23: Updates in Exstrophy Management

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 19 minutos para leer.

Introduction

The exstrophy-epispadias complex (EEC) comprises a wide spectrum of congenital anomalies, all arising from the same embryological defect, ranging from simple glandular epispadias to cloacal exstrophy.1

Epidemiology

The Bladder exstrophy-epispadias-cloacal exstrophy complex (BEEC) is more frequent in caucasians. Classic bladder exstrophy (BEX) is the predominant subtype (50%), occurring in 2.15 - 3.3/100,000 live births, and cloacal exstrophy (CEX) is seen in 1/200,000. In recent decades there has been an increase in diagnostic suspicion with advances in fetal medicine.2,3

There is a male predominance and the male to female ratio has been reported between 2.3-6:1.4 However, cloacal exstrophy is the same in both genders (1:1).

Mortality in patients with bladder exstrophy is low (4%). Thanks to advances in surgical techniques and current management, the long-term survival of these patients is excellent, reporting improvements in fertility and sexual function for both women and men with BEX. Furthermore, the survival of children with CEX has improved from 50% in 1960 to more than 80% today.

Etiopathogenesis

Embryology

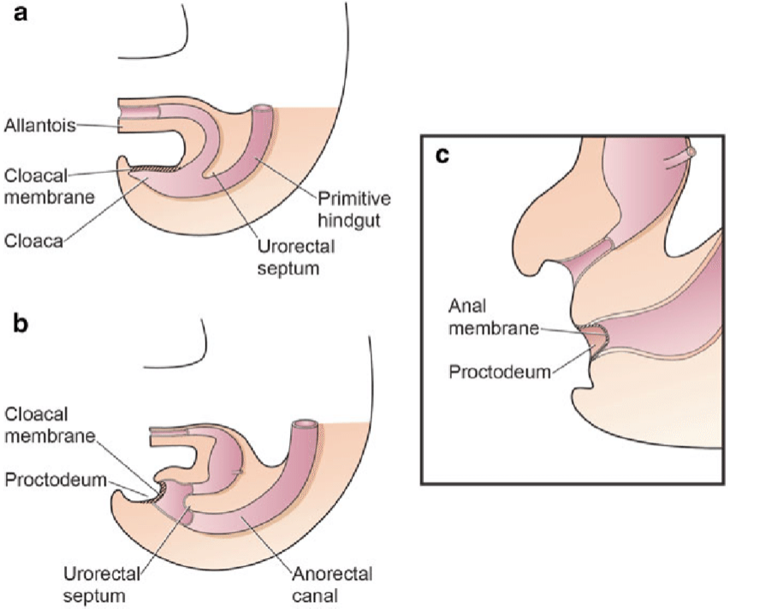

The separation of the primitive cloaca into the urogenital sinus and hindgut occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy, about the same time that the anterior abdominal wall is formed. The cloacal membrane is a bilaminar layer located at the caudal end of the germinal disc that occupies the infraumbilical abdominal wall. Mesodermal ingrowth between the ectodermal and endodermal layers of the bilaminar cloacal membrane results in formation of the lower abdominal musculature and pelvic bones. After mesenchymal ingrowth occurs, the urorectal septum advances caudally and divides the cloaca into the bladder anteriorly and the rectum posteriorly. Distally, the septum meets the posterior remnant of the bilaminar membrane, which eventually perforates and forms the urogenital and anal openings. The paired genital tubercles migrate medially and fuse in the midline, cephalad to the dorsal membrane before perforation. A failure in the migration of mesenchymal cells between the ectodermal and endodermal layers of the lower abdominal wall causes instability of the cloacal membrane.5 The premature rupture of this membrane, prior to its caudal migration, leads to the development of this group of infraumbilical anomalies. The extent of the infraumbilical defect and the stage of development when the rupture occurs determines whether bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, or epispadias results. If the rupture occurs after complete separation of the genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts, classic BEX occurs. However, if this occurs before the descent of the urorectal septum, there is externalization of the lower urinary tract and the distal portion of the gastrointestinal tract, giving rise to cloacal exstrophy (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Division of the cloaca into an anterior primitive urogenital sinus and a posterior rectum between the 4th and 6th weeks of gestation

The most related theory of embryonic development in exstrophy, held by Marshall and Muecke,6 describes the basic defect as an abnormal lower overdevelopment of the cloacal membrane, which prevents the medial migration of the mesenchymal tissue. Therefore, proper development of the abdominal wall does not occur. The timing of the rupture of this cloacal defect determines the severity of the disorder. Central perforations resulting in classic exstrophy have the highest incidence (60%) whereas exstrophy variants account for 30% and cloacal exstrophy 10%.

