39: Seno urogenital

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 13 minutos para leer.

Introducción

El seno urogenital aislado es una anomalía congénita poco frecuente del sistema urogenital femenino en la que la uretra y la vagina no llegan a separarse durante el desarrollo, formando un canal común. Las anomalías del seno urogenital se encuentran en cuatro escenarios clínicos diferentes:1

- Estados de ambigüedad genital (como la hiperplasia suprarrenal congénita)

- Cloaca persistente con afectación rectal

- Extrofia vesical femenina

- Seno urogenital aislado

Este capítulo se centrará en el seno urogenital aislado.

Epidemiología

La incidencia del seno urogenital aislado no se conoce bien, aunque las fuentes informan una tasa de incidencia que oscila entre 6/100,000 y 1/250,000 nacimientos de sexo femenino.2,3

Embriología/Etiología

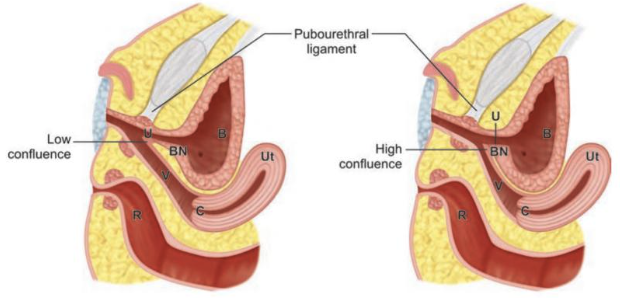

El seno urogenital común (SUG) es una estructura transitoria normal del desarrollo embrionario que posteriormente se separa y da origen a la uretra y al tercio distal de la vagina. La etiología del seno urogenital aislado no se comprende bien, pero en general se acepta que es el resultado de una detención del desarrollo de la formación urogenital femenina en el primer trimestre, en la cual la uretra y la vagina no logran formar orificios perineales separados.4 Se postula que una detención temprana de la diferenciación vaginal dará lugar a un canal común largo (confluencia alta), mientras que una detención más tardía de la diferenciación formará un canal común corto (confluencia baja) (Figura 1).5

Figura 1 Diagrama que muestra confluencia baja (izquierda) y confluencia alta (derecha). Observe la ubicación de la confluencia de la uretra (U) y la vagina (V) en relación con el cuello vesical (BN) y el ligamento pubouretral. Otras estructuras representadas incluyen el útero (Ut), la vejiga (B), el recto (R) y el cuello uterino (C). Carrasco “Técnicas quirúrgicas en urología pediátrica y del adolescente”.6

