33: Reoperative Hypospadias

This chapter will take approximately 15 minutes to read.

Introduction

Secondary hypospadias is a term reserved for individuals with persistent anatomical and functional complications following multiple corrective hypospadias repairs. These include stricture formation, urethrocutaneous fistula, glans dehiscence, urethral dehiscence, persistent chordee and glans deformity. Hypospadias is defined by three main characteristics: a ventrally sited meatus, varying degree of chordee, and a 'hooded’ appearance of the foreskin due to the excess dorsal preputial skin, with each component exhibiting a broad spectrum of severity. Hence, in patients who present for a redo surgery following a primary repair, it is vital to recognize the combination of individual components which has failed to maximize the outcome in a redo surgery. There is also a higher rate of recurrent fistulation and strictures due to reduced tissue vascularity.

Another critical aspect to bear in mind is that the population of patients who require a secondary repair tend to be older, with studies highlighting a significant degree of psychological comorbidity and neurodevelopmental disorders.1,2 The majority of hypospadias ‘cripples’ would have had on average more than three failed attempts at urethroplasty, and failure tends to follow many years after achieving an initial satisfactory outcome.3 Anthony Mundy described the magnitude of this challenge in managing these cohorts of patients in his editorial review. He emphasised that it is almost impossible to write a good journal article on failed hypospadias repair.4 In recognizing the complications following a primary hypospadias repair, one cannot adopt a ‘one size fits all approach’ but requires an individually tailored approach. This chapter outlines the incidence and the predisposing factors and proposes a general management algorithm for children who need redo hypospadias surgery. In addition, the surgical technique preferably used in our institution will be described. This chapter will also review alternative strategies for each of the common individual complications that subsequently leads to the need for a redo procedure.

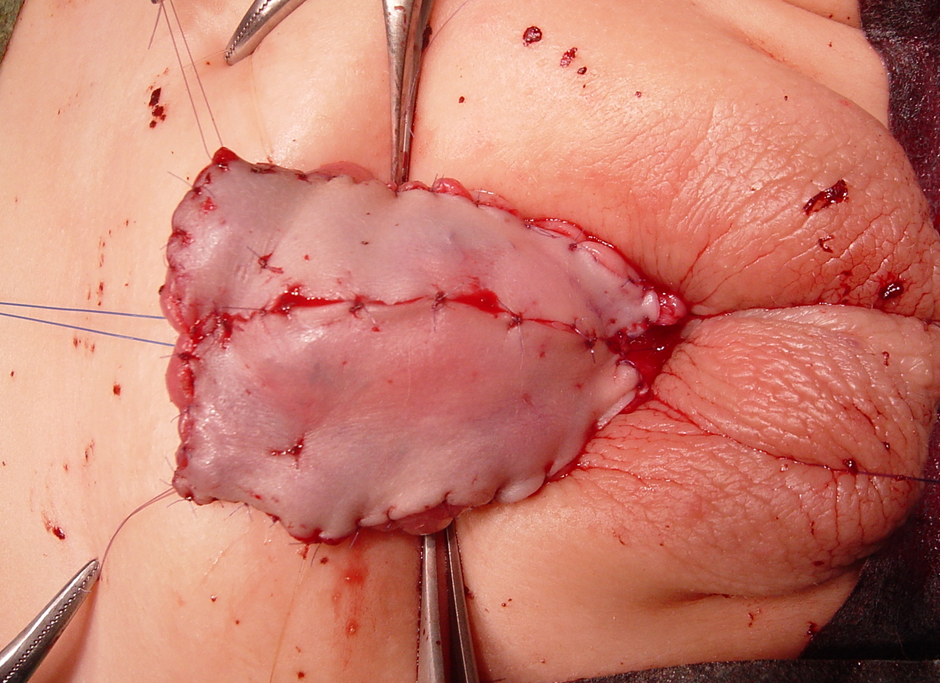

Figure 1 Preputial skin graft with quilting sutures in a 1st stage hypospadias repair. Note the glan penis, which has been split and laid wide open.

