56: Escroto agudo

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 30 minutos para leer.

Introducción

Un “escroto agudo” se refiere a la aparición rápida de un escroto doloroso y/o tumefacto. La torsión testicular (TT) es el diagnóstico más preocupante y el primero en la mente de cualquier clínico, y sin intervención precoz, el testículo corre riesgo de necrosis secundaria a isquemia prolongada. Una vez descartada la TT, pueden considerarse otras etiologías. En términos generales, el diagnóstico diferencial del escroto agudo pediátrico también incluye torsión del apéndice testicular, epididimitis, orquitis, hernia incarcerada, vasculitis, traumatismo testicular y celulitis. En este capítulo, destacaremos la evaluación de la torsión testicular, la torsión de los apéndices del testículo o del epidídimo, y la epididimitis. La causa principal de estos diagnósticos se relaciona con la anatomía del propio testículo o del epidídimo, mientras que los otros diagnósticos tienen causas secundarias de tumefacción escrotal, dolor o infección (p. ej., orquitis por paperas secundaria al virus de la familia Paramyxoviridae). El diagnóstico y el manejo de estos otros diagnósticos del diagnóstico diferencial requieren el tratamiento de la causa primaria y se abordan en otra parte de este libro de texto.

Anatomía y Embriología

El escroto es un saco de piel y tejido subyacente inferior al falo en el que se alojan los testículos y el epidídimo. Por debajo de la piel se encuentra la fascia dartos, una continuación de la fascia de Colles del periné, la fascia dartos del pene y la fascia de Scarpa del abdomen. La fascia dartos es de naturaleza elástica. Aporta irrigación a la piel escrotal y, junto con el reflejo cremastérico del testículo, ayuda a regular la temperatura testicular contrayendo (elevando) o relajando (descendiendo) el escroto en su conjunto. El escroto está dividido en compartimentos laterales por el tabique escrotal. Internamente, el tabique está compuesto por fascia dartos engrosada. Externamente, el tabique se manifiesta como el rafe escrotal medio.

La túnica vaginal es el revestimiento seroso del interior del escroto que rodea los testículos. La túnica vaginal se deriva del proceso vaginal, una evaginación embrionaria del peritoneo abdominal que recorre la longitud del conducto inguinal hasta el escroto antes de su obliteración. Tras la obliteración de la porción inguinal, el saco distal remanente rodea al testículo y consta de dos capas: una capa visceral y una capa parietal. La capa visceral está adherida a la túnica albugínea, la superficie más externa del testículo. La capa parietal se refleja sobre la superficie interna del escroto.

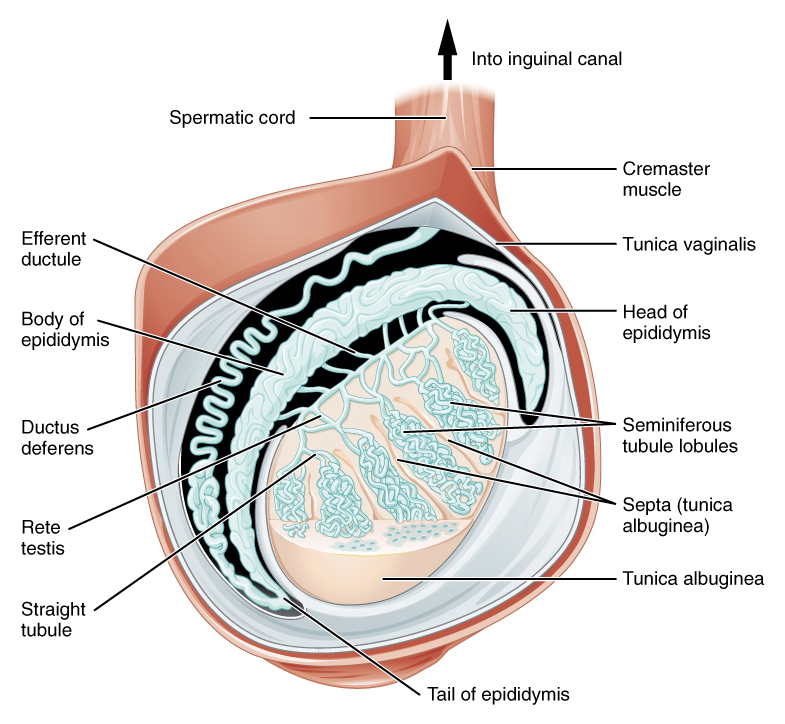

El testículo es una gónada masculina de forma ovoide situada en cada lado del escroto y que cumple funciones endocrinas y reproductivas mediante la producción de hormonas (principalmente testosterona) y espermatozoides. Los espermatozoides se producen en los túbulos seminíferos del testículo y viajan a través de la red testicular hacia los conductillos eferentes, que se conectan con la cabeza del epidídimo. El epidídimo es un conducto tortuosamente enrollado que se asienta sobre la cara posterolateral del testículo. Su función es almacenar y madurar los espermatozoides hasta su liberación a través del conducto deferente, en ruta hacia la ampolla del conducto deferente, el reservorio de espermatozoides maduros para la emisión.

El cordón espermático es una estructura importante contenida dentro del escroto. Se origina en el anillo inguinal profundo (interno) de la pared abdominal, atraviesa el conducto inguinal y pasa a través del anillo inguinal superficial (externo) hacia el escroto. El cordón espermático contiene nervios, vasculatura y conductos. Está rodeado por tres capas de tejido fascial (de superficial a profundo): la fascia espermática externa (una continuación de la fascia del oblicuo externo), el músculo cremáster (continuación de la musculatura del oblicuo interno) y la fascia espermática interna espermática (continuación de la fascia transversalis. Además de estas capas individuales, el cordón espermático incluye (Figura 1):

Vasculatura:

- Arteria testicular (una rama de la aorta)

- Arteria y vena cremastéricas (ramas de los vasos epigástricos inferiores)

- Arteria del conducto deferente (rama de la arteria vesical superior)

- Plexo pampiniforme (red venosa distal al anillo inguinal)

Nervios:

- Nervio ilioinguinal (se une al cordón espermático superficial a la fascia espermática externa desde dentro del canal inguinal para proporcionar sensibilidad al escroto superior y a la piel del pene)

- Rama genital del nervio genitofemoral (proporciona inervación motora al músculo cremáster y sensibilidad al escroto anterior)

- Nervios autonómicos

Otros:

- Conducto deferente

- Vasos linfáticos

- Conducto peritoneo-vaginal

Figura 1 Contenido distal del cordón espermático y la túnica vaginal. Atribución: OpenStax College

La diferenciación, el desarrollo y el descenso testicular se describen en otros capítulos.

Evaluación general y diagnóstico

En el paciente pediátrico que se presenta con dolor testicular agudo y/o tumefacción escrotal, se debe realizar una anamnesis y un examen físico minuciosos.

Se deben obtener elementos clave de la historia clínica del paciente, incluyendo la edad, la naturaleza del inicio del dolor (p. ej., inicio brusco o gradual, presencia de traumatismo), la localización e irradiación del dolor, y los síntomas asociados (p. ej., dolor abdominal, náuseas o vómitos, hematuria, disuria, fiebre, estreñimiento). Los síntomas asociados pueden ser útiles tanto para confirmar un diagnóstico de TT como para descartar TT en favor de otros diagnósticos. La TT suele presentarse con dolor abdominal, náuseas y/o vómitos. Por otro lado, la disuria y la presencia de fiebre sistémica sugerirían otra etiología, como epididimitis.

El examen físico debe incluir un examen abdominal y un examen genital. El examen abdominal debe incluir la evaluación del dolor a la palpación costovertebral como evidencia de dolor en el flanco, lo que puede representar un cólico ureteral con dolor referido a la ingle. También debe consignarse la evidencia de hernia o celulitis en la región inguinal.1 La presencia de dolor abdominal aislado debe seguir motivando un examen genital para descartar un escroto agudo, especialmente en niños más pequeños que no pueden comunicar adecuadamente sus necesidades, niños con retraso del desarrollo y niños con sensorio potencialmente alterado.2

El examen genital incluye la evaluación del escroto y de ambos testículos, comenzando con la inspección y seguida de la palpación. La inspección de la piel debe señalar eritema sugestivo de celulitis. En niños de piel más clara, puede observarse una leve tonalidad azulada (signo del ‘punto azul’) en la piel escrotal lateral en niños con torsión del apéndice testicular o del epidídimo, aunque este signo del examen físico está presente en una minoría de casos y no es pertinente en niños con piel más oscura.3 La palpación suave puede lograrse haciendo rodar toda la superficie testicular entre el pulgar y los dedos índices. Este examen a menudo es difícil de realizar en el contexto de TT debido al edema testicular y al hidrocele reactivo y tenso asociado. Debe señalarse un testículo en posición alta en comparación con el lado contralateral, lo cual sugiere TT (debido a la elevación del testículo a medida que el cordón espermático se retuerce y acorta). También es de interés la posición del testículo, ya sea vertical u horizontal. Es importante destacar que la deformidad en badajo de campana produce una posición horizontal y está presente en varones con una inserción superior anómala de la túnica vaginal al cordón espermático. Esta variante anatómica permite la rotación libre del testículo y predispone al paciente a torsión intravaginal (se discute más adelante). Obsérvese que esta anomalía es difícil de distinguir en un contexto normal y es poco probable establecerla en el contexto de TT secundario a edema y cambios cutáneos.