Evaluación clínica

Presentación clínica

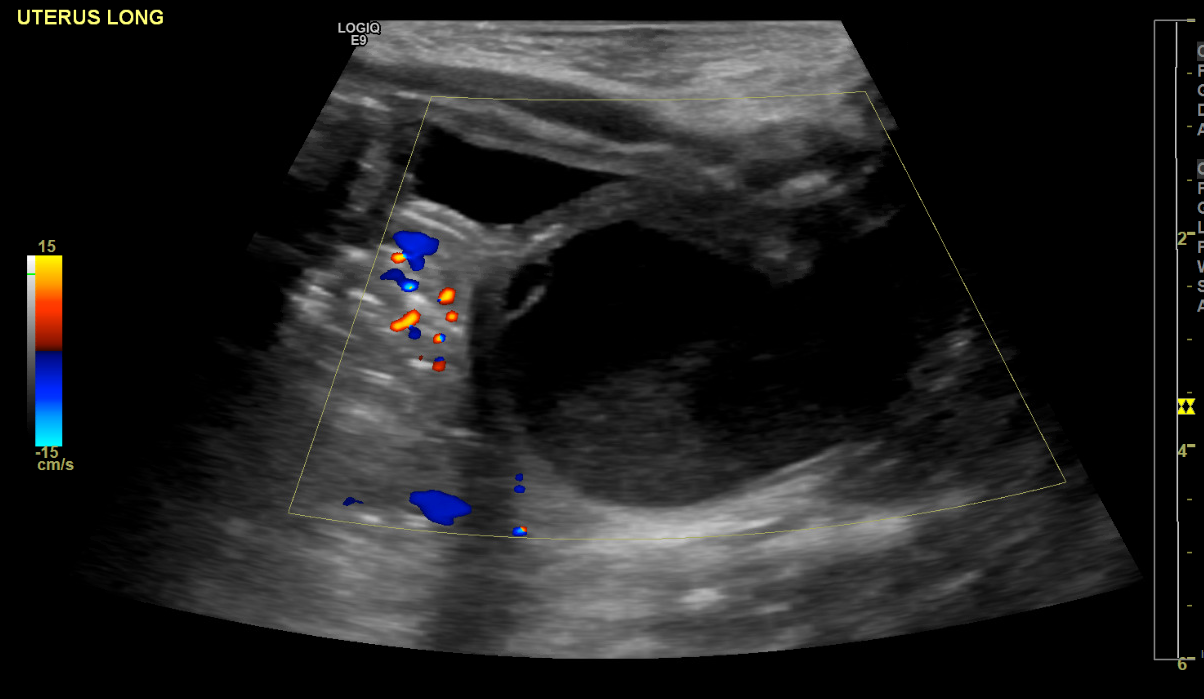

Muchos casos se identifican mediante ultrasonografía prenatal que muestra estructuras pélvicas llenas de líquido que a menudo representan hidrocolpos o hidrometrocolpos (Figura 2).1,6

Figura 2 Ecografía que muestra la vejiga anteriormente y un hidrocolpos posteriormente.

Signos y síntomas de presentación: los pacientes que no fueron identificados en la ecografía prenatal pueden presentarse posteriormente con lo siguiente:

- Infección del tracto urinario

- Incontinencia urinaria

- Goteo posmiccional

- Acumulación de líquido en la vagina

- Hematuria menstrual7

- O puede ser asintomático

Examen físico

La exploración física debe incluir:

- Exploración abdominal

- Puede revelar una masa suprapúbica palpable que representa una vejiga distendida y/o hidrometrocolpos1

- Exploración de la columna

- Debe completarse la exploración de la columna lumbosacra, ya que las anomalías del seno urogenital pueden asociarse con anomalías de la médula espinal1

- Exploración genital

- Mostrará un único orificio perineal (Figura 3)

- Para examinar a los lactantes, el uso de aplicadores con punta de algodón puede ayudar a separar los labios para visualizar adecuadamente el orificio perineal.

Figura 3 Orificio perineal único en el examen genital. Imagen adaptada de Grey’s Anatomy, lámina 1119 (imagen de dominio público).

Pruebas diagnósticas

Estudios de imagen

El papel de las técnicas de imagen en la evaluación diagnóstica del seno urogenital aislado es limitado. Debe realizarse una ecografía del sistema urinario y del sistema reproductor para descartar cualquier otra anomalía y definir la localización de esos órganos.1

Se puede obtener un genitograma para delimitar mejor la anatomía, pero puede tener una utilidad limitada en el seno urogenital aislado.

Puede ser necesaria la obtención de imágenes de la columna vertebral para evaluar anomalías de la médula espinal.

Endoscopia

La herramienta diagnóstica más importante en el seno urogenital aislado son la cistoscopia y la vaginoscopia. Esto permite al cirujano evaluar la longitud del canal común y la ubicación de la confluencia uretral y vaginal en relación con el cuello vesical, lo cual es crucial para determinar el abordaje quirúrgico apropiado.6 Esta evaluación endoscópica se realiza en el momento de la reparación quirúrgica y se abordará con más detalle en una sección posterior de este capítulo.

Manejo quirúrgico

Manejo inmediato

Si un paciente requiere drenaje de hidrocolpos, se pueden colocar bajo anestesia un catéter a través del canal común (intermitente o de permanencia), un catéter suprapúbico o realizar una vaginostomía. De lo contrario, es probable que la orina continúe acumulándose en la vagina y/o el útero. Puede ser necesaria la cateterización hasta una reparación reconstructiva posterior.

Manejo definitivo

Indicaciones quirúrgicas

La reparación quirúrgica está indicada si los pacientes presentan síntomas relacionados con el seno urogenital, especialmente si existen problemas de acumulación de orina, como hidronefrosis o hidrocolpos.6 Si los pacientes están asintomáticos, la reparación quirúrgica puede diferirse.

