18: Diverticula, Urachal Anomalies, and Utricles

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 23 minutos para leer.

Urachal Anomalies

Embryology and Anatomy

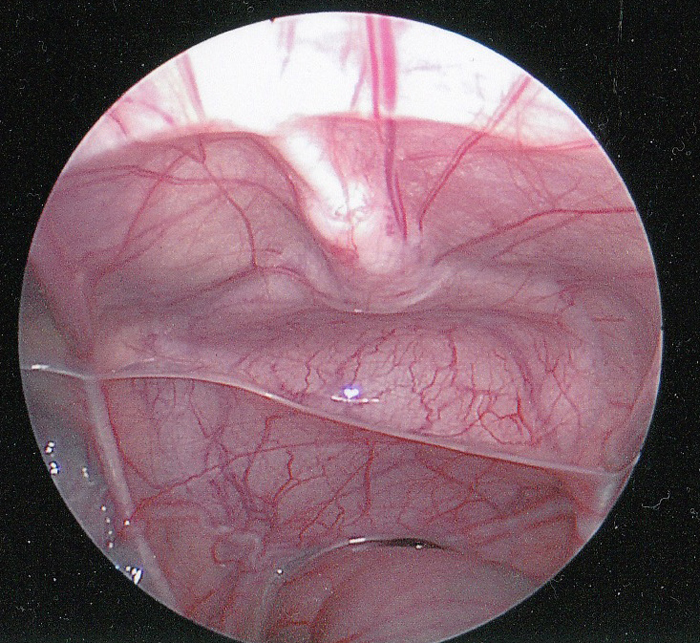

The urachus is a tubular structure that connects the allantois at the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder and is patent during gestation.1 The lumen normally closes around the twelfth week of gestation and obliterates completely. Following obliteration, all that typically remains is a fibrous cord running from the inferior aspect of the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder. The urachus is extraperitoneal and easily viewed during laparoscopic visualization of the pelvis (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Intraperitoneal laparoscopic view of the urachus. The fibrous cord of the urachus (median umbilical ligament) is shown in the midline extending down to the dome of the bladder. The rectum is inferior. The vas deferens can be seen extending laterally just above the rectum.

The urachus is covered by the folds of peritoneum to form the median umbilical ligament. Rarely, the urachus may have gaps in the fibrous cord or even complete obliteration of the cord. It is an important surgical landmark for marking the dome of the bladder to ensure proper placement of a vesicostomy.

Classification of Urachal Anomalies

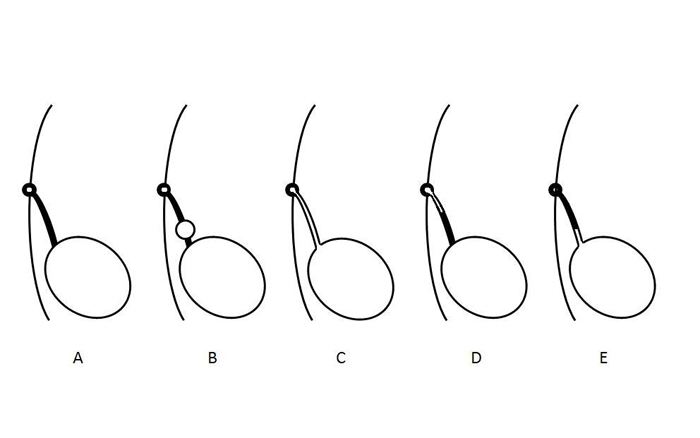

Urachal anomalies are due to failure of complete obliteration of the lumen during gestation.2 Their anatomical classification is based on the degree to which the patency of the urachus has persisted and vary from complete patency and free flow of urine to a small blind-ending sinus tract from the skin (Figure 2). A urachal cyst may be present at any location along the length of the urachus but are most commonly found near the bladder dome. A urachal diverticulum—the rarest anomaly reported—is a partial patency of the urachus draining into the dome of the bladder.

Figure 2 Diagram illustrating different types of urachal anomalies. A- Normal obliteration of the urachal lumen. B- Urachal cyst. C- Patent urachus. D- Urachal sinus. E- Urachal diverticulum. These anomalies are not mutually exclusive and may occur in combination.

The relative incidence of the different types of urachal abnormalities from several clinical series are shown in Table 1.3,4,5,6,7,8,9

Table 1 Summary of the Types and Incidence of Urachal Anomalies presenting in Children.

| Author | # Pts | Cyst | Patent | Sinus | Diverticulum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naiditch | 103 | 38 | 21 | 11 | 13 |

| Fox | 66 | 34 | 14 | 7 | 10 |

| Ashley | 46 | 25 | 6 | 14 | 1 |

| Cilento | 45 | 16 | 7 | 22 | 0 |

| Rich | 35 | 12 | 19 | 4 | 0 |

| Yiee | 31 | 19 | 7 | 5 | 0 |

| Copp | 29 | 7 | 3 | 17 | 2 |

| Total | 355 | 151 (43) | 108 (30) | 80 (23) | 26 (7) |

Interestingly there is a single case report of a patent urachus that spontaneously closed with 2 weeks of catheter drainage and persisted as a urachal diverticulum.10

Clinical Presentation

The most common presenting symptoms in children with urachal anomalies are umbilical drainage persisting weeks after delivery or a mass and/or pain due to infection.3,6,8,11 The umbilical drainage may be clear, serous, purulent, or bloody and is a clue to its cause: persistent clear fluid leakage (likely urine) in an infant is suggestive of a patent urachus while cloudy, serous, or bloody fluid is indicative of an urachal sinus or cyst. There is a bimodal age distribution with presentation at a mean of 1-3 months of age for those with urachal sinus or patency versus 3 years for those who present with a urachal cyst.8 The differential diagnosis of umbilical drainage also includes omphalitis, omphalomesenteric duct remnant, or an umbilical granuloma.6

Table 2 Presenting Symptoms in Children with Urachal Anomalies.

| Author | # Pts | Drainage | Mass/Infection | Pain | Asymptomatic | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gleason | 721 | 26 | 19 | 17 | 667 | 0 |

| Naiditch | 103 | 60 | 7 | 4 | 18 | 12 |

| Stopak | 85 | 43 | 36 | 0 | 4 | 1 |

| Dethlefs | 68 | 52 | 32 | 0 | 8 | 0 |

| Cilento | 45 | 19 | 15 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| Yiee | 37 | 20 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 1059 | 220 (21) | 117 (11) | 35 (3) | 699 (66) | 17 (2) |