Las maniobras de examen adicionales pueden poner de manifiesto el diagnóstico:

- Las masas escrotales deben definirse mediante transiluminación (indicativa de un hidrocele) y el intento de reducción (indicativo de un proceso vaginal permeable)

- El reflejo cremastérico debe evaluarse frotando el muslo ipsilateral al testículo afectado. El reflejo normalmente provoca contracción cremastérica y elevación del testículo dentro del escroto. La ausencia del reflejo en un paciente que se presenta con dolor escrotal agudo sugiere clásicamente el diagnóstico de TT; este hallazgo tiene una sensibilidad del 100% y una especificidad del 66%.4 Sin embargo, en un niño pequeño, el arco reflejo puede estar poco desarrollado y ausente en un individuo por lo demás sano.5,6 Por lo tanto, es importante evaluar primero el reflejo cremastérico en el lado contralateral “normal” para establecer un examen basal.

- Elevar el contenido escrotal es una maniobra enseñada para distinguir entre epididimitis y TT. El alivio del dolor al elevar el escroto, clásicamente denominado signo de Prehn positivo, sugiere epididimitis y no es reproducible en la TT, aunque no siempre es una prueba confiable en niños.1

Las pruebas diagnósticas iniciales, que se discutirán más adelante, suelen incluir:

- Análisis de orina (UA) y cultivo de orina. Estas pruebas se realizan para descartar infección del tracto urinario y epididimitis bacteriana. Los niños que se presentan con TT generalmente no presentarán signos de infección en muestras de orina recolectadas adecuadamente

- Ecografía Doppler color (CDUS). Esta es una prueba confirmatoria que identifica la ausencia de flujo vascular a un testículo

Torsión testicular

Epidemiología

La incidencia reportada de la TT es tan alta como 1 en 4,000 en varones de 25 años o menos7 y tan baja como 3.8 por 100,000 en varones de 18 años o menos.8 La incidencia presenta una distribución bimodal, con picos en el primer año de vida (típicamente en el primer mes) y en el período puberal (12 años de edad). Esta distribución bimodal corresponde a la diferencia en la patogénesis en el recién nacido y en el período peripuberal (torsión extravaginal versus torsión intravaginal del cordón espermático, respectivamente).

Patogénesis

La TT ocurre cuando el testículo gira alrededor de su cordón espermático. El cordón torcido comprime la red venosa del testículo, provocando edema testicular, restricción del drenaje venoso y, más tarde, oclusión del flujo arterial de entrada. La isquemia prolongada es perjudicial y, si no se resuelve, reduce al mínimo la probabilidad de viabilidad testicular.

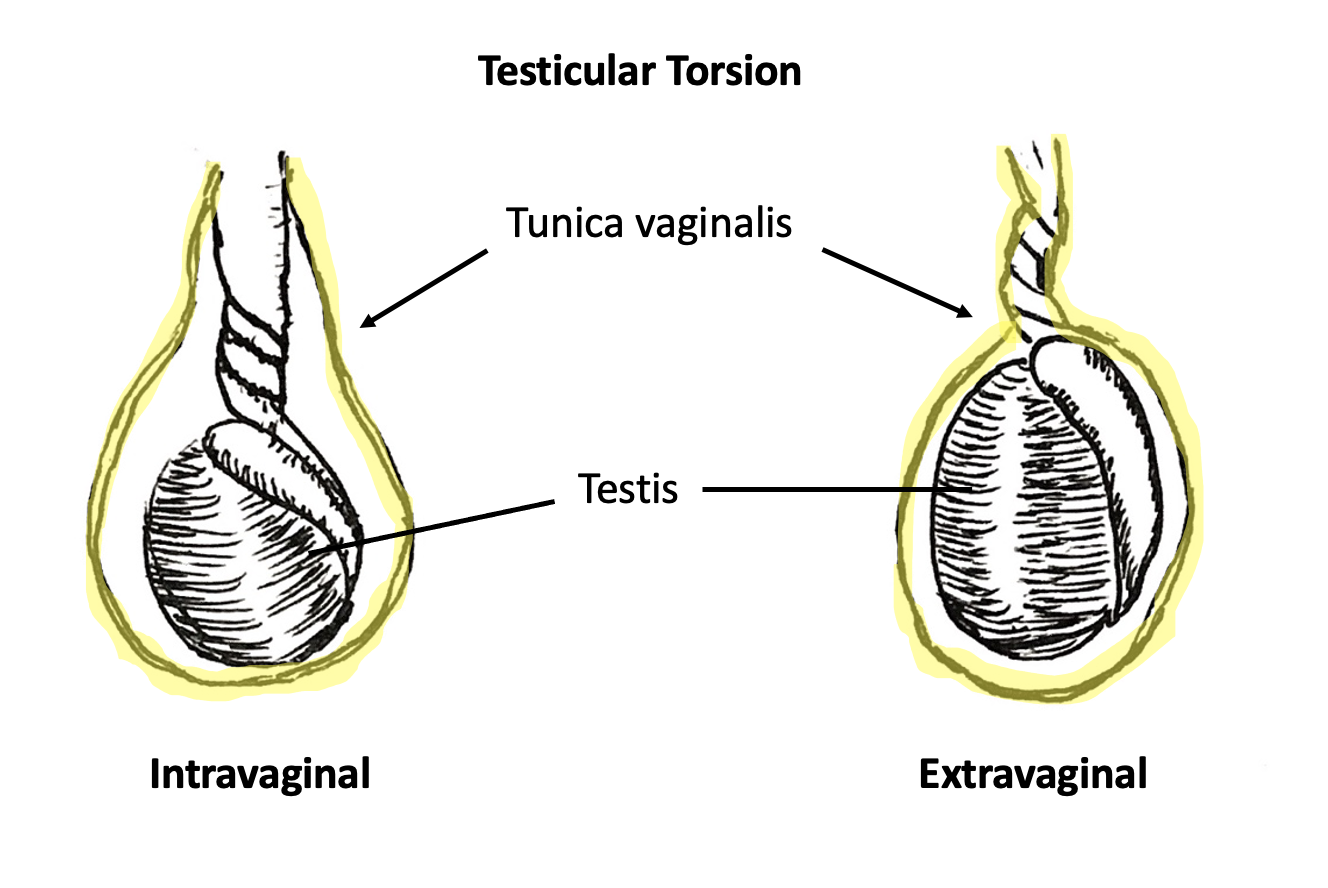

Existen dos tipos de TT: torsión intravaginal y extravaginal.

Torsión extravaginal ocurre cuando la túnica vaginal y su contenido, incluido el testículo, giran como una unidad alrededor del eje del cordón espermático. Este fenómeno es posible debido a capas escrotales no fusionadas en el período neonatal, lo que permite que la túnica vaginal se desplace dentro del compartimento hemiescrotal revestido por la fascia del dartos. La torsión extravaginal ocurre exclusivamente en el período neonatal o prenatal y se ha documentado que puede presentarse tan tarde como a los 1–3 meses después del nacimiento.9 La TT neonatal es rara en comparación con la torsión intravaginal, con una incidencia de 6.1 por 100,000.10

La torsión intravaginal ocurre cuando el testículo se tuerce alrededor del cordón espermático dentro de la túnica vaginal. La llamada “deformidad en badajo de campana” es el principal factor de riesgo que predispone a la torsión intravaginal. Normalmente, las capas visceral y parietal de la túnica vaginal están fusionadas posteriormente e inferiormente, lo que fija el testículo dentro del compartimento de la túnica vaginal. En los varones con una deformidad en badajo de campana, la túnica vaginal recubre completamente el testículo, el epidídimo y la porción distal del cordón espermático, sin puntos de fusión entre las capas visceral y parietal.11 Una serie de autopsias informó una incidencia del 12% de la deformidad en badajo de campana, la cual, notablemente, es mayor que la incidencia de TT.12 La alta incidencia de deformidad en badajo de campana bilateral justifica la orquidopexia profiláctica en el lado contralateral, no afectado.