Asesoramiento preoperatorio

Objetivos quirúrgicos

Los objetivos de la reparación quirúrgica deben discutirse con los padres antes de proceder y deben incluir lo siguiente:

- genitales de aspecto normal

- orificios separados para la uretra y la vagina

- drenaje de la orina

- orificio vaginal de tamaño adecuado para productos menstruales y futuras relaciones sexuales

Momento de la cirugía

Recomendamos que la reparación quirúrgica se realice entre los 6 y los 12 meses de edad.6 El momento óptimo para el seno urogenital aislado no se ha establecido en la literatura y se extrapola a partir de pacientes con hiperplasia suprarrenal congénita y seno urogenital asociado.

Quienes favorecen la reparación quirúrgica temprana sostienen que los tejidos pueden ser más maleables a una edad temprana y que el estrógeno materno residual circulante puede promover la cicatrización de las heridas.1 Quienes favorecen la reparación quirúrgica a la edad de la pubertad promueven los mismos beneficios hormonales, además de la participación del paciente y su asentimiento para proceder.1

Técnicas quirúrgicas

Preparación preoperatoria

- No es necesaria la preparación intestinal

- Deben administrarse antibióticos preoperatorios para cubrir la flora cutánea y vaginal

- La reparación quirúrgica comprende 2 partes distintas:

- Evaluación endoscópica para determinar la longitud del canal y su relación con el cuello vesical

- Reparación definitiva mediante vaginoplastia

- El abordaje de la vaginoplastia se determina por la evaluación endoscópica

Examen bajo anestesia y cistoscopia y vaginoscopia

El/la paciente debe colocarse en posición de litotomía dorsal. La exploración bajo anestesia (EUA) debe incluir la evaluación del introito y del orificio perineal único.

A continuación, debe completarse la evaluación endoscópica. Durante esta evaluación, el cirujano debe medir la longitud de ciertos parámetros anatómicos, como la longitud de la uretra, la vagina y el canal común en relación con el cuello vesical. La longitud del canal y su relación con el cuello vesical son los parámetros más cruciales para determinar el abordaje quirúrgico de la reparación definitiva.

- Longitud del canal de < 3 cm → vaginoplastia con colgajo o PUM/TUM

- Longitud del canal de > 3 cm → vaginoplastia pull-through o abordaje sagital anterior transrectal (ASTRA)

La evaluación endoscópica debe comenzar con una cistoscopia utilizando un cistoscopio rígido del tamaño adecuado. El cistoscopio debe avanzarse a través del canal común, hacia la uretra, que será el orificio anterior, y luego hacia la vejiga. La vejiga debe inspeccionarse minuciosamente para asegurarse de que no existan otras anomalías anatómicas.

A continuación se realiza la vaginoscopia con el cistoscopio. Se deben evaluar el tamaño general, la elasticidad y la forma (es decir, anomalías de duplicación).6

Una vez completadas la exploración bajo anestesia y la evaluación endoscópica, el cirujano debe determinar cuál es el abordaje de vaginoplastia más adecuado para la paciente.

Movilización urogenital total y parcial

Descrito por primera vez por: Alberto Pena en 19979

Indicaciones: Longitud uretral adecuada, no se anticipa una disección extensa a nivel del cuello vesical

Posición: variable, dependiendo del método de vaginoplastia

Descripción breve: Se diseca todo el seno de manera circunferencial y se moviliza hacia el periné.1

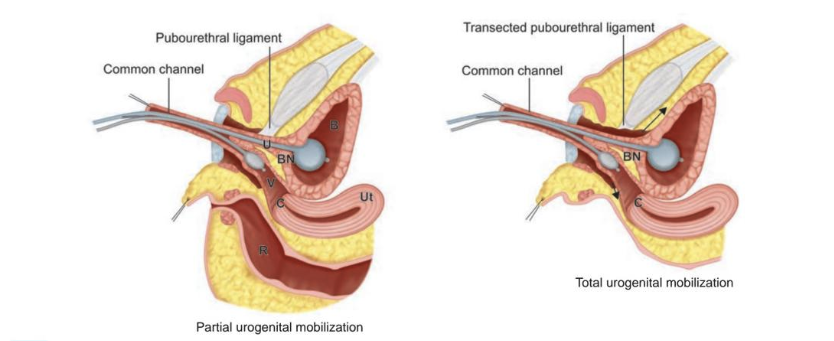

Esto se clasifica como movilización urogenital parcial (PUM) o movilización urogenital total (TUM) según si se secciona el ligamento pubouretral (Figura 4).6 Este procedimiento también permite la movilización de todo el seno para proporcionar un vestíbulo revestido de mucosa. Permite que una confluencia de nivel medio alcance el perineo sin requerir separación vaginal.