Other theories are offered concerning the cause of the exstrophy-epispadias complex.7,8 Ambrose and O’Brian9 postulated that an abnormal development of the genital hillocks with fusion in the midline below rather than above the cloacal membrane result in the exstrophy defect. Another hypothesis describes an abnormal caudal insertion of the body stalk with failure of the interposition of the mesenchymal tissue in the midline.10 Because of this failure, translocation of the cloaca into the depths of the abdominal cavity does not occur. A cloacal membrane that remains in a superficial infraumbilical position represents an unstable embryonic state with a strong tendency to disintegrate.11 No one theory seems to elucidate all aspects of the complex seen clinically and further study is ongoing to fully describe the developmental process that ultimately forms the exstrophy-epispadias complex.

Etiology

The exact etiology of this disease has not yet been identified. Nevertheless, it has been confirmed that the triggering event occurs early in pregnancy.8 Multiple ongoing studies suggest a possible genetic basis for the development of these conditions.11 There is a higher incidence in children of mothers who received large doses of progesterone in early stages of pregnancy, as in cases of assisted reproduction therapies, and it is estimated that the incidence is up to 7.5 times higher in cases where in vitro fertilization was used.11

Recurrence Risk

The possible role of genetic factors implicated in the expression of EEC is based on the increased recurrence risk for offspring of affected individuals.8 Among siblings, Ives et al estimated the recurrence risk to be approximately 1% in non-consanguineous and non-affected parents of BEX cases.12 Shapiro et al.13 estimated the risk of recurrence for siblings of European background for isolated BEX as 1 in 275, having surveyed 2,500 CEB families. They also described a 400-fold increased risk of classic BEX in offspring of affected individuals compared to the general population. Based on a prevalence of 3.3:100,000 (~1:30.000) for isolated BEX among populations of European background, the recurrence risk ratio in siblings has been calculated to be 108 (1:275/1:30.000 ~108).14 While female EEC patients represent the minority of patients, interestingly, only affected females produced affected offspring.13 Among other explanations, this superficial higher recurrence risk for affected females may be due to a higher genetic liability for EEC (so-called Carter effect).15

Familial Recurrences

Although familial occurrence is rare, 30 reported multiplex families support the idea of genetic susceptibility underlying EEC.16 In most of these families, two members are affected. However, in rare cases the inheritance of EEC may be consistent with autosomal dominant inheritance with reduced penetrance or with an autosomal recessive trait or X-linked transmission.17 These observations indicate that one or more genes with a major effect on the phenotype exist, though in most cases additional causal factors are necessary for the phenotype to occur. A small subgroup of cases may follow Mendelian inheritance whereas in the majority, EEC is inherited as a complex trait with multiple genetic factors (heritable or *de novo *somatic or germ line mutations), and complex gene-gene, or gene-environment interactions contributing to its formation.8

Molecular Genetics of the EEC

Cytogenetic and molecular analyses have revealed chromosomal anomalies in 20 EEC patients to date, although none of these appear to be causative.8 Numerical chromosomal aberrations were observed in six patients. In a further four BEX males, one BEX female and one girl with CEX, an association with Down syndrome was found.16 Aneuploidy of sex chromosomes in five of these cases might point to a gonosomal locus involved in the formation of EEC. Structural aberrations have been identified in six EEC cases and one patient simultaneously presenting with CEX and hypomelanosis of Ito. Although the exact breakpoints have not been determined in any of these cases, several translocations involving the region q32-ter on chromosome 9 were detected.

