4: Pediatric Urodynamic Assessment

This chapter will take approximately 20 minutes to read.

Introduction

The urodynamic assessment of the lower urinary tract (LUT) function comprises the use of appropriate methods of evaluation during the bladder filling and voiding phases. The correct instrumentation of the studies provides the pathophysiological understanding of urologic entities that may affect children and adolescents with the aim of optimizing their therapeutic management.

Pediatric urodynamics requires trained staff that must implement an appropriate methodology in a setting adapted to the pediatric universe in order to deal with situations of stress correctly and obtain as much clinical urologic information as possible.

The urodynamic study of LUT can be performed in an invasive or a non-invasive fashion. In general, the current trend consists in managing LUT entities with non-invasive urodynamic evaluation and using invasive methods only in the case of neuro-urological dysfunction or complex urologic malformations.

Non-Invasive Urodynamic Evaluation

LUT conditions in children encompass a group of entities with overlapping urinary symptoms. These conditions are the result of disorders in the filling phase, the voiding phase, or a combination of both with different degrees of compromise. LUT symptoms can be observed in up to 20% of school children.1

The correct evaluation is determined by the pediatrician, and other specialists continue with this assessment. This approach is started when the child is around 4 years of age, and it will be more substantial if the following data can be obtained:

- Voiding diary (2-3 days).2

- Bristol scale / Rome IV criteria / Functional gastrointestinal disorders.3,4

- Questionnaires (optional): urine and bowel evacuation habits, fluid intake, quality of life.5

- Physical examination of the genital, lumbo-sacral area, gluteal region, perineum, lower limbs, reflexes.

- Urinalysis / Urine culture: proteinuria / glycosuria.

- Uroflowmetry / Post-void residual (PVR) urine measurement.

- Pelvic floor electromyography (EMG) with surface (patch) electrodes

- Ultrasonography of the upper urinary tract, bladder characteristics, constipation signs.

- Urodynamic / video urodynamic studies (not required unless patients are refractory to initial treatment).

- Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) to detect vesicoureteral reflux

There exist a variety of questionnaires for the evaluation and measurement of bladder and bowel dysfunction, quality of life and behavioral comorbidities that include indications and possible difficulties. The most useful tool will be chosen by the physician considering the clinical assessment, the time available and the patient population under study.5

Functional gastrointestinal disorders in children occur in different ways and may be present in children at the age of 3 or 4 years old and be later associated to bladder dysfunction and urinary infections.6,7

Uroflowmetry

Uroflowmetry (with post-void residual measurement) can be combined with pelvic floor electromyography (EMG) to confirm dysfunctional voiding with lack of coordination between detrusor and urinary sphincter. Urodynamic studies are reserved for patients who are refractory to initial treatment.8,9

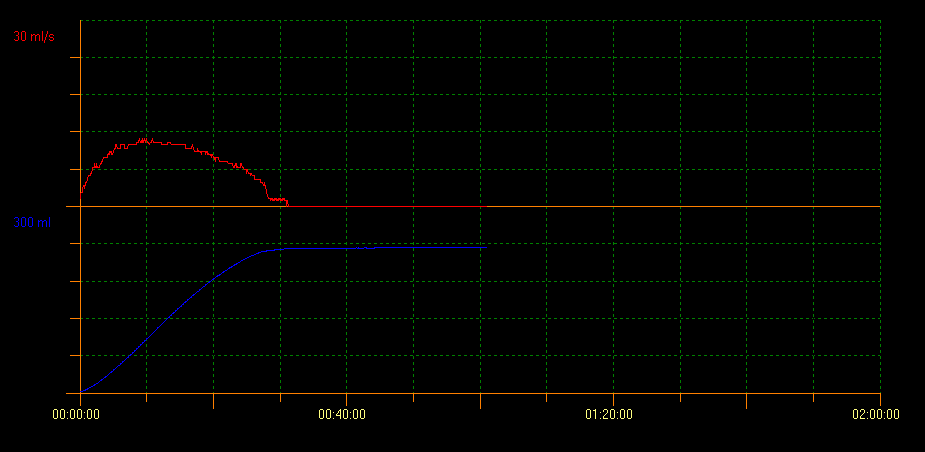

Uroflowmetry is a non-invasive procedure used to measure urine flow and it is defined as the volume of urine that passes through the urethra in a unit of time expressed in mL/sec. The variables assessed are maximum flow rate (Qmax), average flow rate (Qavg), total voided volume and total voiding time. This method also shows morphology of the curve obtained during voiding. A normal flow shows as a bell-shaped curve (Figure 1). It is one of the initial studies used to evaluate bladder voiding, since it provides information on detrusor contractility and bladder outlet. With this technique it is possible to avoid invasive tests and to monitor therapeutic responses.