Pasos

- El UGS se marca circunferencialmente en su unión con los labios menores y a lo largo de la línea media del periné hacia el borde anterior del ano

- La disección comienza en la pared posterior del UGS, extendiendo lateralmente y luego anteriormente hasta que el UGS quede movilizado circunferencialmente

- La disección de la pared lateral y anterior debe mantenerse medial al músculo bulboesponjoso para evitar sangrado

- La movilización debe continuar hasta que la uretra y la vagina puedan alcanzar el introito con mínima o nula tensión6

- La movilización urogenital parcial se detiene al nivel del ligamento pubouretral para reducir el posible riesgo de incontinencia de esfuerzo o acortamiento de la vagina (Figura 4)

Figura 4 Movilización urogenital parcial (izquierda) y total (derecha) con catéteres en la vejiga (B) y la vagina (V) para facilitar la tracción. Nótese que en la movilización urogenital total, se secciona el ligamento pubouretral y la disección se continúa en sentido proximal (flechas) hasta que la uretra y la vagina puedan alcanzar el periné. Otras estructuras representadas incluyen el útero (Ut), el cuello vesical (BN) y el recto (R). Fuente: Carrasco “Surgical Techniques in Pediatric and Adolescent Urology”.6

Vaginoplastia con colgajo

Descrito por primera vez por: Fortunoff et al en 196410

Indicaciones: confluencia baja, canal común corto

Posición: litotomía

Descripción breve: El introito y el seno urogenital se abren ampliamente; el nivel de confluencia no cambia

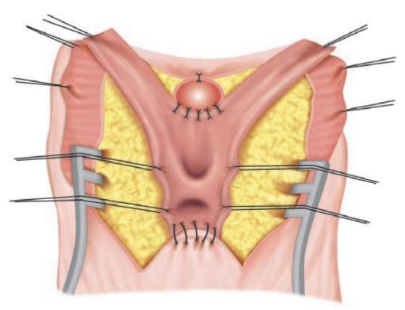

Durante este procedimiento, se abren las paredes posteriores del seno y de la vagina, se deja intacta la pared anterior de la vagina, y el colgajo perineal posterior se coloca dentro de la vagina abierta; por lo tanto, la piel cubre el aspecto posterior del introito y de la pared vaginal.

Pasos

- Se realiza una incisión en U invertida o en forma de omega sobre el periné en el borde posterior del UGS.11

- El colgajo debe ser lo suficientemente largo para permitir una anastomosis a la vagina sin tensión y lo suficientemente ancho para proporcionar un introito de calibre normal sin comprometer la irrigación del cuerpo perineal.1

- Se diseca el UGS en paralelo a la pared posterior del UGS hacia la pared vaginal posterior, alejándose del recto

- Debe minimizarse la disección lateral para evitar el sangrado

- La disección posterior debe continuar hasta que la confluencia pueda alcanzar fácilmente el introito

- Una vez completada la disección posterior, se divide la pared posterior del UGS en la línea media, así como la pared vaginal posterior, hasta lograr una abertura vaginal de tamaño adecuado

- Luego, el punto medio del colgajo cutáneo perineal se sutura a la pared vaginal posterior dividida (Figura 5)

Figura 5 Diagrama que muestra la vaginoplastia con colgajo. Se ha incidido el canal común en la línea media, exponiendo la uretra y la vagina. Obsérvese el anclaje del ápex anterior del UGS y el anclaje del ápex posterior al colgajo cutáneo en U. La pared redundante del canal común puede resecarse o utilizarse para reconstrucción adicional de la horquilla. Fuente: Carrasco “Surgical Techniques in Pediatric and Adolescent Urology”.6

