51: Desarrollos futuros en el manejo de cálculos

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 20 minutos para leer.

Introducción

En las dos últimas décadas se ha observado un aumento drástico de la incidencia de cálculos renales en pediatría, y los adolescentes representan el grupo etario de más rápido crecimiento a lo largo del espectro de edades afectadas por esta enfermedad.1 Dado que los niños y los adultos jóvenes enfrentan desafíos únicos en términos de prestación de atención, riesgos del tratamiento y procesos patológicos subyacentes, los avances en la enfermedad por cálculos renales en cuanto a la miniaturización del equipamiento, la reducción de la exposición a radiación ionizante y la mejora de la atención de pacientes con predisposición genética a la litiasis urinaria pueden beneficiar de manera preferente a los pacientes pediátricos. Este capítulo revisará los avances no solo en el equipamiento quirúrgico, sino también en el diagnóstico, la terapéutica y la prestación de atención.

Diagnóstico y evaluación inicial

Si bien el ultrasonido (US) sigue siendo la estrategia de imagen de primera línea preferida para la mayoría de los niños con sospecha de nefrolitiasis, esta modalidad de imagen presenta limitaciones en cuanto a la dependencia del operador, la disponibilidad y la precisión.2,3 Por su parte, la tomografía computarizada (CT) es la modalidad de imagen estándar de oro para la precisión diagnóstica, pero conlleva altos riesgos de exposición a radiación ionizante, riesgos que se agravan aún más en la población pediátrica.4 Las innovaciones en el ámbito del diagnóstico por imagen incluyen mejorar la precisión del US, reducir la exposición a radiación asociada a la CT y mejorar funcionalidades adicionales, como la propulsión de cálculos.

Exactitud del ultrasonido

La ecografía se basa en las propiedades sonográficas en la interfaz cálculo-orina para producir la imagen clásica de un foco ecogénico en ecografía en modo B. Además, la desviación de las ondas acústicas en los focos ecogénicos puede producir una sombra acústica posterior, mientras que la aplicación de ajustes Doppler puede crear un artefacto de centelleo sobre el cálculo.5 Ambas técnicas pueden mejorar la precisión de las imágenes ecográficas.6 Además, la sombra acústica posterior tiene el potencial de proporcionar una estimación de tamaño más precisa del cálculo urinario.7 Sin embargo, en la actualidad las modalidades de imagen para captar y realzar estos hallazgos no están bien estandarizadas, ni la identificación y el informe de estas medidas están estandarizados de ninguna manera, y se necesitan más evaluaciones para optimizar las tecnologías actuales y la comprensión de los hallazgos ecográficos. Más allá de la optimización de las tecnologías de imagen actuales, las modificaciones en las propiedades acústicas del equipo de ultrasonido pueden producir características de imagen más distintivas de los cálculos urinarios. Un ejemplo de ello, actualmente utilizado en una plataforma de investigación, es la imagen por ultrasonido Stone-Mode (es decir, “S-mode™”). La imagen S-mode™ se basa en un transductor de alta frecuencia para optimizar la interfaz visual entre el cálculo y el tejido circundante y realzar la apariencia de la sombra acústica. Se minimiza el uso de algoritmos de posprocesamiento que tienden a difuminar las imágenes entre el cálculo denso y la sombra posterior, lo que da como resultado una imagen más nítida del cálculo a costa de una disminución en la imagen de tejidos blandos.8

Tomografías computarizadas de baja dosis

Aunque mejorar las imágenes por ultrasonido es atractivo para minimizar la radiación ionizante en niños con nefrolitiasis, la TC probablemente seguirá siendo una modalidad de imagen clave en el diagnóstico de la nefrolitiasis durante los próximos años. Varios aspectos de los algoritmos actuales de TC con protocolo para cálculos, como la corriente del tubo, el voltaje del tubo y el tiempo del pórtico, pueden reducirse para disminuir la dosis de radiación ionizante durante estos estudios.9 Si bien la TC de baja dosis difícilmente podría clasificarse como una “tecnología del futuro”, dada la gran cantidad de literatura que actualmente respalda su uso, claramente el futuro del manejo de los cálculos podría mejorar al aumentar la adopción de esta tecnología.10 En este sentido, el enfoque para la TC de baja dosis debería centrarse en estrategias para mejorar la formación de los profesionales y el apoyo a la toma de decisiones incorporado en la historia clínica electrónica. Estrategias similares se han utilizado para producir prácticas sostenibles de gestión responsable de la radiación dentro de los departamentos de urgencias pediátricas.11

Propulsión por imágenes

El uso de la propulsión ultrasónica en la enfermedad por cálculos renales se informó por primera vez en ensayos en humanos en 2016.12,13 Esta tecnología, que aprovecha energía acústica focalizada mediante una sonda transcutánea, es capaz de propulsar un cálculo renal dentro del sistema colector renal (Figura 1). Las aplicaciones de esta tecnología incluyen reposicionar cálculos renales obstructivos alejándolos de la unión ureteropélvica, reposicionar los cálculos a una localización de tratamiento más favorable (p. ej., del polo inferior al superior), distinguir entre un pequeño conglomerado de cálculos y un cálculo grande dominante, y favorecer la expulsión de fragmentos más pequeños tras el tratamiento. Los ensayos de factibilidad en humanos observaron movimiento de cálculos en 14 de 15 individuos, incluido uno que refirió alivio inmediato tras el reposicionamiento de un cálculo parcialmente obstructivo.12 El uso intraoperatorio de esta tecnología confirmó visualmente el movimiento de los cálculos durante la ureteroscopia, corroborando un enfoque de prueba de concepto para reposicionar cálculos y facilitar su tratamiento endoscópico.14 Aunque, al momento de redactar este texto, esta tecnología no se ha aplicado en pacientes pediátricos, la ausencia de radiación ionizante y las oportunidades de mejorar tanto los enfoques diagnósticos como terapéuticos la convierten en una tecnología futura atractiva en el ámbito de la nefrolitiasis pediátrica.