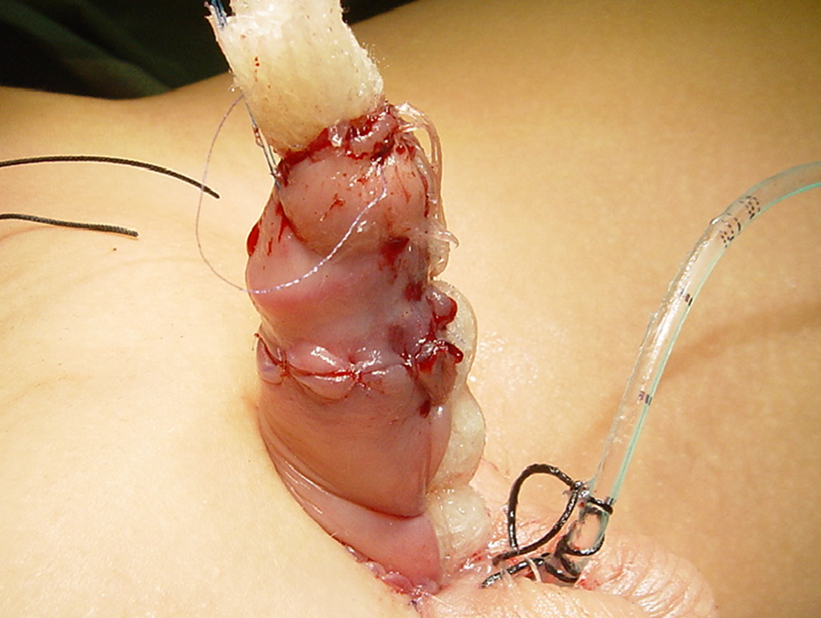

Figure 2 Rolled jelonet secured to provide moisture and immobilize the skin graft.

Incidence

Redo surgeries are primarily dependent on two critical factors: the institution’s case volume and the technical experience of the operating surgeon. Therefore, this incidence varies widely among centres. Barbagli et al reported in their retrospective analysis of a single cohort of adolescents that 50% of the patients with penile stricture had a history of a failed hypospadias repair. Of the cohort, 16.4% had undergone surgery for primary distal hypospadias, and most had more than one operation to repair the primary defect. Demographically, 21.2% of patients were 1 to 16 years old, and 38.4% were 17 to 20 years old.5 These findings highlighted the need for a long-term follow-up and emphasised the need for an effective transition of care.

Risk Factors

Urethroplasty complications increases two-fold in people undergoing a second hypospadias urethroplasty compared with those repaired primarily. These risks increase to 40% with three or more further re-operations.6 The aetiopathology of failed hypospadias repair is multifactorial. Postoperative infection, urine extravasation, residual scar tissues, haematoma, and poor surgical techniques contribute to the graft's impaired tissue healing and ischemia. The scarred ventral tissues combined with the lack of surrounding tissue in secondarily repaired hypospadias predispose patients to a poor outcome.7 Theoretically, the mismatch between the growth of the reconstructed neourethra and the growth spurt of the surrounding cavernosal tissue during the onset of puberty can potentially result in a short narrow tube and manifest as a stricture. In the paediatric population, it is recognized that older age at repair is associated with a higher risk of complications.8 Our opinion is that an experienced hypospadias surgeon should undertake a secondary repair in a high-volume centre. There is evidence that the surgical volume correlates positively with patient outcomes, especially in these group of patients.9

Diagnosis

The clinical evaluation of patients does not differ widely from those who present primarily with hypospadias. Operative details of previous operations are imperative if the patients present from a different centre. When contemplating repair, one should document the meatal location, glans volume, penile length, recurrent chordee (if any), depth, and width of the urethral plate. Other equally critical considerations are the extent of the scarred tissue and the availability of sites for donor graft, should a two-stage approach be undertaken. A thorough physical examination is mandatory and documented in full detail, with additional radiological assessment rarely necessary. The patient characteristics and a surgeon's technical preference and experience will play a role in influencing the type of repair. Lastly, the potential risks and benefits of the secondary repair should be discussed together with the parents as a shared decision-making process.