Teratogenic Agents and EEC

Twin studies and epidemiological data suggest environmental factors play a role in the EEC etiology. However, the existing epidemiological studies have not identified major teratogenic factors.4,12,18 Several studies have confirmed that male gender, race, advanced parental age4 and increased parity, even after adjusting for age,19 are predisposing risk factors. Gambhir et al.18 described periconceptional maternal exposure to smoking to be significantly more common in patients with CEX than in a combined group of patients with epispadias and classic BEX. Several reports described the occurrence of EEC in infants resulting from *in vitro *fertilization, but it is still a matter of debate whether the incidence of EEC children conceived by *in vitro *fertilization appears to be higher than expected.8,20

Clinical Presentation

Antenatal Period

Despite the magnitude of the defect in the lower abdominal wall and pelvic organ development, exstrophy of the bladder is still difficult to diagnose reliably by prenatal ultrasound.21 This is likely because of its rare incidence and that it is often mistaken for more common diagnoses of omphalocele or gastroschisis.

It is possible to suspect these conditions during pregnancy when:

- The bladder is not identified on successive ultrasounds (absent bladder filling).

- There is a decrease in the thickness of the abdominal wall.

- There is a lower abdominal mass which becomes more prominent as the pregnancy progresses.

- There is a low-set umbilical cord.

- The genitalia have an abnormal position (anterior or posterior) and there are difficulties determining the sex of the baby

- The phallus is short.

- There is an increase in the pelvic diameter, with separation of the pubic rami.

- There is an omphalocele.

- There is evidence of anomalies of the lower extremities and/or myelomeningocele (suggestive of cloacal exstrophy).

Three-dimensional ultrasound and the increasing use of fetal MRI will improve the ability to diagnose bladder and cloacal exstrophy.21 Antenatal diagnosis allows for prenatal counseling and arrangements to be made for delivery at a specialized exstrophy center. This allows for a multidisciplinary approach by teams with experience dealing with the unique nature of the exstrophy-epispadias complex.

Neonatal Period

Most variants are easily identifiable at birth.

- Bladder exstrophy is usually seen more in term infants with good birth weight.

- Newborns with cloacal exstrophy are usually preterm, and small for the gestational age.

Childhood

- Infrequent variants may go unnoticed.

- They are usually identified later in life only by persistent urinary incontinence or gait disturbances.

Physical Exam

In classic BEX, most abnormalities consist of defects of the abdominal wall, bladder, genitalia, pelvic bones, and anus, thus involving the lower urinary tract, genitalia, and musculoskeletal system (limbs), while in cloacal exstrophy there is a greater involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and CNS.

Classic Bladder Exstrophy

The abdominal wall is elongated, and the umbilicus is low-set, located on the upper edge of the bladder plate; it can be associated with a hernial defect or a small omphalocele. The bladder is open anteriorly, with its mucosa fully exposed; polyps may be seen on the surface. Urine drains from the ureteric orifices on the bladder surface. Delayed closure may lead to further inflammatory or mechanical alterations with signs of mucosal inflammation such as a whitish coating, ulcerations, and hyperplastic formations. The para-exstrophic shiny thin skin stripes mark the transition between the normal skin and the squamous metaplastic area. The anus is more anterior, but the sphincteric function is normal. The pubic bones are widely separated and may also be shortened and externally rotated (30%). They are palpable on both sides of the bladder template and the distal end of the triangular edges. Bilateral inguinal hernias are palpable in most patients of both genders.

- Female BEX: there is a bifid clitoris, separated labia majora, and a divergent mons pubis (Figure 2). The vagina is shorter than normal, not more than 6 cm deep, but of normal caliber. The vaginal opening is often stenotic and anteriorly placed. As the anus is ventrally positioned as well, the perineum is shortened.

- Male BEX: The genital defect is severe and is probably one of the most problematic aspects of surgical reconstruction. The urethral plate is open and extends along a short, wide, and dorsally curved phallus, from the open bladder to the glandular grove. Both corpora cavernosa are located beneath the urethral plate. Careful examination reveals the colliculus seminalis and the ductus ejaculatorii as tiny openings in the area, where the prostate is presumably dorsally located. The glans is open and flat (Figure 3), and the normal-sized testes are usually located in the scrotum.