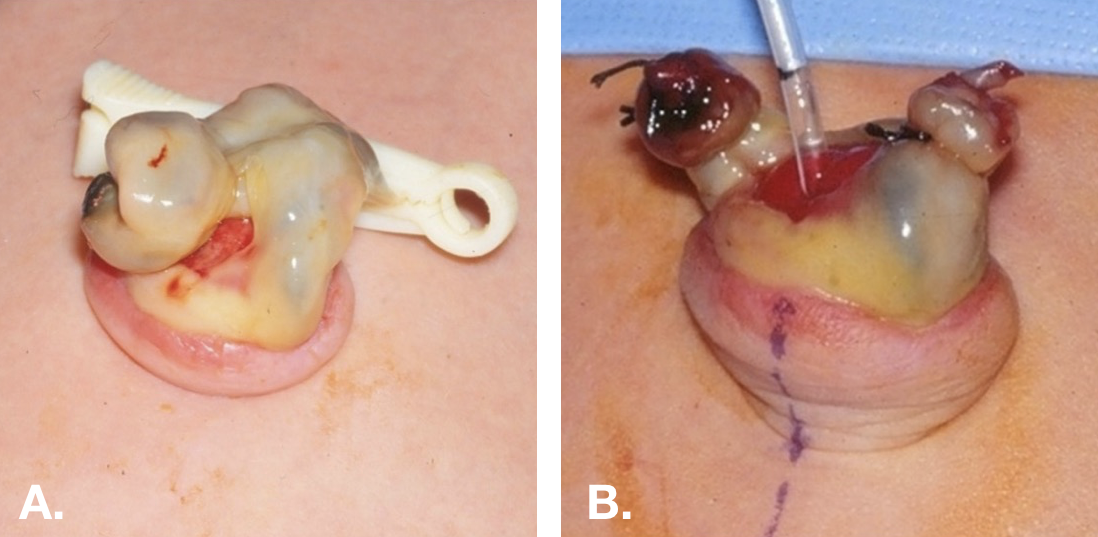

Physical examination may also be helpful. A patent urachus or urachal sinus can appear as a dimple or indentation in the base of the umbilicus (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Patent urachus in a newborn. A. Demonstrates the beefy red appearance of the umbilical end of a patent urachus. B. The umbilical skin has been everted and a small feeding has been passed through the patent urachus into the bladder.

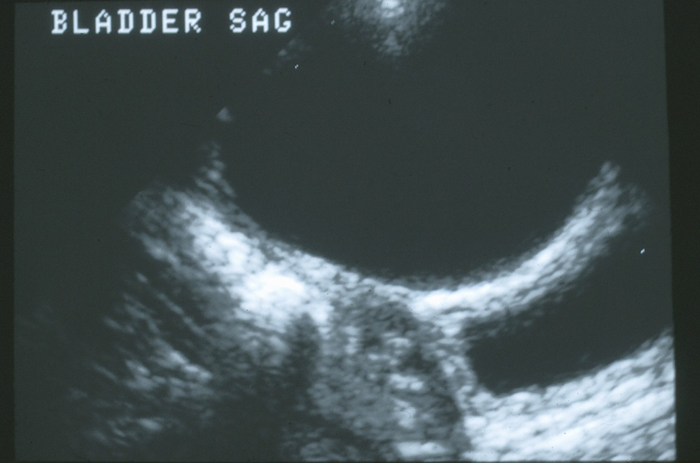

Some urachal anomalies are incidentally discovered during the routine radiographic evaluation of other disorders, such as urinary tract infections or prenatal hydronephrosis. Urachal cysts are likely to be seen during ultrasound imaging of the bladder (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Sagittal view if the dome of the bladder in the midline. There is a large anechoic urachal cyst anterior to the bladder wall.

Urachal Carcinoma

As urachal carcinoma is not a disease reported to present in children or adolescents, the treatment of this disorder will not be included in this chapter.5,12 As will be discussed in the section on management, the risk of an asymptomatic urachal anomaly developing carcinoma and, thus, the value of prophylactic excision are unknown. Risk factors for carcinoma in a urachal anomaly include size greater than 4 cm and age > 55 years. Calcifications are a common feature in carcinoma, however, the significance of calcifications in an asymptomatic benign urachal remnant is unknown.5,12 It would seem prudent to remove lesions with calcifications, given that calcifications that may be associated with chronic inflammation, which is associated with carcinogenesis.

Radiologic Evaluation

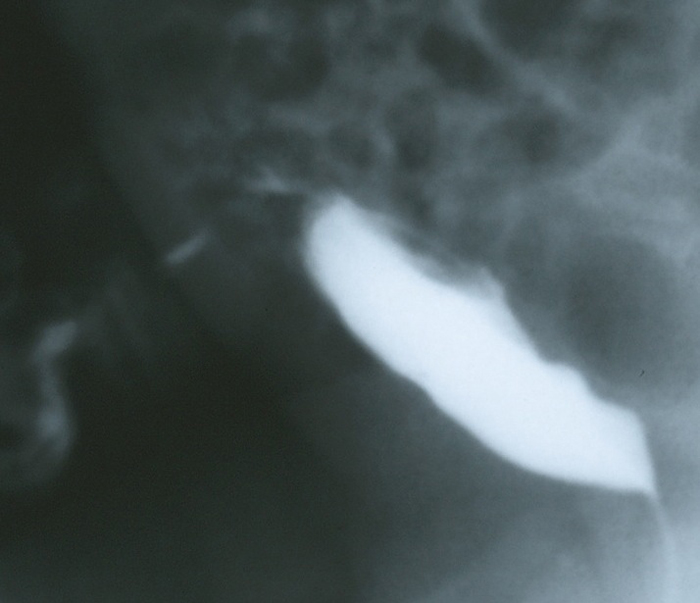

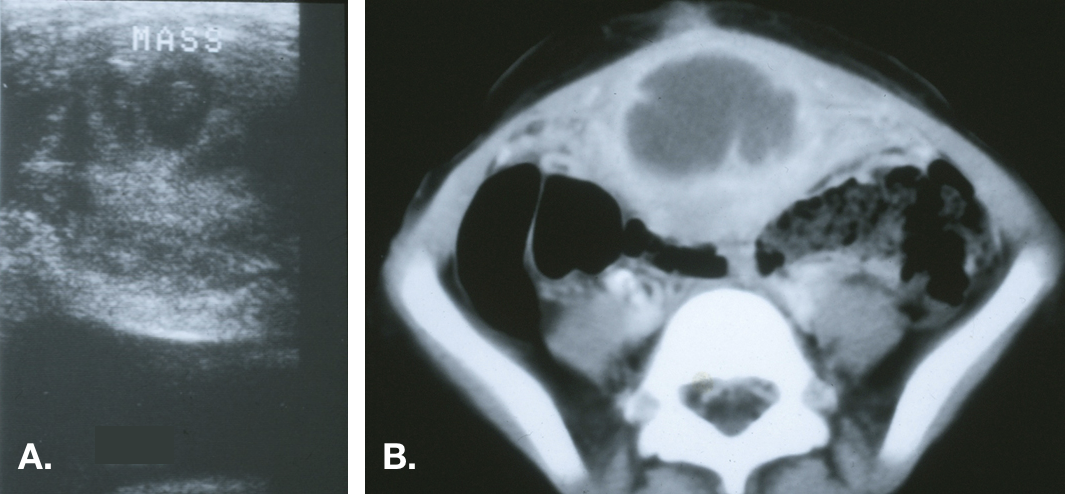

Imaging is directed by the presenting symptoms and the degree of clinical suspicion.6,8 A patent urachus that allows urine to drain freely through the umbilicus can be imaged with a high degree of sensitivity with either a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) or sinogram. Traditionally a VCUG was performed to identify the patent urachus and also provide an anatomical assessment of the bladder and evaluate for bladder outlet obstruction or vesicoureteral reflux (Figure 5). However, abdominal ultrasound is adequate for diagnosis in most patients, more widely available, less invasive, and less costly; thus, it has become the standard for diagnosis, and VCUG is reserved for complicated cases.3,13 It is important to notify the ultrasonographer of the clinical suspicion for urachal anomaly so the midline abdominal wall is thoroughly examined. Infected urachal cysts appear as large heterogenous masses with complex fluid collections (Figure 6).

Figure 5 Lateral filling view from a VCUG in an infant with copious amounts of clear fluid draining from the umbilicus. The image demonstrates contrast draining through the anterior abdominal wall from the dome of the bladder via the patent urachus.