Figura 1 Imagen ureteroscópica en tiempo real de la propulsión in vivo de un cálculo calicial de 7 mm mediante propulsión extracorpórea. Figura cortesía de Michael Bailey y Barbrina Dunmire de la Universidad de Washington.

Evaluación metabólica y genética

Mientras que ha habido pocos avances en las evaluaciones tradicionales para la evaluación del riesgo de cálculos renales y de la patología subyacente (p. ej., estudios séricos o urinarios), los avances en la secuenciación genética han ampliado las oportunidades para las pruebas genéticas en el ámbito de la enfermedad litiásica renal de inicio temprano. Las pruebas genéticas no son necesarias para el diagnóstico de ciertas enfermedades monogénicas de cálculos renales con cálculos patognomónicos (p. ej., cistinuria o adenina fosforribosiltransferasa).15 Sin embargo, se ha demostrado que las pruebas genéticas detectan posibles fuentes monogénicas de enfermedad por cálculos renales en hasta el 20% de los niños remitidos a un centro terciario de litiasis renal.16 Entre los aspectos prácticos relacionados con la estrategia diagnóstica de las pruebas genéticas se incluyen la información accionable que puede utilizarse en función de los resultados y la interpretación de variantes de significado incierto. Con respecto al primer aspecto, muchos genes incluidos en los paneles multigénicos más utilizados (a menudo > 30) se manifiestan de manera multisistémica, de modo que el diagnóstico puede sospecharse, si no conocerse, antes de realizar las pruebas genéticas. Además, en la mayoría de estas enfermedades monogénicas de cálculos renales no existe un tratamiento específico y este se guía principalmente por el contexto clínico. No obstante, enfermedades como la hiperoxaluria primaria, en las que la detección precoz puede ser determinante, pueden justificar la realización de pruebas en escenarios con un alto índice de sospecha, como en pacientes más jóvenes o aquellos con un sólido antecedente familiar de nefrolitiasis.17 Cabe destacar que aproximadamente un tercio de las mutaciones descritas son novedosas, lo que plantea interrogantes tanto sobre las implicaciones patológicas de estas variantes de significado incierto como sobre el potencial de ampliar el conocimiento de la litiasis renal de base genética. En tales casos, los análisis bioinformáticos, incluidos modelos de software para predecir la estructura proteica y la posible patogenicidad, pueden orientar la interpretación de resultados inciertos.18 En resumen, las evaluaciones genéticas pueden ser útiles, especialmente al evaluar en busca de fuentes potencialmente tratables de enfermedad litiásica monogénica en poblaciones de alto riesgo, y la colaboración con genetistas puede resultar inestimable para el manejo de variantes de significado incierto o para el asesoramiento.

Prevención

Tecnologías de recordatorios

Independientemente del desarrollo de terapias novedosas para la prevención secundaria de cálculos renales, las medidas dietéticas y de ingesta de líquidos siguen siendo los pilares de las estrategias preventivas.19 No obstante, tanto los clínicos como los pacientes reconocen dificultades para adherirse a estas recomendaciones, especialmente en cuanto a mantener altos volúmenes de ingesta diaria de líquidos. Se han propuesto varias tecnologías novedosas, como botellas de agua “inteligentes” con capacidad para enviar alertas electrónicas justo a tiempo a las familias, como herramientas para mejorar la ingesta de líquidos. De forma notable, aun así, solo el 20% de los adolescentes a quienes se proporcionó esta tecnología alcanzaron sus objetivos de ingesta de líquidos durante la mayor parte de un período de estudio de una semana.20 Otros autores han probado aplicaciones de teléfonos inteligentes y/o tecnología ponible para mejorar la experiencia de ingesta de líquidos, con resultados dispares.21,22 Una vía prometedora para mejorar las tecnologías de recordatorio es el uso de asesoramiento conductual, que actualmente se está explorando en el ensayo Prevention of Urinary Stones with Hydration (PUSH). Al momento de redactar este texto, el ensayo PUSH había finalizado la inclusión de participantes, pero los resultados estaban pendientes.23 Es notable que el estudio cuenta con un brazo de adolescentes, lo que posibilita investigar específicamente la experiencia pediátrica. Si bien el verdadero valor e impacto de las tecnologías de recordatorio para mejorar la adherencia a la prevención secundaria de los cálculos renales sigue siendo esquivo, debe considerarse que el uso de estas tecnologías aún puede evolucionar en cuanto a formato o interfaz, mientras que los cambios generacionales en la adopción tecnológica pueden ampliar aún más las oportunidades para aprovechar tales innovaciones.