Debe señalarse que no se considera que la torsión perinatal (extravaginal) esté asociada con una deformidad tipo badajo de campana contralateral ni con riesgo posterior de TT intravaginal. Por el contrario, la torsión intravaginal de un lado probablemente indica la presencia de una deformidad tipo badajo de campana contralateral y riesgo de una torsión intravaginal contralateral posterior, metacrónica. En una serie de un solo cirujano de 50 pacientes consecutivos llevados al quirófano para exploración de un testículo no palpable en la que se evidenció un resto testicular, solo 1 paciente mostró evidencia de una deformidad tipo badajo de campana contralateral. Los autores contrastaron esto con 27 casos francos de TT en niños mayores, en los que 21 (78%) tenían una deformidad tipo badajo de campana contralateral.13

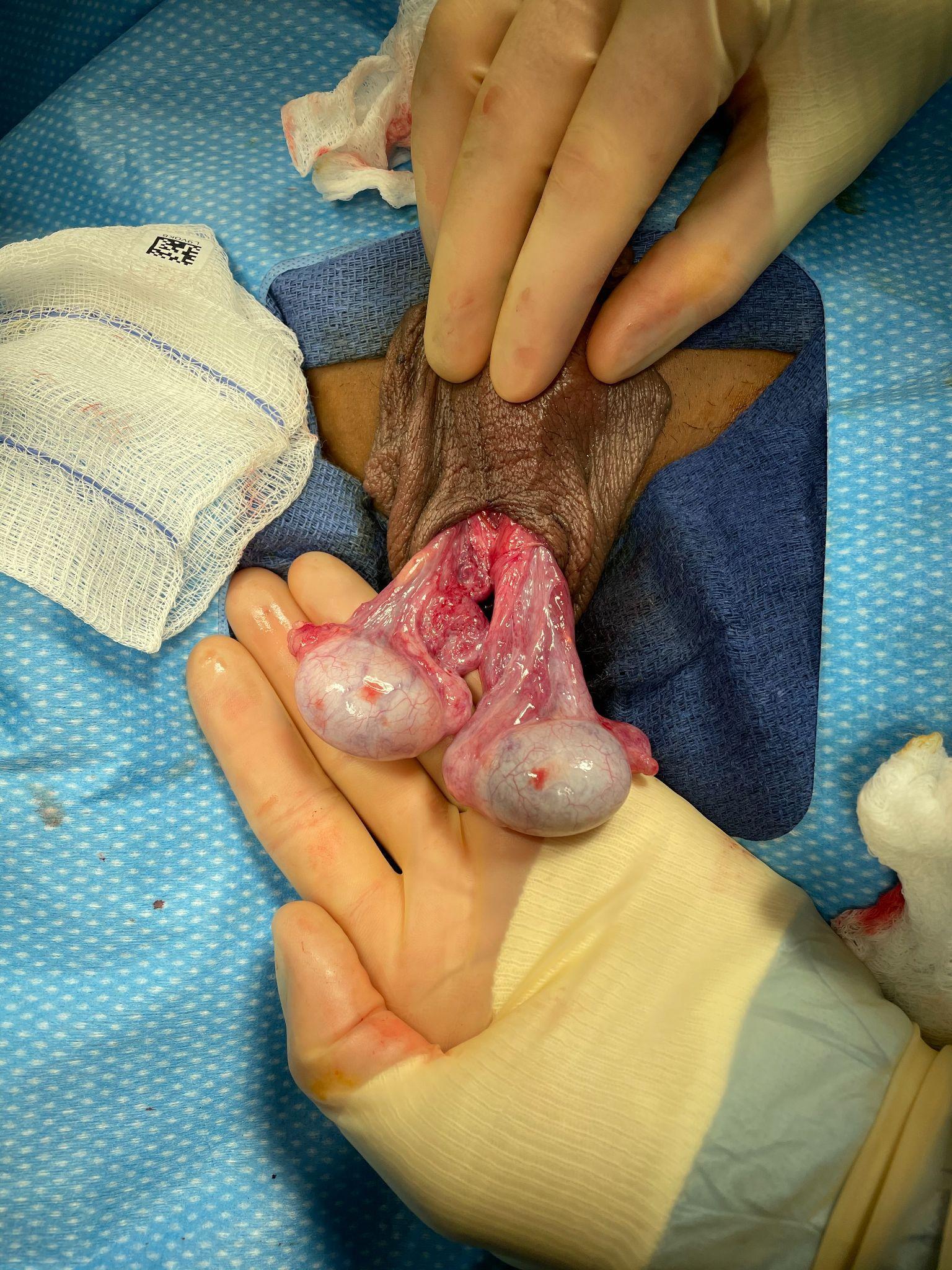

Figura 2 Deformidad en badajo de campana en un caso de torsión intravaginal (el testículo izquierdo ha sido detorsionado). Ninguno de los testículos presenta fusión de las hojas visceral y parietal de la túnica vaginal y, como resultado, la túnica vaginal se ha retraído hasta una posición alta sobre el cordón espermático y ambos testículos quedan colgando libremente, mostrando una disposición transversal con respecto al cordón espermático. Puede imaginarse que, si la hoja parietal de la túnica vaginal estuviera intacta, los testículos colgarían completamente dentro de la túnica vaginal, como el badajo de una campana.

Figura 3 Torsión intravaginal (izquierda) y torsión extravaginal (derecha). La túnica vaginal está resaltada en amarillo. En la torsión intravaginal, la torsión del cordón espermático ocurre por separado y dentro de la túnica vaginal. En la torsión extravaginal, el cordón espermático y la túnica vaginal se tuercen como una sola unidad.

Evaluación y diagnóstico de la torsión testicular en el recién nacido

La presentación de un neonato con TT extravaginal es variable, lo cual probablemente refleja el proceso de la enfermedad, así como las circunstancias que rodean el parto y los cuidados iniciales del neonato. Los recién nacidos pueden acumular edema en el periné durante el proceso del parto, y el escroto puede parecer particularmente aumentado de tamaño y eritematoso en las primeras horas tras el nacimiento. También puede haber un efecto de las hormonas maternas. Los hidroceles congénitos son frecuentes y pueden ser de mayor tamaño inmediatamente después del nacimiento. En conjunto, estos cambios pueden dificultar que los clínicos diferencien la anatomía específica del epidídimo y del testículo solo mediante la palpación.

La TT extravaginal en un neonato suele presentarse con un hemiescroto agrandado y endurecido. Los equipos de atención del parto y del periodo posnatal deben estar atentos a diferencias sutiles en el examen entre los respectivos hemiescrotos. El hemiescroto derecho e izquierdo deben inspeccionarse y palparse por separado, no como una unidad. Debe anotarse cualquier mayor firmeza de un lado, pérdida de las rugosidades escrotales o cambios cutáneos diferenciales, y esto debe motivar la repetición de los exámenes. Los hallazgos significativos en el examen inicial o los cambios en exámenes seriados deben motivar una consulta urológica urgente.

La torsión extravaginal observada en el momento del nacimiento es poco probable que sea salvable. En una revisión de la literatura, más del 90% de las torsiones neonatales consideradas “prenatales” o “posnatales” se sometieron a orquiectomía unilateral.14 Más importante que salvar el lado más obviamente afectado es el diagnóstico oportuno o la prevención de la torsión extravaginal asincrónica. Esto con frecuencia requiere exploración quirúrgica, ya que los hallazgos de una exploración escrotal unilateral pueden ser tan marcados que oculten los hallazgos del lado contralateral. Además, la CDUS es técnicamente difícil en un neonato, en particular en centros donde los ecografistas no están acostumbrados a obtener imágenes de recién nacidos. La exploración urgente del escroto neonatal en contextos de sospecha de torsión extravaginal neonatal unilateral es controvertida. La decisión de explorar quirúrgicamente el escroto de un niño recién nacido en el contexto de un examen unilateral sugestivo de torsión extravaginal contrapone la improbable posibilidad de salvar el testículo afectado y los riesgos anestésicos para el recién nacido frente a las consecuencias poco frecuentes pero devastadoras de una TT extravaginal asincrónica. Abundan en la literatura los reportes de casos de torsión extravaginal bilateral asincrónica. Publicaciones recientes han intentado cuantificar el riesgo de torsión asincrónica para el neonato. Una revisión de la literatura que abarcó 152 estudios con 1336 pacientes informó que el 11.8% de todos los eventos de torsión neonatal fueron asincrónicos, con una mediana de tiempo hasta la segunda torsión de 1 día. Los autores calcularon un número necesario para tratar (p. ej., explorar quirúrgicamente) para evitar la orquiectomía bilateral de 1.6, y el número necesario para tratar para evitar la atrofia testicular solitaria de 2.6. Una revisión de expedientes de 20 años de una sola institución informó un 3% de riesgo de torsión perinatal bilateral asincrónica.15 Dada la mayor seguridad de la anestesia perinatal en las últimas décadas, en opinión de los autores deberían considerarse los beneficios de una exploración quirúrgica temprana y urgente en el contexto de la torsión perinatal unilateral.

Evaluación y diagnóstico en el niño mayor

En cualquier paciente que se presente con dolor escrotal de inicio agudo, debe confirmarse o descartarse de inmediato un diagnóstico de TT. Es el diagnóstico que representa la amenaza más sensible al tiempo para el órgano. Los clínicos deben tener en cuenta que una anamnesis dirigida y un examen físico son los únicos requisitos previos para la exploración quirúrgica. La CDUS puede confirmar el diagnóstico presuntivo de TT o descartar isquemia del órgano afectado. La presencia de flujo vascular en la CDUS no descarta la existencia de isquemia incipiente (ya que es probable que el drenaje venoso se reduzca antes del edema y la congestión vascular que limitan el flujo arterial), TT reciente o intermitente, o torsión incompleta o parcial. En esta última situación, el cordón espermático puede rotar sobre su eje lo suficiente como para causar compromiso vascular, pero no lo bastante como para provocar una interrupción brusca del flujo sanguíneo.