Figure 2 Classic BEX with a low-set umbilicus and an anteriorly placed anus in the perineum. Female BEX with an open bladder and urethral plate, with a split clitoris.

Figure 3 Male BEX with a short, wide, and dorsally curved phallus. Abnormal distance between the scrotum and penis.

Epispadias

The defect results from a developmental arrest in terms of non-closure of the urethral plate and additionally in an abnormal dorsal urethral location. Therefore, in males an ectopic meatus or a mucosal strip is found on the penile dorsum and in females a variable cleft of the urethra is detected.8 Abdominal wall and rectus muscles, as well as the umbilicus, are completely normally developed. The pubic symphysis is usually closed, or only a minor gap is present, indicating only minor pelvic and pelvic floor anomalies. Urinary incontinence appears to be the main clinical symptom, depending on the degree of involvement of the urinary sphincter. In most distal epispadias, involuntary urine loss is not observed, whereas in proximal cases urine is dripping permanently through the meatus. Due to the sometimes “minor” clinical abnormalities, distal epispadias might be missed at birth, especially in girls. Then diagnosis may made later in school age, due to urinary incontinence, resistant to standard treatment.

- **Male epispadias (Figure 4): According to the meatal location, epispadias is distinguished as either penopubic, penile or glandular.

- **Female epispadias (Figure 5): is divided into three degrees according to Davis, either less severe with a gaping meatus, intermediate or severe with a cleft involving the whole urethra and the bladder neck, additionally displaying bladder mucosal prolapse.

Figure 4 Male epispadias

Figure 5 Female epispadias

Cloacal Exstrophy

The rectus muscles and the pubic bones are separated. The bladder is open on the lower abdominal wall and divided into 2 halves adjacent to the exposed segment of the cecum. The openings that communicate the terminal ileum, the appendix (one or two), and the distal intestine are evident within the cecal plate, and the terminal ileum may prolapse as a "trunk" through it (elephant trunk appearance). It presents with an imperforate anus and may be associated with an omphalocele. 95% have myelodysplasia and 65% have a malformation of the lower extremities.

-

Male CEX: the phallus is usually bifid and small, with each hemiglans located caudal to each hemibladder, or it may be absent.

-

Female CEX: the clitoris is bifid and there may be two hemivaginas with a bicornuate uterus (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Cloacal exstrophy. Giant omphalocoele with 2 hemibladders adjacent to the extrophic caecal plate. Small and bifid phallus, with its hemiglans and a hemiscrotum placed distal to the each bladder plate.

Exstrophy Variants

This includes a clinically wide and heterogeneous spectrum of anomalies. The covered exstrophy appears similar to the classic BEX, with part of the bladder mucosa covered with skin; it may also present as a severe epispadias with a prolapsed bladder. The umbilicus might be at an orthotopic place. Pseudo-exstrophy, however, may be very difficult to identify after birth and is often found at older ages. The genitalia appear normal, and the patients may not have any urinary symptoms, some being completely continent. On physical examination, rectus diastasis of various degrees may be found. The pelvic X-rays could demonstrate an open pubic symphysis, although it is not uncommon for it to be an incidental finding.

Associated Anomalies

Urological Anomalies

Several urological malformations are present in about one third of all EEC cases, predominantly in the EC population (ureteropelvic junction obstruction, ectopic pelvic kidney, horseshoe kidney, renal agenesis, megaureter, ureteral ectopy and ureterocele).1,8 All patients should undergo an antireflux procedure with every bladder neck plasty, as there is a 100% prevalence of bilateral vesicoureteral reflux due to a developmental failure of the ureterovesical junction throughout the EEC spectrum.

Spinal and Orthopaedic Anomalies

he incidence of spinal anomalies varies within the EEC spectrum. In children born with CEB, spinal anomalies occur in about 7% of cases, whereas a heterogeneous group of congenital spinal anomalies resulting from defective closure of the neural tube early in fetal life and anomalous development of the caudal cell mass can be confirmed with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified in nearly 100% of CEX patients.8 A neurological component must be kept in mind in these patients in regards to their bladder and lower extremity function, and erectile capacity.22,23 Skeletal and limb anomalies (clubfoot deformities, absence of feet, tibial or fibular deformities, and hip dislocations) are more commonly seen in CEX.1,8 However, there are no reports about hip dysplasia in long-term follow-up of the EEC.