Prevención médica

Los avances más destacados en la prevención médica de la enfermedad por cálculos renales incluyen nuevos tratamientos en forma de terapias dirigidas, así como vías innovadoras de impacto farmacéutico. La reciente aprobación por parte de la Asociación de Alimentos y Medicamentos de lumasiran para la Hiperoxaluria primaria tipo 1 marca un avance histórico al ser tanto la primera terapia dirigida para esta enfermedad como el primer fármaco de ARNi aprobado para su uso en enfermedad nefrourológica.24 El medicamento se dirige al ARN mensajero que codifica la oxidasa de glicolato, inhibiendo así la conversión de glicolato a oxalato. Se administra por vía subcutánea cada 1–3 meses y ha sido aprobado para todo el espectro de la población pediátrica, con una dosificación basada en el peso indicada para los niños más pequeños, con aquellos pacientes que pesan menos de 10 kilogramos recibiendo inyecciones mensuales tras una secuencia de carga y aquellos que pesan más de 10 kilogramos recibiendo inyecciones cada tres meses. Los efectos secundarios comunes incluyen reacciones en el sitio de inyección (20%) y dolor abdominal (15%), aunque pocos participantes en los ensayos se retiraron debido a efectos secundarios.

Manejo quirúrgico

Entre la multitud de avances recientes en el manejo quirúrgico de la litiasis urinaria, varios son particularmente relevantes para los pacientes pediátricos. El menor tamaño corporal, incluido el propio uréter, y la susceptibilidad a la exposición a la radiación son solo algunos de los aspectos de la litiasis pediátrica que difieren del tratamiento en pacientes adultos. Las nuevas tecnologías láser han buscado disminuir la retropulsión de los cálculos y aumentar la tasa de ablación, lo que potencialmente conduce a tiempos operatorios más cortos en la ureteroscopia pediátrica (URS). La instrumentación miniaturizada para la nefrolitotomía percutánea (PCNL) puede traducirse en menor morbilidad y sangrado en los pacientes pediátricos. Además, la litotricia por ondas en ráfaga es una tecnología nueva que ofrece tratamiento de la litiasis urinaria en el consultorio, evitando a los niños la anestesia y una recuperación más difícil.

Avances en la tecnología láser

Ha habido varios avances recientes en la tecnología láser, entre ellos optimizaciones del sistema de holmio:YAG, pilar de la litotricia con láser, así como un nuevo láser de fibra de tulio (TFL) que muestra resultados iniciales prometedores. Los avances más recientes en la tecnología del láser de holmio ofrecen menor desplazamiento de los cálculos objetivo durante la fragmentación con láser y la capacidad de aplicar mayor energía, mientras que el TFL ofrece beneficios similares y, además, puede permitir el uso de fibras láser de menor calibre.

Modificaciones del Holmio:YAG

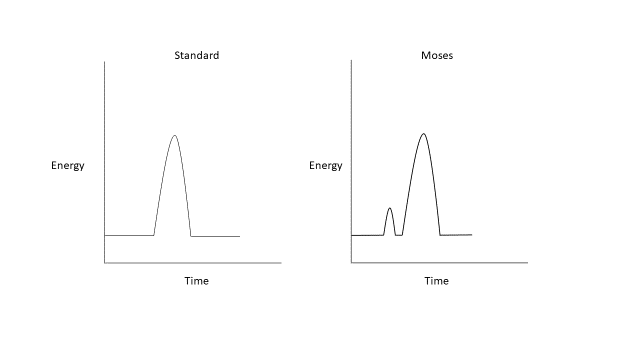

El sistema de holmio:YAG ha sido el patrón de oro para la litotricia con láser desde su introducción, debido a su facilidad de uso y perfil de seguridad favorable.25 Las modificaciones más recientes de esta tecnología, Moses y los modos de pulso largo, alteran este enfoque de pulso único y de duración fija. Los modos de pulso largo entregan la misma cantidad de energía durante un periodo de tiempo más prolongado, típicamente de 500–1000 µs, reduciendo la retropulsión a expensas de una menor entrega de energía.26,27,28,29 El efecto Moses describe un fenómeno físico que ocurre cuando se dispara un láser de holmio en un medio fluido (Figura 2). Esta energía emitida es altamente absorbida por el agua, lo que conduce a la formación de un túnel de vapor. En un pulso único estándar de un láser de holmio, esta transferencia de energía no logra alcanzar la interfaz con el cálculo. La tecnología Moses permite que la energía se entregue en dos pulsos; el primer pulso entrega una pequeña cantidad de energía que provoca la formación de un canal de vapor, mientras que el segundo pulso entrega la mayor parte de la energía, que ahora puede viajar a través del canal de vapor formado hasta el cálculo objetivo.26 Se ha demostrado que la tecnología Moses disminuye el tiempo operatorio en el ámbito clínico debido a la menor retropulsión y a una mayor eficiencia en la fragmentación del cálculo.30,31

Figura 2 Formas de onda del láser de holmio:YAG estándar y Moses.