Figure 1 Normal flow showing bell-shaped curve

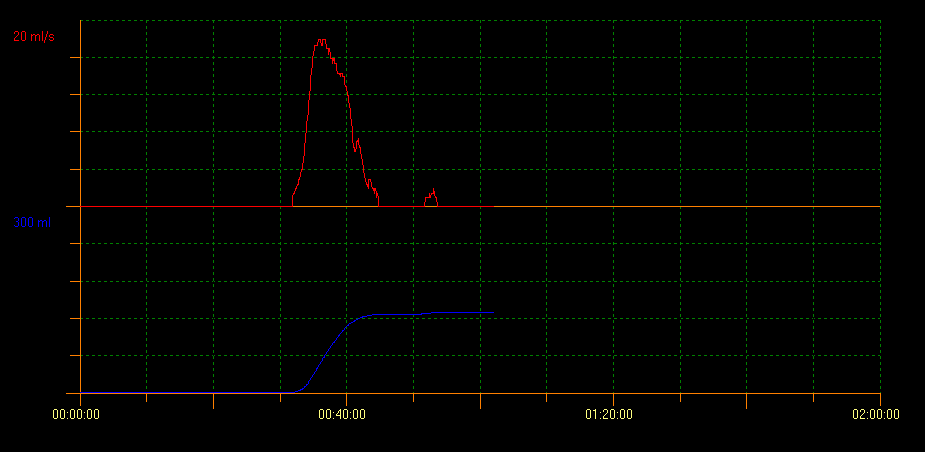

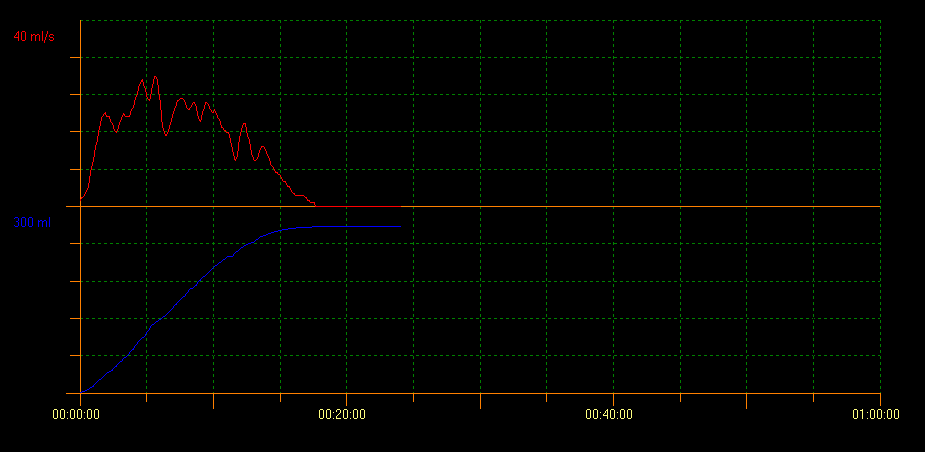

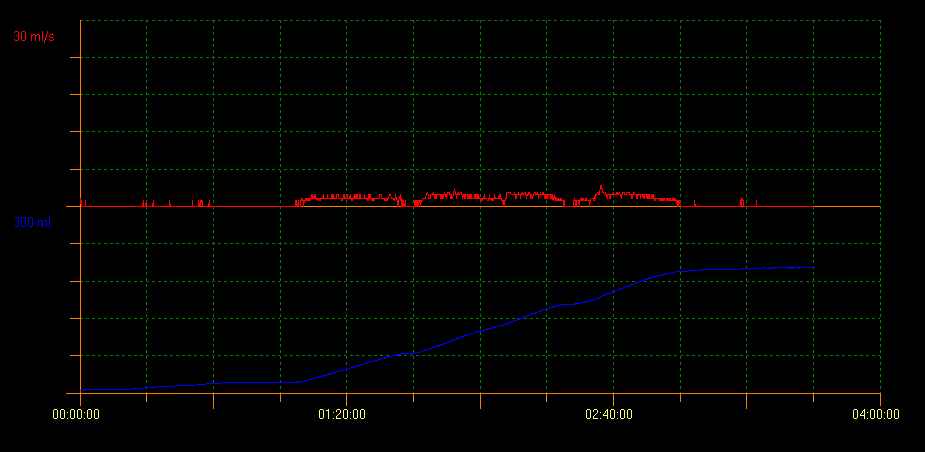

Uroflow measurement of PVR with ultrasound scan evaluates bladder voiding capacity. With this method several curve patterns that indicate different conditions can be identified. A tower curve pattern is indicative of an overactive bladder; a staccato curve pattern shows dysfunctional voiding, and an interruptive flow pattern can be suggestive of an underactive bladder. A plateau curve pattern is generally observed in patients with anatomical bladder obstruction (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4).10

Figure 2 Tower curve pattern

Figure 3 Staccato curve pattern

Figure 4 Plateau shaped curve pattern

There is a considerable variety of inter-observer results, especially in the case of abnormal uroflow tests, and this is one of the main limitations of this tool. Franco et al developed the concept of flow index (FI). FI was created as a measure of the actual flow rate in relation to the expected flow rate: AQavg/EQavg or AQmax/EQmax) to obtain a quantitative evaluation of bladder evacuation. Thus, the FI can help predict the estimated flow rate in a reliable way given a specific urine volume within reasonable parameters; it helps compare actual flow rates with ideal ones and, therefore, it provides more objectivity to the analysis of curves.11 A higher FI is indicative of efficient voiding and a tower curve pattern, whereas a lower FI shows dysfunctional voiding and a plateau curve pattern.

Uroflowmetry and Pelvic Floor Emg

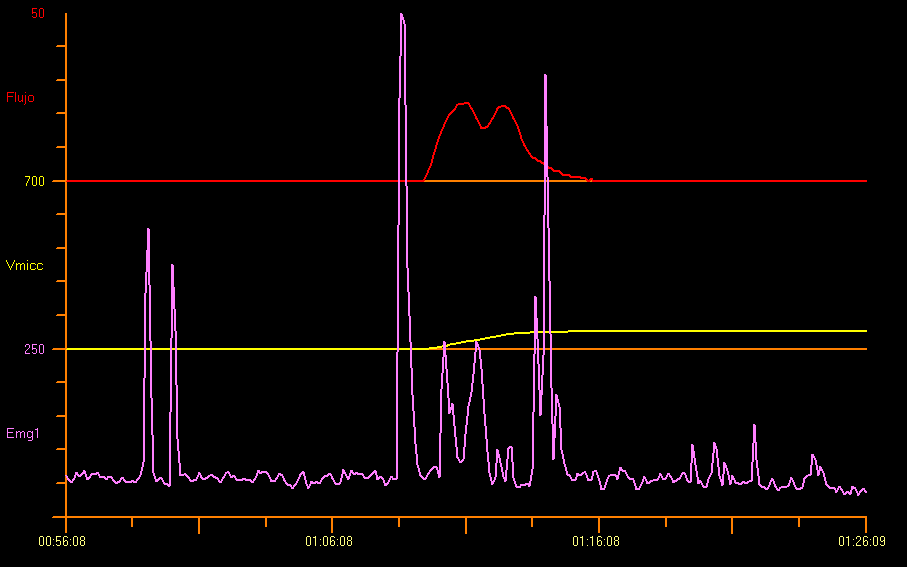

Even though staccato uroflow is the most common pattern observed in children with a diagnosis of voiding dysfunction as evidenced on positive uroflow/EMG during voiding, almost one third of the pediatric population show interruptive or mixed uroflow pattern in voiding dysfunction. Therefore, it is important to incorporate surface EMG electrodes in the uroflow study, especially when there is a suspicion of voiding dysfunction due to detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia.12 Uroflowmetry plus pelvic floor EMG is not only useful to diagnose specific LUT conditions, but also to objectively monitor the efficacy of treatment.13 This is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Flowmetry and Perineal Electromyography (EMG)