Gastrointestinal Anomalies

These are predominantly associated with CEX. In addition to a common hindgut remnant of varying size, omphalocoeles are found in 88-100% of CEX cases. Gastrointestinal malrotation or duplication, as well as short bowel syndrome, can be seen in up to 46% of cases.1,8 In about 25% of cases, an either anatomical or functional short bowel syndrome causes absorptive dysfunction.

Gynaecological Anomalies

In addition to the abnormal external genitalia, the cervix inserts low down at the superior vaginal wall close to the introitus in most cases.1,8,24 Nevertheless, the anatomy and function of the uterus and the adnexae are normal. The pelvic floor and the levator defect, together with the absence of the cardinal ligaments, predisposes women to vaginal or uterine prolapse in about 50% of cases. Müllerian anomalies are quite common in CEX, i.e., duplication of the vagina and uterus, vaginal agenesia.1,8

Imaging Studies

They are usually performed to identify and diagnose possible associated anomalies (pelvic and abdominal malformations, spine and vertebral cord anomalies, etc).

The main studies are renal ultrasound, spinal cord ultrasound, and x-rays of the spine and pelvis. All newborns with CEX should have spinal ultrasound and radiographs to define the individual spinal abnormalities ranging from hemivertebra to myelomeningocele. MRI is further recommended in follow-up to identify occult spinal abnormalities predisposing to symptomatic spinal cord tethering.

Sonographic evaluation of the hip joints is of fundamental impact for all EEC patients. Plain pelvic X-ray can be helpful to estimate the dimension of the symphysis gap and the hip localization.

Diagnosis

Antenatally, the EEC can be suspected from the 16th week of gestation. With the advances in the sensitivity of antenatal ultrasonography there has been an increase in prenatal suspicion.

In most cases the malformation is diagnosed at birth, as it becomes evident clinically.

Management

If there is an antenatal diagnosis or suspicion of EEC, the ideal is to counsel the parents and the delivery should be scheduled in a specialized center (refer if necessary). There is no experience that supports the indication of fetal surgery. Vaginal delivery is not recommended due to the increased risk of injury to the bladder plate.

Nowadays, it is no longer consider an emergency and/or surgical emergency, allowing for a transfer in safe conditions to specialized centres that can take care of these children with low-frequency and highly complex malformations.

The surgical approach initially focused on urinary diversion to preserve renal function. However, since the first successful bladder closure was reported by Young in 1942,1,8,11,24,25 significant advances have been made in the areas of staged reconstruction, in the appearance of the external genitalia, and in the preservation of continence and renal function. With improvements in surgical technique, as well as perioperative care, excellent long-term survival can now be expected.

Surgery

The objectives of the current surgical approach are;1 reconstruction of the abdominal wall,2 relocation and anatomic closure of the exstrophic bladder,3 preserving renal function and achieving urinary continence, and4 reconstruction of the external genitalia.26,27,28,29,30 Historically, the reconstruction was performed in 3 stages beginning in the neonatal period. However, there are currently super-specialized centres or multicentric teams that manage the condition and can organize deferred management, in order to offer the best to each patient by accumulating experience in low-frequency and highly complex pathologies.31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40

The Surgical Stages are

- Closure of the bladder, with approximation of the pubic bones, without the need for osteotomies. In patients with CEX, intestinal diversion should be performed.

- The second stage consists of complete genital reconstruction. In some centres, the Kelly Procedure or a Radical Soft Tissue Reconstruction is also performed, to achieve bladder continence and a greater penile length in men.

- Finally, urinary continence should be assessed in the medium to long term. For those cases in which this objective has not been achieved yet or when there is a risk of renal function compromise, there is a third stage in which bladder neck surgery and/or augmentation cystoplasty can be performed with a continent urinary diversion for clean intermittent catheterization.