Figure 6 Infected urachal cyst. A. Transverse view of the bladder dome in the midline demonstrating a heterogeneous echogenic mass above the bladder. B. CT scan showing the midline mass with central fluid density consistent with an abscess and inflammatory stranding of the adjacent anterior abdominal wall.

The lesions may be several centimeters in diameter and can, on occasion, spread beyond the pre-peritoneal space and perforate the peritoneal cavity.14,15

CT should not be considered an integral component of the routine workup but can detect anomalies missed by US and thus is useful in cases of high clinical suspicion without clear diagnosis (Figure 7).

Figure 7 CT scan in a patient with recurrent bloody umbilical drainage. A. Image just inferior to the umbilicus demonstrates a normal appearing urachus (fibrous cord) just inferior to the rectus muscles in the midline. B. A urachal cyst is demonstrated more inferiorly. C. The proximity of the inferior extent of the cyst and the dome of the bladder is demonstrated.

The evaluation should also include a renal ultrasound to ensure the absence of hydronephrosis or other congenital kidney anomalies.6,8,9,16 The incidence of concomitant kidney abnormalities has varied widely in published series, but given the lack of morbidity and risk with ultrasound, it is prudent to include imaging the kidneys as part of the work-up.4

Treatment

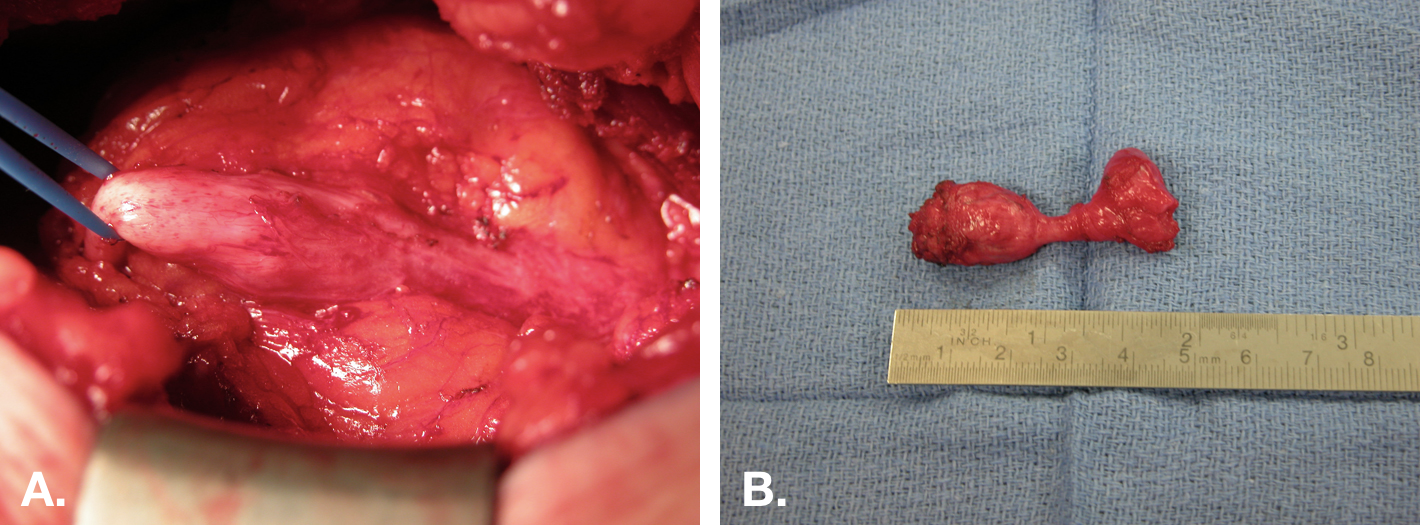

In general, symptomatic urachal remnants should be treated with surgical excision. This should include complete excision of the urachus from the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder (Figure 8).

Figure 8 Open excision of urachal cyst. A. Intra-operative view of a urachal cyst excision via an infra-umbilical midline incision. The cyst is in center with the bladder attachment to the right, and the fibrous cord extending to the umbilicus on the left. B. The specimen (cyst) after excision with the small cuff of bladder (right end of specimen).

The necessity of excising bladder mucosa with urachal cysts or sinuses that are not continuous with the bladder wall is debated.2,6,7,17,18 Infected urachal cysts present another dilemma, as the marked enlargement of the cyst due to infection and surrounding inflammation make simple excision more difficult and may increase the risk of complications. One can approach the infected urachal cyst in either a single or staged approach.7,17,19 The relative merits and risks of the two approaches are further discussed below.

Surgical excision of the urachal remnant is curative and there are no functional sequelae from its excision, as it is a vestigial remnant. The main surgical dilemma occurs in patients who present with an asymptomatic lesion that is incidentally discovered in imaging.

Conservative Management

There are limited data regarding the long-term sequelae—namely recurrent infection and development of carcinoma—of urachal anomalies left in situ. Historically, excision was favored given presumed risk of malignant transformation, however, recent publications argue for a conservative approach.10,20 Closure of the patent urachus and regression of urachal cysts—even in the setting of infection—have been reported.21,22,23 Recurrence of symptoms following percutaneous drainage of infected cysts appears to be rare.23 In one series, 92% of infants < 6 months who were observed had resolution of infection, whereas 60% who underwent excision developed a post-operative infection indicating conservative management until at least 6 months of age may be prudent.21

For infected urachal cysts, urine culture and culture of wound drainage, if present, should be obtained. The most common organism cultured from infected urachal cysts is Staphylococcus aureus (Table 3).5,21,18,20 If the patient is stable, afebrile, non-toxic, without peritoneal signs, spreading cellulitis, or signs of fasciitis, initial management with antibiotics alone can be considered.

Table 3 Microbial Species cultured from Infected Urachal Remnants. * E Coli-3, Citrobacter, Enterococcus, and Proteus.

| Author | # Pts | S. Aureus | Strep sp | Other * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stopak | 16 | 9 | 0 | 2 |

| McCollum | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Minevich | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Ashley | 9 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| Galati | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Newman | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 53 | 38 (72) | 2 (4) | 8 (15) |

For unstable patients or those that fail conservative management, the infected cyst may be managed via initial complete surgical excision or percutaneous (US or CT guided) or open drainage. In the single-stage excision of the infected urachus, the margins of resection will be larger and result in larger soft tissue defect and the extent of the inflammation can extend intraperitoneal, which puts the abdominal viscera at risk. There is a small but significant risk of an enterocutaneous fistula and a higher rate of wound complications after primary excision of an infected urachal cyst compared to drainage.21,18,19,24 Percutaneous drains may incompletely drain multiloculated fluid collections. Traditionally, all cysts were excised following resolution of inflammation in a staged procedure. Several recent studies have demonstrated that recurrent infection is uncommon and, thus, delayed excision may not be required.

Laparoscopic Excision of the Urachus

In this era of minimally invasive surgery, multiple reports of laparoscopic, and more recently, robotic-assisted laparoscopic resection of urachal remnants in children have emerged.25,26,27 Laparoscopic single site surgery has been reported as well.28 The main advantage of robotic technique is the ease of suturing compared to pure laparoscopy.27 Visualization is excellent with a laparoscopic approach for the bladder but can be more challenging at the umbilicus if the ports are not carefully placed. The urachus should be resected from the base of the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder. Again, there is controversy as to whether or not complete resection requires excision of the dome of the bladder.25,26

Port placement is an important consideration.26 Since the urachus originates at the umbilicus, this cannot be used as a port site. The most common site for the camera is supra-umbilical (usually 1–2 cm). This gives enough working space to visualize the dissection from the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder. Working ports should be placed laterally on either side, usually at the level of the umbilicus. Alternatively, lateral working ports and camera placement (on either the right or left side of the abdomen) offers lateral visualization of the urachus and keeps all the ports infra-umbilical in location. The lateral port configuration will make suturing the bladder closure more difficult due to the angle.