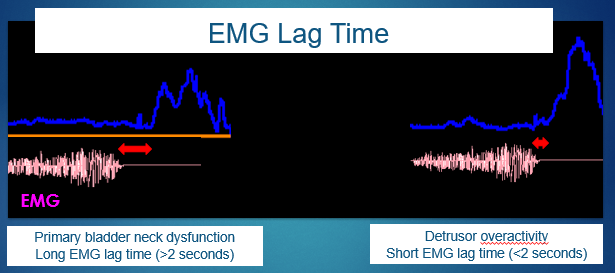

Pelvic floor EMG lag time is defined as the interval between the start of pelvic floor relaxation and the start of the urine flow curve. This non-invasive measurement in seconds is not useful to screen for conditions such as primary bladder neck dysfunction, among others.13,14 See Figure 6 for a graphic explanation of lag time.

Figure 6 Electromyography (EMG) lag time.

Nevertheless, even when considering the limitations of the use of EMG with surface electrodes, it is possible to correlate FI and EMG lag time to define the specific diagnosis of LUT conditions. A lag time close to 0 seconds is associated with a greater FI, which represents overactivity that is commonly observed in the tower flow pattern. However, children that present with a lag time over 6 seconds or even negative lag time values lower than 4 seconds showed a lower FI, which implies a hypo-efficient micturition and a plateau flow pattern.15

Post-Void Residual on Ultrasound Scan

Post-void residual measurements in neurologically intact children are highly variable. In children 4–6 years old a single PVR > 30 ml or > 21% of bladder capacity (BC), where BC is determined as voided volume (VV) + PVR and expressed as percent of the expected bladder capacity (EBC = [age (yrs)+1] × 30 mL), it is recommended that a repeated PVR be performed with dual measurements, and a repeated PVR > 20 mL or > 10% BC is considered significantly elevated. In children 7–12 years old, a single PVR > 20 ml or 15% BC, or repeated PVR > 10 ml or 6% BC is considered elevated. Standard conditions should be applied to measuring PVR: the bladder should not be underdistended (< 50%) nor overdistended (> 115%) in relation to the EBC, and PVR must be obtained immediately after voiding (< 5 min).16

When there is a LUT condition, an ultrasound of the upper urinary tract is indicated to rule out other anomalies, such as hydronephrosis and duplex collecting systems. The presence of alterations in the bladder wall, like thickness, trabeculation or diverticula can be markers of chronic LUT dysfunction.

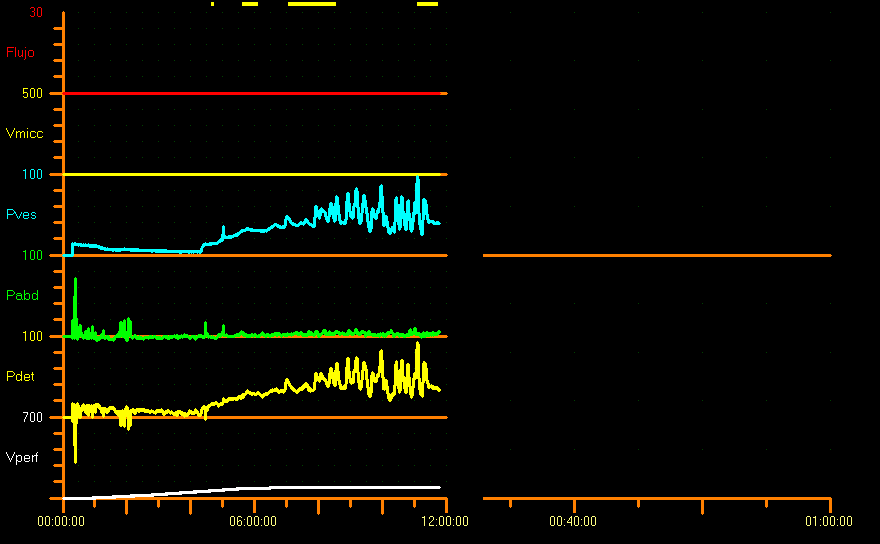

Invasive Urodynamic Evaluation—Cystometry

Urodynamic studies are not usually used to evaluate LUT symptoms in children who are neurologically intact, and they rarely provide more information that could justify its use. These studies are used when there are pathological findings on non-invasive studies, if treatments are not effective and when symptoms such as incontinence or urinary infections become aggravated.17

Nevertheless, invasive urodynamics is routinely used in initial evaluation, in the follow-up of children with neurogenic bladder due to spina bifida, when there is a suspicion of neurogenic detrusor-sphincter dysfunction (occult spinal dysraphism), obstruction (in posterior urethral valves), genitourinary anomalies (exstrophy, epispadias), non-neurogenic bladder dysfunction or significant post-void residual of unknown etiology.9

During cystometry, the intravesical pressure/volume relationship is measured to document the function of storage and voiding. In the first stage of the study, these data are obtained: detrusor stability, leak point pressures, bladder sensation and bladder capacity. In the voiding phase, other parameters are measured: voiding pressure; pressure of bladder neck opening and urinary sphincter; efficiency of detrusor contraction and sustainability; uroflow pattern, and EMG synergy. Through a rectal balloon catheter, the changes in abdominal pressure and their influence in bladder pressure are evaluated.