In various super-specialized centres around the world, delayed closure at two to four months of age has been chosen, performing a single-stage approach, together with the surgery described by Kelly,26,30,39 which includes:1 dissection and bladder closure with or without an antireflux procedure (if bladder size and wall characteristics allow it);2 the radical soft tissue mobilization with disinsertion from the pubic rami;3 the creation of a bladder neck or continence mechanism with the help of the Peña stimulator to identify the neo-muscular sphincter complex and4 penile reconstruction or introitoplasty.

The benefits of this approach are that prior surgery in the neonatal period is avoided, allowing for the presence of the native tissues, and avoiding scarring and fibrosis generated by primary closure. This also favors parental attachment and the development of a bond between the child and their parents, without the need for a prolonged hospitalization within the first days of life.

It has been demonstrated that delayed bladder closure can be performed safely and successfully, and that in principle it does not affect bladder development. Delaying surgery allows for maturation of the newborn, with the consequent reduction in the risks of a prolonged anesthesia and favors the growth of the infant during the period of mini-puberty, in addition to promoting the preparation of the team of experts for each case.39

Complications

Because of its complexity and very low frequency, these conditions present a series of complications mostly associated with the reconstructive surgery:34,39

- Early: surgical wound dehiscence, bladder prolapse, urethral or vesicocutaneous fistulae (4 – 19%), urethral stenosis (8%), penile ischemia.

- Late: VUR, recurrent UTIs, incomplete bladder emptying, urinary incontinence, bladder lithiasis, abdominal wall fibrosis, bladder rupture, uterine prolapse, renal failure, retrograde ejaculation, oligospermia and infertility, and short gut syndrome and fecal incontinence (cloacal exstrophy).

Prognosis

If these patients are left untreated, they would suffer from recurrent urinary tract infections, permanent urinary incontinence and problems with sexual activity, also having a higher risk of bladder cancer, which together means a poorer quality of life.26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35

However, if proper management of the condition is accomplished as suggested, these patients have a quality of life expectancy that is probably similar to that of the general population. It is also estimated that they will potentially be able to live an absolutely normal life, considering that in more than 90% of cases there is no association with other congenital malformations. In addition, these patients could develop urinary continence without requiring a bladder augmentation or intermittent catheterization for emptying, even though the success rate is reserved (only 23% of voluntary urination per urethra with the MSRE technique,41 39% with the CPRE technique,28 and 53% with the Kelly technique26).

Table 1 Wide range of continence rate of the different approaches depending on definition of continence and observation period.42

| Approach | Continence rate (%) | Literature |

|---|---|---|

| MSRE | 74 | Gearhart et al |

| 62 | Gupta et al | |

| 22 | Dickson et al | |

| CPRE | 80 | Grady et al |

| 74 | Hammouda et al | |

| 23 | Arab et al | |

| RSTM | 73 | Kelly et al |

| 70 | Jarzebowski et al | |

| 33–67 (female) | Cuckow et al | |

| 44–81 (male) |

Currently, these patients have excellent long-term survival, achieving urinary continence in up to 75-80% of patients with bladder exstrophy and 65-70% in cases of cloacal exstrophy;39,43,41 however, many of them require permanent urinary and intestinal diversions. Generally, sexual function is preserved, and most patients are fertile. Delivery by cesarean section is recommended in female patients who underwent surgery to avoid damage to the continence mechanisms.

References

- Gearhart JP, Gearhart JP, Rink RC. The Bladder Exstrophy–epispadias–cloacal Exstrophy Complex. J Pediatr Urol 2001: 386–415. DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4160-3204-5.00030-x.

- Siffel C, Correa A, Amar E, Bakker MK, Bermejo-Sánchez E, Bianca S, et al.. Bladder exstrophy: An epidemiologic study from the International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and Research, and an overview of the literature. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2011; 157 (4): 321–332. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30316.

- Cervellione RM, Mantovani A, Gearhart J, Bogaert G, Gobet R, Caione P, et al.. Prospective study on the incidence of bladder/cloacal exstrophy and epispadias in Europe. J Pediatr Urol 2015; 11 (6): 337.e1–337.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.03.023.