Fibra de tulio

El TFL genera un haz láser de manera más eficiente que el holmio:YAG, basándose en un láser de diodo que emite luz dentro del pico de absorción de los iones de tulio, excitando así los iones de tulio dentro de una fibra delgada de silicio con una pérdida mínima de energía en forma de calor, lo que permite rangos de frecuencia más altos y rangos más amplios de energía de pulso.25,32 Los parámetros de ejemplo utilizados en la fragmentación de un cálculo renal, así como el generador TFL, pueden verse en Figura 3. Fibras láser más pequeñas, tan pequeñas como 150 µm y 50 µm en desarrollo in vitro, permiten mejorar el flujo de irrigación y la posibilidad de miniaturizar aún más los ureteroscopios.33 El TFL emite luz a una longitud de onda de 1940 nm, aún más cercana al pico de absorción del agua de 1910 nm que la luz emitida por los láseres de holmio:YAG. Esto conduce a un perfil de seguridad favorable, ya que se reduce la profundidad de penetración.34

Figura 3 Configuraciones de ejemplo del TFL, utilizadas para el tratamiento de un cálculo renal (ejemplo mostrado aquí durante una litotricia en adultos).

Múltiples estudios in vitro sugieren que el TFL puede producir tasas de ablación más rápidas y, potencialmente, un mejor aclaramiento de cálculos que el sistema de holmio:YAG.35,36 Sin embargo, existe cierto debate sobre si estas diferencias son clínicamente significativas. Jaeger et al compararon TFL con holmio:YAG durante URS en 125 pacientes pediátricos, 32 de los cuales fueron tratados con TFL. Los pacientes tratados con TFL presentaron menor probabilidad de tener fragmento de cálculo residual, sin diferencias significativas en el tiempo operatorio ni en la tasa de complicaciones, si bien con un tiempo de láser más prolongado en el grupo TFL.37 Un metanálisis de estudios clínicos en adultos que incluyó cerca de 1.700 pacientes mostró varias ventajas con TFL en comparación con holmio:YAG, incluyendo mejores tiempos operatorios y de utilización del láser, menor retropulsión y mayor aclaramiento de cálculos. No hubo diferencias en la eficiencia de ablación, el consumo total de energía ni la estancia hospitalaria.38

Debido tanto a que la energía emitida es muy similar al pico de absorción del agua como a la capacidad de operar a potencias y frecuencias más altas, el calor y la lesión térmica son motivo de mayor preocupación con el TFL que con un láser de holmio. Además, modelos simulados han demostrado que los pacientes más jóvenes con riñones más pequeños pueden ser más susceptibles a la lesión térmica durante la ureteroscopia para cálculos renales. Sin embargo, estos efectos pueden mitigarse con el uso de una vaina de acceso y una irrigación continua presurizada39

Miniaturización de PCNL

Las primeras experiencias con la PCNL en pacientes pediátricos se complicaron por tasas más altas de sangrado y una mayor proporción de pacientes que necesitaron transfusiones de sangre después de sus procedimientos debido al uso de instrumentos más grandes, de tamaño para adultos (hasta 30 Fr).40,41 Ha habido avances significativos en la miniaturización de los instrumentos necesarios para realizar la PCNL; esto ha llevado a un mayor uso de la PCNL en la población pediátrica con tasas de complicaciones más bajas.42 La mini-PCNL fue descrita por primera vez en 1998 por Jackman et al en un intento por desarrollar una técnica de PCNL menos invasiva que disminuyera la morbilidad en niños pequeños.42 Cabe destacar que esta innovación inicialmente descrita en niños también se ha afianzado entre la población adulta.

Ulteriores esfuerzos por miniaturizar la PCNL han dado lugar a la PCNL ultramini (UMP) (11–13 Fr) y a la micro-PCNL (4.8 Fr). La UMP puede realizarse con un nefroscopio o un ureteroscopio utilizando fragmentación con láser y ha mostrado una eliminación de cálculos equivalente a la mini-PCNL, aunque con tiempos operatorios más prolongados.43,44 La micro-PCNL representa el trayecto de acceso más pequeño reportado actualmente para procedimientos de PCNL miniaturizados, utilizando una “aguja de visión total” que mide 4.85 Fr y tiene una luz que puede alojar una fibra láser de 200 micras.45 Es importante señalar que esta técnica no permite la extracción significativa de fragmentos de cálculo directamente a través del trayecto de acceso.

Existen múltiples ventajas de reducir el tamaño de la instrumentación en la PCNL incluyendo: menor sangrado, menor traumatismo del parénquima renal y menor dolor relacionado con el trayecto de acceso. Una revisión sistemática reciente buscó evaluar la eficacia y las complicaciones de las técnicas de PCNL mínimamente invasivas en pacientes pediátricos.46 Se incluyeron un total de 14 estudios que comprendieron 456 pacientes que se sometieron a micro-PCNL o UMP. El tamaño medio de los cálculos osciló entre 12 y 16.5 mm. La tasa libre de cálculos osciló entre 80–100% y se observaron complicaciones en el 14% de los pacientes. El 77% de las complicaciones fueron grado I o II de Clavien-Dindo. Las complicaciones incluyeron hematuria, fiebre, fuga de orina, ITU, necesidad de transfusión y 3 pacientes con perforación de la pelvis renal. En general, la tasa de transfusión en esta revisión sistemática fue del 2.1%. La PCNL mínimamente invasiva ha demostrado ser segura en pacientes pediátricos. Sin embargo, existen algunas desventajas incluyendo menor claridad visual e incapacidad para extraer los cálculos a través del trayecto de acceso para la micro-PCNL. También ha habido cierta evidencia de un aumento de la presión intrarrenal en la mini-PCNL.47 Con un abanico cada vez mayor de opciones para el manejo quirúrgico de la litiasis renal pediátrica, la UMP y la micro-PCNL representan una opción atractiva que debe considerarse en pacientes con una carga litiásica renal moderada.