Perioperative Planning

Embarking on a redo surgery for hypospadias is technically challenging and associated with higher complication rates. The functional outcome will always be the priority over cosmesis, which should be communicated clearly. The "normal" meatal location is widely considered the glans' distal tip. However, significant variation of meatal location has been reported to preserve sexual and voiding function throughout adulthood in men with untreated hypospadias.10 Apart from just the meatal site, a survey found that men with untreated "milder" or distal hypospadias report difficulties with sexual intercourse, mostly associated with the penile curvature but with no significant urinary issues compared to normal men.10 Considering the survey result and when applied to the context of secondary repairs, chordee correction would be the prime consideration. If a two-stage surgical approach is contemplated, a minimum of 6-month interval is recommended between procedures to allow proper wound healing. Adjuncts to support tissue healing in redo hypospadias repairs have been reported in the literature, especially nitroglycerin injections and hyperbaric oxygen therapy to increase tissue vascularity and promote wound healing.11 However, these supportive treatment therapies are yet to gain wide acceptance. In children with a small penile glans’ and a short phallus, there is a continuing debate within the fraternity over the use of preoperative androgen stimulation. Some quarters advocate its use in severe hypospadias to increase phallus length, glans circumference, penile vascularity, and tissue robustness which are essential in any redo repair. However, conflicting evidence suggests that a preoperative hormonal stimulation is associated with increased complication rates in proximal hypospadias, though statistically not significant.12

Antibiotics

We would advocate antibiotic cover in a redo hypospadias to minimize the risk of the surgical site and urinary tract infections. A preoperative urine culture should be taken, and the presence of bacteriuria to be treated based on the culture and sensitivity. Despite studies finding no significant difference in the surgical site and urinary tract infections with or without preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis,13,14 we use co-amoxiclav (amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 30 mg/kg) intravenously as our first-choice antibiotic. It is then continued orally in the post-operative period for one week until the catheter and dressing is removed. Our practice is generally aligned with the study that reported 91% of paediatric urologists prescribe postoperative antibiotics when a urethral catheter is left in place.15 Even though debatable, a recent meta-analysis assessing the effects of postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis after hypospadias repair found limited utility in preventing infections and wound healing complications, although the risk of bias was high in many of the studies.16,17 Supporting patients’ recovery with adequate analgesia is essential for as they would usually require a more extensive tissue dissection with a more complex reconstruction. A caudal block would be the most common choice for perioperative pain control. Alternatively, peripheral nerve blocks (dorsal nerve penile and pudendal nerve blocks) can also be utilised. Evidence remains inconclusive regarding the choice of analgesia and its relation to postoperative outcome in hypospadias repairs.18,19

Figure 3 Appearance of the skin graft one week following surgery. The family carer needs to continue massaging the graft with vaseline or cocoa butter ointment to optimize healing and prevent graft contracture.

Figure 4 Appearance of skin graft 6 months following 1st stage repair. Good healing with no evidence of graft contracture. It is ready for the 2nd stage of the repair.

Surgical Techniques

Different approaches for salvage techniques have been reported in redo hypospadias, including tubularised incised plate (TIP) urethroplasty, the Mathieu repair, onlay tubularised island flaps (OIF), and free grafts, done in either as a single-stage or a two-stage approach. Regardless of the different techniques, one should always apply the general principles of surgery and repair. Minimal use of cautery, tension-free sutures, well-vascularised grafts or surrounding tissue, and multiple layers with watertight closure will minimise the usual potential complications. A TIP urethroplasty can be an option in a single-stage repair setting if the urethral plate is present and wide enough. Snodgrass and Lorenzo reported their initial experience of using TIP urethroplasty in redo hypospadias repair. They had 15 patients with a mean follow-up of 5 months. They achieved a cosmetically normal meatus in 13 of 15 patients, and complications comprised two fistulae and one glans dehiscence.6 Shanberg and colleagues reported TIP urethroplasty in 13 redo cases with a mean follow-up of 22 months. Cosmetic results were excellent, with two complications: one patient with glans dehiscence and a urethrocutaneous fistula, and a second patient who developed meatal stenosis.20 A grossly scarred urethral plate contributing to chordee should be excised and replaced with a buccal mucosa graft for a two-stage repair as advocated by Bracka.21

