child life programs all hold promise for minimizing sedation needs.5

Questions to be asked when choosing an investigation are:

- Will this investigation answer the clinical question?

- Is there a previous investigation that would answer the current clinical question?

- Is there a safer (consider radiation or sedation need) alternative?

- What is the developmental level of my patient?

If there is any doubt, discussion with your radiologist is advisable.

Contrast in Imaging of the Urinary Tract

Iodinated Contrast Agents

Iodinated contrast is used for CT and VCUG. When ordering a procedure involving contrast, the clinician should be aware of potential risks. The first is the risk of a severe allergic or allergic-like reaction. These adverse events are highly unlikely with modern contrast agents. An estimate for the rate of allergic type reactions is 0.6%, of which most are mild and self-limiting. For severe reactions, the estimate is 0.04%. History of prior allergic type reaction to iodinated contrast is the clearest and most important risk factor for a subsequent reaction. The risk in patients with such a history should be carefully weighed against the benefit of a subsequent CT scan. Evidence remains inconclusive as to the benefits of premedication.6

The second risk that the ordering clinician should consider is the risk of contrast-induced acute kidney injury (CI-AKI), defined as a sudden deterioration in renal function that is caused by the intravascular administration of iodinated contrast. Unfortunately, the true risk of this entity is unknown even in adults. As is the case with allergic type reactions, there is one risk factor that is generally accepted, in best practice, to predispose a patient to CI-AKI; this risk factor is pre-existing renal insufficiency. No clear threshold of eGFR has been established (above which risk can be ignored). However, the American College of Radiology (ACR) recommends an eGFR cutoff of 30 mL/min/1.73 m.26

Calculation of eGFR in children requires knowledge of the patient height and serum creatinine. The approximate eGFR is then given by the bedside Schwartz equation:6

GFR (mL/min/1.73 m2) = 0.41 × height / serum creatinine

There are newer formulas that provide more accurate estimates of renal function on the basis of serum creatinine or cystatin-c, including the CKiD-U25 equations, which are age, sex, and height adjusted.7 A calculator is available here. It is important to note that dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease patients can receive iodinated contrast without risk of AKI, as they have non-functioning kidneys.

MRI Contrast Agents

For contrast enhanced MRI, a gadolinium chelate is used. Allergic reactions to these agents are even less likely than to iodinated contrast, with an approximate rate of 0.05%. Management of allergic reactions to gadolinium is the same as for iodinated contrast agents, and this will be discussed below. A risk unique to gadolinium agents is nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a disease resembling scleroderma which can lead to joint contractures and organ failure and can occasionally be fatal.6 This entity is still poorly understood, but it is fortunately quite rare. Patients with acute kidney injury, stage 4 or stage 5 chronic kidney disease, or those on dialysis may have up to a 7% risk of developing NSF with certain gadolinium agents (types I or possibly III). The use of gadolinium in such patients may still be appropriate in rare cases where the potential benefit of a contrast-enhanced MRI is very high. However, informed consent in this circumstance is good practice. Whenever possible, a lower risk gadolinium agent (group II) should be used in this population.6

Ultrasound Contrast Agents

Ultrasound contrast agents consist of a phospholipid or protein microsphere containing an echogenic inert gas. These agents transiently improve ultrasound contrast resolution and are approved for intravenous and endoluminal use. Dedicated ultrasound software is required. Ultrasound contrast agents are very safe, with severe reactions occurring in approximately 0.01% of cases. There is no known renal toxicity at approved doses.6

Management of Allergic-Type Reactions

Current recommendations by the American College of Radiology Manual on Contrast Media for management of allergic reactions advise prompt administration of epinephrine in the presence of the following:

- Severe bronchospasm

- Diffuse erythema with profound hypotension

- Laryngeal edema

- Hypotension with tachycardia

Current dosing regimen is summarized in the table below (Table 1).8

Table 1 Epinephrine dosage for contrast reactions.

| Route | Dose | Notes | Repeat | Max dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intravenous | 0.01 mg/kg | slowly into running IV infusion of fluids | Every 5-15 minutes | 1 mg |

| intramuscular | 0.01 mg/kg | Every 5-15 minutes | 1 mg | |

| Auto Injector 15–30 kg | 0.15 mg | Use IV (above) if less than 15 kg | ||

| Auto Injector > 30 kg | 0.3 mg |

ACR Appropriateness Criteria

American College of Radiology (ACR) appropriateness criteria are consensus recommendations freely available online to the clinician in search of the appropriate imaging study in various situations. The recommendations are developed by panels of experts and are frequently updated.

Table 2 ACR Appropriateness criteria renal ultrasound recommendations.

| Indication | Notes |

|---|---|

| Neonate with prenatal UTD, initial post-natal ultrasound | Ideally at least 72 hours old |

| Neonate with prenatal UTD and normal post-natal ultrasound | Follow-up 1–6 months at clinician’s discretion |

| Neonate with prenatal UTD and SFU grade 1-2 or APRPD less than 15 mm on post-natal ultrasound | Consider voiding study as complimentary investigation |

| Neonate with prenatal UTD and SFU grade 3-4 or APRPD greater than 15 mm on post-natal ultrasound | Voiding study and nuclear medicine collecting system scan also recommended |

| Atraumatic hematuria | When macroscopic or associated with proteinuria |

| Suspected urolithiasis | |

| Febrile UTI | In child under 2 months |

| Recurrent febrile UTI or poor response to antibiotics |

Imaging Modalities

Ultrasound

In children, ultrasound (US) is a workhorse modality. It is nearly always the first line of investigation in suspected renal abnormalities (trauma is the notable exception). US is cheap, non-ionizing, and is readily available. The disadvantage is that it is operator dependent. Especially when interpretation is remote, the radiologist relies heavily on the sonographer.

For the indications below, ultrasound is recommended as the initial imaging modality.8,9

Kidney Anatomy

Renal sizes for age have been well established and appropriate growth can readily be demonstrated by ultrasound. There is an approximate margin of error of plus or minus 7 mm depending on imaging planes or patient motion (with CT serving as the gold standard), meaning that comparison across several prior ultrasounds will provide a more reliable indication of renal growth (or lack thereof). Kidneys may be lobular or have prominent columns of Bertin as normal variants.

Corticomedullary differentiation is normally very conspicuous in neonates. As cortical glomeruli are physiologically pruned as the child matures, the cortex normally becomes more hypoechoic. Thus, the normal kidney in an older child or teenager will resemble the adult appearance, with near isoechogenicity of the cortex and medulla contrasting clearly with the bright renal sinus. A familiarity with the normal appearance of the kidney at different ages is essential for the pediatric radiologist and allows for the diagnosis of subtle abnormalities.

Figure 1 Normal kidney in a four month old.

Figure 2 Normal kidney in a 3 year old.

Figure 3 Normal Kidney in an 11 year old.