Avances en la fragmentación ultrasónica de cálculos: litotricia por ondas de ráfaga

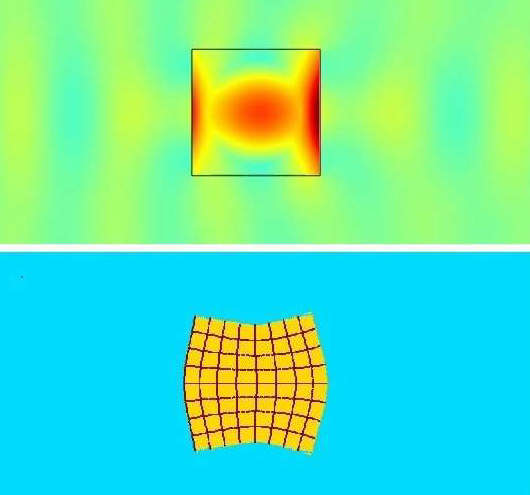

Aunque históricamente la SWL se ha utilizado como terapia de primera línea para fragmentar cálculos en la población pediátrica, el procedimiento requiere anestesia general y, con avances más recientes en las técnicas endoscópicas, ha caído en desuso en muchas situaciones: particularmente en pacientes con mayor carga litiásica, composiciones litiásicas más duras, mayor distancia piel-cálculo y enfermedad litiásica en el polo inferior del riñón.48 La SWL consiste en aplicar un ciclo único de energía a una frecuencia lenta (0.5–3 Hz) para fragmentar los cálculos. La litotricia por ondas en ráfaga (BWL) es una modalidad relativamente nueva en exploración que utiliza ráfagas sinusoidales de varios ciclos de pulsos de ultrasonido focalizado para fracturar los cálculos, en lugar del único ciclo de compresión/tensión generado por la SWL (Figura 4). La BWL ofrece una terapia potencial que podría utilizarse en un entorno de consultorio o sala de sedación sin necesidad de anestesia general, lo cual sería una opción atractiva para muchos pacientes pediátricos.13

Figura 4 Simulación de litotricia por ondas de ráfaga (BWL) a través de la interfaz del cálculo. La imagen superior muestra las ondas de presión amarillas y azul verdoso desplazándose a través del cálculo, con una amplificación central del esfuerzo de 5 veces dentro del cálculo debido a los múltiples ciclos de pulso de la BWL. La imagen inferior muestra una representación exagerada de la distorsión del cálculo inducida por el esfuerzo, debida a la amplificación del esfuerzo descrita previamente. Imagen cortesía de Oleg Sapozhnikov de la Universidad de Washington.

Existen varias diferencias importantes en las propiedades generadas por la BWL en comparación con la SWL tradicional. En la SWL, un pulso de aproximadamente 5 µs se repite cada 0.33 a 2 segundos, lo que da como resultado 180 ondas de choque por minuto. La BWL se administra usando 10–100 ciclos a la vez y se ha investigado en un rango de 300–500 kHz en humanos.13 La amplitud máxima de una forma de onda de SWL es aproximadamente 10 veces mayor que en la BWL. Sin embargo, la BWL puede entregar la misma cantidad de energía debido al uso de muchos más ciclos que el único pulso de energía de la SWL. Además, mientras que la SWL crea una nube de cavitación en un área focal que puede causar lesión tisular, en la BWL hay un crecimiento más suave de las burbujas de cavitación. Las nubes de burbujas son más difusas y no suelen sufrir un colapso violento, lo que potencialmente minimiza el daño celular.49 Aunque hay cierta evidencia de que las nubes de burbujas más difusas generadas en la BWL pueden llevar al apantallamiento del cálculo objetivo frente a pulsos posteriores, la BWL puede superar esta limitación escalando la entrega de energía.50 Un modelo mostró que usar frecuencias específicas para distintos tamaños de cálculos puede amplificar la tensión interna en un cálculo generada por la BWL, una opción no disponible en la SWL estándar.51

Existen datos limitados sobre el uso de BWL en el entorno clínico, y debe señalarse que este tratamiento aún no se ha estudiado en niños.52 Las experiencias clínicas actuales se resumen en Tabla 1. El ensayo más grande reportado hasta la fecha, de 19 pacientes, trató cálculos < 12 mm durante hasta 10 minutos con BWL. Una mediana del 90% del volumen del cálculo presentó conminución completa en 10 minutos y el 39% de los cálculos objetivo se fragmentaron con todas las piezas <2 mm en 10 minutos.53 Otro estudio trató a 13 pacientes despiertos y sin anestesia tanto con propulsión ultrasónica como con BWL, con un 70% de eliminación de cálculos reportada y una puntuación media de dolor de 1,2/10 durante el tratamiento.54