Figure 9 Diagram of possible port placement for urachal remnant excision. Unlike the set-up for most laparoscopic surgeries, the umbilicus cannot be used as a port site as it is the origin of the urachus and must be visualized in the dissection.

Open Excision of the Urachus

In infants and small children complete resection of the urachus can easily be accomplished through a small incision. It can be oriented in either a transverse or vertical midline. For infants, a small 1-1.5 cm incision midway between the pubis and umbilicus will give access to the urachus and allow complete resection from the umbilicus to the dome of the bladder with excellent exposure of bladder dome for closure. This small incision is comparable to the size of incision needed for the 12 mm camera port of the surgical robot and keeps the procedure entirely extra-peritoneal, eliminating potential intra-abdominal complications. In older or obese children or adolescents, it is prudent to make a vertical midline incision. If there is trouble with exposure, the incision can be extended up toward the umbilicus or down toward the bladder to facilitate complete removal of the urachus in these patients. Complication rates for simple excision are very low and the surgery can either be performed as an outpatient or with a short hospital stay if a catheter is left in place. Urine leaks or wound complications are more commonly associated with single-stage excision of infected cysts and not simple excision.18,19

Key Points

- Urachal anomalies most commonly present as umbilical drainage persisting weeks after delivery or umbilical mass and/or pain due to infection.

- The differential diagnosis of umbilical drainage includes urachal anomaly, omphalitis, omphalomesenteric duct remnant, or an umbilical granuloma.

- The absolute risk of an asymptomatic urachal anomaly developing carcinoma is unknown. Risk factors for carcinoma in a urachal anomaly include size greater than 4 cm and age >55 years.

- Abdominal ultrasound is adequate for diagnosis of urachal anomaly in most patients. Workup should include renal ultrasound to evaluate for congenital kidney anomalies.

- Symptomatic urachal remnants should be excised via open, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach. If using a laparoscopic or robotic approach, the umbilicus cannot be used as a port site.

- Uncomplicated infections of urachal cysts can be treated conservatively with antibiotics ± percutaneous drainage. Immediate excision carries significant risk of post-operative infection. Delayed excision is reasonable but may not be necessary as closure of remnants/cyst is possible and recurrent infection rare especially in children <6 months old.

Prostatic Utricle

Embryology and Anatomy

In male fetuses, the production of Müllerian inhibiting substance (MIS) by Sertoli cells signals the rapid regression of the paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts—which in females become the Fallopian tubes, oviduct, uterus, and upper 2/3 of the vagina—in the 8-10th weeks of gestation. The prostatic utricle is a small remnant of the paramesonephric ducts that persists in males as an expansion of the prostatic urethra.1 The utricle arises from the midline of the prostate at the cranial aspect of the verumontanum.

Clinical Presentation

Prostatic utricles (PU) are not clinically significant unless complete regression was impaired and the utricle maintains a dilated, cystic appearance, acting as a diverticulum of the prostatic urethra. Utricle enlargement is associated with hypospadias, cryptorchidism, disorders of sexual differentiation, and unilateral renal agenesis.29,30,31,32,33,34 Case series indicate PU dilation occurs in 10-33% of patients with proximal hypospadias, with incidence increasing with severity of hypospadias defect.30,32 In one series of boys with normal external genitalia with symptomatic PU, unilateral renal agenesis was found in nearly one-third of cases.33

PU may be asymptomatic, cause symptoms related to obstruction or urinary stasis—recurrent urinary tract infections, epidydimo-orchitis, urethral discharge, retention, stone formation, or post-void dribbling—or may present with abdominal pain, hematuria, or hematospermia.31,33,35 Rarely, malignant transformation has been reported.33,34,36

Dilation of the prostatic utricle may impede catheterization of males with hypospadias—difficult catheterization may be the presenting or only symptom of prostatic utricle in these patients. Large utricles may be palpable inferior or posterior to the bladder on digital rectal exam.31,33,35,37

Differential diagnosis for prostatic utricles includes müllerian duct cyst (not continuous with prostatic urethra), bladder diverticulum, urachal cyst, and seminal vesicle cyst.33,38

Table 4 Presenting symptoms of patients with prostatic utricles

| Author | # Pts | UTI | LUTS | Retention | Epididymitis/ Scrotal pain | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desautel | 26 | 6 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 |

| Liu | 22 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Dai | 15 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 4 |

| Jia | 14 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Babu | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 84 | 31 (37) | 13 (15) | 16 (19) | 20 (24) | 5 (6) |

Radiologic Evaluation

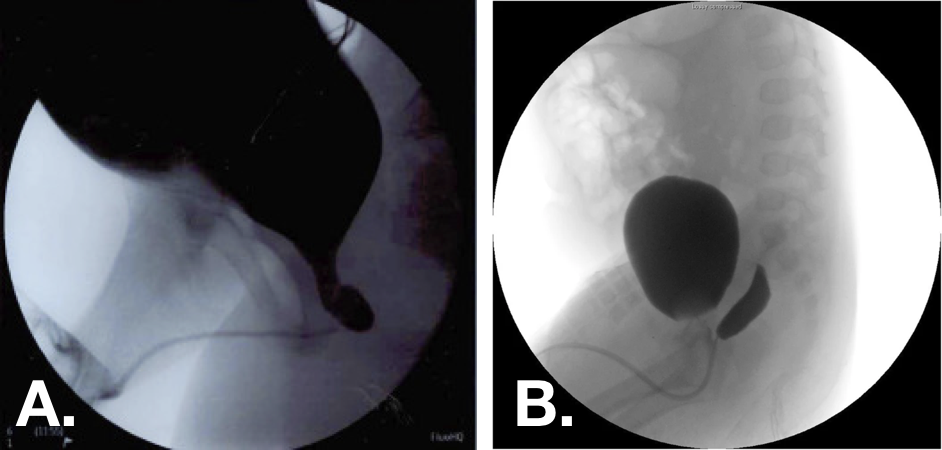

Diagnosis is often established via retrograde urethrogram (RUG) or voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) as these modalities allow visualization of utricle orifice in relation to the urethra and bladder. However, transabdominal ultrasonography is nearly as sensitive as RUG and may be adequate in detecting utricles that are large enough to warrant intervention.30,39 Utricles may be missed on imaging due to incomplete filling. Cross-sectional imaging may be performed and can aid in operative planning but is not necessary for diagnosis. Utricles may be classified on imaging as follows:29

- Grade 0 – confined to the verumontanum

- Grade 1 – extends to or below the bladder neck (Image 1)

- Grade 2 – extends proximal to the bladder neck (Image 2)

- Grade 3 – opens distal to the external urethral sphincter

Figure 10 Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) images demonstrating grade 1 (left) and grade 2 (right) prostatic utricles.30,33

Management

Successful conservative management of symptomatic utricles has not been well described and would generally require frequent or long-term prophylactic antibiosis for recurrent infection.33 A variety of successful surgical approaches have been described with complete excision of the utricle offering definitive management. For utricles with very small orifices, transrectal ultrasound guided aspiration and transurethral catheterization and aspiration, orifice incision, and fulguration have been all reported.31,33,35,40 These approaches are minimally invasive but confer higher incidence of symptom recurrence than excision. Open, laparoscopic, and robotic-assisted approaches to excision have all been described, and there is no consensus regarding optimum approach. The robotic approach may be advantageous due to the difficult location of the utricle. Utricles may be accessed via extraperitoneal, extravesical, transvesical, posterior sagittal, or perineal approaches.31,33,35,37,41 Concomitant cystoscopy can help define the limits of dissection in laparoscopic procedures.37,41 Reported conversions from laparoscopic to open approaches for utricle excision are uncommon.