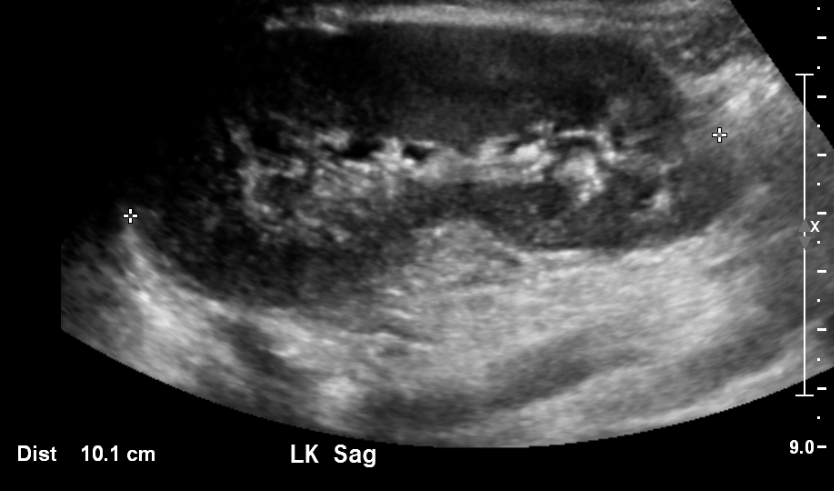

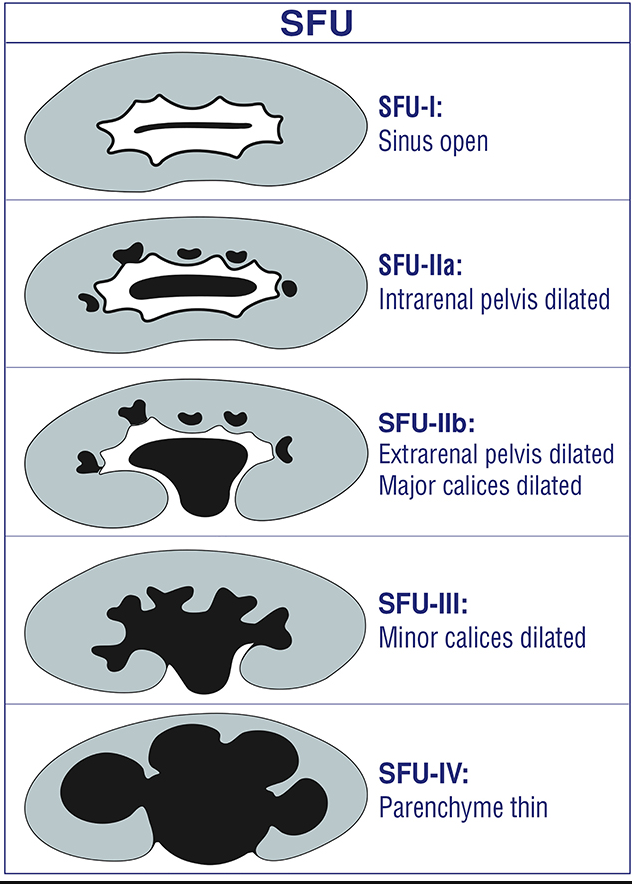

Follow Up of Prenatal Urinary Tract Dilation

This is the most common indication for a pediatric renal ultrasound in the outpatient setting. The architecture of the dilated collecting system is usually well-depicted by ultrasound and can provide clues to the etiology. Despite many efforts at standardization (beginning in 1988 and ongoing), descriptive terminology has been sadly inconsistent. This inconsistency has hampered efforts to correlate urologic outcomes with the degree of prenatal collecting system dilation. While ACR appropriateness criteria are based on the 1988 SFU classification system, most children’s hospitals have now adopted the UTD classification system. This classification system was developed in 2014. UTD introduced unified descriptive terminology for both pre and postnatal ultrasound to facilitate standardized perinatal evaluation. The clinician is well advised to become familiar with the wording within their affiliated radiology practice and encourage standardization where possible.

Figure 4 SFU grading of collecting system dilation

Figure 5 (a) Urinary tract dilation (UTD) classification shows a transverse view of mid/interpolar kidney. Green arrows indicate anterior-posterior diameter (use largest measurement). The extrarenal pelvis should not be included (gray arrows). (b) Longitudinal views of various grades within the UTD classification system. Adapted from Chow et al 2017.10

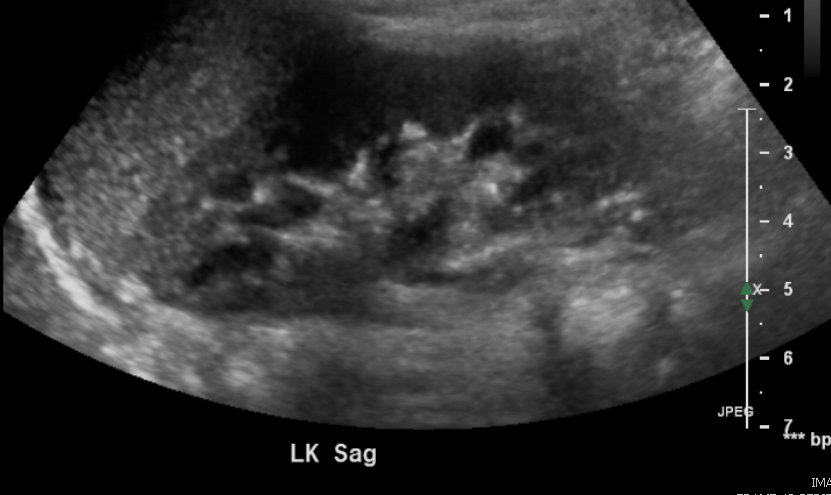

Figure 6 Duplicated collecting system in a newborn

Figure 7 Same patient as (Figure 6) at two weeks old showing more severe dilation

Figure 8 Ureteropelvic junction obstruction

Figure 9 Severe caliectasis and cortical thinning in a patient with posterior urethral valves

Screening for Tumor in Predisposing Genetic Conditions Such as Beckwith-Wiedemann or WAGR

Ultrasound can detect subtle solid masses in young children, as illustrated by the example below. Frequency of screening and age range vary according to the specific predisposing condition.11

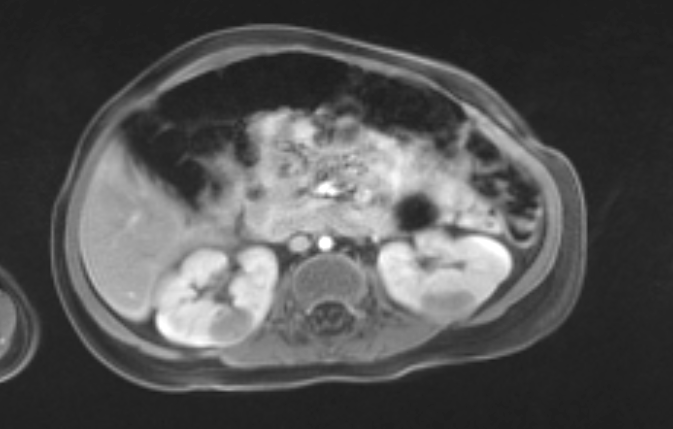

Figure 10 Echogenic renal mass on screening ultrasound in a patient with WAGR syndrome.

Figure 11 MRI confirmed multiple masses (same patient as Figure 10).

Renal Blood Flow

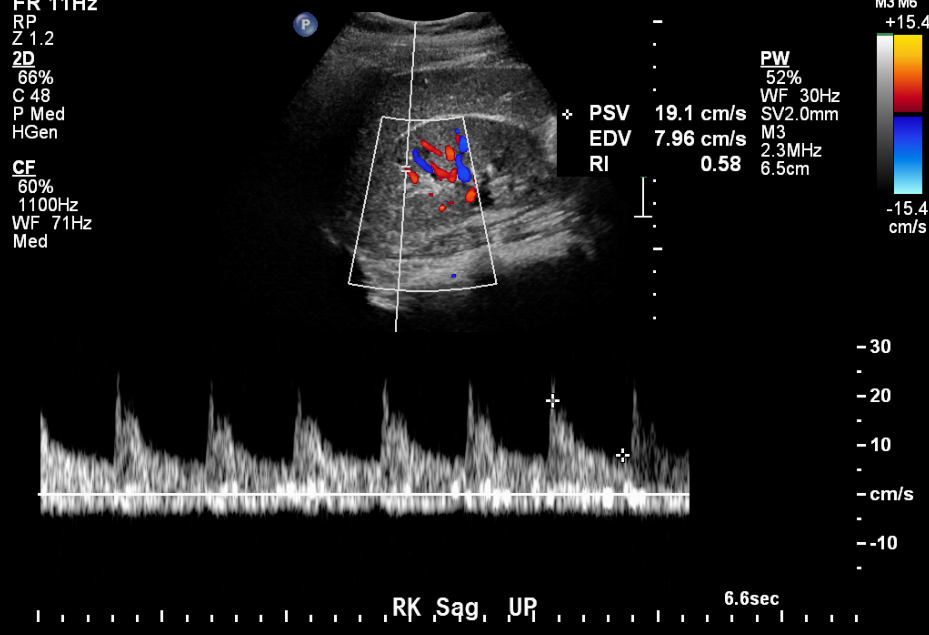

Ultrasound provides valuable information in cases of suspected renal artery stenosis.

Figure 12 Normal arterial tracing in an 11 year old with hypertension.

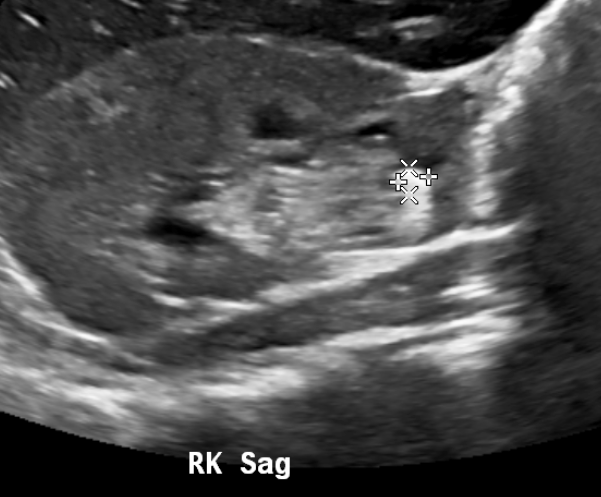

Renal Calculi

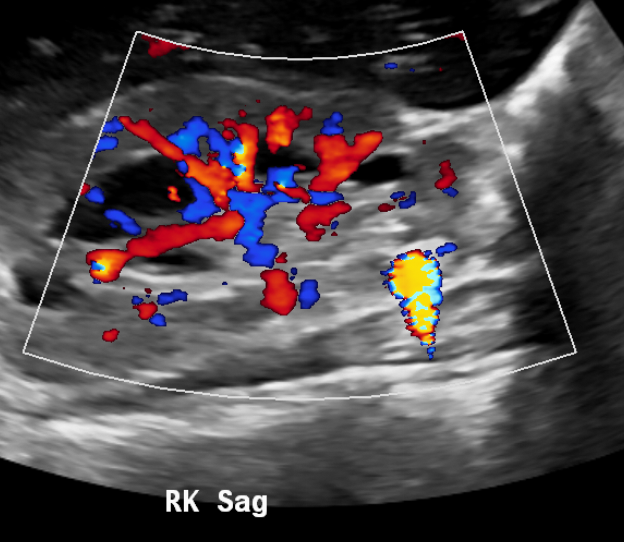

Obstructing calculi may be directly visible by ultrasound or may be inferred by the presence of a dilated collecting system on the symptomatic side. Twinkling artifact can be exploited to detect stones.