Vaginoplastia de descenso

Descrito por primera vez por: Hendren y Crawford en 196913

Indicaciones: confluencia alta con longitud uretral corta, o si se anticipa una movilización extensa del cuello vesical6

Posición: prono

Descripción breve: La vagina se separa del seno urogenital y se lleva por separado al periné, mientras que el UGS se utiliza para crear una uretra. Esto es ideal cuando existe gran longitud vaginal con excelente elasticidad.6

Pasos

- Se crea un colgajo cutáneo perineal posterior similar al de la vaginoplastia con colgajo

- Se disecan las paredes posteriores y laterales del UGS, extendiéndose hasta las paredes posteriores y laterales de la vagina

- El cuerpo perineal se puede dividir para obtener exposición adicional si es necesario

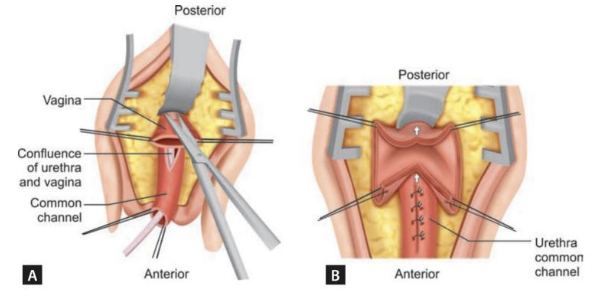

- Se incide luego la pared vaginal posterior en su unión con el UGS para exponer la confluencia de la uretra y la vagina

- Se separa la pared uretral posterior de la pared vaginal anterior (Figura 6, A)

- Con frecuencia no hay un verdadero plano entre estas estructuras

- La disección debe inclinarse hacia el lado vaginal para minimizar el riesgo de lesión de la uretra (incluido el esfínter1), el cuello vesical y los uréteres

- La disección se realiza lo más proximal posible hasta que el orificio vaginal pueda llevarse al periné con mínima tensión

- Se cierra el defecto del canal común y ahora el canal común pasa a ser la uretra (Figura 6, B)

- El colgajo perineal posterior se sutura a la vagina de manera similar a la vaginoplastia con colgajo

Figura 6 Diagrama que muestra la vaginoplastia de descenso. A: Se ha incidido la pared vaginal posterior a nivel de la confluencia de la uretra y la vagina. B: Las paredes vaginales anterior y posterior se disecan proximalmente (flechas) para permitir la movilización de la vagina hacia el periné. Nótese que la unión de la vagina al canal común está cerrada, haciendo del canal común una continuación de la uretra. Fuente: Carrasco “Surgical Techniques in Pediatric and Adolescent Urology”.6

Abordaje sagital transrectal anterior

Descrito por primera vez por: Domini et al en 199714

Indicaciones: confluencia alta

Posición: prono

Descripción breve: Se accede a la confluencia alta por vía posterior a través de la pared rectal anterior para separar la vagina del seno urogenital

Pasos

- Se realiza una incisión perineal en la línea media desde el borde anal anterior hasta el orificio del UGS.15

- Se inciden la pared rectal anterior y el esfínter anorrectal, exponiendo la pared vaginal posterior

- Se incide la pared vaginal posterior lo más cerca posible de la unión con la uretra

- La vagina se moviliza posterolateralmente y luego se diseca de la uretra

- Se cierra el orificio uretral

- La vagina se lleva al periné, utilizando colgajos de piel perineal si es necesario

- La pared anorrectal se cierra en 2 capas

- Se reconstruyen el esfínter anorrectal y el cuerpo perineal

Enfoques laparoscópicos y asistidos por robot

Hay pocos informes sobre enfoques laparoscópicos y robóticos para la reparación del seno urogenital.16,17 El enfoque laparoscópico o robótico permite la disección del útero y la vagina, separándolos de la vejiga y el recto desde el interior del abdomen. Posteriormente, la vagina se moviliza hasta el periné.

Cuidados postoperatorios

- El cuidado posoperatorio es variable, según la magnitud de la reparación quirúrgica y la edad del paciente.6

- Un paciente joven sometido a una reparación más mínima (p. ej., vaginoplastia con colgajo) podría ser dado de alta a casa el mismo día.

- Un paciente de mayor edad sometido a una reparación más extensa (p. ej., vaginoplastia tipo pull-through) debe ser ingresado para observación.