The key principles of excision regardless of approach are adequate dissection, excision, and water-tight closure of the utricle orifice and avoidance of injury to the pelvic nerves, vas deferens, seminal vessels, seminal colliculi, and rectum.

Table 5 Surgical approaches to prostatic utricle excision and post-operative recurrence of presenting symptoms

| Approach | Endoscopic | Endoscopic | Open | Open | Laparoscopic | Laparoscopic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Cases | Recurrence | Cases | Recurrence | Cases | Recurrence |

| Liu | 3 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Desautel | 2 | 1 | 13 | 0 | – | – |

| Dai | 13 | 5 | – | – | 4 | 0 |

| Jia | – | – | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Babu | 7 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Yeung | – | – | – | – | 4 | 0 |

| Bayne | – | – | – | – | 4 | 0 |

| Total | 25 | 8 (32) | 34 | 4 (12) | 23 | 1 (4) |

Key Points

- The prostatic utricle is a small remnant of the paramesonephric ducts that persists in males as an expansion of the prostatic urethra.

- Utricle enlargement is associated with hypospadias, cryptorchidism, disorders of sexual differentiation, and unilateral renal agenesis.

- Prostatic utricles may be asymptomatic, cause symptoms related to obstruction or urinary stasis, or may present with abdominal pain, hematuria, or hematospermia.

- Dilation of the prostatic utricle may impede catheterization of males with hypospadias.

- Symptomatic prostatic utricles may be excised by open, laparoscopic, or robotic-assisted approach.

Bladder Diverticula

Bladder diverticula are rare in the pediatric population, occurring in 1.7% of patients.42 Diverticula may be either congenital or acquired; congenital bladder diverticula are much more common in the pediatric population.43

Congenital Diverticula

Congenital diverticula are thought to be a result of a defect in the detrusor muscle. Ninety percent develop around Waldeyer’s sheath, which contains the ureter, and are known as Hutch diverticula.44 They may be classified as periureteral (diverticulum near but not involving ureteral orifice) or paraureteral (ureteral orifice involved in diverticulum).44 Distortion of the bladder wall and muscular tunnel of the ureter predispose children with these diverticula to vesicoureteral reflux. Congenital diverticula not associated with the ureter develop in the posterolateral bladder.43

Congenital bladder diverticula are associated with genetic syndromes that impact connective tissue development: Ehlers-Danlos types IV, V, IX; Menkes syndrome; Williams-Beuren syndrome, and fetal alcohol syndrome.41,44,45 Unlike acquired diverticula, congenital diverticula are found in smooth walled bladders that typically demonstrate normal voiding mechanics, are solitary defects, and are not associated with increased risk of malignancy.43 Congenital diverticula occur more often in males and are generally larger than those acquired by neurogenic bladder dysfunction.43

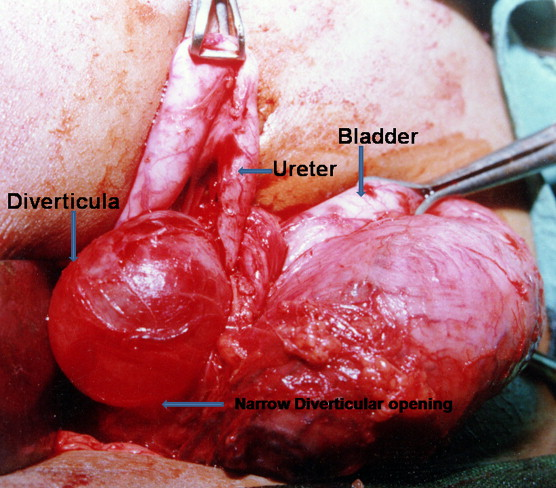

Figure 11 Intraoperative demonstration of large paraureteral bladder diverticulum with proximal dilation and medial displacement of ureter.46

Acquired Diverticula

Acquired or secondary diverticula develop because of neurogenic or obstructive pathology in the lower urinary tract. Though the most common type of diverticulum in adults, secondary diverticula are rare in pediatric patients and signal severe lower tract dysfunction.43 They are more likely to be found near the bladder dome, may be multiple, and are more likely to be seen in a trabeculated bladder. Acquired diverticula in general are associated with neurogenic bladder and bladder outlet obstruction, and in pediatric patients can be seen with posterior urethral valves & prune belly syndrome.42,43

Clinical Presentation

Bladder diverticula in children most often present with UTI secondary to urinary stasis within the diverticulum or are discovered during work-up for hydronephrosis or febrile UTI and suspected vesicoureteral reflux.44,46 Upper urinary tract abnormalities can be found in 16-30% of cases.44 Less common presenting symptoms include irritative voiding symptoms, hematuria, abdominal distention and pain, enuresis, bladder stones, and outlet obstruction due to distortion of the bladder neck.46,47,48 Rarely, bladder diverticula can present with complete ureteral obstruction or intra- or extraperitoneal perforation.49,50,51,52,53,54

Most patients with congenital bladder diverticula are asymptomatic, and—though far less commonly than acquired diverticula—may be incidentally diagnosed in adults.

Given the association with various genetic conditions, the frequency of upper tract abnormalities, and the possibility of underlying neurogenic or obstructive disease, it has been proposed by some that all children with bladder diverticula be tested for chromosomal abnormalities.42 Routine genetic testing is not currently recommended for patients with single congenital bladder diverticulum.44

Table 6 Presenting symptoms and associated findings of children with bladder diverticula

| Authors | # Pts | UTI | LUTS | Retention | Other | VUR | Hydro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander | 47 | 26 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 32 | 19 |

| Evangilidis | 21 | 19 | 12 | 0 | – | – | – |

| Marte | 16 | 15 | 9 | 0 | 6 | 7 | – |

| Bhat | 12 | 5 | – | 12 | 4 | 9 | 5 |

| Macedo | 10 | 5 | 3 | 1 | – | – | 4 |

| Total | 106 | 70 (66) | 26 (25) | 13 (12) | 12 (11) | 48 (45) | 28 (26) |

Radiologic Evaluation

Bladder diverticula are often first detected on bladder ultrasound as a hypoechoic cyst off the posterolateral bladder wall. The differential diagnosis for suspected diverticulum on imaging includes urachal cyst, everting ureterocele, ectopic ureter, bladder herniation into inguinal hernia, and bladder duplication.44 Voiding cystourethrogram with lateral and oblique views is the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of bladder diverticulum and allows simultaneous evaluation for VUR.43 Particularly in cases without VUR, intravenous pyelogram or CT or MR urogram may be used to clarify the anatomic relationship between the diverticulum and the ureter.44 The upper tracts of children with bladder diverticula should be evaluated for hydroureteronephrosis.