Figure 13 Calculus at the lower pole of the right kidney.

Figure 14 Twinkling artifact improves conspicuity of calculi.

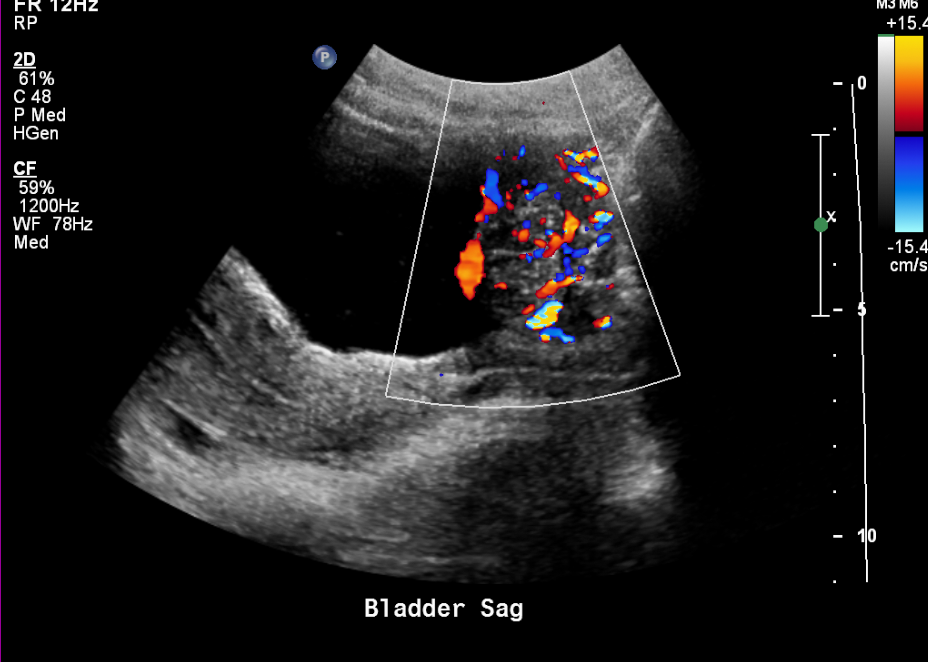

Bladder Abnormalities

An adequately distended bladder can be assessed for wall thickening, trabeculation, debris or stones. Bladder masses may be incidentally found. Post void images are useful in patients with suspected dysfunctional voiding.

Figure 15 Highly vascular bladder mass in a teenager.

Technique:

- Full bladder (in toilet trained child).

- Bladder scanned first before remainder of abdomen to prevent early emptying of the bladder.

- Sagittal views of the kidneys; best for length. Ideally, the sonographer should review prior ultrasounds to get a sense of the expected renal length.

- Transverse view at upper, interpolar, and lower pole; best for intrarenal collecting system dilation. An extrarenal pelvis seen in the sagittal plane can mimic mild intrarenal collecting system dilation.