- Puede considerarse el taponamiento vaginal en pacientes adolescentes.

- La duración del catéter Foley es de 3–7 días para una vaginoplastia con colgajo, y al menos 7 días para todas las demás reparaciones.

- Se debe aplicar una pomada a base de vaselina en el introito al menos 4 veces al día durante las primeras semanas para crear una barrera entre las líneas de sutura y evitar la adherencia de la ropa interior a la herida y de los tejidos entre sí.

Complicaciones postoperatorias

Complicaciones inmediatas

- Sangrado: puede minimizarse con taponamiento vaginal en pacientes pospuberales.6

- Necrosis del colgajo: rara

- Favorecer la reparación diferida para prevenir la fibrosis tisular local

- Infección de la herida: rara

- Generalmente se maneja con antibióticos

- Dehiscencia de la herida: poco común si la anastomosis estaba libre de tensión

- Puede manejarse de forma conservadora para permitir la cicatrización por segunda intención

- Retención urinaria: rara

- Si el paciente no puede orinar, se debe reemplazar el catéter por un catéter Coudé. Esto es particularmente importante después de una vaginoplastia pull-through, ya que la pared posterior del UGS es delicada y propensa a la formación de falsa vía.6

- Formación de fístula: mayor riesgo tras una vaginoplastia pull-through

- Puede ocurrir en cualquier parte del tracto urinario inferior, pero la localización más común es en la confluencia del canal común donde se separó la vagina

Complicaciones tardías y resultados quirúrgicos

Los datos sobre los resultados a largo plazo tras la reparación aislada del seno urogenital son muy limitados. La mayoría de los datos sobre los resultados de la vaginoplastia provienen de pacientes con hiperplasia suprarrenal congénita, quienes tienden a presentar una anatomía más compleja y requieren otros procedimientos adyuvantes.6

- Vaginoplastia con colgajo:

- No hay informes de incontinencia, lo cual concuerda con la disección mínima requerida

- Puede presentar micción vaginal debido a un meato hipospádico

- Crecimiento de vello intravaginal a partir del colgajo de piel perineal, lo que puede interferir con las relaciones sexuales

- Estenosis vaginal:

- La tasa varía ampliamente de 3% a 83%

- La tasa de revisión quirúrgica también abarca un amplio rango de 25% a 86%

- Por lo general puede manejarse con dilatación vaginal

- Los datos de resultados de PUM, TUM y vaginoplastia pull-through son limitados

- Puede tener mayor riesgo de incontinencia dado el grado de disección del suelo pélvico requerido.6

- Parece tener menor riesgo de estenosis vaginal

- Resultados de ASTRA:

Puntos clave

- El seno urogenital aislado es una anomalía congénita rara del sistema urogenital femenino en el que la uretra y la vagina no se separan durante el desarrollo, formando un conducto común.

- El diagnóstico se realiza principalmente mediante examen físico de los genitales externos de una paciente que muestra un único orificio perineal.

- La cistoscopia y el examen bajo anestesia se realizan habitualmente para comprender mejor la anatomía. La genitografía es opcional.

- Las técnicas de reconstrucción quirúrgica dependen de la longitud del conducto común. Los conductos más largos requieren técnicas quirúrgicas más invasivas para movilizar la uretra y la vagina hasta la piel. Los conductos más cortos son más frecuentes y tienen resultados excelentes tras la reconstrucción.

Conclusión

El seno urogenital es una malformación congénita poco frecuente que da lugar a que la uretra y la vagina confluyan en un canal común que se presenta como un único orificio perineal. Esto se observa comúnmente en pacientes con hiperplasia suprarrenal congénita. La evaluación y la reconstrucción pueden variar, pero en general, para canales comunes cortos, los resultados suelen ser favorables a corto y mediano plazo. Debe realizarse seguimiento de las pacientes durante la pubertad para evaluar la vagina y determinar su adecuación antes de la menarquia.

Lecturas recomendadas

- Carrasco A. Urogenital Sinus Reconstruction. Surgical Techniques in Pediatric and Adolescent Urology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2020.

Referencias

- Rink RC. Surgical Management of Differences of Sexual Differentiation and Cloacal and Anorectal Malformations. In: Partin AW, Dmochowski RR, Kavoussi LR, Peters CA, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021.