Tabla 1 Resumen de la búsqueda en PubMed de evaluaciones de litotricia por ondas de ráfaga en ensayos en humanos.

| Año | Autor | Título | Resultados clave | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | Harper | Primera litotricia por ondas de ráfaga en humanos para la conminución de cálculos renales: dos estudios de caso iniciales54 | El paciente A tuvo una BWL exitosa para un cálculo renal observado mediante URS. El paciente B recibió BWL con el paciente despierto para un cálculo de 7.5 mm en la UVJ, toleró bien el procedimiento y el cálculo se expulsó en el día postoperatorio 15. | |

| 2022 | Harper | Fragmentación de cálculos mediante litotricia por ondas de ráfaga en los primeros 19 humanos10 | 21 de 23 cálculos se fragmentaron. Conminución mediana de los cálculos del 90%. Fragmentación completa en <10 minutos para 9/23 cálculos. | |

| 2022 | Hall | Primera serie que utiliza propulsión ultrasónica y litotricia por ondas de ráfaga para tratar cálculos ureterales11 | 13 pacientes tratados con BWL en conjunto con propulsión ultrasónica. El 70% de los pacientes que se sometieron a BWL con el paciente despierto expulsaron el cálculo. Puntuación media de dolor durante la BWL 1.2/10. |

Conclusiones

En muchos aspectos—como las estrategias de imagen optimizadas, los inhibidores de ARN para la hiperoxaluria primaria y los avances quirúrgicos en tecnología láser y PCNL miniaturizada—el futuro del manejo de los cálculos renales pediátricos ya está aquí. Sin embargo, estas tecnologías deben comprenderse mejor en términos de su uso clínico más eficaz, cuestiones que están maduras para la investigación de efectividad comparativa. Otros avances tecnológicos, como la propulsión por imagen y la BWL, permanecen en el horizonte del manejo, aunque ofrecen vías prometedoras hacia tratamientos en niños en las próximas varias décadas.

Referencias

- Tasian GE, Ross ME, Song L, Sas DJ, Keren R, Denburg MR, et al.. Annual Incidence of Nephrolithiasis among Children and Adults in South Carolina from 1997 to 2012. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016; 11 (3): 488–496. DOI: 10.2215/cjn.07610715.

- Roberson NP, Dillman JR, O’Hara SM, DeFoor WR, Reddy PP, Giordano RM, et al.. Comparison of ultrasound versus computed tomography for the detection of kidney stones in the pediatric population: a clinical effectiveness study. Pediatr Radiol 2018; 48 (7): 962–972. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-018-4099-7.

- Ellison JS, Thakrar P. The Role of Imaging in Management of Stone Disease. Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric. Nephrolithiasis: Springer; 2022. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-031-07594-0\\_8.

- Frush DP. Pediatric CT: practical approach to diminish the radiation dose. Pediatr Radiol 2002; 32 (10): 714–717. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-002-0797-1.

- Dai JC, Bailey MR, Sorensen MD, Harper JD. Innovations in Ultrasound Technology in the Management of Kidney Stones. Urol Clin North Am 2019; 46 (2): 273–285. DOI: 10.1016/j.ucl.2018.12.009.

- Masch WR, Cohan RH, Ellis JH, Dillman JR, Rubin JM, Davenport MS. Clinical Effectiveness of Prospectively Reported Sonographic Twinkling Artifact for the Diagnosis of Renal Calculus in Patients Without Known Urolithiasis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2016; 206 (2): 326–331. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.15.14998.

- Verhagen MV, Watson TA, Hickson M, Smeulders N, Humphries PD. Acoustic shadowing in pediatric kidney stone ultrasound: a retrospective study with non-enhanced computed tomography as reference standard. Pediatr Radiol 2019; 49 (6): 777–783. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-019-04372-x.

- Simon JC, Dunmire B, Bailey MR, Sorensen MD. Developing Complete Ultrasonic Management of Kidney Stones for Spaceflight. J Space Saf Eng 2016; 3 (2): 50–57. DOI: 10.1016/s2468-8967(16)30018-0.

- Lira D, Padole A, Kalra MK, Singh S. Tube Potential and CT Radiation Dose Optimization. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204 (1): W4–w10. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.14.13281.

- Niemann T, Kollmann T, Bongartz G. Diagnostic Performance of Low-Dose CT for the Detection of Urolithiasis: A Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 191 (2): 396–401. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.07.3414.

- Ellison JS, Crowell CS, Clifton H, Whitlock K, Haaland W, Chen T, et al.. A clinical pathway to minimize computed tomography for suspected nephrolithiasis in children. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (5): 518.e1–518.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.06.014.

- Harper JD, Cunitz BW, Dunmire B. Faculty Opinions recommendation of First in human clinical trial of ultrasonic propulsion of kidney stones. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2016; 195: 956, DOI: 10.3410/f.725901820.793511249.

- Raskolnikov D, Bailey MR, Harper JD. Recent Advances in the Science of Burst Wave Lithotripsy and Ultrasonic Propulsion. BME Front 2022; 2022. DOI: 10.34133/2022/9847952.

- Dai JC, Sorensen MD, Chang HC, Samson PC, Dunmire B, Cunitz BW, et al.. Quantitative Assessment of Effectiveness of Ultrasonic Propulsion of Kidney Stones. J Endourol 2019; 33 (10): 850–857. DOI: 10.1089/end.2019.0340.