Bracka popularized the two-stage repair in hypospadias surgery as a potential solution to the high complication rates observed following a single-stage approach. He reported the most extensive series in the literature with six hundred cases (457 children and 143 adults), of which 34.8% were secondary repairs. In total, 3.7% required revision of the first stage. The urethrocutaneous fistula rate was 10.5% for salvage surgery, while the stricture formation rate was 7%.22 Hayes et al reported using buccal grafts in multistage repairs in 25 patients (both adults and children) with previously failed hypospadias repair. 22% required 1st stage revision, while only one patient (4%) developed a urethrocutaneous fistula.23 Barbagli et al studied 60 adults with secondary hypospadias, of whom 31 cases underwent multistage repairs. Buccal grafts resulted in 82% success in one-stage procedures and 82% in multistage procedures. The fistula rate for one-stage and two-stage operations was 10.3% and 6.5%, respectively.5 Kulkarni et al highlighted the higher incidence of buccal graft contracture in their series of patients undergoing a 2-stage repair with BMGs (Buccal mucosa graft), which prompted their change in technique to a hybrid approach.24

At Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children (GOSH), our two-stage repair combines techniques historically described by Turner-Warwick, Duplay, and Cloutier.25 At the first-stage repair, the scarred urethra is opened ventrally in the midline back to healthy bleeding tissue. A circumcision incision is completed around the corona of the penis, often coinciding with the previous incision and leaving a cuff of mucosa proximal to the glans. The scarred area within the glans is then excised, and the glans is opened, laid open by a deep incision in the midline, and then lifting the glanular tissue off the apex. The urethra is extended to a healthy area with good calibre tissue before excision of distal neo-urethra and scar tissue. The failed neourethra is excised partially or entirely back to the healthy tissue. Chordee is identified by an artificial erection, using a tourniquet and saline injection, and is corrected by a combination of the ventral release of the scarred neo-urethra and additional dorsal tunica albuginea plications where indicated. A wide proximal urethral opening needs to be fashioned, and the shaft skin reapplied to the dorsum of the penis. This leaves a variable raw area on the ventral surface from the urethral opening to the tip of the glans distally and between the skin edges. If an excess of healthy preputial skin is available, we use this in preference to other grafts. It is however, usually necessary, to take alternatively sited grafts. These are commonly the posterior auricular skin (Wolfe) graft, inner cheek buccal mucosal graft, and composite grafts (buccal mucosal graft plus inner prepuce). The skin graft of choice is harvested and then de-fat before applying to the raw area on the ventral surface of the penis. The grafts are usually rectangular (at least 2 cm wide), sutured circumferentially with 6/0 monocryl, and we attach it onto the penile corpora with additional quilting sutures. Grafts are compressed onto the shaft of the penis using a rolled jelonet (paraffin gauze) and sutured in place by joining the shaft skin edges together over the top. We then cover the penis and apply additional pressure using a foam and an outer wrap of Elastoplast tape. A dripping stent or continuously draining catheter is used according to the patient's age (all patients under six years of age will have a dripping stent).

Antibiotics and anticholinergics will be given for the first week The dressing is removed and graft is inspected under general anaesthetic. The parents are instructed to apply chloramphenicol ointment to the graft twice daily for ten days. After three months review in the outpatients’clinic, the second-stage procedure is planned if the graft is satisfactory. If not, a period of dihydrotestosterone ointment application will be used to further mature the graft and stimulate penile growth. Second-stage procedures are performed no earlier than six months, and most cases are repaired nearer to 1 year. The urethral strip and glans are closed around an 8-Fr catheter, using 6-0 monocryl sutures. A further foam dressing is applied with catheter drainage, antibiotics, and anticholinergics for one week. This is followed by dressing removal by our nursing staff on the ward (without any sedation). Patients are followed up at 3 and 12 months in the outpatients’ clinic.