- Boyadjiev SA, Dodson JL, Radford CL, Ashrafi GH, Beaty TH, Mathews RI, et al.. Clinical and molecular characterization of the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: analysis of 232 families. BJU Int. 2004;94:1337-1343. . DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2004.05170.x..

- Männer J, Kluth D. The morphogenesis of the exstrophy-epispadias complex: a new concept based on observations made in early embryonic cases of cloacal exstrophy. Anat Embryol (Berl) 2005; 210 (1): 51–57. DOI: 10.1007/s00429-005-0008-6.

- Marshall VF, Muecke EC. Variations in exstrophy of the bladder. Plast Reconstr Surg 1962; 31 (4): 396. DOI: 10.1097/00006534-196304000-00030.

- Stephens FD, Hutson JM. Differences in embryogenesis of epispadias, exstrophy–epispadias complex and hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol 2005; 1 (4): 283–288. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.01.008.

- Ebert AK, Reutter H, Ludwig M, Rösch WH. Exstrophy-epispadias complex. Definitions 2009; 4 (23). DOI: 10.32388/7eqi40.

- Ambrose SS, O’Brien DP. Surgical Embryology of the Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. Surg Clin North Am 1974; 54 (6): 1379–1390. DOI: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)40493-7.

- Mildenberger H, Kluth D, Dziuba M. Embryology of bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg. 1988;23:166-170. . DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80150-7..

- Gearhart JP. Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology, vol. 31. 12th ed. 2021. DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4160-6911-9.00124-9.

- Ives E, Coffey R, Carter CO. A family study of bladder exstrophy. J Med Genet. 1980;17:139-141. . DOI: 10.1136/jmg.17.2.139..

- Shapiro E, Lepor H, Jeffs RD. The inheritance of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 1984;132:308-310. .

- Reutter H, Qi L, Gearhart JP, Boemers T, Ebert AK, Rösch WH, et al.. Concordance analyses of twins with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex suggest genetic etiology. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:2751-2756. . DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31975.

- Carter CO. Genetics of common single malformations. Br Med Bull. 1976;32:21-26. .

- Ludwig M, Ching B, Reutter H, Boyadjiev SA. The bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. Birth Defects Res Part A Clin Mol Teratol. 2009;85:509-22. . DOI: 10.1002/bdra.20557..

- Reutter H, Shapiro E, Gruen JR. Seven new cases of familial isolated bladder exstrophy and epispadias complex (BEEC) and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;120A:215-221. . DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.20057..

- Gambhir L, Höller T, Müller M, Schott G, Vogt H, Detlefsen B, et al.. Epidemiological survey of 214 European families with Bladder Exstrophy-Epispadias Complex (BEEC) J Urol. 2008;179:1539-1543. . DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.11.092..

- Byron-Scott R, Haan E, Chan A, Bower C, Scott H, Clark K. A population-based study of abdominal wall defects in South Australia and Western Australia. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1998;12:136-151. . DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1998.00090.x..

- Wood HM, Babineau D, Gearhart JP. In vitro fertilization and the cloacal/bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: A continuing association. J Pediatr Urol. 2007;3:305-310. . DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.10.007..

- Palmer B, Frimberger D, Kropp B. Bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex and cloacal exstrophy. Section 7.D: Developmental anomalies. Paediatric Urology Book. Paediatric Urology Department, University of Oklahoma; 2011. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-84882-132-3\\_45.

- Rösch WH, Hanisch E, Hagemann M, Neuhuber WL. The Characteristic innervation pattern of the urinary bladder in particular forms of exstrophy-epispadias-complex. BJU. 2001;87:30. .

- Schober JM, Carmichael PA, Hines M, Ransley PG. The ultimate challenge of cloacal exstrophy. J Urol. 2002;167:300-304. . DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65455-9..

- Woodhouse CRJ, Hinsch R. The anatomy and reconstruction of the adult female genitalia in classical exstrophy. BJU. 1997;79:618-622. . DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.1997.00148.x..

- Woodhouse. C.R.J.: Genitoplasty in exstrophy and epispadias. Cambridge University Press; 2006, DOI: 10.1017/cbo9780511545757.046.