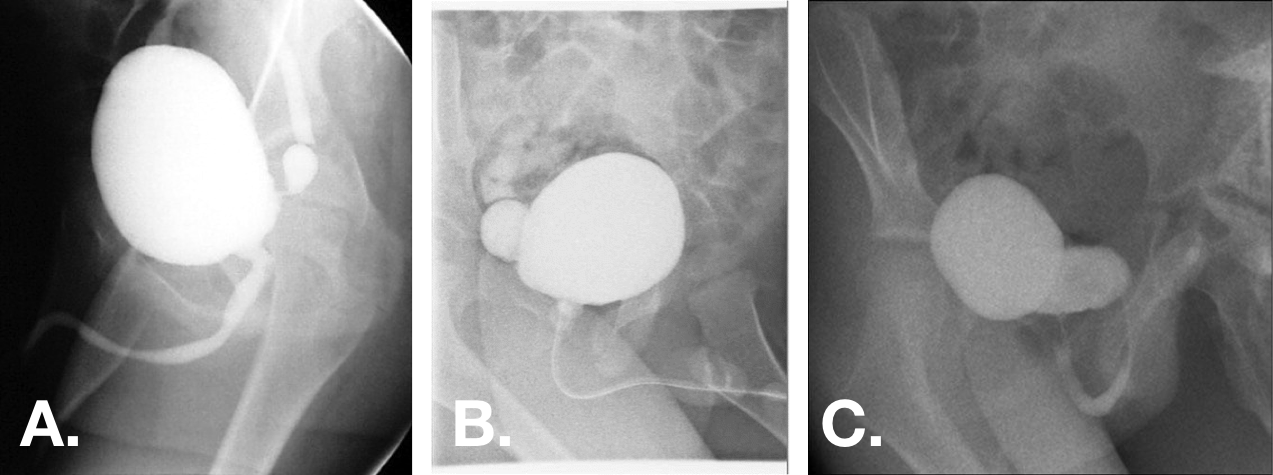

Figure 12 Congenital bladder diverticula seen on VCUG oblique views. Diverticula may range from small with very narrow necks to larger than bladder with broad-based openings.44,47,55

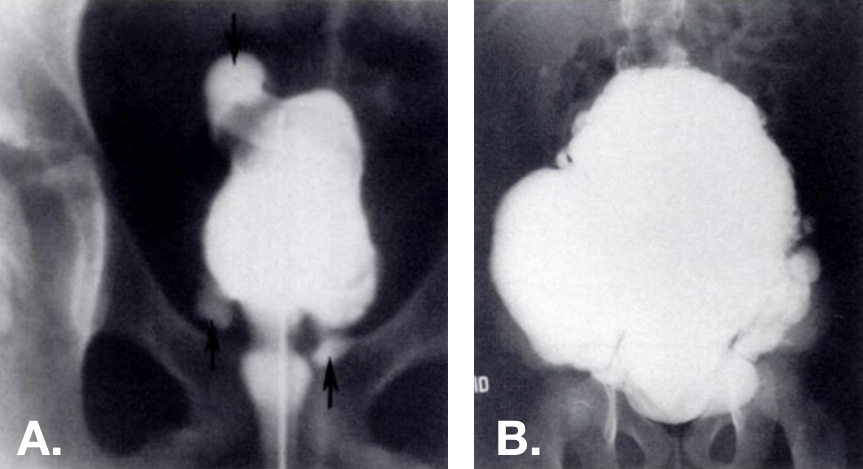

Figure 13 Acquired diverticula seen on VCUG. Multiple diverticula present at various locations—including at the bladder dome—in trabeculated bladders. Photo on the right is from a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.42

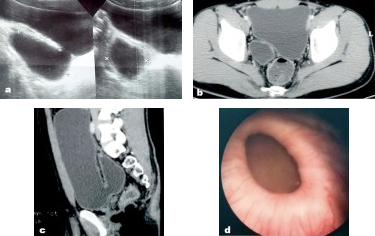

Figure 14 Congenital bladder diverticulum as seen on ultrasound, pelvic CT, and cystoscopy.56

Urodynamic studies may be considered in patients with bladder diverticula if underlying lower tract dysfunction is suspected or if presence of a diverticulum does not adequately explain the patient’s presenting symptoms. Detrusor overactivity can be seen in around half of these patients, possibly secondary to hypotonia within and around the diverticulum and chronic urinary stasis.44,48 Diverticula complicate interpretation of cystometrogram, as they sink intravesical pressure. Stasis of urine within the diverticulum and associated VUR may also complicate results.44

Endoscopic evaluation may help clarify anatomy and is recommended during surgical intervention but is not necessary for diagnosis of bladder diverticulum.

Indications for Repair

Though bladder diverticula do not resolve without intervention, not all patients require surgery. Adequate treatment of UTI and voiding dysfunction may resolve symptoms in patients with small, uncomplicated diverticula.44 For those with refractory symptoms or complicated diverticula, surgical excision is generally curative, and ureteral reimplantation can be performed simultaneously as necessary. Generally accepted indications for surgery include the following:43,44

- Voiding symptoms refractory to medical management

- Diverticulum > 3cm

- Frequent UTI

- Complicated VUR

- Urinary retention

- Upper tract obstruction or deterioration

- Bladder stones

- Rupture of diverticulum

Unlike in adults, malignant degeneration of the epithelium associated with pediatric bladder diverticula is generally not seen; however, any concern for malignancy would necessitate surgical intervention.43

Prior to any operative intervention, voiding dysfunction should be evaluated and managed to isolate symptoms related to diverticulum and their evolution post-operatively. Associated pathology such as detrusor underactivity, bladder outlet obstruction, or spinal cord dysraphism should be addressed prior to diverticulectomy.

Surgical intervention should be carefully considered in patients with underlying connective tissue disorders, as recurrence is likely in this population.44,53

Operative Approaches

Bladder diverticulectomy may be performed endoscopically or via trans- or extravesical open or minimally invasive approaches. Transvesical and extravesical approaches mirror those used for ureteral reimplantation, and reimplantation may be performed as part of the procedure if necessary due to situation of the diverticulum or if indicated due to severe associated VUR. Cystoscopic evaluation of the diverticular opening relative to the ureteral orifice is recommended as part of operative planning. Multiple case series have reported complete resolution of symptoms—or marked reduction in voiding dysfunction symptoms—as well as VUR following diverticular excision regardless of approach.57,55 Occlusion of paraureteral diverticular opening via subureteral injection of bulking agents has been reported, though data on long-term efficacy are limited.58,59 One comparison of endoscopic, intra-, and extravesical approaches demonstrated successful resolution of VUR in 79, 91, and 80% of cases respectively.59

Important surgical considerations regardless of approach are culture-guided peri-operative antimicrobial prophylaxis, avoidance of injury or devascularizaion of the ureter or vas deferens, avoidance of rectal injury in repair of large posterior diverticula, and post-operative bladder decompression.44

Key Points

- Bladder diverticula in children may be congenital—due to defect in the detrusor muscle, most often around Waldeyer’s sheath (Hutch diveritcula)—or acquired due to neurogenic or obstructive lower tract pathology.

- Distortion of the bladder wall and muscular tunnel of the ureter by Hutch diverticula predispose children to vesicoureteral reflux.

- Bladder diverticula in children most often present with UTI secondary to urinary stasis within the diverticulum or are discovered during work-up for hydronephrosis or febrile UTI and suspected vesicoureteral reflux. The majority of diverticula are asymptomatic.

- Voiding cystourethrogram with lateral and oblique views is the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of bladder diverticulum and allows simultaneous evaluation for VUR.

- For those with refractory symptoms or complicated diverticula, surgical excision may be performed via transvesical or extravesical approach. Ureteral reimplantation can be performed simultaneously as necessary.