Urethrocutaneous Fistula

Urethrocutaneous fistula is one of the most common complications of post-primary hypospadias repair, with the incidence quoted between 5% to 15%. Recognised risks include the age of repair, haematoma, graft necrosis, urinary extravasation, wound infection, and the operating surgeon’s experience. A multicentre retrospective review of 591 patients by Duarsa et al concluded that suprapubic drainage reduces the risk of urethrocutaneous fistula following hypospadias repair. The authors postulated that creating a temporary urinary diversion percutaneously reduces urinary drainage to the neourethra and minimises tissue reaction, stitch mobility, and risk of infection.10 It is also vital to exclude distal neo-meatal stenosis or ischemia of the ventral skin. The surgical management will depend on the size of the meatus, the number of fistulas, and if there are any concomitant neo-urethra strictures. Kulkarni et al have described their fistula repair techniques, whereby in cases of narrow meatus with a urethral stricture, the urethra is incised ventrally till a good calibre urethra is seen. If the urethral plate is more than 8 mm, then an Asopa single-stage dorsal inlay graft augmentation urethroplasty is performed. If the width is less than 8 mm, then a two-stage approach is employed to tubularise a neourethra. Finally, if the urethra is of a good calibre without distal obstruction, the urethrocutaneous fistula can be closed primarily.24

Recurrent Ventral Chordee

Ventral chordee (VC) is observed more frequently in patients who have undergone a dorsal plication in contrast to a ventral penile lengthening procedure. Another contributing factor is the contracture of the scarred ventral skin and peri-urethral fibrous tissue. Flynn et al reported the late onset of recurrent penile chordee post hypospadias repair after puberty. Most of their patients reported that the penile curvature was associated with the growth of the phallus at puberty. They postulated that recurrent VC, especially in adolescents, is due to the corporal wall asymmetry, which may be secondary to disproportionate growth of the hypoplastic ventral corporal wall or the reconstructed urethra.26 A mismatch between a short ventral urethra and corporal tissues is crucial in recurrent ventral chordee.27 In the majority, a ‘mild’ (less than 30 degrees) chordee can be corrected by skin dissection or transecting the urethral plate. The majority in redo hypospadias will need an underlying corporal disproportion addressed with essentially two possible options: to make the long side short or to make the short side long. Among hypospadias patients where length is precious, it is probably best to avoid dorsal plication. Transverse ventral corporotomies are preferred in recurrent chordees, leading to a reasonable degree of correction. In cases of curvature more than 30 degrees, a staged repair starting with excision of the urethra and placement of a dermal graft to the corpora and coverage with dartos flap and local skin flap is an option that can be considered.24

Figure 5 Final appearance following tubularization at the end of the 2nd stage repair. The catheter will be left for seven days, followed by a dressing removal in the ward.

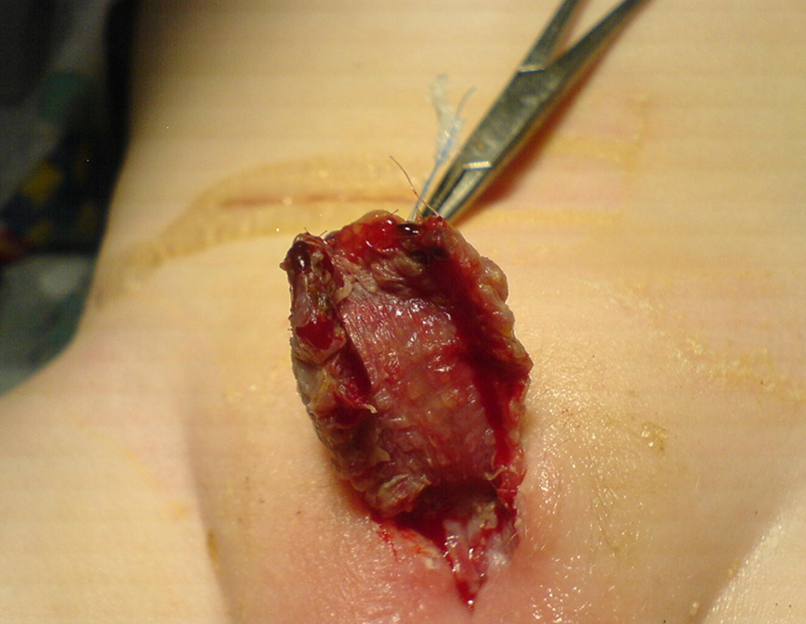

Figure 6 Presence of an isolated urethrocutaneous fistula following hypospadias repair. It is amenable to a simple fistula excision and closure