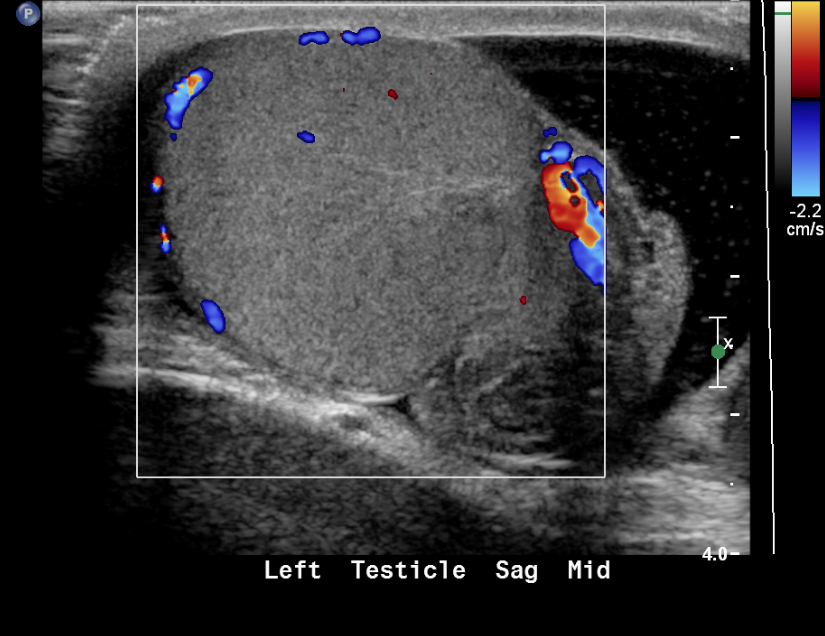

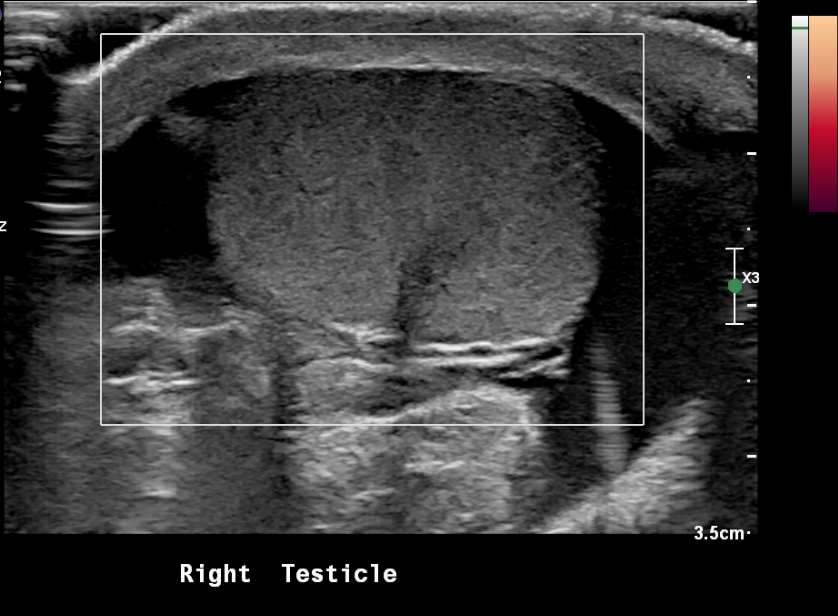

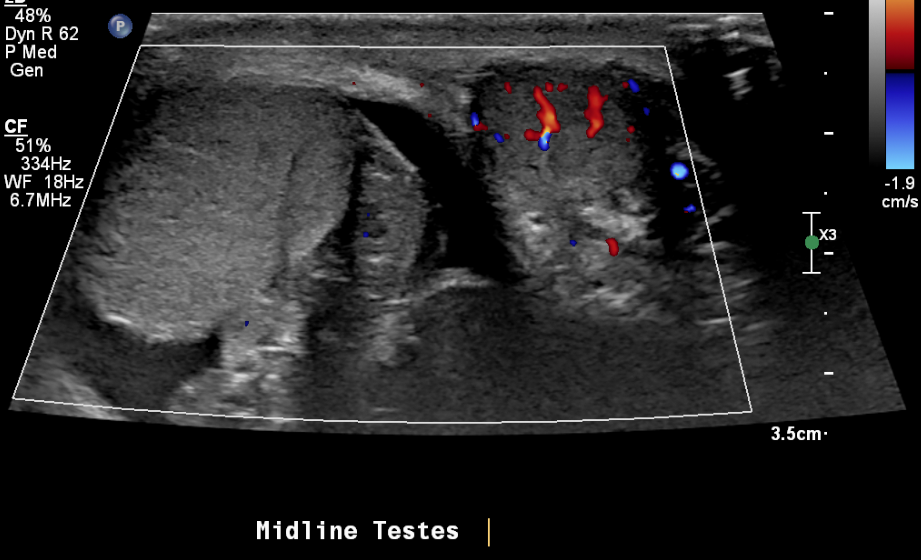

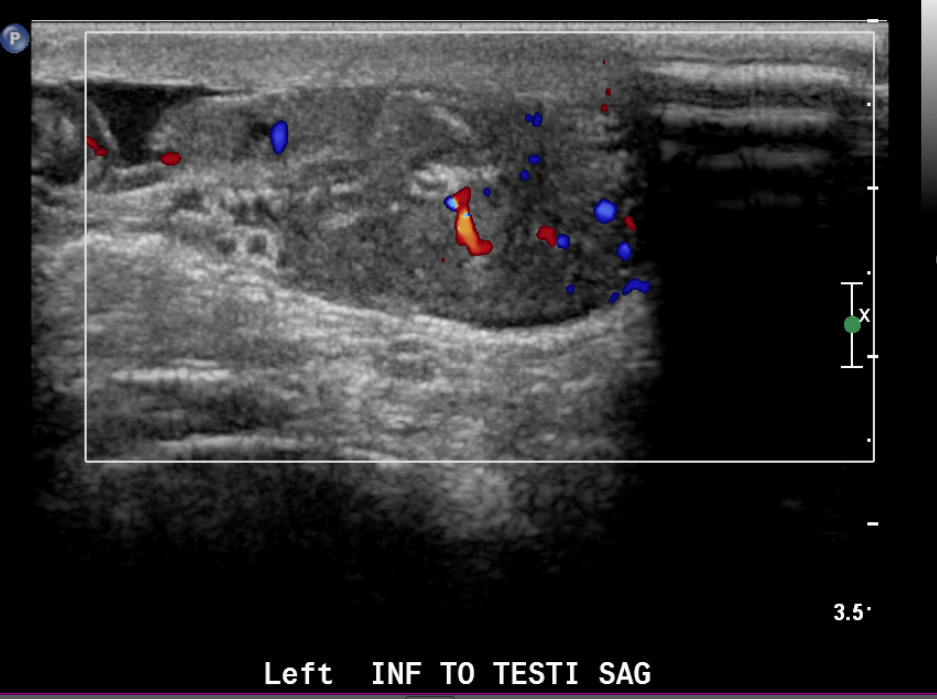

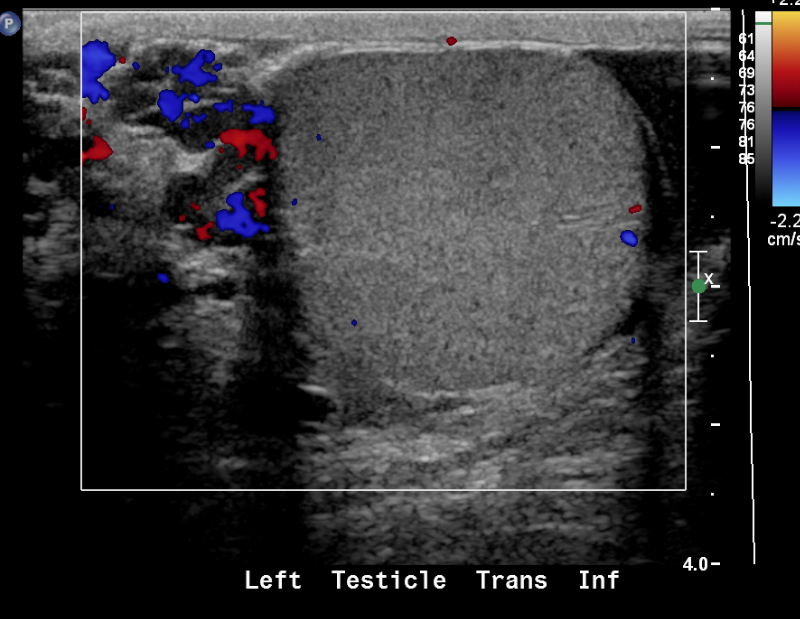

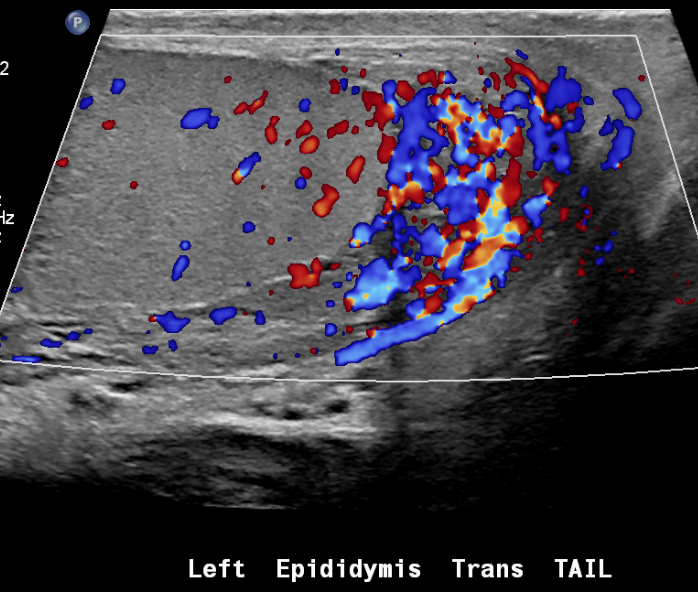

Scrotal Ultrasound

Ultrasound is the modality of choice to assess the scrotum in the setting of pain or palpable abnormality.12

Technique:

- Images of the testes in greatest dimension in two planes and measurements

- Images of the epididymal head (older boys) and measurements

- Color Doppler showing both testes

- Spectral Doppler showing arterial flow in both testes

- Views of the spermatic cords (ideally motion clips)

- Document hydrocele or varicocele if present

Figure 16 Bilateral hydroceles in a neonate

Figure 17 Non-communicating hydrocele in a neonate

Figure 18 Inguinal hernia in a neonate

Figure 19 Torsed testicle with absence of color flow

Figure 20 Torsed testicle with absence of blood flow on power Doppler

Figure 21 Torsed right testicle and normal blood flow to the left testicle

Figure 22 Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma in a teenager with painless palpable mass

Figure 23 Color image of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma

Figure 24 Varicocele

Figure 25 Epididymitis

Radiography

Radiographs use the difference in radiographic density of the various body parts to create an image (air, fat, fluid, bone, and metal). Modern radiographs are stored using a picture archiving and communication system (PACS), which is a digital imaging system. Advantages of PACS include improved resolution of the images and the ability to instantly and remotely share access.

Abdominal radiographs are often obtained in the acute setting (acute abdominal pain) to assess the bowel gas pattern and exclude free air (two views usually required for the latter).

Other potential findings:

- Soft tissue calcifications

- Large abdominal masses

- Organomegaly

- Bone abnormalities

- Support device positioning (e.g. ureteral stents)

A single supine abdominal radiograph is also commonly obtained by pediatric urologists in the outpatient setting for known or suspected constipation. By expert consensus, this is not indicated in children with large amounts of stool by rectal exam.13 There may be an indication for the practice in cases where a rectal exam is not possible (such as a traumatic history). The provider should remember that abdominal radiographs can result in a non-trivial radiation burden over time.

Figure 26 Abdominal radiograph showing mass effect in the right upper quadrant

Voiding Cystourethrography and Voiding Urosonography

VCUG is a specialized radiology procedure that is primarily used to assess for the presence of vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) and to assess urethral morphology. The rationale has been the presumed link between reflux and post infectious scarring. Despite thirty years of study since the beginning of routine antibiotic prophylaxis for reflux, questions remain. Cystograms are less frequently performed than in the past, and watchful waiting is often preferred over antibiotic prophylaxis.14 Voiding studies have traditionally been performed using fluoroscopy. A transition is underway in the United States toward the use of contrast enhanced ultrasound (ceUS). In Europe, contrast enhanced ultrasound has been performed since the 1990s and has been widely available since the early 2000s. However, ultrasound contrast agents were not approved for use in the US until 2016. There remains debate as to the sensitivity of ceVUS for urethral anomalies in the male infant. As of this writing, ACR appropriateness criteria still recommend VCUG over ceVUS in that setting, despite the existence of review articles showing excellent depiction of urethral anatomy by ceVUS.8,15,16

Fluoroscopy is still frequently used, including at this author’s institution, even though it exposes the patient to ionizing radiation. Another disadvantage of traditional fluoroscopy is that it requires the patient to lie flat to void; this is often difficult for toilet trained patients.

Aseptic bladder catheterization is required for both types of test, and is often the most difficult part of the exam for the patient. A small feeding tube (5 Fr to 10 Fr depending on the patient size and age) is passed via the urethra into the bladder. The use of sedation in children between about two and six years is controversial. The potential risks of sedation must be weighed against the harm done by psychological stress. The use of an octagon board or similar to immobilize the patient is likewise controversial. Some pediatric radiologists prefer to use the board in older infants or young toddlers. A child life professional is a valuable asset during these studies and can be a comforting presence for both the patient and the accompanying parent.

Once the catheter is in place and the bladder is emptied, contrast material is instilled under fluoroscopic (or sonographic) observation. The sonographic exam may use a blood pressure cuff to infuse contrast at a gentle pressure. For VCUG, contrast is instilled under gravity. The standard images obtained for both VCUG and ceVUS are essentially the same.

VCUG Technique:

- Fluoroscopic spot of abdomen (baby) or level of kidneys and level of bladder (older child)

- Spot or last image hold of bladder at initial fill (ureterocele evaluation)

- Intermittent checks to assess for reflux

- Near predicted bladder capacity, obtain bilateral oblique last image hold or spots

- At first void, check for reflux

- Second cycle (at least) in infant or febrile UTI patient

- Lateral voiding view of urethra in male patient (ideally with catheter out)

Voiding urosonography standard images will mostly be similar, with the exception of the initial scout view. Panoramic views can assist in extending the field of view in sonography. However, smaller field of view remains a limitation of ultrasound.