- Kelly JH. Vesical exstrophy: repair using radical mobilisation of soft tissues. Pediatr Surg Int 1995; 10 (5-6): 298–304. DOI: 10.1007/bf00182207.

- Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Complete primary repair of exstrophy. J Urol. 1999; 62 (4): 415–1420. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199910000-00071.

- Groth. Bladder exstrophy consortium (MIBEC) after 5 years. AUA Chicago; 2019.

- Dickson AP. The management of bladder exstrophy: the Manchester experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2014; 9 (2): 44–250. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.11.031.

- Cuckow P, López PJ. Bladder Exstrophy Closure and Epispadias. In: Spitz L, Coran A, editors. En Operative Pediatric Surgery. 7th ed. 2013. DOI: 10.1201/b13237-101.

- Borer JG, Gargollo PC, Hendren WH, Diamond DA, Peters CA, Atala A, et al.. Early Outcome Following Complete Primary Repair Of Bladder Exstrophy In The Newborn. J Urol 2005; 174 (4 Part 2): 1674–1679. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000175942.27201.59.

- Baird AD, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Modern staged repair of bladder exstrophy: a contemporary series. J Pediatr Urol 2007. 4: 11–315. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.09.009.

- Borer JG, Vasquez E, Canning DA, Kryger JV, Mitchell ME. An initial report of a novel multi-institutional bladder exstrophy consortium: a collaboration focused on primary surgery and subsequent care. J Urol. 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.114.

- Ellison JS, Shnorhavorian M, Willihnganz-Lawson K, Grady R, Merguerian PA. A critical appraisal of continence in bladder exstrophy: Long-term outcomes of the complete primary repair. J Pediatr Urol 2016. 2 (4): 05 1–205 2057. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.005.

- Schaeffer AJ, Stec AA, Purves JT, Cervellione RM, Nelson CP, Gearhart JP. Complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy: a single institution referral experience. J Urol. 2011; 86 (3): 041–1046. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.099.

- Pathak P, Ring JD, Delfino KR, Dynda DI, Mathews RI. Complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy: a systematic review. J Pediatr Urol. 2020; 6 (2): 49–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.01.004.

- Ahn JJ, Shnorhavorian M, Katz C, Goldin AB, Merguerian PA. Early versus delayed closure of bladder exstrophy: A National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Pediatric analysis. J Pediatr Urol. 2018; 4 (1): 7 1–27 5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.11.008.

- Leclair MD, Villemagne T, Faraj S, Suply E. The radical soft-tissue mobilization (Kelly repair) for bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol. 2015; 1 (6): 64–365. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.08.007.

- Leclair MD, Faraj S, Sultan S. One-stage combined delayed bladder closure with Kelly radical soft-tissue mobilization in bladder exstrophy: preliminary results. J Pediatr Urol. 2018; 4 (6): 58–564. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.07.013.

- Baradaran N, Stec AA, Schaeffer AJ, Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Delayed primary closure of bladder exstrophy: immediate postoperative management leading to successful outcomes. Urology. 2012; 9 (2): 15–419. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2011.08.077.

- Jarzebowski AC, McMullin ND, Grover S SR, BR H, J.M.. The Kelly technique of bladder exstrophy repair: continence, cosmesis and pelvic organ prolapse outcomes. J Urol. 2009. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.083.

- Cervellione RM, Husmann DA, Bivalacqua TJ, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. Penile ischemic injury in the exstrophy/epispadias spectrum: new insights and possible mechanisms. J Pediatr Urol. 2010; 5: 50–456. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.04.007.

- Purves JT, Gearhart JP. Complications of radical soft-tissue mobilization procedure as a primary closure of exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol 2008. 1: 5–69. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.02.006.

- Maruf M, Manyevitch R, Michaud J. Urinary Continence Outcomes in Classic Bladder Exstrophy: A Long-Term Perspective. J Urol. 2020; 03 (1): 00–205. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000000505.

- Promm M, Roesch WH. Recent Trends in the Management of Bladder Exstrophy: The Gordian Knot Has Not Yet Been Cut. Front Pediatr 2019; 7. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2019.00110.

Última actualización: 2024-02-16 20:59