Historia

La presentación clásica de la TT intravaginal consiste en el inicio súbito de dolor testicular en un varón peripuberal. Los pacientes o sus padres suelen describir un inicio súbito de dolor intenso. El dolor puede comenzar en reposo, y es común que los pacientes refieran despertarse del sueño con dolor súbito. Los pacientes pueden referir dolor tras un traumatismo escrotal. En este último contexto, se plantea la hipótesis de que el traumatismo en sí es poco probable que sea la causa de la TT, sino más bien un evento mal recordado o no relacionado. De hecho, los antecedentes de traumatismo genital reciente se han identificado como una causa de diagnóstico erróneo y del consecuente retraso en el tratamiento.2

Los síntomas asociados comunes pueden incluir dolor abdominal, náuseas y vómitos.16 Es importante destacar que el dolor abdominal y/o las náuseas con o sin emesis pueden preceder el inicio del dolor testicular. Esto crea un enigma diagnóstico con consecuencias potencialmente perjudiciales para los clínicos que enfocan su examen en el abdomen y omiten un examen genitourinario. El dolor abdominal aislado se ha demostrado que se asocia de manera significativa con presentaciones tardías (>24 horas) y mayores tasas de orquiectomía.2

La presencia de síntomas asociados puede ser útil para priorizar los diagnósticos diferenciales, ya que la torsión del apéndice testicular o del apéndice del epidídimo y la epididimitis u orquitis tienen más probabilidad de presentarse como dolor escrotal aislado. Los pacientes rara vez refieren disuria o un inicio gradual del dolor. Estos síntomas deben llevar a los clínicos a considerar otros diagnósticos, como epididimitis (estéril o bacteriana), orquitis o infección del tracto urinario.

Examen físico

Se debe realizar un examen abdominal y genitourinario. La piel escrotal puede revelar eritema, induración o calor. A menudo se observa un hidrocele tenso con disminución de la presencia de pliegues escrotales. En aquellos con piel clara que se presentan de manera tardía, un hidrocele tenso con una tonalidad violácea puede reflejar un testículo necrótico y/o un hematocele. Se ha demostrado que tales cambios cutáneos son predictivos de TT.17

Un reflejo cremastérico anormal sugiere una mayor probabilidad de TT.17,18 Sin embargo, la presencia de un reflejo cremastérico normal no puede descartar suficientemente un diagnóstico de TT.19 Del mismo modo, la ausencia de un reflejo cremastérico no es altamente específica para el diagnóstico. Al evaluar los reflejos cremastéricos, los profesionales deberían examinar primero el lado contralateral, ya que la ausencia de un reflejo ipsilateral solo es clínicamente relevante en presencia de un reflejo contralateral. Los clínicos pueden encontrar que el testículo afectado tiene una posición horizontal (deformidad en badajo de campana) o una posición “alta” (debido a que el cordón espermático torcido eleva el testículo hacia el canal inguinal).

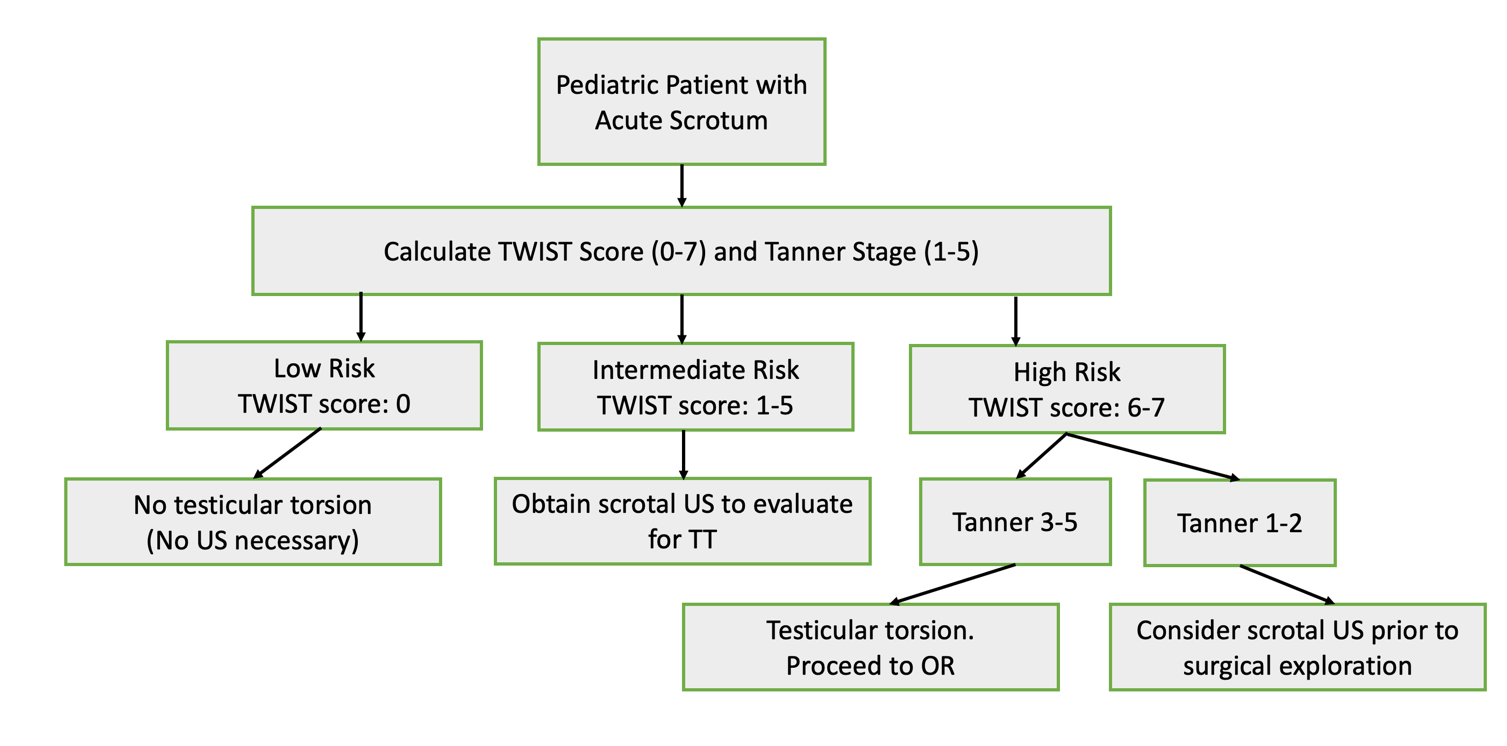

El uso del puntaje TWIST (introducido en 2013 por Barbosa et al) puede permitir a los clínicos estratificar el riesgo de los pacientes en bajo, intermedio y alto para TT basándose únicamente en el examen físico. Se calcula un puntaje total de 0-7 tras determinar la presencia de 5 síntomas: testículo duro (2 puntos), tumefacción testicular,2 reflejo cremastérico ausente,1 náuseas/vómitos,1 y testículo en posición alta.120 Según el algoritmo del puntaje, los pacientes de alto riesgo (puntaje ≥5) tienen un valor predictivo positivo del 100% para TT, por lo que los clínicos pueden considerar proceder directamente a la exploración quirúrgica, ya que el beneficio de la CDUS es mínimo. Los pacientes de bajo riesgo (≤2) tienen un valor predictivo negativo del 100% para TT, por lo que no requieren CDUS para descartar torsión. Los pacientes de riesgo intermedio pueden beneficiarse de la CDUS para confirmar el diagnóstico. Un estudio que evaluó la utilidad del puntaje TWIST entre proveedores no médicos y no urológicos determinó un PPV de 93.5% y un NPV de 100% cuando el alto riesgo se definió como un puntaje mayor que 6, el riesgo intermedio como 1-5, y el bajo riesgo como 0.21 (Figura 4)

Tabla 1 La puntuación TWIST y los grupos de estratificación del riesgo. Adaptado de Barbosa 2013

| Síntoma | Puntos otorgados |

|---|---|

| Testículo duro | 2 |

| Tumefacción testicular | 2 |

| Reflejo cremastérico ausente | 1 |

| Testículo en posición alta | 1 |

| Náuseas y/o vómitos | 1 |

| Total | |

| Alto riesgo | ≥5 |

| Riesgo intermedio | 3-4 |

| Bajo riesgo | ≤2 |

Figura 4 Diagrama de flujo con el manejo propuesto de la torsión testicular, adaptado de Sheth 2016. Cabe destacar que este estudio evaluó la utilidad del puntaje TWIST entre proveedores que no son urólogos ni médicos (para reflejar al personal de triaje del servicio de urgencias) y utiliza umbrales diferentes para los puntajes de bajo, intermedio y alto riesgo que los de la descripción original de Barbosa et al. 2013

Pruebas iniciales

El análisis de orina (UA) es una prueba rápida y de bajo costo útil en el contexto de dolor escrotal agudo. Puede ayudar a diferenciar la TT de la epididimitis bacteriana o de la infección del tracto urinario, en ambas se esperaría que el UA demostrara piuria. En la TT, se esperaría que el UA fuera normal.

Estudios de imagen

El uso rutinario es controvertido, y abundan los estudios que evalúan la exactitud y la utilidad de las pruebas de imagen.22,23,24 Si el diagnóstico de TT es equívoco sobre la base de la historia clínica y el examen físico recabados, entonces se puede recurrir a las pruebas de imagen. Sin embargo, las pruebas de imagen no deben utilizarse como sustituto de una historia clínica y un examen físico adecuados. Las pruebas de imagen innecesarias pueden retrasar la cirugía e incrementar el costo de la atención. Las pruebas de imagen no son necesarias para diagnosticar TT.