Care should be taken to fill the bladder adequately and not to overfill. A useful bladder capacity formula (for children over age 12 months) is age plus 2 multiplied by 30 for the predicted bladder capacity (in mL). A newborn can be expected to hold about 50 mL. Oblique fluoroscopic spots or at least last image holds should be obtained with maximal bladder distension to assess for low grade reflux (which can be obscured in the AP projection). Tapping on the bladder, gentle massage over the belly or warm water sprinkled on the skin can be helpful to induce young children to void. Sedation can occasionally make voiding more difficult for patients. Overfilling (to more than twice the predicted capacity) is to be avoided, as it can make this problem more likely.

- Indications

- Vesicoureteral reflux

- Studying the urethra during voiding

- Bladder abnormalities

- Contraindications

- Acute urinary tract infection

- Previous severe contrast reaction

- Patient preparation

- Patient should void prior to investigation (young children can have the bladder drained prior to filling).

- Antibiotic cover with Trimethoprim 2 mg/kg/dose once daily for 3 days prior to investigation (in children not on prophylactic antibiotics)

- Editor’s note: The evidence for this is limited and the practice is not universal.

- Complications

- Contrast related reactions

- Urinary tract infection

- Bladder over distension and rupture

- Catheter trauma

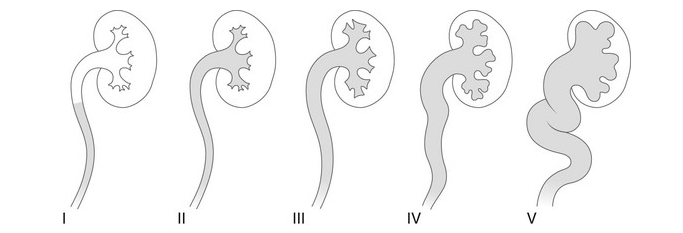

- Findings

- Grade I – reflux into non-dilated ureter

- Grade II – reflux into the renal pelvis and calyces without dilatation

- Grade III – mild/moderate dilatation of the ureter, renal pelvis and calyces with minimal blunting of the fornices

- Grade IV – dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces with moderate ureteral tortuosity

- Grade V – gross dilatation of the ureter, pelvis and calyces; ureteral tortuosity; loss of papillary impressions

Figure 27 Radiological grading of vesicoureteral reflux

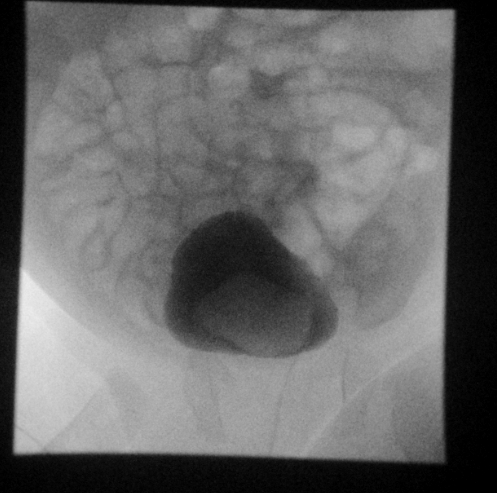

Figure 28 Ureterocele on fluoroscopic last image hold

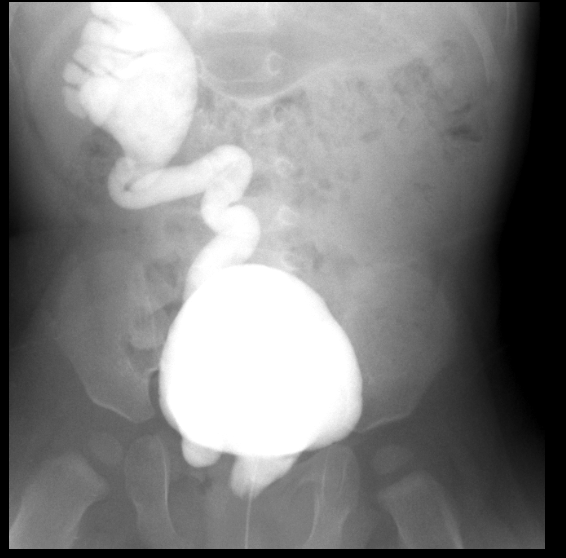

Figure 29 Grade 3 reflux into both kidneys

Figure 30 Grade 5 reflux on the right with ectopic insertion into urethra

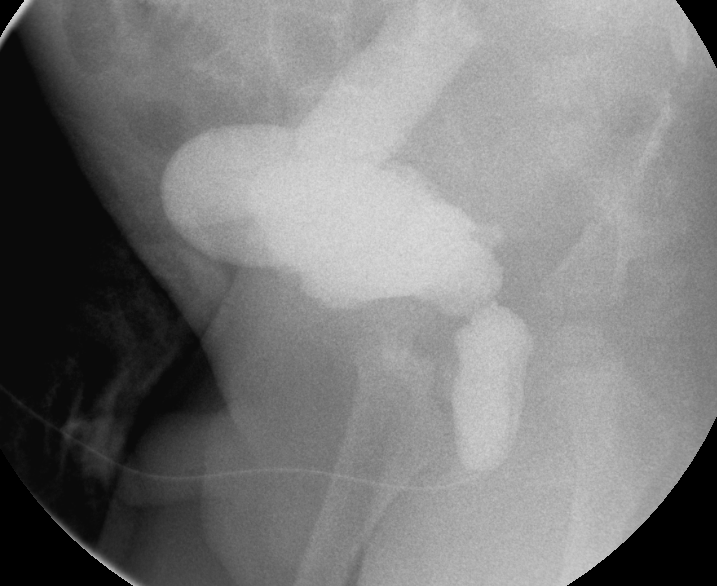

Figure 31 Dilated posterior urethra and massively dilated right ureter in the setting of posterior urethral valves

Radionuclide Studies

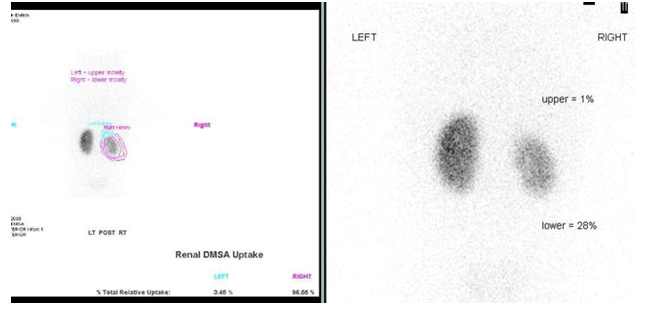

DMSA / Static Renal Scintigraphy

Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) binds to plasma proteins and is retained by the renal cortex on renal clearance, allowing functional assessment. Quantitative data on kidney function is crucial information unobtainable by ultrasound. Tc99m dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) scintigraphy has been considered the investigation of choice in the assessment of parenchymal damage due to acute or chronic pyelonephritis and provides data on differential kidney function. A bladder catheter is not required for the DMSA scan, since the radiotracer is not excreted into the urine. DMSA SPECT increases sensitivity, but sedation is required in young children in order to obtain high quality images.17 DMSA does not provide information about the collecting system or urodynamics.

- Indications

- Assess renal function

- Investigation of renal infection

- Renal congenital anomalies (e.g., horseshoe kidneys)

- Renal scarring and renal lesions

- Contraindications

- None

- Technique

- DMSA injected intravenously and images obtained by a Gamma camera 1–6 hours later.

- Information gathered

- Relative renal function

- Absolute uptake

Figure 32 DMSA scan showing scarring and reduced function of the right lower moiety of a duplicated kidney and a non-functioning upper moiety