The standardization and nomenclature defined by the International Children's Continence Society (ICCS) Guidelines were used.9 Intravesical pressure is measured with a 6-French double-lumen catheter placed through the urethra. Intra-abdominal pressure was measured using an 8-French catheter and vinyl balloon catheter placed in the rectum. The bladder was filled with 0.9% saline at 37.5° Celsius at a rate of 5–10% of the child’s theoretical or expected bladder capacity per minute to a maximum rate of 10 mL/min.

The following urodynamic variables are evaluated: maximum cystometric capacity (MCC in mL); end filling detrusor pressure (Pdet in cm of water) and detrusor leak point pressure (DLPP in cm of water). We calculated the expected bladder capacity (EBC) following the formula: 30 × (age in years + 1) mL. Reduced bladder capacity was defined as < 65% EBC.7 We define maximum cystometric capacity when we stop filling for the following reasons: detrusor contraction with significant volume of leaks; leaks that exceed the filling rate (> 10 ml / sec); risk pressures (> 40 cm of water) high-grade vesicoureteral reflux in video urodynamic studies, and urinary tract dilation. Detrusor overactivity was defined with the presence of two more detrusor contractions greater than 15 cm of water.18 Inefficient bladder voiding is defined by detrusor underactivity or neurogenic acontractile detrusor.7

Stage Previous to Urodynamic Studies

It is important to explain in detail the procedures to parents and patients and to show them the urodynamics suit and material to use. The facility should be adapted to pediatric patients and there should be trained staff able to manage awake children. The ideal setting would include available entertainment, such as games, tablets, TV set and video games according to age. Furthermore, it is worth highlighting the importance of reaching an empty rectum, especially in the case of constipated children.

It is recommended to start the procedure with a negative urine culture collected no later than 15 days before. In children who are going to initiate clean intermittent catheterization (CIC), the urine culture may not be required, since if there is asymptomatic bacteriuria, it is not considered an extra risk factor and in general, it does not require antibiotic prophylaxis. The global incidence of urinary tract infections (UTIs) occurring post-urodynamic studies is low (0.7%). Patients without urine culture prior to undergoing urodynamics do not have a significant increase in UTIs.19

If the patient controls sphincters, is not under CIC program and has a full bladder, free uroflowmetry is performed with prior instrumentation. These data would complement the final report about that patient.

Sedation with midazolam administered via one of the three routes, oral, nasal or rectal, is a safe and efficient method and a convenient option during cystometry, especially in the group of young patients that may feel scared and stressed when faced with the procedure to be performed. Most patients are satisfied with the application of sedation as reported by Özmert. In that report, the group receiving a faster initiation of sedation and the lowest doses applied in a nasal fashion had more favorable outcomes despite having nasal stinging, in comparison with the group that received oral sedation. Another advantage of sedation was that cystometry was performed in a shorter time in sedated patients compared with the control group, and cystometry was not altered by midazolam.20 Chloral hydrate as a sedative is largely used in children in diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. The oral solution is an effective and appropriate alternative for sedation in children.21

Urodynamic Instrumentation

In general, a transurethral double-lumen 6-French catheter is inserted after applying xylocaine as an anesthetic. In some cases, as with non-collaborative children, those with comprehension difficulties or preserved urethral sensitivity, or those with a suspicion of obstructive urethra (posterior urethral valves), the collocation of a suprapubic double-lumen catheter 24 hours before the test makes it possible to better perform the study.22 It is also possible to place a double-lumen catheter in a vesicostomy or ureterostomy and then close the stoma with a silicone Foley balloon catheter.

Transurethral and rectal catheters must be secured with adhesive tape to the skin opening, and by means of connecting tubes they are attached to the external pressure transducers and leveled to the height of the pubic symphysis. Before the patient is placed in a seated position and after cleaning the skin of the perineum, two surface EMG electrodes are connected symmetrically, left and right from the perianal area, in order to record the activity of the pelvic floor muscles. In addition, a third reference electrode is placed over a bony prominence. The filling cystometry is generally performed in a sitting position; however, a supine position or the child being held in mother’s arms is also acceptable.23 See Figure 7 for an example position.

Figure 7 Position of patient

In neurologically able children and old enough to respond, the filling sensation must be determined following the standard sequence set by the ICS (International Continence Society): “first sensation of filling”, “first desire to void” and “strong desire to void”. After the micturition cycle is finished and depending on the quality of the curve, we should wonder if it is necessary to repeat the test. Once the catheters and the EMG electrodes are removed, the patients are instructed to increase the fluid intake to diminish the risk of urinary tract infection,23 and in case there is discomfort, to use of analgesic medication.

Interpretation of Urodynamic Results

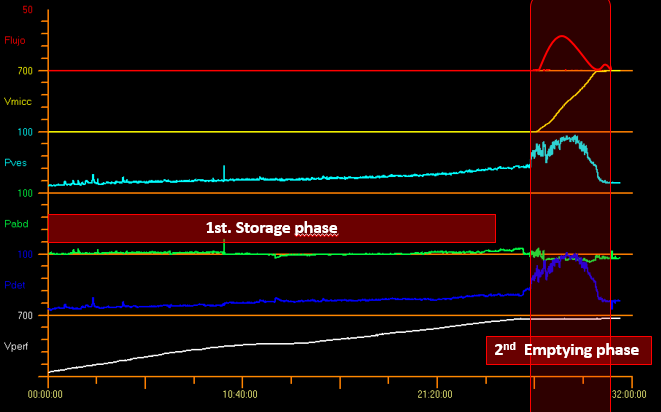

It is essential to know that a large part of the study time is consumed in the filling phase and a smaller proportion of the time in the emptying phase. Bladder cycle in Figure 8.

Figure 8 Bladder cycle.