Postoperative Care

Secondary hypospadias repair at GOSH is performed as a one-day admission inpatient procedure with the child discharged the following day following an overnight observation. We catheterise all boys with a soft 8-French feeding tube and secure it to the glans with a 4-0 prolene stay suture, which stays in place for seven days. Occlusive wrapped around dressing optimises postoperative healing by promoting immobilization, surgical site protection, tissue adherence, and compression. Currently, there is no consensus on the most effective dressing type or whether applying a dressing is beneficial at all. A randomized trial found no significant difference in complication rates or clinical outcomes when patients with a dressing and without one were compared. Of note, there were significantly increased postoperative calls by parents in the non-dressing group.28 Following the dressing technique as described before, we place double nappies in children who are not yet toilet trained. The catheter and dressing are removed after seven days, under general anaesthesia for the first-stage repairs with graft and locally on the ward following the second stage repairs. A Foley catheter is connected to a drainage bag in older children. We prescribe oral antibiotics per our local microbiology policy and oxybutynin 0.2 g/kg once daily until the catheter is removed to prevent bladder spasms. The preoperative caudal nerve block helps ameliorate postoperative pain.29 Further pain control is achieved with low doses of NSAID (non-steroid antiinflammatory drugs) analgesics.

Conclusion

Redo hypospadias is a surgically challenging entity to treat and manage among surgeons actively caring for children with hypospadias. Due to its low complication rate and reproducible techniques, the authors advocate a two-stage repair for a redo hypospadias surgery. Nevertheless, if all fails despite the best of attempts, perineal urethrostomy can also be considered an option to preserve the quality of life in these patients. There is limited high-quality evidence in the current literature examining the various aspects of the surgical management of redo hypospadias. Therefore, more effort into further research to improve patient outcomes should be encouraged. An outline of a simple algorithm for the surgical management of redo hypospadias is outlined below.

Figure 7 Proposed management algorithm for reoperative or redo hypospadias.

Resources for Family

- Hypospadias Resources, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia

- Urology Information for parents and visitors, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children

Suggested Readings

- Shukla AR, Patel RP, Canning DA. Hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol: 103–126. DOI: 10.1385/1-59259-421-2:103.

- Chapter 15: Hypospadia Paediatric Urology WebBook, European Society of Paediatric Urology. 20AD: 227–256.

References

- Butwicka A, Lichenstein P, Landen M. Hypospadias and increased risk for neurodevelopmental disorders. Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015; 56 (2): 155–161.

- Jin TT, Wu WZ, Shen ML. Hypospadias and Increased Risk for Psychiatric Symptoms in Both Childhood and Adolescence: A Literature Review. Front Psychiatry 2022; 13: 799335. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.799335.

- Craig W JR, C B, WO H, JM M, J.B.. Management of adults with prior failed hypospadias surgery. 2014; 3 (2): 196–204.

- Mundy AR. Failed hypospadias repair presenting in adults. Eur Urol 2006 (5): 774–776.

- Barbagli G, Perovic S, Djinovic R, Sansalone S, Lazzeri M. Retrospective descriptive analysis of 1,176 patients with failed hypospadias repair. J Urol 2010 (1): 207–211. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(10)79536-1.

- Snodgrass WT. A Lorenzo Tubularized incised plate for hypospadias reoperation. BJU Int 2002; 89: 98–100. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000125018.90605.a5.

- Al-Sayyad A, Pike JG, Leonard MP. Redo hypospadias repair: experience at a tertiary care children’s hospital. Can Urol Assoc J 2007; 1 (1). DOI: 10.5489/cuaj.39.

- Duarsa GWK, Tirtayasa PMW. Risk factors for urethrocutaneous fistula following hypospadias repair surgery in Indonesia. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (3): 317.e1–317. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.04.011.

- Wilkinson DJ, Green PA, Beglinger S. Hypospadias surgery in England: Higher volume centres have lower complication rates. J Pediatr Urol 2017; 13 (5): 481.e1–481.e6.

- Fichtner J, Filipas D, Mottrie AM, Voges GE, Hohenfellner R. Analysis of Meatal Location in 500 Men: Wide Variation Questions Need for Meatal Advancement in All Pediatric Anterior Hypospadias Cases. J Urol 1995; 154 (2): 833–834. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)67177-5.

- Dodds PR, Batter SJ, Shield DE, Serels SR, Garafalo FA, Maloney PK. Adaptation of Adults to Uncorrected Hypospadias. Urology 2008; 71 (4): 682–685. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.07.078.