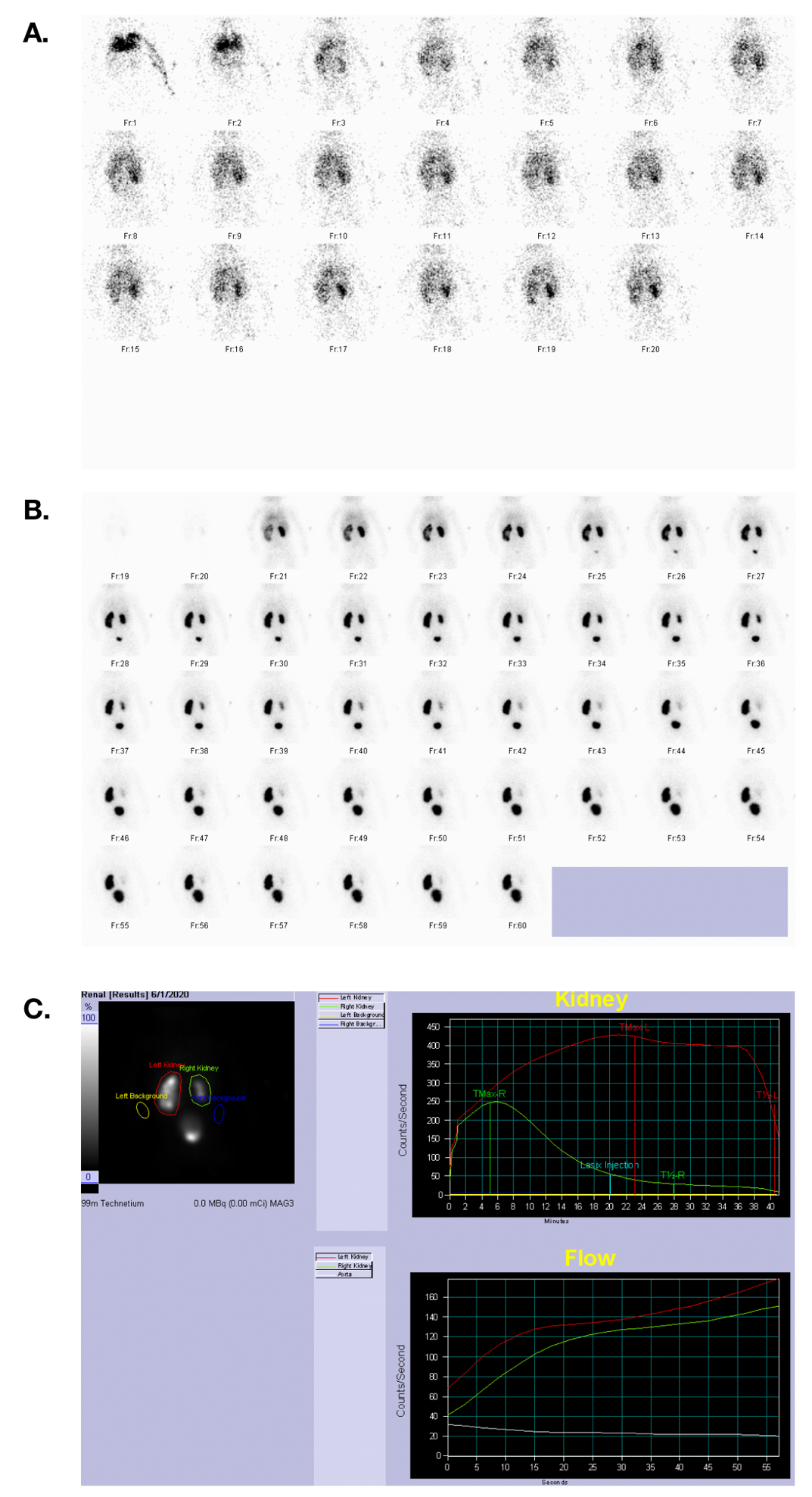

MAG-3 Scan / Dynamic Renal Scintigraphy

Mercaptoacetyletriglycerine (MAG-3) is highly plasma protein bound, so it is cleared by tubular secretion. Dynamic scintigraphy with MAG3 gives insight into kidney function and morphology. Sedation is required for young children (under about 5 years). The initial part of the study demonstrates perfusion and renal cortical function, allowing for distinction between reversible and irreversible lesions. The collecting system and urodynamics are then characterized with the aid of furosemide. A reassuring MAG-3 scan allows the pediatric urologist to safely observe a hydronephrotic patient in most cases.18

- Indications

- Obstructed vs non-obstructed system

- Renal artery stenosis

- Reflux disease

- Renal trauma

- Contraindications

- None

- Technique

- Hydrate patient and empty bladder

- Bladder catheter placement

- Injection of MAG-3

- Image at 2–3 minutes with a gamma camera for parenchymal phase

- Image beginning at 18–20 minutes

- Furosemide 1 mg/kg maximum 40 mg injection when dilated renal pelvis is full

- Sequential imaging for approximately 20 additional minutes

- Regions of interest drawn around kidneys

- Washout curves generated and t½ (time for half radiotracer to clear) calculated

- Information gathered

- Renal perfusion

- Cortical perfusion (split renal function)

- Parenchyma and whole kidney transit times

- T½ less than 10 minutes is normal

- T½ between 10 and 20 minutes indeterminate

- T½ greater than 20 minutes suggests obstruction

- Pitfalls

- Dehydration causing poor diuretic response

- Poor underlying renal function causing poor diuretic response

- Distended or non-compliant bladder (place catheter)

- Early high-grade reflux (prior VCUG/ VUS)

- Patulous collecting system delaying washout

- Regions of interest including spleen or liver

Figure 33 MAG 3 scan showing blood flow, excretory phase, and time activity curves in a patient with symmetric renal function and a left UPJ obstruction.

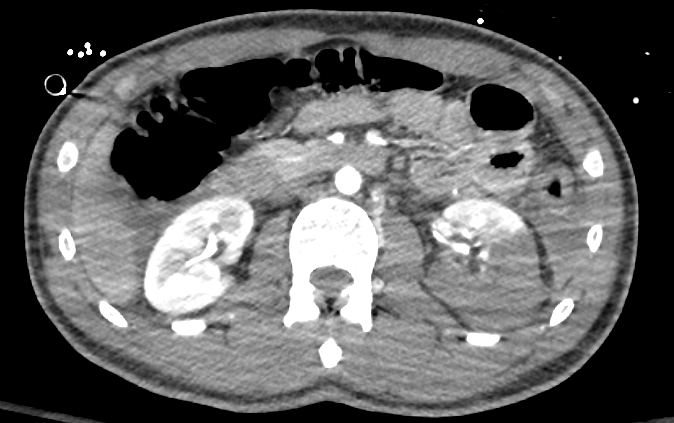

Computed Tomography

CT with IV contrast is the standard of care in children for evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. It is fast, widely available, and allows for monitoring by the radiologist in real time. Ideally, if a renal collecting system injury is identified, a second delayed view through the kidneys or bladder (depending on the level of suspected injury) can be obtained. With rare exceptions, this is the only appropriate use of multiphase CT scanning in the pediatric population. In the United States, MRI has largely replaced CT for tumor staging of the pediatric abdomen and pelvis.

Non-contrast CT can occasionally be helpful in the pediatric setting for the follow-up of renal and ureteral calculi, or diagnosis when ultrasound is unrevealing.2 Ultrasound may not reveal the obstructing calculus, especially if it is in the mid ureter (where shadowing bowel gas often blocks the sound beam). However, the presence of a dilated collecting system on the symptomatic side may allow the clinician to infer that a stone is present. In children with known calculi or conditions predisposing to calculi, CT may be desired. Very low radiation doses can be employed to assess stone burden or for follow up after intervention for stones.19 Hematuria protocols (three phase CT with non-contrast, contrast, and delayed phases) are not appropriate for children due to the high radiation burden.2

In the United States, MRI has largely replaced CT for tumor staging of the pediatric abdomen and pelvis.20 However, CT angiography is occasionally requested by our pediatric surgeons for planning purposes. CTA shows organ relationships and vascular anatomy with fewer artifacts and higher resolution than MR, allowing the surgeon to plan a more precise approach in cases of Wilms, neuroblastoma, or other malignancies. Because CT angiography requires a faster injection of contrast and has a higher radiation burden, these scans should be actively monitored by a pediatric radiologist.

Figure 34 Contrast enhanced CT showing high grade renal laceration of left kidney.

Figure 35 Delayed view through the kidney rules out disruption of the collecting system.

Figure 36 CT stone study for patient with cystinuria; note partially visible bilateral stents.

Figure 37 CT angiogram with 3D reconstruction in a cancer patient with complex arterial anatomy; three renal arteries are mapped out for each moiety