- Clavelli A. Persistent Urogenital Sinus. J Anat Soc India 2004; 59 (2): 1. DOI: 10.1016/s0003-2778(10)80034-6.

- Urogenital Sinus. The Fetal Medicine Foundation; . DOI: 10.1515/iupac.88.1463.

- Rowe CK, Merguerian PA. Developmental Abnormalities of the Genitourinary System. Avery’s Diseases of the Newborn 2023: 1260–1273. DOI: 10.1016/b978-0-323-82823-9.00076-3.

- Grosfeld JL, Coran AG. Abnormalities of the Female Genital Tract. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2006; 2: 1935–1955. DOI: 10.1016/b978-0-323-02842-4.50125-x.

- Carrasco A. Urogenital Sinus Reconstruction. Surgical Techniques in Pediatric and Adolescent Urology. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2020.

- Ding Y, Wang Y, Lyu Y, Xie H, Huang Y, Wu M, et al.. Urogenital sinus malformation: From development to management. Intractable Rare Dis Res 2023; 12 (2): 78–87. DOI: 10.5582/irdr.2023.01027.

- Tan HH, Tan SK, Shunmugan R, Zakaria R, Zahari Z. A Case of Persistent Urogenital Sinus: Pitfalls and challenges in diagnosis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2018; 17 (4): 455. DOI: 10.18295/squmj.2017.17.04.013.

- Eapen A, Chandramohan A, Simon B, Putta T, John R, Kekre A. Imaging Evaluation of Disorders of Sex Development. Journal of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology 2020; 03 (02): 181–192. DOI: 10.1055/s-0039-3402101.

- Vaginoplasty technique for female pseudohermaphrodites. Plast Reconstr Surg 1964; 34 (3): 322. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-196409000-00031.

- Jenak R, Ludwikowski B, González R. Total Urogenital Sinus Mobilization: A Modified Perineal Approach For Feminizing Genitoplasty And Urogenital Sinus Repair. J Urol 2001; 165 (6 Part 2): 2347–2349. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200106001-00032.

- Yang J, Syed H, Baker Z, Vasquez E. Urogenital Sinus Diagnosed During Workup of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections: A Case Report. Urology 2023; 174: 165–167. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2022.12.031.

- Fares AE, Marei MM, Abdullateef KS, Kaddah S, El Tagy G. Laparoscopically Assisted Vaginal Pull-Through in 7 Cases of Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia with High Urogenital Sinus Confluence: Early Results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2019; 29 (2): 256–260. DOI: 10.1089/lap.2018.0194.

- Rink RC, Cain MP. Urogenital mobilization for urogenital sinus repair. BJU Int 2008; 102 (9): 1182–1197. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.08091.x.

- Hardy Hendren W, Crawford JD. Adrenogenital syndrome: The anatomy of the anomaly and its repair. Some new concepts. J Pediatr Surg 1969; 4 (1): 49–58. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3468(69)90183-3.

- Dòmini R, Rossi F, Ceccarelli PL, Castro RD. Anterior sagittal transanorectal approach to the urogenital sinus in adrenogenital syndrome: Preliminary report. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32 (5): 714–716. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90012-9.

- Salle JLP, Lorenzo AJ, Jesus LE, Leslie B, AlSaid A, Macedo FN, et al.. Surgical treatment of high urogenital sinuses using the anterior sagittal transrectal approach: a useful strategy to optimize exposure and outcomes. J Urol 2012; 187 (3): 1024–1031, DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.10.162.

- Leite MTC, Fachin CG, Albuquerque Maranhão RF de, Shida MEF, Martins JL. Anterior sagittal approach without splitting the rectal wall. Int J Surg Case Rep 2013; 4 (8): 723–726. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.05.013.

- Huen KH, Holzman SA, Davis-Dao CA, Wehbi EJ, Khoury AE. Taking “Trans-ano-rectal” out of ASTRA: An anterior sagittal approach without splitting the rectum. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 18 (1): 96–97. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.12.007.

- Peña A. Total urogenital mobilization–An easier way to repair cloacas. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32 (2): 263–268. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90191-3.

Última actualización: 2025-09-25 12:10