Filling Phase

Bladder sensation may be a relevant parameter only in the case of children who are able to void willingly. As of age 4 the following data can be documented: “first desire to void” and “strong desire to void”. The child usually expresses a normal desire to urinate when they curl their toes. In addition, bladder sensation can be classified as normal, increased (hypersensitive), reduced (hyposensitive) or absent.

The parameters measured during the storage phase include: intravesical pressure (Pves), abdominal pressure (Pabd) and detrusor pressure (Pdet) where Pdet = Pves - Pabd (Figure 8).

The filling detrusor pressure (Pdet fill) is the detrusor pressure during the filling phase, and the detrusor pressure reached at the end of filling is called maximum detrusor pressure (Pdet fill max). The elasticity of the bladder wall, or wall compliance, normally increases progressively during the filling phase and can be calculated based on the initial and final points of filling rate (considering resting pressure in case of overactivity). Thus, bladder compliance is defined as the relationship between the change in bladder volume and the change in detrusor pressure (C= ΔV/ΔP; normal value: > 10 mL/cm H2O).24 The filled volume does not take into account the amount of actual diuresis produced during the test. To integrate this volume, the maximum cystometric capacity (MCC) is calculated with the voiding volume and post void residual volume. Compliance variability depends on several factors such as: section of the curve used for the calculation; bladder shape, thickness and mechanical/viscoelastic properties of the bladder wall; detrusor capacity of relaxation, contractility and degree of bladder outlet resistance.25

Furthermore, the shape of the filling curve should be considered since it provides information about bladder laxity. Normally, detrusor pressure remains relatively stable during bladder filling, which results in a linear curve. In pathological conditions, the filling curve is “nonlinear”, with an increase in detrusor pressure, and these changes should be documented.7 Generally, there is little or no change in pressure during the filling phase, when compliance is ensured, but there are no cut-off values to define pathological compliance. In children without neuropathic lesions, compliance should not exceed in 0.05 Y mL/cm H2O the baseline bladder pressure (Y= cystometric capacity [mL] by age). There is no report in the literature on the relationship between expected bladder capacity (EBC) and cystometric bladder capacity. Nevertheless, some authors suggest that Pdet should not exceed 30 cm H2O at EBC.26 In our center we consider pathological pressures from 20 cm of water to expected bladder capacity (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Compliance reduced pattern

Due to this limitation, we can extrapolate and use detrusor pressure reached at expected bladder capacity and Pdet fill max. Tarcan et al studied bladder pressures in children with myelomeningocele at 3 years of age and concluded that a DLPP cut-off value of 20 cm H2O showed a higher sensitivity in the prediction of upper urinary tract damage, whereas a DLPP between 20 and 40 cm H2O was not reliable in terms of prediction of damage. Thus, in Tarcan’s study 57.1% of children with DLPP between 20 and 40 cm H2O, and 62.2% of children with DLPP greater than 40 cm H2O had normal upper urinary tract. Therefore, DLPP cut-off value used as a single parameter to predict urinary tract damage in children with myelomeningocele is neither reliable nor accurate. Other risk factors are likely to coexist, such as low bladder capacity, low bladder wall compliance, high filling pressure, detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia, and bladder catheterization adherence, among others.27

Any phasic increase in detrusor pressure during filling cystometry is defined as detrusor overactivity. This overactivity involves the presence of two or more detrusor contractions greater than 15 cm H2O18 and may occur spontaneously or be caused by cough or Credé. This detrusor increment or hyperactivity can be neurogenic or idiopathic as in Figure 10.28,29

Figure 10 Overactive pattern

It is also likely that the child may not suppress these contractions completely and thus an increase in the pelvic floor EMG activity might be observed, as a protective reflex. Some trigger factors such as coughing, laughing, walking or jumping can generate overactivity of the detrusor. However, the presence of these contractions does not necessarily imply a neurological disorder. In the case of babies without any disease, 10% of them experience detrusor contractions. When there is detrusor contraction with little effort or without end filling (when filling reaches 150% of EBC), the detrusor muscle becomes underactive.9

Detrusor leak point pressure (DLPP) indicates the lowest detrusor pressure at which urine leakage occurs in the absence of an increase in abdominal pressure or of a detrusor contraction. Abdominal leak point pressure (ALPP) refers to the lowest value of intravesical pressure that is intentionally increased (for example, due to cough) which causes urinary leakage in the absence of a detrusor contraction. High DLPP (> 40 cm H2O) is often induced by the decrease in bladder wall laxity. Low DLPP indicates sphincter incompetence.7 Stress incontinence is present in adolescents who are physically active, when ALPP is greater than urethral pressure.30

Despite the stimuli, it is probably necessary to remove the catheter so that the child can urinate. If voiding volume is low, we are faced with detrusor underactivity due to chronic bladder outlet obstruction or a neuropathic lesion that progresses into voiding deterioration.7

Voiding Phase

Normal voiding is performed with the voluntary initiation of a detrusor contraction; it is sustained and cannot be suppressed easily once it has started. During micturition, the detrusor can be classified as normal, underactive or acontractile, i.e., it does not show any activity during voiding. If the lack of contractility has a neurologic cause it is called detrusor areflexia. It shows the complete absence of a contraction coordinated by nervous control mechanisms. When the detrusor contraction is inadequate in magnitude and duration to effectively void the bladder, we are in the presence of detrusor underactivity during voiding.9