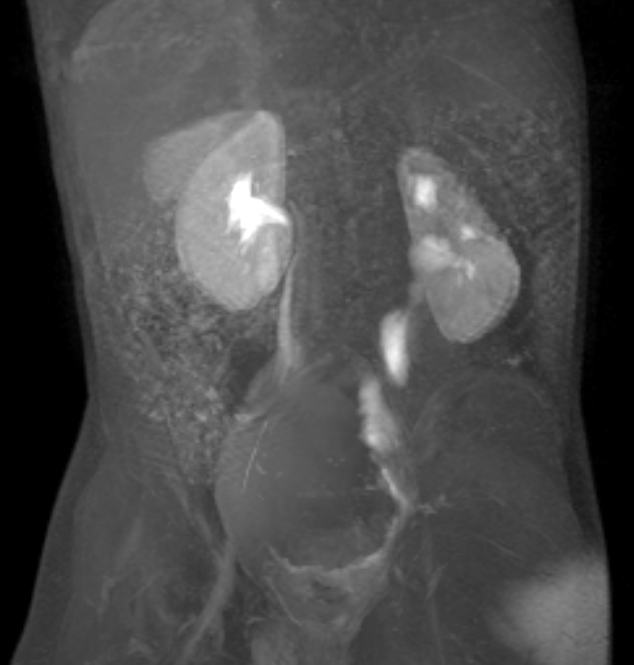

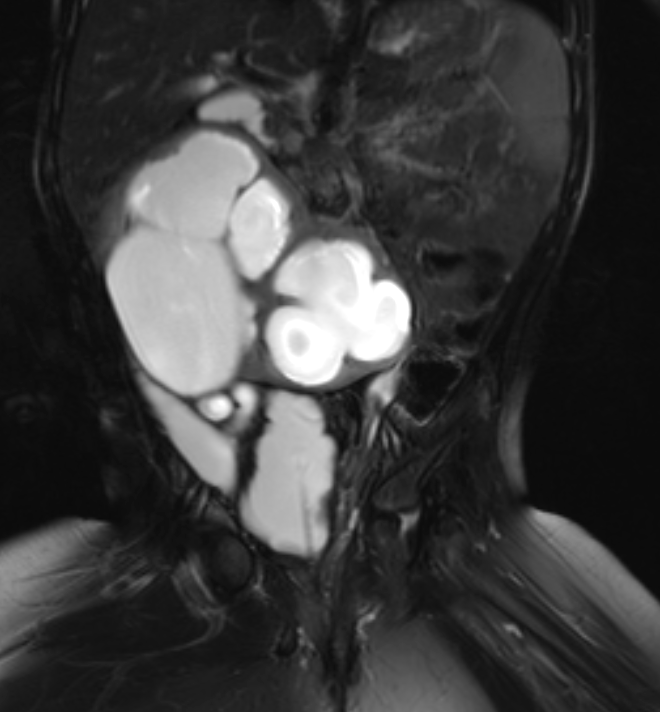

MRI

MRI exploits the magnetic properties of the hydrogen nucleus to produce mathematical information about the soft tissues of the human body, which can then be transformed into a detailed image. It is superior to any other modality for soft tissue contrast and does not use ionizing radiation. These advantages have made it the modality of choice for most cancer staging in the abdomen and pelvis. Numerous MRI pulse sequences are commercially available. MRI is therefore tailored to the clinical question (more so than CT), requiring specific protocols.

The resolution of MRI remains lower than CT (being about one order of magnitude inferior to CT in this respect), and evaluation of lung tissue is still limited in the clinical setting. MRI is also time-consuming and noisy, necessitating some form of sedation in most children under the age of about eight years. Whereas adult patients can (usually) follow breath hold instructions, this is difficult or impossible for young children. Software allowing for free-breathing scanning is essential for MRI body imaging in children.21 These sequences typically take longer than a breath hold sequence, but can still be obtained fairly quickly (in approximately three minutes). Duration of an MRI scan may last anywhere from thirty minutes to over an hour depending on the specific protocol.

Assessment of the urinary tract is called magnetic resonance urography (MRU). MRU is capable of providing both anatomic and functional information with one exam.8 MRU correlates well with Lasix renal scanning in terms of assessing renal function. Patients are hydrated with normal saline (approximately 10 mL/kg) and Lasix is administered at the start of the scan, in a dose of 1 mg/kg up to a maximum of 20 mg. In cases of suspected ureteropelvic junction obstruction, it may help to image the patient in the prone position or on the side contralateral to the suspected obstruction. In sedated patients, a Foley catheter can be placed.8 MRU for sedated patients is a cooperative enterprise necessitating good communication between the urologist, the radiology team and the sedation or anesthesia team.

MR angiography spares the patient radiation but has lower resolution and is more susceptible to artifacts than CTA.

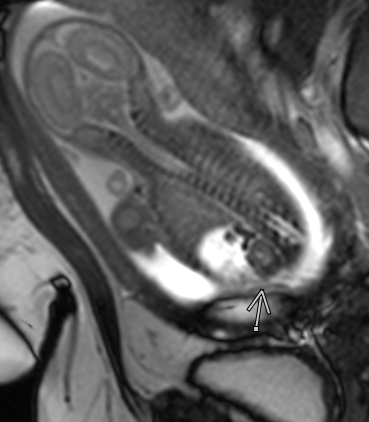

In fetal diagnosis, MRI is a complimentary modality to ultrasound. Fast pulse sequences are essential for fetal imaging. While fetal MRI is most frequently requested for further evaluation of a brain anomaly, it can provide additional information about the fetal urinary tract as well. It can be especially useful in the context of surgical planning for complex urogenital anomalies.22 In general, image quality in fetal MRI improves later in gestation.

-

MRI indications in pediatrics

- Staging of cancers

- Suspected renal mass

- Screening of patients at risk for tumor (e.g. TS, VHL)

- May be appropriate for complicated pyelonephritis

-

MR urography

- Method

- Fluid sensitive urography using heavily weighted T2 MRI techniques

- Excretory MR urography using T1 weighted contrast enhanced scans and furosemide

- Indications

- Collecting system anatomy

- Determine level of obstruction in renal tracts (intrinsic and extrinsic)

- Congenital anomalies

- Method

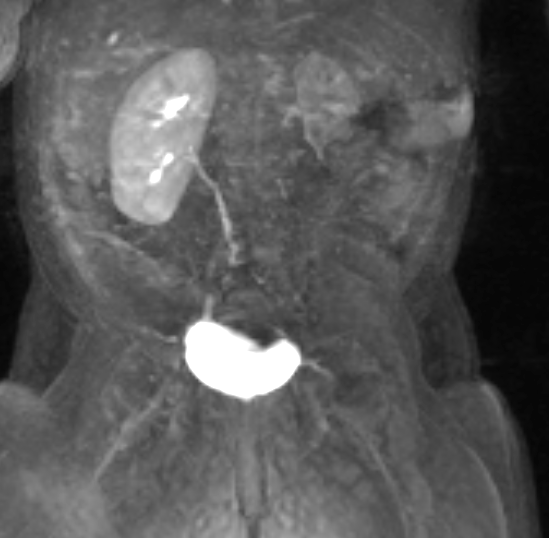

Figure 38 Fluid sensitive fat-suppressed MR image showing dilated left upper pole in a duplicated kidney.

Figure 39 Post contrast dynamic MR image shows a dilated but non-obstructed left megaureter.

Figure 40 Fluid sensitive fat-suppressed MR image shows a hydronephrotic horseshoe kidney and a neurogenic bladder morphology.

Figure 41 Dynamic post-contrast MR series confirms obstruction of the horseshoe kidney.

Figure 42 Fluid sensitive fat-suppressed MR image shows a small dysplastic left kidney.

Figure 43 Dynamic post-contrast MR series shows delayed and minimal enhancement of the dysplastic kidney indicating limited function.

Figure 44 Dynamic post-contrast MR series shows small right kidney in a patient with prune belly and bilateral vesicoureteral reflux.

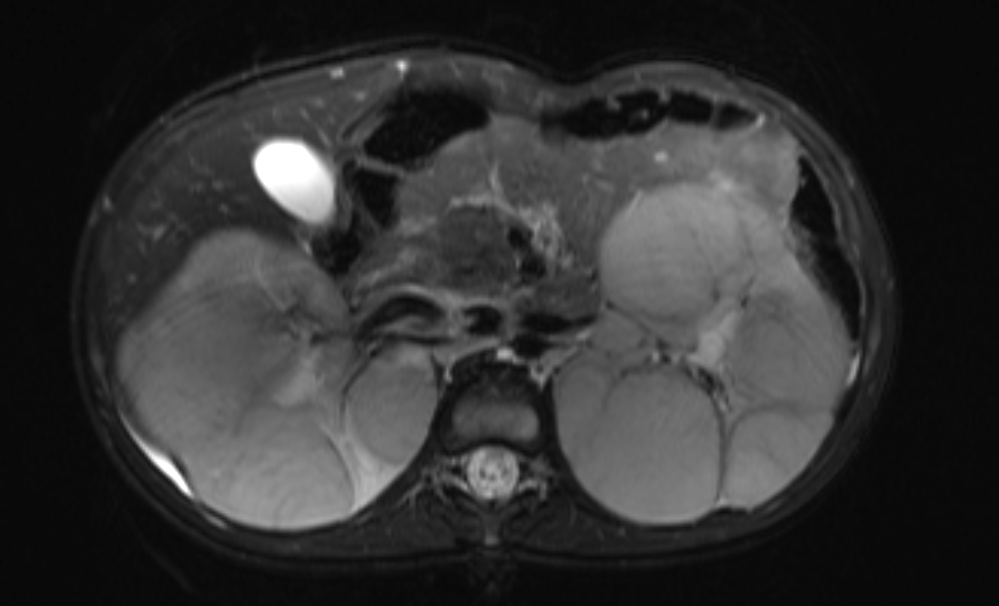

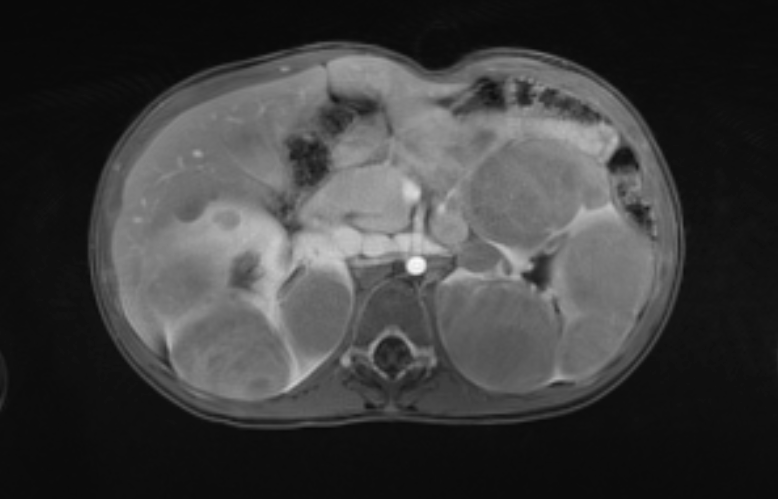

Figure 45 Fluid sensitive fat-suppressed MR image showing replacement of the renal parenchyma with multiple masses in a patient with nephroblastomatosis.