Ecografía Doppler en color

El CDUS es útil para la visualización de la anatomía testicular, incluyendo la arquitectura del cordón espermático, el flujo sanguíneo testicular y la ecotextura testicular. La disminución o ausencia de flujo sanguíneo testicular en la ecografía tiene una especificidad del 99% y una sensibilidad del 63% para la TT.24 Como regla general, las imágenes deben compararse siempre con el lado contralateral no afectado. En la TT, el testículo afectado puede parecer edematoso y aumentado de tamaño. En los casos de CDUS equívoco, los clínicos deben prestar especial atención a los volúmenes testiculares comparativos, ya que esto puede ser una pista para el diagnóstico. También puede estar presente un hidrocele reactivo.25 Una ecotextura heterogénea en el contexto de ausencia de señal Doppler probablemente indica el inicio de la necrosis coagulativa de un testículo no viable.

Ocasionalmente, se visualiza un flujo arterial normal o aumentado en un paciente con TT, generando un resultado falso negativo engañoso. Un estudio multicéntrico demostró que el 24% de sus torsiones confirmadas del cordón espermático presentaban flujo testicular normal o aumentado en la CDUS preoperatoria.26 Desde el punto de vista conceptual, se ha postulado que, a medida que el cordón espermático se tuerce, el drenaje venoso del testículo probablemente se afecta antes que el aporte arterial. Por lo tanto, un flujo arterial disminuido o mantenido puede anunciar el inicio de isquemia testicular y no debe considerarse necesariamente tranquilizador en el contexto de ausencia o disminución del drenaje venoso. La disminución del flujo sanguíneo puede ser sugestiva de torsión parcial o incompleta y de torsión intermitente del cordón espermático. Debe destacarse que la medición Doppler y de la onda vascular depende en gran medida del ecografista y es sustancialmente más difícil de obtener en bebés y niños pequeños. Ante antecedentes, examen físico y hallazgos en la CDUS discordantes, los clínicos deben mantener un alto índice de sospecha de TT parcial o intermitente.

Ultrasonografía de alta resolución

la ultrasonografía de alta resolución (HRUS) es un método de imagen más sensible (97.3%) y específico (99%) en comparación con CDUS.26 Permite la visualización directa de un cordón espermático torsionado. Los estudios han demostrado que ecografistas y radiólogos bien entrenados pueden identificar con precisión la tortuosidad en el cordón espermático mediante los llamados signos del cordón espermático en “forma de caracol” o de “remolino”. Existe controversia en la literatura sobre la utilidad de la identificación por HRUS de los signos de “remolino” del cordón espermático. Cuando se diagnostican correctamente en el contexto de un flujo sanguíneo testicular anómalo, estas anomalías del cordón espermático pueden constituir evidencia definitiva de torsión intravaginal en curso. Sin embargo, una crítica común a las anomalías del cordón espermático identificadas por HRUS es que la literatura que resalta estas anomalías no ha logrado identificar el denominador de casos ni cuántos niños con torsión no presentan cambios identificables del cordón espermático en la TT. En otras palabras, la ausencia de signos identificados o reportados de tortuosidad del cordón espermático no debe descartar el diagnóstico de TT, y los clínicos no deben utilizar los hallazgos en HRUS del cordón espermático por sí solos como indicación para la exploración.

Gammagrafía nuclear

Esta prueba utiliza pertecnetato de tecnecio-99m intravenoso para evaluar la perfusión testicular. Antes de la CDUS, la gammagrafía era la prueba de imagen de elección para la sospecha de TT. Los estudios han reportado una sensibilidad y especificidad similares a las de la CDUS.27,28 Sin embargo, la exploración puede tardar varias horas en realizarse, no siempre está disponible de forma inmediata y conlleva el riesgo de prolongar el tiempo de isquemia testicular. Por estos motivos, la gammagrafía rara vez se utiliza en el diagnóstico moderno de la TT.

Opciones de tratamiento

TT requiere corrección quirúrgica urgente. Tanto el tiempo transcurrido desde el inicio del dolor (conceptualizado como equivalente al tiempo de isquemia testicular) como el grado de torsión del cordón espermático impactan directamente las tasas de salvamento testicular.29,30 Como regla general, el testículo es más probable que sea viable (>90% de probabilidad) si la exploración escrotal se realiza dentro de las primeras 6 horas desde el inicio de los síntomas. Después de la ventana inicial de 6 horas, el testículo puede seguir siendo viable, pero a tasas que disminuyen de forma precipitada, lo que resalta la importancia de una intervención oportuna.31 Sin embargo, incluso dentro de este periodo, los pacientes pueden presentar cierto grado de atrofia testicular posoperatoria debido al daño por isquemia.

Detorsión manual

La detorsión manual, o rotación a pie de cama del testículo dentro del escroto, es una opción para el manejo inicial mientras se espera la consulta urológica y el tratamiento quirúrgico urgente o el traslado a otro centro. La maniobra puede restablecer algo de flujo sanguíneo al testículo y mejorar las probabilidades de viabilidad testicular en el momento de la exploración.32,33 La detorsión manual no elimina la necesidad de cirugía y no debe retrasar la intervención quirúrgica.

La enseñanza clásica en la detorsión manual de la TT es que el testículo se tuerce alrededor del cordón espermático en una dirección lateral a medial. Los pasos para lograr la detorsión manual indican al clínico deshacer el cordón espermático en la dirección opuesta: de medial a lateral. El movimiento de rotar el testículo alejándolo de la línea media es lo que comúnmente se denomina “abrir el libro”. El clínico debe sujetar el testículo afectado entre el pulgar y el índice y rotar suavemente el testículo dentro del escroto hacia afuera en dirección al muslo para un giro completo de 360 grados. La detorsión manual exitosa suele sugerirse por el alivio inmediato del dolor y el retorno del flujo arterial en CDUS. Pueden ser necesarias múltiples rotaciones dependiendo de cuántas vueltas tenga el cordón. En un escenario ideal, la ecografía a pie de cama o CDUS puede utilizarse para demostrar objetivamente la mejoría del flujo sanguíneo. Si no se logra el alivio del dolor o este empeora al detorsionar manualmente el testículo alejándolo de la línea media, podría intentarse la detorsión mediante una rotación hacia adentro (medial).

Contrario a esta enseñanza clásica, estudios retrospectivos demostraron que al menos un tercio de sus casos de TT ocurrió en sentido lateral.29,34 Por lo tanto, aunque la técnica de “abrir el libro” probablemente reduzca la torsión del cordón espermático y potencialmente restablezca el flujo sanguíneo en la mayoría de los casos, los clínicos que intenten la detorsión manual deben estar atentos a la posibilidad de una detorsión incompleta de un cordón espermático con varias vueltas o de un aumento de los grados de rotación, lo cual, en este último caso, puede empeorar el grado de isquemia. Por lo tanto, en opinión de los autores, no debe intentarse la detorsión manual si la intervención quirúrgica está fácilmente disponible. Además, no debe intentarse la detorsión manual si el diagnóstico es dudoso o si la maniobra retrasará la intervención quirúrgica definitiva. Si los clínicos que realizan la detorsión manual no son quienes brindarán la intervención quirúrgica definitiva, es vital comunicar que la maniobra se intentó y su resultado.

Corrección quirúrgica

El manejo quirúrgico consiste en destorsión y orquiopexia (fijación del testículo a la pared escrotal declive) u orquiectomía del testículo afectado, según la viabilidad del órgano al examinarlo intraoperatoriamente. En cualquiera de los casos, la orquiopexia del testículo contralateral es el estándar de atención debido a la alta probabilidad de una deformidad en badajo de campana contralateral.

Descripción general de la técnica quirúrgica:

Una incisión en el rafe medio o incisiones horizontales bilaterales son las más comunes. Una incisión en el rafe medio permite explorar cada hemiescroto a través de una única incisión.

- Incisión escrotal en la línea media

- Disección con electrocirugía a través de la fascia de Dartos y hacia el hemiescroto afectado

- Exteriorización de la túnica vaginal a través de la incisión en la fascia de Dartos

- (Inspección de la túnica vaginal y del cordón espermático para detectar torsión extravaginal en casos de torsión neonatal)

- Incisión y eversión de la túnica vaginal para permitir la exteriorización e inspección del testículo y el epidídimo afectados. Nótese la presencia de torsión intravaginal del cordón espermático y el color del testículo y el epidídimo

- Destorsión del cordón espermático y del testículo, anotando la dirección y los grados de torsión

- Envolver el testículo destorcido en una compresa de gasa tibia

- Realizar la misma disección con electrocirugía de la fascia de Dartos en el hemiescroto contralateral para exponer la túnica vaginal y el testículo contralaterales

- Incisión y eversión de la túnica vaginal para permitir la exteriorización e inspección del testículo y el epidídimo contralaterales. Nótese la presencia de una deformidad en badajo de campana

- Volver al testículo destorcido y repetir la inspección para determinar la viabilidad. Si es obviamente no viable, realizar una orquiectomía. Si es viable, realizar una orquidopexia. Esta es una evaluación subjetiva y a menudo variable entre profesionales. Si la viabilidad parece indeterminada, los profesionales pueden optar por realizar una evaluación con micro-Doppler del testículo para buscar flujo arterial o incidir el testículo con una incisión ecuatorial para identificar sangrado y túbulos seminíferos de aspecto sano secundarios a la liberación de la presión del síndrome compartimental. En el caso en que una fasciotomía ecuatorial de la túnica vaginal produzca sangrado de la túnica vaginal, túbulos seminíferos de aspecto sano y una mejoría global del color del testículo, se ha descrito el aumento de la túnica albugínea con un parche de túnica vaginal.35 (Video 1)

- Un testículo afectado que se ha determinado viable y el testículo contralateral normal deben fijarse en el escroto para prevenir una torsión futura. Los testículos deben fijarse con 3 puntos de fijación, ya sea entre sí (a través del tabique escrotal, como en una técnica de “septopexia”) o en posición declive en su respectivo hemiescroto. Los autores usan una sutura de polipropileno 5-0 (no absorbible)

- Cerrar la(s) incisión(es) escrotal(es) de manera habitual. En los casos en que se realiza una orquiectomía en el contexto de una torsión testicular de larga evolución y presentación tardía con edema sustancial, puede dejarse un drenaje escrotal para ayudar a prevenir infección, hematocele o formación de hidrocele

[Video 1](#video-1){:.video-link}. Manejo intraoperatorio de la torsión testicular. En este caso, la corrección quirúrgica incluyó la confección de un colgajo de la túnica vaginal. Nota: Este video fue creado para y presentado en la videoteca educativa del plan de estudios básico de la American Urological Association.