- Prior to any operative intervention, voiding dysfunction should be evaluated and managed.

Summary

Urachal anomalies may present in various forms and most often cause drainage from the umbilicus or infection. Anomalies may be managed conservatively and can spontaneously resolve. Infected cysts may be percutaneously drained, and any symptomatic anomaly can be excised via open or laparoscopic approaches. The risk of malignant transformation of asymptomatic urachal anomalies in children is unknown.

Prostatic utricle dilation is associated with hypospadias and other genitourinary anomalies and may be asymptomatic or cause symptoms related to outlet obstruction and urinary stasis. Utricles may be diagnosed via RUG, VCUG, or US. For symptomatic patients, excision may be accomplished via endoscopic, open, or laparoscopic approaches, with endoscopic management conferring a higher risk of recurrence.

Pediatric bladder diverticula may be either congenital or acquired. Congenital diverticula are due to detrusor defects near the ureteral sheath and are associated with VUR as well as connective tissue disorders. Diverticula are often asymptomatic but may cause infection, irritative voiding symptoms, retention, or abdominal pain and are often associated with detrusor overactivity. Acquired diverticula are secondary to lower urinary tract obstruction or neurogenic bladder. Indications for operative repair include refractory or severe symptoms, size >3cm, and associated urinary tract dysfunction. Intervention should be preceded by management of any other lower tract pathology. There is no consensus regarding operative approach, and ureteral reimplantation is often performed simultaneously.

References

- Jm P. Embryology of the genitourinary tract. Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2016, DOI: 10.1201/b13795-15.

- MacNeily AE, Koleilat N, Kiruluta HG, Homsy YL. Urachal abscesses: Protean manifestations, their recognition, and management. Urology 1992; 40 (6): 530–535. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(92)90409-p.

- Naiditch JA, Radhakrishnan J, Chin AC. Current diagnosis and management of urachal remnants. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48 (10): 2148–2152. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.02.069.

- Fox JA, M.S. R, JC G, CF A, RA H, JC V, et al.. Vesicoureteral reflux in children with urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (6): 632–635. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.04.001.

- Ashley RA, Inman BA, Routh JC, Rohlinger AL, Husmann DA, Kramer SA. Urachal Anomalies: A Longitudinal Study of Urachal Remnants in Children and Adults. J Urol 2007; 178 (4s): 1615–1618. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.194.

- Cilento BG, Bauer SB, Retik AB, Peters CA, Atala A. Urachal anomalies: defining the best diagnostic modality. Urology 1998; 52 (1): 120–122. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00161-7.

- Rich RH, Hardy BE, Filler RM. Surgery for Anomalies of the Urachus. J Urol 1983; 131 (3): 616–616. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50535-2.

- Yiee JH, Garcia N, Baker LA, Barber R, Snodgrass WT, Wilcox DT. A diagnostic algorithm for urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Urol 2007; 3 (6): 500–504. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.07.010.

- Copp HL, Wong IY, Krishnan C, Malhotra S, Kennedy WA. Clinical Presentation and Urachal Remnant Pathology: Implications for Treatment. J Urol 2009; 182 (4s): 1921–1924. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.026.

- Cuda SP, Vanasupa BP, Sutherland RS. Nonoperative management of a patent urachus. Urology 2005; 66 (6): 1320.e7–1320.e9. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.121.

- Gleason JM, Bowlin PR, Bagli DJ, Lorenzo AJ, Hassouna T, Koyle MA, et al.. A Comprehensive Review of Pediatric Urachal Anomalies and Predictive Analysis for Adult Urachal Adenocarcinoma. J Urol 2015; 193 (2): 632–636. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.09.004.

- Stopak JK, Azarow KS, Abdessalam SF, Raynor SC, Perry DA, Cusick RA. Trends in surgical management of urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Surg 2015; 50 (8): 1334–1337. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.04.020.

- Dethlefs CR, Abdessalam SF, Raynor SC, Perry DA, Allbery SM, Lyden ER, et al.. Conservative management of urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Surg 2019; 54 (5): 1054–1058. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.039.

- Sheldon CA, Clayman RV, Gonzalez R, Williams RD, Fraley EE. Malignant Urachal Lesions. J Urol 1984; 131 (1): 1–8. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50167-6.

- Oestreich AE. Urachal anomalies in children: the vanishing relevance of the preoperative voiding cystourethrogram. Yearbook of Diagnostic Radiology 2005; 2007 (12): 174–175. DOI: 10.1016/s0098-1672(08)70123-1.

- Lewis JB, Morse JW, Eyolfson MF, Schwartz SL. Spontaneous Rupture of a Vesicourachal Diverticulum Manifesting as Acute Abdominal Pain. Acad Emerg Med 1996; 3 (12): 1140–1143. DOI: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1996.tb03375.x.

- OGBEVOEN JUSTINO, JAFFE DAVIDM, LANGER JACOBC. Intraperitoneal rupture of an infected urachal cyst: A rare cause of peritonitis in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 1996; 12 (1): 41–43. DOI: 10.1097/00006565-199602000-00012.

- GONZ??LEZ RICARDO, De FILIPPO ROGER, JEDNAK ROMAN, BARTHOLD JULIASPENCER. Urethral Atresia: Long-term Outcome In 6 Children Who Survived The Neonatal Period. J Urol 2001: 2241–2244. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200106001-00006.

- Mesrobian H-GO, Zacharias A, Balcom AH, Cohen RD. Ten Years of Experience With Isolated Urachal Anomalies in Children. J Urol 1997; 158: 1316–1318. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00173.

- McCollum MO, MacNeily AE, Blair GK. Surgical implications of urachal remnants: Presentation and management. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38 (5): 798–803. DOI: 10.1016/jpsu.2003.50170.

- Minevich E, W.J. L, A.G.. The infected urachal cyst: Primary excision versus a staged approach. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 33 (1): 147. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90408-0.

- Newman BM, Karp MP, Jewett TC, Cooney DR. Advances in the management of infected urachal cysts. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21 (12): 1051–1054. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3468(86)90006-0.

- Yoo KH, Lee S-J, Chang S-G. Treatment of Infected Urachal Cysts. Yonsei Med J 2006; 47 (3): 423. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2006.47.3.423.

- Galati VG, D.B. R, F.. Management of Urachal Remnants in Early Childhood. Yearbook of Diagnostic Radiology 2008; 2009: 154–155. DOI: 10.1016/s0098-1672(09)79312-9.

- Nogueras-Ocaña M, Rodríguez-Belmonte R, Uberos-Fernández J, Jiménez-Pacheco A, Merino-Salas S, Zuluaga-Gómez A. Urachal anomalies in children: Surgical or conservative treatment? J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (3): 522–526. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.11.010.

- Lipskar AM, Glick RD, Rosen NG, Layliev J, Hong AR, Dolgin SE, et al.. Nonoperative management of symptomatic urachal anomalies. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45 (5): 1016–1019. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.031.

- Stone NM, Garden RJ, Webert H. Laparoscopic excision of a urachal cyst. Urology 1995; 45 (1): 161–164. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(95)97824-0.

- OKEGAWA TAKATSUGU, ODAGANE AKIHIRO, NUTAHARA KIKUO, HIGASHIHARA EIJI. Laparoscopic management of urachal remnants in adulthood. Int J Urol 2005; 13 (12): 1466–1469. DOI: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01613.x.