- Chang C, White C, Katz A, Hanna MK. Management of ischemic tissues and skin flaps in Re-Operative and complex hypospadias repair using vasodilators and hyperbaric oxygen. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (5): 672.e1–672.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.07.034.

- Wright I, Cole E, Farrokhyar F, Pemberton J, Lorenzo AJ, Braga LH. Effect of Preoperative Hormonal Stimulation on Postoperative Complication Rates After Proximal Hypospadias Repair: A Systematic Review. J Urol 2013; 190 (2): 652–660. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.3234.

- Smith J, Patel A, Zamilpa I. Commentary to ‘Is parenteral antibiotic prophylaxis associated with fewer infectious complications stented, distal hypospadias repair?’ J Pediatr Urol 2017; 18 (6): 764. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.05.024.

- Baillargeon E, Duan K, Brzezinski A, Jednak R, El-Sherbiny M. The role of preoperative prophylactic antibiotics in hypospadias repair. Can Urol Assoc J 2014; 8 (7-8): 236. DOI: 10.5489/cuaj.1838.

- Hsieh MH, Wildenfels P, Gonzales ET. Surgical antibiotic practices among pediatric urologists in the United States. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (2): 192–197. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.05.001.

- Chua ME, Kim JK, Rivera KC. Commentary to ‘The use of postoperative prophylactic antibiotics in stented distal hypospadias repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis.’ J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (2): 149. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.024.

- Zhu C, Wei R, Tong Y, Liu J, Song Z, Zhang S. Analgesic efficacy and impact of caudal block on surgical complications of hypospadias repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2019; 44 (2): 259–267. DOI: 10.1136/rapm-2018-000022.

- Tanseco PP, Randhawa H, Chua ME, Blankstein U, Kim JK, McGrath M, et al.. Postoperative complications of hypospadias repair in patients receiving caudal block vs. non-caudal anesthesia: A meta-analysis. Can Urol Assoc J 2019; 13 (8): 249–257. DOI: 10.5489/cuaj.5688.

- Retik AB, Borer JG. Primary and Reoperative Hypospadias Repair With the Snodgrass Technique. J Urol 1998; 16 (3): 1561. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199910000-00122.

- Bracka A. Hypospadias repair: the two-stage alternative. Br J. Br J Urol 1995; 76: 31–41. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07819.x.

- Bracka A. The role of two-stage repair in modern hypospadiology. Indian J Urol 2008; 24 (2): 210–218.

- Hayes MC, Malone PS. The use of a dorsal buccal mucosal graft with urethral plate incision (Snodgrass) for hypospadias salvage. BJU Int 1999; 83 (4): 508–509. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.00043.x.

- Kulkarni S, Joglekar O, Alkandari M, Joshi P. Redo hypospadias surgery: current and novel techniques. Res Rep Urol 2018; Volume 10: 117–126. DOI: 10.2147/rru.s142989.

- S JN, T N, K OM, M CP. The two-stage repair for severe primary hypospadias. Eur Urol 2006; 50 (2): 366–371.

- Flynn JT, Johnston SR, Blandy JP. Late Sequelae of Hypospadias Repair. Br J Urol 1980; 52 (6): 555–559. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1980.tb03114.x.

- Abosena W, Talab SS. Moneer K Hanna Recurrent chordee in 59 adolescents and young adults following childhood hypospadias repair. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 162 (e1-162.e5). DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.11.013.

- Van Savage JG, Palanca LG, Slaughenhoupt BL. A Prospective Randomized Trial Of Dressings Versus No Dressings For Hypospadias Repair. J Urol 2000: 981–983. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00015.

- O’Kelly F, Pokarowski M, DeCotiis KN, McDonnell C, Milford K, Koyle MA. Structured opioid-free protocol following outpatient hypospadias repair - A prospective SQUIRE 2.0-compliant quality improvement initiative. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (5): 647.e1–647.e9. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.06.012.

- Shukla AR, Patel RP, Canning DA. Hypospadias. J Pediatr Urol: 103–126. DOI: 10.1385/1-59259-421-2:103.

- Chapter 15: Hypospadia Paediatric Urology WebBook, European Society of Paediatric Urology. 20AD: 227–256.

Last updated: 2023-02-23 00:12