Seguimiento sugerido

Los pacientes que se someten a manejo quirúrgico de la torsión testicular deben ser evaluados al menos una vez en consulta externa de seguimiento para verificar la adecuada cicatrización de la herida y un examen físico sin hallazgos preocupantes. Tras la detorsión testicular y la orquiopexia intentadas por TT, los clínicos deben documentar el tamaño de los testículos y la presencia o ausencia de atrofia en el testículo afectado. El término “rescate testicular” debe reservarse preferentemente para los testículos afectados que han mostrado volumen conservado en el seguimiento.

Durante el seguimiento, los autores suelen tratar los siguientes temas con los pacientes y sus familias:

- En el contexto de una orquidopexia de un testículo afectado, la apariencia y el flujo vascular hacia el testículo afectado en caso de que el paciente alguna vez reciba otro CDUS por otra razón

- En el contexto de una orquiectomía de un testículo afectado, existe la posibilidad de una prótesis testicular tras la finalización de la pubertad

- Aunque la torsión testicular recurrente es teóricamente imposible, los pacientes pueden sentir dolor o presentar anomalías por otras razones. Los pacientes pueden beneficiarse de autoexámenes mensuales y deben alertar a sus padres o a sus médicos de inmediato si sienten dolor o palpan algo diferente

- A todos los pacientes, especialmente a aquellos que se han sometido a orquiectomía por TT y ahora tienen un testículo solitario, se les debe recomendar usar un protector genital deportivo durante deportes y actividades recreativas potencialmente de contacto. Existen protectores genitales deportivos modernos de perfil delgado que se ajustan a pantalones cortos de compresión y pantalones deslizantes cómodos

Torsión de los apéndices testiculares

El testículo y el epidídimo con frecuencia tienen un pequeño apéndice asociado en su polo superior. El apéndice testicular es un remanente embrionario del conducto paramesonéfrico. El apéndice del epidídimo es un remanente embrionario del sistema del conducto mesonéfrico. Cualquiera de estas estructuras puede retorcerse sobre su eje, de manera muy similar a como el cordón espermático se retuerce en la TT intravaginal, lo que conduce a isquemia y eventual necrosis. La presentación puede imitar la TT con inicio súbito de dolor y tumefacción escrotales. Sin embargo, existen algunos hallazgos negativos pertinentes clave en la historia clínica y el examen físico que los autores han observado anecdóticamente al comparar la torsión de los apéndices testiculares con la TT:

- Los pacientes con torsión de los apéndices testiculares tienen menos probabilidades de referir náuseas y vómitos. Esto probablemente sea secundario a la falta de sensación visceral por la isquemia de los apéndices testiculares en comparación con la isquemia testicular

- Los pacientes con torsión de los apéndices testiculares no suelen presentar un testículo en posición elevada dentro del escroto

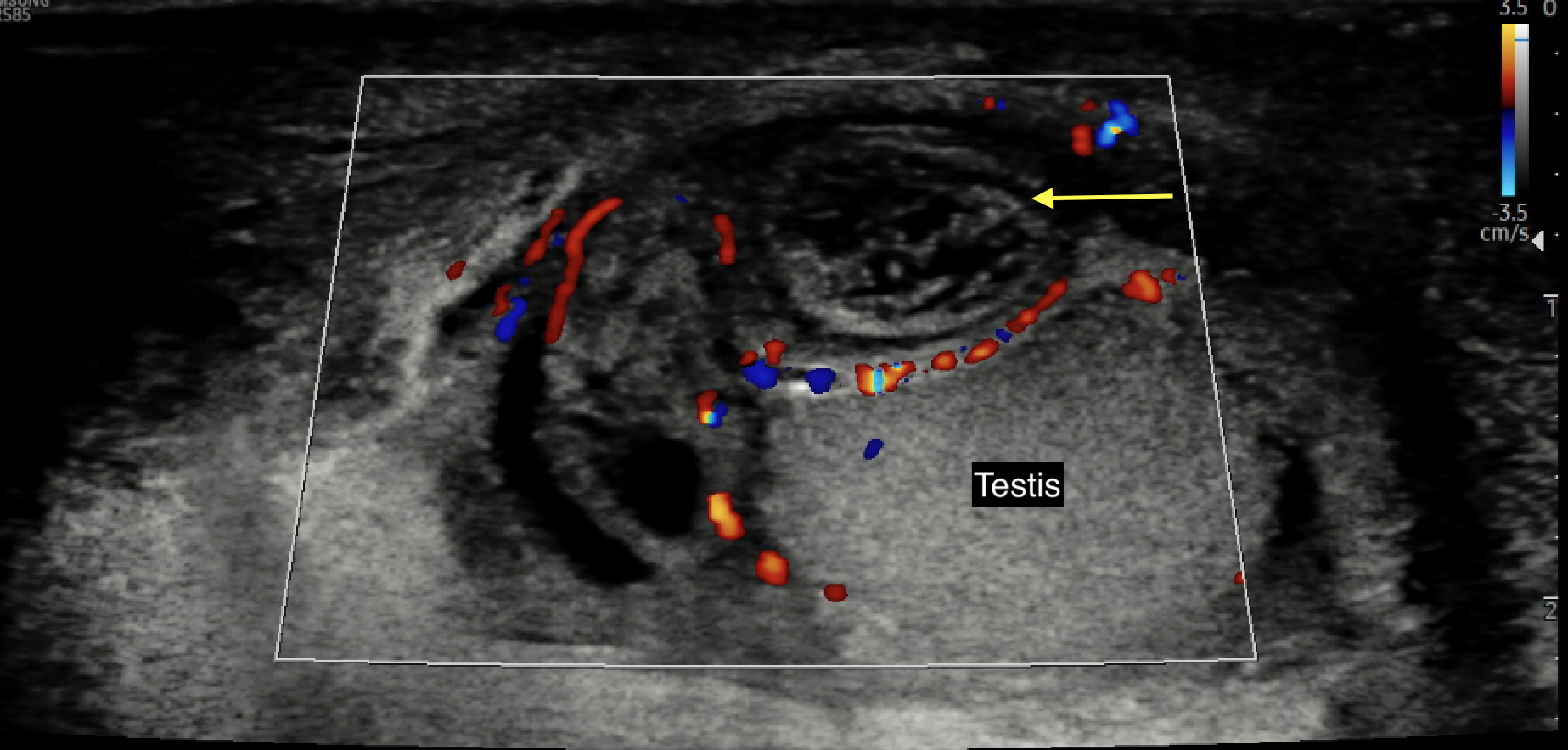

- Los pacientes con torsión de los apéndices testiculares a menudo presentan buen flujo testicular en el CDUS, con hallazgos característicos de una pequeña estructura heterogénea y avascular, adyacente y separada del testículo36 (Véase Figura 5 para una imagen representativa de la colección de los autores)

Figura 5 Imagen de ecografía Doppler en color de un apéndice testicular o epidídimo torsionado, avascular, edematoso y de aspecto heterogéneo (flecha amarilla)

En el examen físico, la torsión del apéndice testicular se presentará con un hemiescroto hinchado y doloroso. El testículo parecerá tener una posición normal y dependiente. En individuos de piel clara, ocasionalmente puede identificarse el “punto azul” en la pared escrotal lateral, correspondiente a la apariencia del apéndice isquémico a través de una piel escrotal adelgazada por un saco de hidrocele translúcido. En los pacientes que toleran un examen minucioso, este punto corresponderá a dolor focal a la palpación. Nótese que el signo del punto azul se ha reportado en tan solo el 10% de los casos de torsión del apéndice testicular y será difícil de identificar en pacientes de piel oscura.