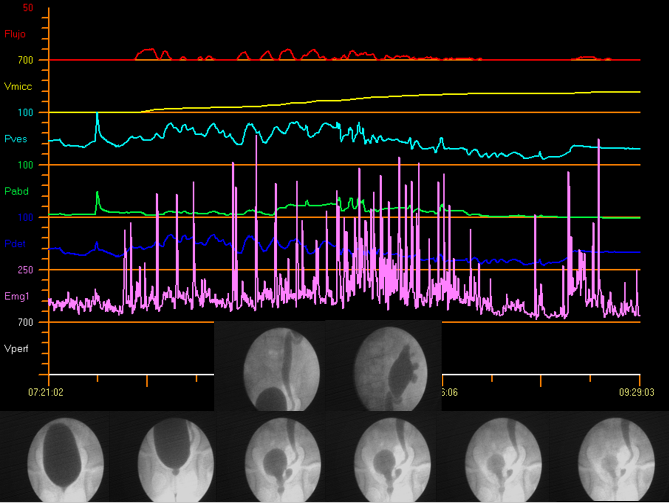

Some authors have reported pressures far higher than normal in neurologically healthy children of 1 month of age, with a mean detrusor pressure during voiding of 127 cm H2O in boys and 72 cm H2O in girls.31 Figure 11 shows an example study with bladder outlet obstruction. This is probably due to a considerable sphincter activity and catheter-related effect. In the case of children afraid of urinating there may be high voiding pressures, interrupted uroflow or considerable PVR.9

Figure 11 Infravesical obstruction

When there is anatomical urethral obstruction (posterior urethral valves, urethral stenosis, ectopic ureterocele), there is a plateau uroflow curve, with low and constant Qmax, despite the high detrusor pressure and complete relaxation of the external urethral sphincter. See Uroflowmetry section.

Functional obstruction is due to the external urethral sphincter contraction (constant or intermittent) during voiding that creates a narrow urethral segment. It is possible to document the pelvic floor activity with simultaneous pressure/flow records and pelvic floor EMG, using surface electrodes.12,15

Video Urodynamics

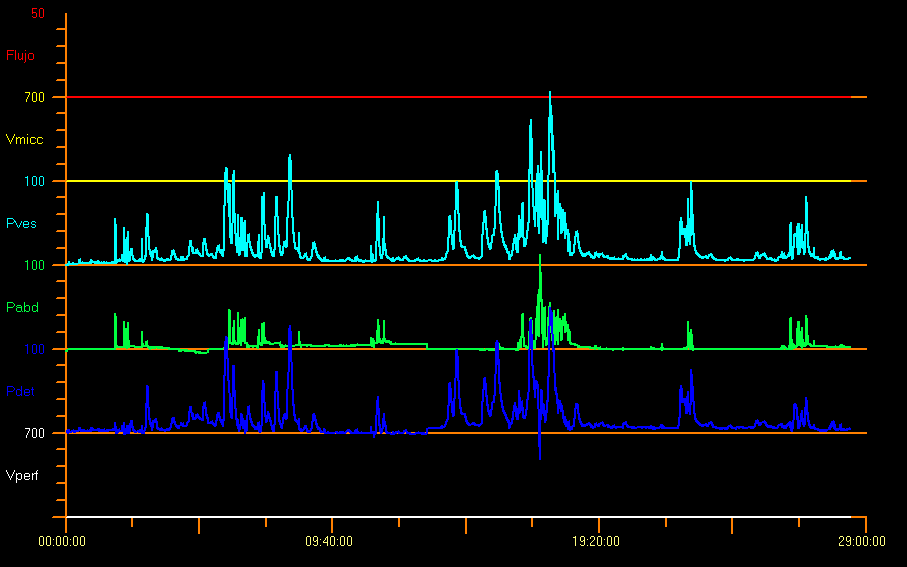

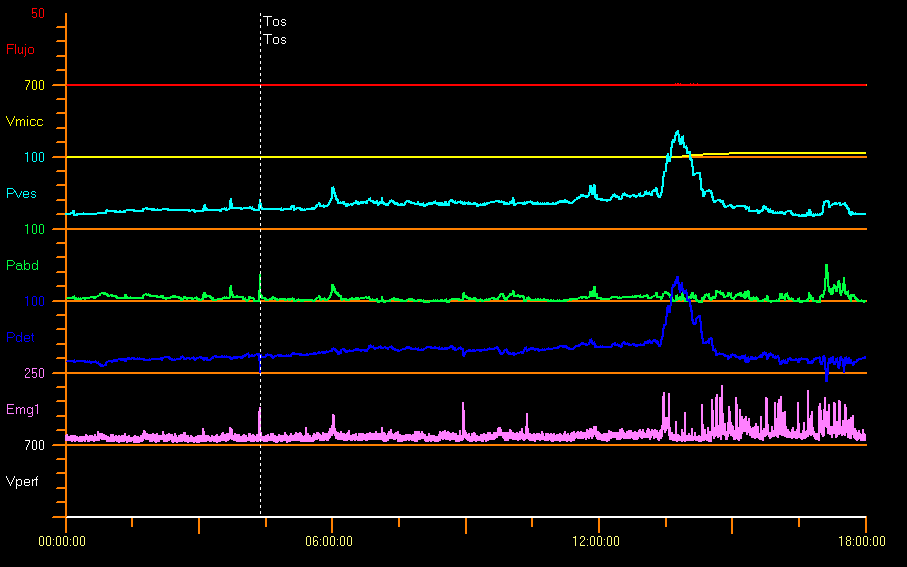

Video urodynamic studies combine the benefits of both fluoroscopic cystourethrography and conventional urodynamics in a single instrumentation, which makes it possible to carry out the simultaneous anatomical and functional assessment of the urinary tract. Figure 12 demonstrates video urodynamics.

Figure 12 Video urodynamics

Adjuvant radiology has become a useful tool in differential diagnosis. Furthermore, it facilitates the analysis of images with digital technology.32

Indications to Perform Video Urodynamic Studies

Video urodynamic studies are indicated when there is unclear diagnosis after simpler tests are performed or in the case of patients with complicated conditions such as:

- Recurrent urinary infections: suspicion of vesicoureteral reflux, and urinary symptoms such as urinary incontinence.

- Congenital malformations of the urinary tract: posterior urethral valve; Prune-Belly Syndrome.

- Multiple bladder diverticula; previous surgeries of the urinary tract.

- History of treatment in pelvic area: resection of tumors, chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

- Suspicion or history of bladder obstruction.

- Suspicion of detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia (as on EMG).32

- Spina bifida; occult spinal dysraphism.

- Cerebral palsy; Anorectal malformation and myelopathies.