- Goldstein R, Goldfarb DS. Early Recognition and Management of Rare Kidney Stone Disorders. Urol Nurs 2017; 37 (2): 81. DOI: 10.7257/1053-816x.2017.37.2.81.

- Daga A, Majmundar AJ, Braun DA, Gee HY, Lawson JA, Shril S, et al.. Whole exome sequencing frequently detects a monogenic cause in early onset nephrolithiasis and nephrocalcinosis. Kidney Int 2018; 93 (1): 204–213. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.06.025.

- Langman CB. A rational approach to the use of sophisticated genetic analyses of pediatric stone disease. Kidney Int 2018; 93 (1): 15–18. DOI: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.08.023.

- Ma Y, Lv H, Wang J, Tan J. Heterozygous mutation of SLC34A1 in patients with hypophosphatemic kidney stones and osteoporosis: a case report. J Int Med Res 2020; 48 (3): 030006051989614. DOI: 10.1177/0300060519896146.

- Tasian GE, Copelovitch L. Evaluation and Medical Management of Kidney Stones in Children. J Urol 2014; 192 (5): 1329–1336. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.108.

- Tasian GE, Ross M, Song L. Ecological Momentary Assessment of Factors Associated with Water Intake Among Adolescents with Kidney Stone Disease. 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2018.07.064.

- Conroy DE, West AB, Brunke-Reese D, Thomaz E, Streeper NM. Just-in-time adaptive intervention to promote fluid consumption in patients with kidney stones. Health Psychol 2020; 39 (12): 1062–1069. DOI: 10.1037/hea0001032.

- Wright HC, Alshara L, DiGennaro H, Kassis YE, Li J, Monga M, et al.. The impact of smart technology on adherence rates and fluid management in the prevention of kidney stones. Urolithiasis 2022; 50 (1): 29–36. DOI: 10.1007/s00240-021-01270-6.

- Scales CD, Desai AC, Harper JD, Lai HH, Maalouf NM, Reese PP, et al.. Prevention of Urinary Stones With Hydration (PUSH): Design and Rationale of a Clinical Trial. Am J Kidney Dis 2020; 77 (6): 898–906.e1. DOI: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2020.09.016.

- Garrelfs SF, Frishberg Y, Hulton SA. Lumasiran, an RNAi Therapeutic for Primary Hyperoxaluria Type 1. N Engl J Med 2021; 385 (20): e69. DOI: 10.1056/nejmc2107661.

- Traxer O, Keller EX. Thulium fiber laser: the new player for kidney stone treatment? A comparison with Holmium:YAG laser. World J Urol 2020; 38 (8): 1883–1894. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-019-02654-5.

- Aldoukhi AH, Black KM, Ghani KR. Emerging Laser Techniques for the Management of Stones. Urol Clin North Am 2019; 46 (2): 193–205. DOI: 10.1016/j.ucl.2018.12.005.

- Kang HW, Lee H, Teichman JMH, Oh J, Kim J, Welch AJ. Dependence of calculus retropulsion on pulse duration during HO: YAG laser lithotripsy. Lasers Surg Med 2006; 38 (8): 762–772. DOI: 10.1002/lsm.20376.

- Bell JR, Penniston KL, Nakada SY. In Vitro Comparison of Holmium Lasers: Evidence for Shorter Fragmentation Time and Decreased Retropulsion Using a Modern Variable-pulse Laser. Urology 2017; 107: 37–42. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.06.018.

- Kronenberg P, Traxer O. Update on lasers in urology 2014: current assessment on holmium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet (Ho:YAG) laser lithotripter settings and laser fibers. World J Urol 2015; 33 (4): 463–469. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-014-1395-1.

- Wang M, Shao Q, Zhu X, Wang Z, Zheng A. Efficiency and Clinical Outcomes of Moses Technology with Flexible Ureteroscopic Laser Lithotripsy for Treatment of Renal Calculus. Urol Int 2021; 105 (7-8): 587–593. DOI: 10.1159/000512054.

- Ibrahim A, Fahmy N, Carrier S, Elhilali M, Andonian S. Double-blinded prospective randomized clinical trial comparing regular and moses modes of holmium laser lithotripsy: Preliminary results. European Urology Supplements 2020; 17 (2): e1390. DOI: 10.1016/s1569-9056(18)31815-3.

- Panthier F, Doizi S, Berthe L, Traxer O. In vitro comparison of ablation rates between superpulsed thulium fiber laser and ho:Yag laser for endocorporeal lithotripsy. Eur Urol Open Sci 2020; 19: e1884–e1885. DOI: 10.1016/s2666-1683(20)33870-2.

- Khusid JA, Khargi R, Seiden B, Sadiq AS, Atallah WM, Gupta M. Thulium fiber laser utilization in urological surgery: A narrative review. Investig Clin Urol 2021; 62 (2): 136. DOI: 10.4111/icu.20200467.

- Taratkin M, Azilgareeva C, Cacciamani GE, Enikeev D. Thulium fiber laser in urology: physics made simple. Curr Opin Urol 2022; 32 (2): 166–172. DOI: 10.1097/mou.0000000000000967.