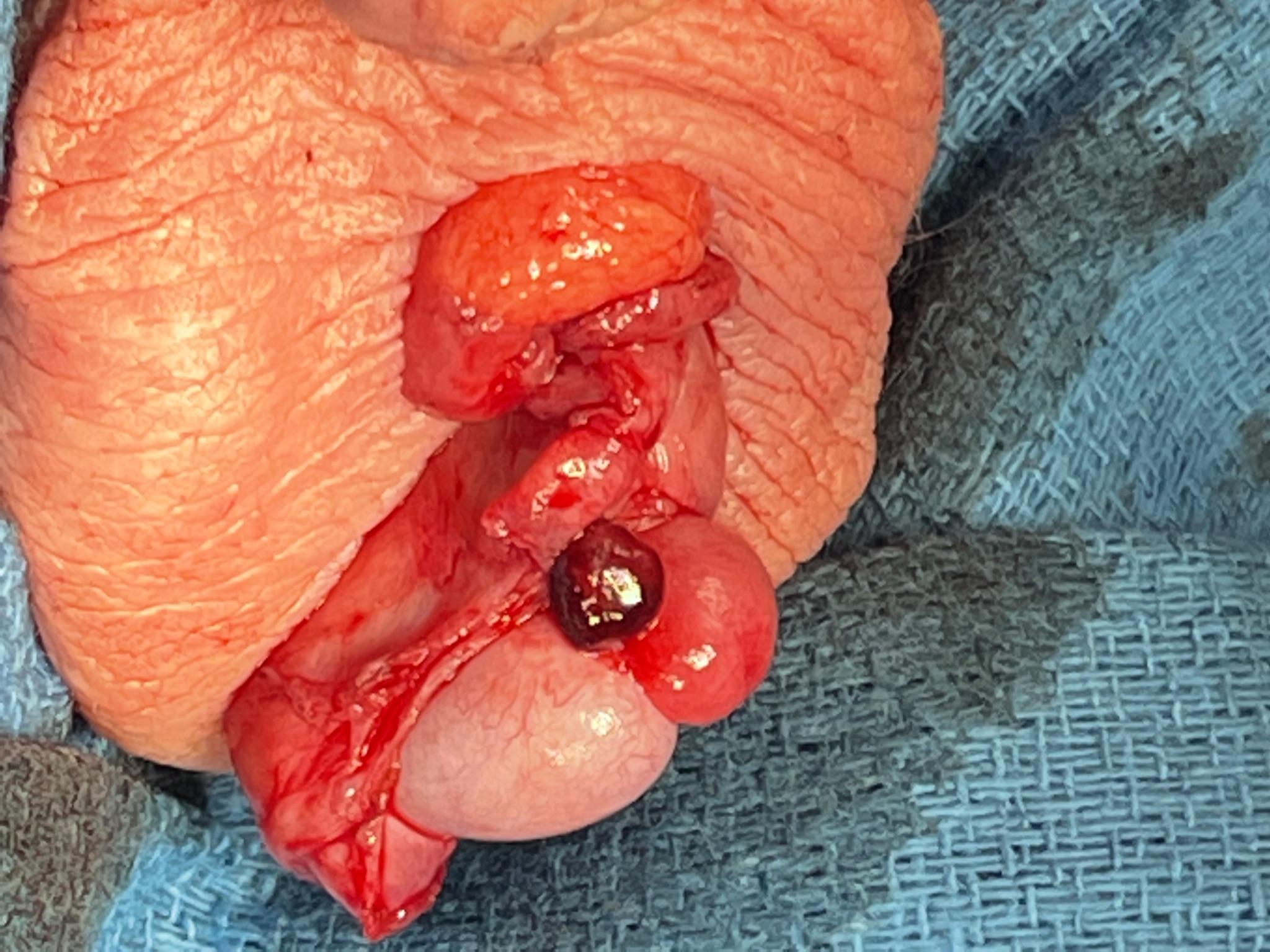

Si el diagnóstico está en duda o no se puede descartar la isquemia testicular, se recomienda la exploración quirúrgica. En la exploración, el cirujano encontrará un apéndice torsionado con un testículo y un epidídimo por lo demás de aspecto normal (Figura 6 y Figura 7). El apéndice anexial puede extirparse quirúrgicamente y se cierra el escroto. Para los casos en los que se confirma un buen flujo testicular, los antecedentes y los datos objetivos son inconsistentes con TT, y la torsión anexial es probable, se puede diferir la exploración quirúrgica.

El tratamiento de la torsión de los apéndices testiculares es conservador e incluye reposo, aplicación periódica de hielo en el periodo agudo, elevación escrotal y medicamentos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos. Los autores han solicitado de forma sistemática una ecografía escrotal de control en el plazo de una semana si persiste el dolor para confirmar el diagnóstico y a las 4–6 semanas tras la resolución del dolor para documentar que la masa de los apéndices testiculares observada en la ecografía escrotal inicial ha involucionado.

Figura 6 Pinzas sujetando un apéndice del epidídimo torsionado

Figura 7 Aspecto de un apéndice epididimario ingurgitado durante la exploración escrotal en lo que se consideró un examen equívoco para TT

Epididimitis

Epidemiología

La epididimitis es la inflamación del epidídimo: la estructura tubular enrollada que se sitúa posterior y superiormente sobre el testículo de forma ovalada. El epidídimo tiene la función de transportar y madurar los espermatozoides procedentes del testículo. En los adolescentes, la epididimitis representa el 35-71% de los casos de dolor escrotal agudo.37 Aunque la afección ocurre con mayor frecuencia en adolescentes mayores sexualmente activos, también puede presentarse en pacientes más jóvenes secundaria a infección viral o a inflamación química (de orina).

Patogénesis

En pacientes de mayor edad, la epididimitis se presenta con mayor frecuencia debido a una infección bacteriana. Por lo general, la causante es una infección de transmisión sexual (ITS), especialmente en hombres más jóvenes, lo que ocasiona la migración de bacterias desde la uretra hacia el conducto deferente y el epidídimo. Neisseria gonorrhea y Chlamydia trachomatis son los agentes infecciosos más frecuentes en esta población. De manera similar, la orina infectada por una infección del tracto urinario puede refluir hacia el conducto deferente y causar epididimitis. Esto puede ser precipitado por levantar objetos pesados.

En los niños más pequeños, la causa más común de epididimitis es estéril y secundaria a la micción a presión de orina “estéril” hacia los conductos eyaculadores y de regreso a través del conducto deferente hasta el epidídimo (la llamada epididimitis “estéril” o “química”). Las etiologías menos frecuentes son secundarias a infecciones virales (p. ej., por virus identificados, como en la orquitis por parotiditis secundaria a un virus de la familia Paramyxoviridae, o por virus no identificados), traumatismo y tuberculosis.

Evaluación y diagnóstico

El diagnóstico de la epididimitis es clínico y a menudo de exclusión. Un paciente que se presenta con inicio gradual de dolor escrotal, tumefacción escrotal y (posiblemente) fiebre debe suscitar un alto índice de sospecha de epididimitis. El paciente también puede referir síntomas de disuria, polaquiuria, urgencia miccional, incontinencia y/o secreción uretral. En niños pequeños en quienes se sospecha epididimitis química, debe recabarse una historia detallada de los hábitos miccionales y del estreñimiento. Con frecuencia, los padres refieren que estos niños retienen la orina durante períodos prolongados, seguidos de urgencia miccional. El estreñimiento puede llevar a los niños tanto a una micción a presión como a una defecación a presión, ambas pueden favorecer un reflujo de orina a presión hacia el conducto eyaculador y el conducto deferente.

El examen físico debe revelar una posición normal y vertical del testículo, reflejo cremastérico normal, y alivio del dolor con la elevación del testículo (signo de Prehn). La palpación del epidídimo en la cara posterior del testículo provocará dolor a la palpación.

La evaluación debe incluir análisis de orina y urocultivo. En pacientes mayores con antecedentes o examen preocupantes, puede ser necesario un CDUS para descartar TT y otras patologías, desde rotura testicular hasta abscesos escrotales. En niños más pequeños en quienes se espera epididimitis química, 1) una ecografía vesical que evalúe la distensión vesical y/o un residuo posmiccional elevado, y 2) una radiografía simple de abdomen que evalúe el estreñimiento, pueden respaldar el diagnóstico.

Tratamiento

El tratamiento es variable y depende de la causa de la epididimitis. El tratamiento principal para la epididimitis causada por ITS es el uso de antimicrobianos adecuados. Se deben administrar ceftriaxona y doxiciclina para tratar N. gonorrhea y C. trachomatis. La azitromicina puede sustituir a la doxiciclina en pacientes con alergia o contraindicación. La atención de apoyo adicional incluye analgésicos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos y soporte escrotal. También se debe evaluar y tratar a las parejas con antibióticos. El tratamiento de la epididimitis química en un niño pequeño incluye cuidados de apoyo con analgésicos antiinflamatorios no esteroideos administrados de forma programada y ropa interior de soporte. La retención voluntaria de orina, la micción a presión y el estreñimiento deben abordarse de manera concomitante.

Conclusión

En resumen, un “escroto agudo” es el término clínico para la aparición rápida de un escroto doloroso o tumefacto. El diagnóstico diferencial incluye, entre otros, la torsión testicular, la torsión del apéndice testicular y la epididimitis. La torsión testicular debe descartarse antes de iniciar el estudio de etiologías alternativas.

Puntos clave

- La incidencia de la torsión testicular (TT) tiene una distribución bimodal: el primer año de vida (~1 mes de edad), cuando la torsión es más probable que sea extravaginal, y el período puberal (~12 años de edad), cuando la torsión es más probable que sea intravaginal

- La deformidad en badajo es el principal factor de riesgo que predispone a la torsión intravaginal

- La TT es un diagnóstico clínico: una anamnesis dirigida y un examen físico son los únicos prerrequisitos para la exploración quirúrgica

- En casos con hallazgos clínicos equívocos, puede utilizarse la ecografía Doppler color (CDUS) para confirmar isquemia del órgano afectado

- La presencia de flujo vascular en la CDUS no necesariamente descarta la presencia de isquemia en desarrollo

- No deben realizarse pruebas de imagen si retrasan de forma significativa la exploración quirúrgica y el tratamiento definitivo

- Tenga cuidado con el dolor abdominal aislado y recuerde realizar un examen genitourinario. Se ha demostrado que el dolor abdominal aislado como único motivo de consulta en un niño varón se asocia de manera significativa con presentaciones tardías (>24 horas) y mayores tasas de orquiectomía

Referencias

- Jefferies MT, Cox AC, Gupta A, Proctor A. The management of acute testicular pain in children and adolescents. Bmj 2015; 350 (apr02 5): h1563–h1563. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.h1563.