- Spinal malformations; severe scoliosis; sacral agenesis.

- Other immunologic and neurologic entities.

- Pre-transplant renal evaluation and follow-up of congenital anomalies of kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT).

In our initial evaluation of patients with myelomeningocele (n:60), we could perform video urodynamic studies in all the patients within the first 8 months of life on average, and we detected 20% of children with vesicoureteral reflux, 55% with overactivity, 13% with bladder wall hypertonia, and 98% with high PVR.33

There is a cost to having the additional information provided by video urodynamics: children are exposed to radiation. The weight of the patient and bladder capacity are independent predictors of total exposure to radiation. Being aware of this exposure may help the physician to cautiously use fluoroscopy and better assess parents on the exposure to radiation.34

Unconventional Urodynamics

In 1996 De Gennaro showed that it is feasible to perform continuous urodynamic monitoring in children and that it has advantages over standard cystometry in the investigation of children with neuropathic bladder even if it is carried out for short term (6 hours).35

When there is no correlation between urinary diary volumes (in LUT conditions) or bladder catheterization diary (in neurogenic bladder) and conventional urodynamic results, there is an optional method: urodynamics with spontaneous filling. With this modality it is not necessary to use liquid filling, but the patient must remain longer in hospital, connected to the urodynamic equipment to be monitored. Even though once the patient is admitted they are required to start hydration, the duration of the study is variable and in general it ends when a leakage occurs. During bladder voiding, pressures continue being measured in an alternating way (pressure check and emptying), and then they are correlated with the volumes in a reverse way to standard urodynamics, until voiding ends.

Ambulatory Versus Conventional Urodynamics

Conventional urodynamics consists of a highly standardized evaluation. However, when evaluating children, reliability of the measurements may be influenced by the effects of development and variability of data, as well as by the unfamiliar clinical environment. Ambulatory urodynamics provides an alternative to these limitations: it requires natural filling, it is measured during a prolonged period of time, and it is carried out in a friendly environment for children.

Lu et al identified different voiding patterns in ambulatory urodynamics in comparison with standard urodynamics, with lack of consistency in the voiding pattern identified with each method.36 Perhaps also considering the last bowel evacuation, the quantity of liquid previously drunk, and the time of the day when the study is performed may explain why less consistent voiding patterns were observed in the ambulatory urodynamic studies.

Final Considerations

Most LUT entities can be assessed with non-invasive urodynamic tools and can be managed with an adequate treatment and follow-up.

For some children, invasive urodynamic studies are experienced as a stressful situation in an unfriendly environment. To counteract this scenario and profit from all the benefits of an invasive practice, it is essential to count on trained professional staff with enough patience to support the children and their families.

It is fundamental that the urodynamic team and all the other professionals involved be aware of the updated standardizations and nomenclatures of entities and of good urodynamic practices, to communicate and report results in a common language. In this way, research will provide more sound findings.

References

- Linde JM, Nijman RJM, Trzpis M, Broens PMA. Prevalence of urinary incontinence and other lower urinary tract symptoms in children in the Netherlands. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (2): 164.e1–164.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.10.027.

- Lopes I, Veiga ML, Braga AANM, Brasil CA, Hoffmann A, Barroso U. A two-day bladder diary for children: Is it enough? J Pediatr Urol 2015; 11 (6): 348.e1–348.e4. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.04.032.

- Burgers RE, Mugie SM, Chase J, Cooper CS, Gontard A von, Rittig CS, et al.. Management of Functional Constipation in Children with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol 2013; 190 (1): 29–36. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.01.001.

- Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, Hyman PE, Nurko S, Saps M, et al.. Prevalence of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Utilizing the Rome IV Criteria. J Pediatr 2018; 195: 134–139. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.12.012.

- Chase J, Bower W, Gibb S, Schaeffer A, Gontard A von. Diagnostic scores, questionnaires, quality of life, and outcome measures in pediatric continence: A review of available tools from the International Children’s Continence Society. J Pediatr Urol 2018; 14 (2): 98–107. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.12.003.

- Lee LC, Koyle MA. The Role of Bladder and Bowel Dysfunction (BBD) in Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections. Curr Bladder Dysfunct Rep 2014; 9 (3): 188–196. DOI: 10.1007/s11884-014-0240-0.

- Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, Chase J, Franco I, Hoebeke P, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2016; 35: 471–481. DOI: 10.3410/f.718270635.793500042.

- Schewe J, Brands FH, Pannek J. Voiding Dysfunction in Children: Role of Urodynamic Studies. Urol Int 2002; 69 (4): 297–301. DOI: 10.1159/000066129.

- Bauer SB, Nijman RJ, Drzewiecki BA, Sillen U. Faculty Opinions recommendation of International Children’s Continence Society standardization report on urodynamic studies of the lower urinary tract in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2015; 34 (7): 640–647. DOI: 10.3410/f.725510393.793507237.

- Tekgul S, Stein R, Bogaert G, Undre S, Nijman RJM, Quaedackers J, et al.. EAU-ESPU guidelines recommendations for daytime lower urinary tract conditions in children. Eur J Pediatr 2020; 179 (7): 1069–1077. DOI: 10.1007/s00431-020-03681-w.

- Franco I, Shei-Dei Yang S, Chang S-J, Nussenblatt B, Franco JA. A quantitative approach to the interpretation of uroflowmetry in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2016; 35 (7): 836–846. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22813.

- Wenske S, Van Batavia JP, Combs AJ, Glassberg KI. Analysis of uroflow patterns in children with dysfunctional voiding. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (2): 250–254. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.10.010.

- Van Batavia JP, Combs AJ, Fast AM, Glassberg KI. Use of non-invasive uroflowmetry with simultaneous electromyography to monitor patient response to treatment for lower urinary tract conditions. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (3): 532–537. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.11.015.

- Combs AJ, Grafstein N, Horowitz M, Glassberg KI. Primary Bladder Neck Dysfunction In Children And Adolescents I: Pelvic Floor Electromyography Lag Time–a New Noninvasive Method To Screen For And Monitor Therapeutic Response. J Urol 2005; 173 (1): 207–211. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000147269.93699.5a.