- Andreeva V, Vinarov A, Yaroslavsky I, Kovalenko A, Vybornov A, Rapoport L, et al.. Preclinical comparison of superpulse thulium fiber laser and a holmium:YAG laser for lithotripsy. World J Urol 2020; 38 (2): 497–503. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-019-02785-9.

- Jiang P, Okhunov Z, Afyouni AS, Ali SN, Sharifi H, Bhatt R, et al.. Comparison of Superpulse Thulium Fiber Laser vs. Holmium Laser for Ablation of Renal Calculi in an In-Vivo Porcine Model. J Endourol 2022. DOI: 10.1089/end.2022.0445.

- Jaeger CD, Nelson CP, Cilento BG, Logvinenko T, Kurtz MP. Comparing Pediatric Ureteroscopy Outcomes with SuperPulsed Thulium Fiber Laser and Low-Power Holmium:YAG Laser. J Urol 2022; 208 (2): 426–433. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000002666.

- Chua ME, Bobrowski A, Ahmad I. Thulium fibre laser vs holmium: yttrium-aluminium-garnet laser lithotripsy for urolithiasis: meta-analysis of clinical studies. 2022. DOI: 10.1111/bju.15921.

- Ellison JS, MacConaghy B, Hall TL, Roberts WW, Maxwell AD. A simulated model for fluid and tissue heating during pediatric laser lithotripsy. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (5): 626.e1–626.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.07.014.

- Quhal F, Al Faddagh A, Silay MS, Straub M, Seitz C. Paediatric stone management: innovations and standards. Curr Opin Urol 2022; 32 (4): 420–424. DOI: 10.1097/mou.0000000000001004.

- Zeren S, Satar N, Bayazit Y, Bayazit AK, Payasli K, Özkeçeli R. Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in the Management of Pediatric Renal Calculi. J Endourol 2002; 16 (2): 75–78. DOI: 10.1089/089277902753619546.

- Jackman SV, Hedican SP, Peters CA, Docimo SG. Percutaneous nephrolithotomy in infants and preschool age children: experience with a new technique. Urology 1998; 52 (4): 697–701. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00315-x.

- Wright A, Rukin N, Smith D, Rosette J De la, Somani BK. ‘Mini, ultra, micro’ – nomenclature and cost of these new minimally invasive percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL) techniques. Ther Adv Urol 2016; 8 (2): 142–146. DOI: 10.1177/1756287215617674.

- Mishra DK, Bhatt S, Palaniappan S, Reddy TVK, Rajenthiran V, Sreeranga YL, et al.. Mini versus ultra-mini percutaneous nephrolithotomy in a paediatric population. Asian J Urol 2022; 9 (1): 75–80. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajur.2021.06.002.

- Desai MR, Sharma R, Mishra S, Sabnis RB, Stief C, Bader M. Single-Step Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy (Microperc): The Initial Clinical Report. J Urol 2011; 186 (1): 140–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.03.029.

- Jones P, Bennett G, Aboumarzouk OM, Griffin S, Somani BK. Role of Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Techniques–Micro and Ultra-Mini PCNL (<15F) in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. J Endourol 2017; 31 (9): 816–824. DOI: 10.1089/end.2017.0136.

- Loftus CJ, Hinck B, Makovey I, Sivalingam S, Monga M. Mini Versus Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: The Impact of Sheath Size on Intrarenal Pelvic Pressure and Infectious Complications in a Porcine Model. J Endourol 2018; 32 (4): 350–353. DOI: 10.1089/end.2017.0602.

- Silay MS, Ellison JS, Tailly T, Caione P. Update on Urinary Stones in Children: Current and Future Concepts in Surgical Treatment and Shockwave Lithotripsy. Eur Urol Focus 2017; 3 (2-3): 164–171. DOI: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.07.005.

- Maeda K, Colonius T. Bubble cloud dynamics in an ultrasound field. J Fluid Mech 2019; 862: 1105–1134. DOI: 10.1017/jfm.2018.968.

- Maeda K, Maxwell AD, Colonius T. Investigation of the Energy Shielding of Kidney Stones by Cavitation Bubble Clouds during Burst Wave Lithotripsy. Proceedings of the 10th International Symposium on Cavitation (CAV2018) 2018; 144: 626–630. DOI: 10.1115/1.861851_ch119.

- Sapozhnikov OA, Maxwell AD, Bailey MR. Maximizing mechanical stress in small urinary stones during burst wave lithotripsy. J Acoust Soc Am 2021; 150 (6): 4203–4212. DOI: 10.1121/10.0008902.

- Harper JD, Metzler I, Hall MK. Faculty Opinions recommendation of First In-Human Burst Wave Lithotripsy for Kidney Stone Comminution: Initial Two Case Studies. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2020. DOI: 10.3410/f.738685997.793585856.

- Harper JD, Lingeman JE, Sweet RM. Re: Fragmentation of Stones by Burst Wave Lithotripsy in the First 19 Humans. Eur Urol 2022; 82 (5): 569. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2022.07.012.

- Hall MK, Thiel J, Dunmire B. First Series Using Ultrasonic Propulsion and Burst Wave Lithotripsy to Treat Ureteral Stones. Letter. J Urol 2022; 209 (2): 325–326. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000003060.

Última actualización: 2025-09-25 12:10