- Bayne CE, Villanueva J, Davis TD, Pohl HG, Rushton HG. Factors Associated with Delayed Presentation and Misdiagnosis of Testicular Torsion: A Case-Control Study. J Pediatr 2017; 186: 200–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.03.037.

- McCombe AW, Scobie WG. Torsion of Scrotal Contents in Children. J Urol 1988; 140 (1): 214–214. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41551-5.

- Kadish HA, Bolte RG. A Retrospective Review of Pediatric Patients With Epididymitis, Testicular Torsion, and Torsion of Testicular Appendages. Pediatrics 1998; 102 (1): 73–76. DOI: 10.1542/peds.102.1.73.

- Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. The Incidence of the Cremasteric Reflex in Normal Boys. J Urol 1994; 152 (2 Part 2): 779–780. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32707-6.

- Bingöl-Koloğlu M, Tanyel FC, Anlar B, Büyükpamukçu N. Cremasteric reflex and retraction of a testis. J Pediatr Surg 2001; 36 (6): 863–867. DOI: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.23956.

- Williamson RCN. Torsion of the testis and allied conditions. Br J Surg 1976; 63 (6): 465–476. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800630618.

- Zhao LC, Lautz TB, Meeks JJ, Maizels M. Pediatric Testicular Torsion Epidemiology Using a National Database: Incidence, Risk of Orchiectomy and Possible Measures Toward Improving the Quality of Care. J Urol 2011; 186 (5): 2009–2013. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.024.

- Mano R, Livne PM, Nevo A, Sivan B, Ben-Meir D. Testicular Torsion in the First Year of Life – Characteristics and Treatment Outcome. Urology 2013; 82 (5): 1132–1137. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.07.018.

- Mathews John C, Kooner G, Mathew DE, Ahmed S, Kenny SE. Neonatal testicular torsion – a lost cause? Acta Paediatr 2008; 97 (4): 502–504. DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00701.x.

- Taghavi K, Dumble C, Hutson JM, Mushtaq I, Mirjalili SA. The bell-clapper deformity of the testis: The definitive pathological anatomy. J Pediatr Surg 2021; 56 (8): 1405–1410. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2020.06.023.

- Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformityin an autopsy series. Urology 1994; 44 (1): 114–116. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(94)80020-0.

- Martin AD, Rushton HG. The Prevalence of Bell Clapper Anomaly in the Solitary Testis in Cases of Prior Perinatal Torsion. J Urol 2014; 191 (5s): 1573–1577. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.013.

- O’Kelly F, Chua M, Erlich T, Patterson K, DeCotiis K, Koyle MA. Delaying Urgent Exploration in Neonatal Testicular Torsion May Have Significant Consequences for the Contralateral Testis: A Critical Literature Review. Urology 2021; 153: 277–284. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.10.064.

- Erlich T, Ghazzaoui AE, Pokarowski M, O’Kelly F, Lorenzo AJ, Bagli DJ, et al.. Perinatal testicular torsion: The clear cut, the controversial, and the "quiet" scenarios. J Pediatr Surg 2021; 57 (10): 288–297. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.10.003.

- Bayne CE, Hsieh MH. Testicular Torsion. In: Cabana MD, editor. The 5-minute Pediatric Consult. 8th. DOI: 10.1016/b978-0-323-47778-9.50163-x.

- Srinivasan A, Cinman N, Feber KM, Gitlin J, Palmer LS. Faculty Opinions recommendation of History and physical examination findings predictive of testicular torsion: an attempt to promote clinical diagnosis by house staff. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2011; 7: 470–474. DOI: 10.3410/f.11135959.12106058.

- Boettcher M, Bergholz R, Krebs TF, Wenke K, Aronson DC. Clinical Predictors of Testicular Torsion in Children. Urology 2012; 79 (3): 670–674. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.10.041.

- Beni-Israel T, Goldman M, Bar Chaim S, Kozer E. Clinical predictors for testicular torsion as seen in the pediatric ED. Am J Emerg Med 2010; 28 (7): 786–789. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.03.025.

- Barbosa JA, Tiseo BC, Barayan GA. Development and Initial Validation of a Scoring System to Diagnose Testicular Torsion in Children. Yearbook of Urology 2013; 2013: 6–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.yuro.2013.06.025.

- Sheth KR, Keays M, Grimsby GM, Granberg CF, Menon VS, DaJusta DG, et al.. Diagnosing Testicular Torsion before Urological Consultation and Imaging: Validation of the TWIST Score. J Urol 2016; 195 (6): 1870–1876. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.01.101.

- Jefferson RH, Perez LM, Joseph DB. Critical Analysis of the Clinical Presentation of Acute Scrotum: A 9-Year Experience at a Single Institution. J Urol 1997; 158 (3): 1198–1200. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64426-4.

- Friedman N, Pancer Z, Savic R, Tseng F, Lee MS, Mclean L, et al.. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound by pediatric emergency physicians for testicular torsion. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (6): 608.e1–608.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.07.003.

- Karmazyn B, Steinberg R, Kornreich L, Freud E, Grozovski S, Schwarz M, et al.. Clinical and sonographic criteria of acute scrotum in children: a retrospective study of 172 boys. Pediatr Radiol 2005; 35 (3): 302–310. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-004-1347-9.

- Bandarkar AN, Blask AR. Testicular torsion with preserved flow: key sonographic features and value-added approach to diagnosis. Pediatr Radiol 2018; 48 (5): 735–744. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-018-4093-0.

- Kalfa N, Veyrac C, Lopez M, Lopez C, Maurel A, Kaselas C, et al.. Multicenter Assessment of Ultrasound of the Spermatic Cord in Children With Acute Scrotum. J Urol 2007; 177 (1): 297–301. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.08.128.

- NUSSBAUM BLASK ANNAR, BULAS DOROTHY, SHALABY-RANA EGLAL, RUSHTON GIL, SHAO CHENG, MAJD MASSOUD. Color Doppler sonography and scintigraphy of the testis: A prospective, comparative analysis in children with acute scrotal pain. Pediatr Emerg Care 2002; 18 (2): 67–71. DOI: 10.1097/00006565-200204000-00001.

- Paltiel HJ, Connolly LP, Atala A, Paltiel AD, Zurakowski D, Treves ST. Acute Scrotal Symptoms in Boys With an Indeterminate Clinical Presentation: Comparison of Color Doppler Sonography and Scintigraphy. J Urol 1998; 161 (4): 1408–1408. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)61728-2.

- SESSIONS ANNETTEE, RABINOWITZ RONALD, HULBERT WILLIAMC, GOLDSTEIN MARTINM, MEVORACH ROBERTA. Testicular Torsion: Direction, Degree, Duration and Disinformation. J Urol 2003; 169: 663–665. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200302000-00059.

- Castañeda-Sánchez I, Tully B, Shipman M, Hoeft A, Hamby T, Palmer BW. Testicular torsion: A retrospective investigation of predictors of surgical outcomes and of remaining controversies. J Pediatr Urol 2017; 13 (5): 516.e1–516.e4. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.03.030.

- Mellick LB, Sinex JE, Gibson RW, Mears K. A Systematic Review of Testicle Survival Time After a Torsion Event. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019; Publish Ahead of Print: 821–825. DOI: 10.1097/pec.0000000000001287.

- Dias Filho AC, Oliveira Rodrigues R, Riccetto CLZ, Oliveira PG. Improving Organ Salvage in Testicular Torsion: Comparative Study of Patients Undergoing vs Not Undergoing Preoperative Manual Detorsion. J Urol 2017; 197 (3 Part 1): 811–817. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.09.087.

- Garel L, Dubois J, Azzie G, Filiatrault D, Grignon A, Yazbeck S. Preoperative manual detorsion of the spermatic cord with Doppler ultrasound monitoring in patients with intravaginal acute testicular torsion. Pediatr Radiol 2000; 30 (1): 41–44. DOI: 10.1007/s002470050012.

- Yecies T, Bandari J, Schneck F, Cannon G. Direction of Rotation in Testicular Torsion and Identification of Predictors of Testicular Salvage. Urology 2018; 114: 163–166. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.11.034.

- Kutikov A, Casale P, White MA, Meyer WA, Chang A, Gosalbez R, et al.. Testicular Compartment Syndrome: A New Approach to Conceptualizing and Managing Testicular Torsion. Urology 2008; 72 (4): 786–789. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.031.

- Lev M, Ramon J, Mor Y, Jacobson JM, Soudack M. Sonographic appearances of torsion of the appendix testis and appendix epididymis in children. J Clin Ultrasound 2015; 43 (8): 485–489. DOI: 10.1002/jcu.22265.

- Lehmann C, Biro FM, Slap GB. Chapter 20 - Testicular and Scrotal Disorders. Adolescent Medicine. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008.

Última actualización: 2025-09-21 13:35