- Ha JS, Lee YS, Han SW, Kim SW. The relationship among flow index, uroflowmetry curve shape, and EMG lag time in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2020; 39 (5): 1387–1393. DOI: 10.1002/nau.24349.

- Chang S-J, Chiang I-N, Hsieh C-H, Lin C-D, Yang SS-D. Age- and gender-specific nomograms for single and dual post-void residual urine in healthy children. Neurourol Urodyn 2013; 32 (7): 1014–1018. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22342.

- Bauer SB, Austin PF, Rawashdeh YF, Jong TP de, Franco I, Siggard C, et al.. International children’s continence society’s recommendations for initial diagnostic evaluation and follow-up in congenital neuropathic bladder and bowel dysfunction in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2012; 31 (5): 610–614. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22247.

- Tanaka ST, Yerkes EB, Routh JC, Tu DD, Austin JC, Wiener JS, et al.. Urodynamic characteristics of neurogenic bladder in newborns with myelomeningocele and refinement of the definition of bladder hostility: Findings from the UMPIRE multi-center study. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (5): 726–732. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.04.019.

- Lopez Imizcoz F, Burek CM, Sager C, Vasquez Patiño M, Gomez YR, Szklarz MT, et al.. Pediatric Urodynamic Study Without a Preprocedural Urine Culture, Is It Safe in Clinical Practice? Urology 2020; 145: 224–228. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.07.054.

- Özmert S, Sever F, Tiryaki HT. Evaluation of the effects of sedation administered via three different routes on the procedure, child and parent satisfaction during cystometry. Springerplus 2016; 5 (1): 10 1186 40064–40016–3164–3167. DOI: 10.1186/s40064-016-3164-7.

- Chen Z, Lin M, Huang Z, Zeng L, Huang L, Yu D, et al.. Efficacy of Chloral Hydrate Oral Solution for Sedation in Pediatrics: a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [Corrigendum]. Drug Des Devel Ther 2022; Volume 16 (13): 3491–3492. DOI: 10.2147/dddt.s392339.

- Wagner AA, Godley ML, Duffy PG, Ransley PG. A Novel, Inexpensive, Double Lumen Suprapubic Catheter for Urodynamics. J Urol 2004; 171 (3): 1277–1279. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000110761.60356.44.

- Wen JG, Djurhuus JC, Rosier PFWM, Bauer SB. ICS educational module: Cystometry in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2018; 37 (8): 2306–2310. DOI: 10.1002/nau.23729.

- Gilmour RF, Churchill BM, Steckler RE, Houle A-M, Khoury AE, McLorie GA. A New Technique for Dynamic Analysis of Bladder Compliance. J Urol 1993; 150 (4): 1200–1203. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35727-0.

- Chin-Peuckert L, Komlos M, Rennick JE, Jednak R, Capolicchio J-P, Salle JLP. What is the Variability Between 2 Consecutive Cystometries in the Same Child? J Urol 2003; 170 (4 Part 2): 1614–1617. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000084298.49645.27.

- Landau EH, Churchill BM, Jayanthi VR. The sensitivity of pressure specific bladder volume versus total bladder capacity as a measure of bladder storage dysfunction. J Pediatr Surg 1994; 30 (5): 761. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90736-x.

- Tarcan T, Sekerci CA, Akbal C, Tinay I, Tanidir Y, Sahan A, et al.. Is 40 cm H2O detrusor leak point pressure cut-off reliable for upper urinary tract protection in children with myelodysplasia? Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36 (3): 759–763. DOI: 10.1002/nau.23017.

- Rosier PFWM, Schaefer W, Lose G, Goldman HB, Guralnick M, Eustice S, et al.. International Continence Society Good Urodynamic Practices and Terms 2016: Urodynamics, uroflowmetry, cystometry, and pressure-flow study. Neurourol Urodyn 2017; 36 (5): 1243–1260. DOI: 10.1002/nau.23124.

- Abrams P. Describing bladder storage function: overactive bladder syndrome and detrusor overactivity. Urology 2003; 62 (5): 28–37. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2003.09.050.

- Bauer SB, Vasquez E, Cendron M, Wakamatsu MM, Chow JS. Pelvic floor laxity: A not so rare but unrecognized form of daytime urinary incontinence in peripubertal and adolescent girls. J Pediatr Urol 2018; 14 (6): 544.e1–544.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.04.030.

- Bachelard M, Sillén U, Hansson S, Hermansson G, Jodal U, Jacobsson B. Urodynamic Pattern In Asymptomatic Infants: Siblings Of Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux. J Urol 1999; 162 (5): 1733–1738. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68226-2.

- Marks BK, Goldman HB. Videourodynamics. Urol Clin North Am 2014; 41 (3): 383–391. DOI: 10.1016/j.ucl.2014.04.008.

- Sager C, Burek C, Corbetta JP, Weller S, Ruiz J, Perea R, et al.. Initial urological evaluation and management of children with neurogenic bladder due to myelomeningocele. J Pediatr Urol 2017; 13 (3): 271.e1–271.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.12.024.

- Ngo TC, Clark CJ, Wynne C, Kennedy WA. Radiation Exposure During Pediatric Videourodynamics. J Urol 2011; 186 (4s): 1672–1677. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.014.

- De Gennaro M, Capitanucci M, Silveri M, Mosiello G, Broggi M, Pesce F. Continuous (6 Hour) Urodynamic Monitoring in Children with Neuropathic Bladder. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1996; 6 (S 1): 21–24. DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1071032.

- Lu YT, Jakobsen LK, Djurhuus JC, Bjerrum SN, Wen JG, Olsen LH. What is a representative voiding pattern in children with lower urinary tract symptoms? Lack of consistent findings in ambulatory and conventional urodynamic tests. J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (3): 154.e1–154.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.02.006.

Last updated: 2023-02-22 15:40