Figure 46 Post contrast MR images show enhancement characteristics of the masses.

Figure 47 View of a normal kidney and adrenal gland in a fetus with ascites

Intervention in Pediatric Urology

Interventional procedures are integral to the management of pediatric urological conditions.23,24 The pediatric radiology subspecialty is distinct from both pediatric radiology and adult interventional radiology, and pediatric IR practitioners are remain small in number, despite growth over the last fifteen years.25

Drainage of Urinary Tracts Secondary to Obstruction/Nephrostomies

- Should be reserved for patients where retrograde drainage approach is not possible

- Pre procedural preparation would include assessing risk of bleeding and infection

- Antibiotic cover

- Access to renal collection system either via ultrasound, fluoroscopy or CT guidance.

- Complications

- Hemorrhage

- Sepsis

- Organ injury

- Thoracic injury (i.e., pneumothorax)

Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

- Reserved for patients who are not candidates for ureterscopy or shock wave lithotripsy

- Two step procedure

- Access to collecting system by radiologist using ultrasound/fluoroscopy

- Removal of stone by urologist

Other Interventions

- Ureteric stenting

- Ureteric dilatation secondary to stricture

- Biopsy of renal tumors

- Embolization of renal tumors or renal hemorrhage

Suggested Readings

- Brown BP, Simoneaux SF, Dillman JR, Rigsby CK, Iyer RS, Alazraki AL, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Antenatal Hydronephrosis–Infant. J Am Coll Radiol 2020; 17 (11): S367–s379. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.017.

- Chung EM, Soderlund KA, Fagen KE. Imaging of the Pediatric Urinary System. Radiol Clin North Am 2017; 55 (2): 337–357. DOI: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.10.010.

- Dillman JR, Rigsby CK, Iyer RS, Alazraki AL, Anupindi SA, Brown BP, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Hematuria-Child. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 15 (5): S91–s103. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.022.

- Dillman JR, Trout AT, Smith EA. MR urography in children and adolescents: techniques and clinical applications. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016; 41 (6): 1007–1019. DOI: 10.1007/s00261-016-0669-z.

- Duran C, Beltrán VP, González A, Gómez C, Riego Jdel. Contrast-enhanced Voiding Urosonography for Vesicoureteral Reflux Diagnosis in Children. Radiographics 2017; 37 (6): 1854–1869. DOI: 10.1148/rg.2017170024.

- Chow JS, Koning JL, Back SJ, Nguyen HT, Phelps A, Darge K. Classification of pediatric urinary tract dilation: the new language. Pediatric Radiology 2017; 47: 1109–1115.

References

- Strauss KJ, Goske MJ, Kaste SC, Bulas D, Frush DP, Butler P, et al.. Image Gently: Ten Steps You Can Take to Optimize Image Quality and Lower CT Dose for Pediatric Patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1976; 194 (4): 868–873. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.09.4091.

- Dillman JR, Rigsby CK, Iyer RS, Alazraki AL, Anupindi SA, Brown BP, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Hematuria-Child. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 15 (5): S91–s103. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.022.

- Goodman TR, Mustafa A, Rowe E. Pediatric CT radiation exposure: where we were, and where we are now. Pediatr Radiol 2019; 49 (4): 469–478. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-018-4281-y.

- Kuebker J, Shuman J, Hsi RS, Herrell SD, Miller NL. Radiation From Kidney-Ureter-Bladder Radiographs Is Not Trivial. Urology 2019; 125: 46–49. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.11.035.

- Dong S-Z, Zhu M, Bulas D. Techniques for minimizing sedation in pediatric MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 50 (4): 1047–1054. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.26703.

- Drugs ACRC on, Media C. ACR Manual On Contrast Media. American College of Radiology; 2022.

- Brown BP, Simoneaux SF, Dillman JR, Rigsby CK, Iyer RS, Alazraki AL, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Antenatal Hydronephrosis–Infant. J Am Coll Radiol 2020; 17 (11): S367–s379. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.09.017.

- Karmazyn BK, Alazraki AL, Anupindi SA, Dempsey ME, Dillman JR, Dorfman SR, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Urinary Tract Infection–Child. J Am Coll Radiol 2018; 14 (5): S362–s371. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.02.028.

- Kalish JM, Doros L, Helman LJ, Hennekam RC, Kuiper RP, Maas SM, et al.. Surveillance Recommendations for Children with Overgrowth Syndromes and Predisposition to Wilms Tumors and Hepatoblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23 (13): e115–e122. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-17-0710.

- Wang CL, Aryal B, Oto A, Allen BC, Akin O, Alexander LF, et al.. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Onset of Scrotal Pain-Without Trauma, Without Antecedent Mass. J Am Coll Radiol 2019; 16 (5): S38–s43. DOI: 10.1016/j.jacr.2019.02.016.

- Rerksuppaphol S, Barnes G. Guidelines for Evaluation and Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux In Infants and Children: Recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006; 35 (4): 583. DOI: 10.1097/00005176-200210000-00024.

- Chung EM, Soderlund KA, Fagen KE. Imaging of the Pediatric Urinary System. Radiol Clin North Am 2017; 55 (2): 337–357. DOI: 10.1016/j.rcl.2016.10.010.

- Barnewolt CE, Acharya PT, Aguirre Pascual E, Back SJ, Beltrán Salazar VP, Chan PKJ, et al.. Contrast-enhanced voiding urosonography part 2: urethral imaging. Pediatr Radiol 2021; 51 (12): 2368–2386. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-021-05116-6.

- Duran C, Beltrán VP, González A, Gómez C, Riego Jdel. Contrast-enhanced Voiding Urosonography for Vesicoureteral Reflux Diagnosis in Children. Radiographics 2017; 37 (6): 1854–1869. DOI: 10.1148/rg.2017170024.

- Sheehy N, Tetrault TA, Zurakowski D, Vija AH, Fahey FH, Treves ST. Pediatric 99mTc-DMSA SPECT Performed by Using Iterative Reconstruction with Isotropic Resolution Recovery: Improved Image Quality and Reduced Radiopharmaceutical Activity. Radiology 2009; 251 (2): 511–516. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2512081440.

- Wood LN, Souders CE, Freedman AL. Is a Reassuring MAG-3 Diuretic Renal Scan Really Reassuring? Curr Urol 2014; 8 (4): 178–182. DOI: 10.1159/000365713.

- Rodger F, Roditi G, Aboumarzouk OM. Diagnostic Accuracy of Low and Ultra-Low Dose CT for Identification of Urinary Tract Stones: A Systematic Review. Urol Int 2018; 100 (4): 375–385. DOI: 10.1159/000488062.

- Voss SD. Staging and following common pediatric malignancies: MRI versus CT versus functional imaging. Pediatr Radiol 2018; 48 (9): 1324–1336. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-018-4162-4.

- Darge K, Anupindi SA, Jaramillo D. MR Imaging of the Abdomen and Pelvis in Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Radiology 2011; 261 (1): 12–29. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.11101922.

- Calvo-Garcia MA, Kline-Fath BM, Levitt MA, Lim F-Y, Linam LE, Patel MN, et al.. Fetal MRI clues to diagnose cloacal malformations. Pediatr Radiol 2011; 41 (9): 1117–1128. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-011-2020-8.

- Hwang JY, Shin JH, Lee YJ, Yoon HM, Cho YA, Kim KS. Percutaneous nephrostomy placement in infants and young children. Diagn Interv Imaging 2018; 99 (3): 157–162. DOI: 10.1016/j.diii.2017.07.002.

- Sweed Y, Singer-Jordan J, Papura S, Loberant N, Yulevich A. Use of angiographic embolization in pediatric abdominal trauma-induced solid organ injuries. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2016; 8 (11): 65–68. DOI: 10.5505/tjtes.2018.00056.

- Kaufman CS, James CA, Harned RK, Connolly BL, Roebuck DJ, Cahill AM, et al.. Pediatric interventional radiology workforce survey: 10-year follow-up. Pediatr Radiol 2017; 47 (6): 651–656. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-017-3796-y.

- Pierce CB, Muñoz A, Ng DK, Warady BA, Furth SL, Schwartz GJ. Age- and sex-dependent clinical equations to estimate glomerular filtration rates in children and young adults with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2021; 99 (4): 948–956. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.10.047.

- Dillman JR, Trout AT, Smith EA. MR urography in children and adolescents: techniques and clinical applications. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2016; 41 (6): 1007–1019. DOI: 10.1007/s00261-016-0669-z.

- Chow JS, Koning JL, Back SJ, Nguyen HT, Phelps A, Darge K. Classification of pediatric urinary tract dilation: the new language. Pediatric Radiology 2017; 47: 1109–1115.

Ultima atualização: 2024-02-16 22:01