- Yamzon J, K.P. DF, RE C, AY H, BE K, C.J.. V1710 Pediatric Robotic-assisted Laparoscopic Urachal Cyst And Bladder Cuff Excision. J Urol 2008; 185 (4s): 2385–2388. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.2035.

- Patrzyk M, Glitsch A, Schreiber A, Bernstorff W von, Heidecke C-D. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery as an option for the laparoscopic resection of an urachal fistula: first description of the surgical technique. Surg Endosc 2010; 24 (9): 2339–2342. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-010-0922-4.

- IKOMA F, SHIMA H, YABUMOTO H. Classification of Enlarged Prostatic Utricle in Patients with Hypospadias. Br J Urol 1985; 57 (3): 334–337. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1985.tb06356.x.

- Aktuğ T, Ekberli\. G. Re: The prostatic utricle: an under-recognized condition resulting in significant morbidity in boys with both hypospadias and normal external genitalia. J Pediatr Urol 2017; 15 (4): 425. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.03.030.

- Dai L-N, He R, Wu S-F, Zhao H-T, Sun J. Surgical treatment for prostatic utricle cyst in children: A single-center report of 15 patients. Int J Urol 2021; 28 (6): 689–694. DOI: 10.1111/iju.14543.

- Devine CJ, Gonzalez-Serva L, Stecker JF, Devine PC, Horton CE. Utricular Configuration in Hypospadias and Intersex. J Urol 1980; 123 (3): 407–411. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)55959-5.

- Liu B, He D, Zhang D, Liu X, Lin T, Wei G. Prostatic utricles without external genital anomalies in children: our experience, literature review, and pooling analysis. BMC Urol 2019; 19 (1): 21. DOI: 10.1186/s12894-019-0450-z.

- Farikullah J, Ehtisham S, Nappo S, Patel L, Hennayake S. Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome: lessons learned from managing a series of eight patients over a 10-year period and review of literature regarding malignant risk from the Müllerian remnants. BJU Int 2012; 110 (11c): E1084–e1089. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2012.11184.x.

- Desautel MG, Stock J, Hanna MK, REMNANTS MULLERIANDUCT. Müllerian Duct Remnants. J Urol 1999; 162 (3, Part 2): 1014. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199909000-00013.

- Jia W, L.G. Z, L W, Y F, W H, J X, et al.. Comparison of laparoscopic excision versus open transvesical excision for symptomatic prostatic utricle in children J Pediatr Surg. 2016; 51 (10): 1597–1601. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.06.004.

- Babu R, Chandrasekharam VVS. Cystoscopic Management of Prostatic Utricles. Urology 2021; 149: e52–e55. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.09.005.

- Nallabothula AK, Yatam LS, Ayapati T, Bodagala VD. Large Prostatic Utricle With Transitional Cell Carcinoma in an Adult. Urology 2017; 102: e5–e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.12.048.

- Yeung CK, Sihoe JDY, Tam YH, Lee KH. Laparoscopic excision of prostatic utricles in children. BJU Int 2001; 87 (6): 505–508. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00132.x.

- Johnson D, Parikh K, Schey W, Mar W. MRI in Diagnosis of a Giant Prostatic Utricle. Case Rep Radiol 2014; 2014: 1–3. DOI: 10.1155/2014/217563.

- Kojima Y, Hayashi Y, Maruyama T, Sasaki S, Kohri K. Comparison between ultrasonography and retrograde urethrography for detection of prostatic utricle associated with hypospadias. Urology 2001; 57 (6): 1151–1155. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)00954-2.

- Bayne AP, Austin JC, Seideman CA. Robotic assisted retrovesical approach to prostatic utricle excision and other complex pelvic pathology in children is safe and feasible. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (5): 710–715. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.08.004.

- Blane CE, Zerin JM, Bloom DA. Bladder diverticula in children. Radiology 1994; 190 (3): 695–697. DOI: 10.1148/radiology.190.3.8115613.

- Es R. Bladder and female urethral diverticula. Elsevier: Philadelphia; 2017, DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4160-6911-9.00078-5.

- Psutka SP, Cendron M. Bladder diverticula in children. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (2): 129–138. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.02.013.

- Sammour Z, Gomes C, Bessa J, Pinheiro M, Kim C, Sacomani C, et al.. 1622 Congenital Genitourinary Abnormalities In Children With Williams-beuren Syndrome. J Urol 2014; 187 (4s): 804–809. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.02.1417.

- Bhat A, Bothra R, Bhat MP, Chaudhary GR, Saran RK, Saxena G. Congenital bladder diverticulum presenting as bladder outlet obstruction in infants and children. J Pediatr Urol 2012; 8 (4): 348–353. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.07.001.

- Alexander RE, Kum JB, Idrees M. Bladder Diverticulum: Clinicopathologic Spectrum in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr Dev Pathol 2012; 15 (4): 281–285. DOI: 10.2350/12-02-1154-oa.1.

- Evangelidis A, Castle EP, Ostlie DJ, Snyder CL, Gatti JM, Murphy JP. Surgical management of primary bladder diverticula in children. J Pediatr Surg 2005; 40 (4): 701–703. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.01.003.

- Marte A, Cavaiuolo S, Esposito M, Pintozzi L. Vesicoscopic Treatment of Symptomatic Congenital Bladder Diverticula in Children: A 7-Year Experience. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2015; 26 (03): 240–244. DOI: 10.1055/s-0035-1551564.

- Cruz ML da, Macedo A, Garrone G, Ottoni SL, Oliveira DE, Rosário Souza GRM do. Primary congenital bladder diverticula: Where does the ureter drain? Afr J Paediatr Surg 2015; 12 (4): 280. DOI: 10.4103/0189-6725.172574.

- Livne PM, Gonzales ET. Congenital bladder diverticula causing ureteral obstruction. Urology 1985; 25 (3): 273–276. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(85)90327-9.

- Stein RJ, Matoka DJ, Noh PH, Docimo SG. Spontaneous perforation of congenital bladder diverticulum. Urology 2005; 66 (4): 881.e5–881.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.004.

- Britto MM, Yao HHI, Campbell N. Delayed diagnosis of spontaneous rupture of a congenital bladder diverticulum as a rare cause of an acute abdomen. ANZ J Surg 2019; 89 (9): 385–387. DOI: 10.1111/ans.14559.

- Jorion JL, Michel M. Spontaneous rupture of bladder diverticula in a girl with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34 (3): 483–484. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90506-7.

- Temiz A, Akcora B, Atik E. An atypical bladder diverticulum presented with recurrent peritonitis: case report. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2011; 17 (4): 365–367. DOI: 10.5505/tjtes.2011.81542.

- Christman MS, Casale P. Robot-Assisted Bladder Diverticulectomy in the Pediatric Population. J Endourol 2012; 26 (10): 1296–1300. DOI: 10.1089/end.2012.0051.

- Nerli RB, Ghagane SC, Musale A, Deole S, Hiremath MB, Dixit NS, et al.. Congenital bladder diverticulum in a child: Surgical steps of extra-vesical excision. Urol Case Rep 2019; 22: 42–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.eucr.2018.10.009.

- Cerwinka WH, Scherz HC, Kirsch AJ. Endoscopic Treatment of Vesicoureteral Reflux with Dextranomer/Hyaluronic Acid in Children. Adv Urol 2008; 2008: 1–7. DOI: 10.1155/2008/513854.

- Aydogdu O, Burgu B, Soygur T. Predictors of Surgical Outcome in Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux Associated With Paraureteral Diverticula. Urology 2010; 76 (1): 209–214. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.11.052.

Última actualización: 2024-02-04 11:58