43: Bladder Malignancies

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 12 minutos para ler.

Introduction

Urothelial cell carcinoma (UCC) in the pediatric population is very rare with an incidence of roughly 0.1%-0.4%. A 2019 review found only 243 documented cases of UCC in patients <18y of age, with the mean age being 12.5y, and there is a male predominance (3:1). Overall, recurrence of UCC in the pediatric population is thought to be low (8.6%), and death very uncommon, <4%. Given its rarity, there are no published guidelines on the diagnosis and management of UCC in the pediatric population. This chapter aims to outline etiology and pathogenesis, evaluation and diagnosis, management, and follow up of pediatric UCC currently published literature.

Etiology/Pathogenesis

There are well-defined risk factors for UCC development in adults including smoking, exposures to various workplace chemicals such as aniline dyes and textile plant chemicals, phenacetin, and exposures to chemotherapy or radiation. Genetic conditions have also been linked to the development of bladder UCC in adults, namely Lynch syndrome, Cowden disease, and presence of UCC in first-degree relative. In children, genetic and environmental risk factors are not well studied, but extrapolated from adults. Early tobacco exposure, cancer-predisposition syndromes (e.g. Costello syndrome), abnormal bladder development, radiation exposure, cyclophosphamide exposure, and parasitic infections have been attributable risk factors for the development of UCC in children. Despite these however, no obvious known risk factors may be present in nearly 87% of pediatric patients with UCC.

Risk factors for recurrence and bladder cancer-related death in the pediatric population include family history of UCC, high-grade histology, and larger tumors at diagnosis. Recurrence and death are rare, so again, these factors are generally extrapolated from the adult literature.

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Patient Presentation

Similar to adults, pediatric patients often present with painless gross hematuria (90%) although irritative voiding symptoms such as dysuria, frequency, and urgency may also be common. Delay in diagnosis by at least 1 year has been reported in up to 26% of patients given the rarity of this diagnosis in children and the generally benign differential diagnoses for gross hematuria in a child (e.g. benign urethrorrhagia, trauma, urinary tract infections, congenital urologic anomalies, intrinsic renal disease, voiding dysfunction, etc.).

UCC typically presents as a solitary bladder tumor in children compared to multifocality in adults (94% vs. 6%). 93.4% of tumors are low-grade (pTa or pT1), and there is usually no evidence of nodal involvement or metastasis. Table 1 outlines the American Join Committee on Cancer (AJCC) bladder cancer staging.

Table 1 AJCC Urothelial cell carcinoma staging

| T stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Ta | Noninvasive papillary carcinoma |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ (CIS) |

| T1 | Tumor invades lamina propria |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria |

| T2a | Tumor invades superficial muscularis propria (inner half) |

| T2b | Tumor invades deep muscularis propria (outer half) |

| T3 | Tumor invades perivesical tissue/fat |

| T3a | Tumor invades perivesical tissue/fat microscopically |

| T3b | Tumor invades perivesical tissue fat macroscopically (extravesical mass) |

| T4 | Tumor invades prostate, uterus, vagina, pelvic wall, or abdominal wall |

| T4a | Tumor invades adjacent organs (uterus, ovaries, prostate stroma) |

| T4b | Tumor invades pelvic wall and/or abdominal wall |

Initial Evaluation

The 2020 AUA guidelines on non-muscle invasive UCC stipulate clear recommendations on evaluation of adult patients with gross hematuria including cystoscopy, upper tract imaging with CT or MR urography, and occasionally the use of urine cytology. Given the natural progression of UCC in pediatric patients, i.e. generally low grade tumors that do not recur, the initial workup of a pediatric patient with gross hematuria is often approached less aggressively.

Evaluation should begin with a history and physical exam. Additional investigative modalities at the first visit include urinalysis (with particular attention given to presence/quantity of red blood cells and indicators of infection such as leukocyte esterase, nitrites, and bacteria), urine culture, and bladder/renal ultrasound.

Urinalysis can confirm ongoing microscopic hematuria and help to rule out other potential causes of hematuria, including medical renal disease or infection. The urine culture would confirm no infection is present. Bladder/renal ultrasound can determine upper and lower tract anatomy and evaluate potential causes of gross hematuria. Given the smaller body habitus of children, this modality can be very sensitive in detecting small luminal tumors.

Imaging, Cystoscopy and Cytology

In the adult population, cystoscopy is the gold standard for the detection of bladder tumors and upper tract imaging in the form of CT or MR urography is standard to image the upper tracts. In the pediatric population there are considerations that must be weighed, including the requirement for general anesthesia for cystoscopy, sedation for imaging with CT or MRI, and radiation exposure with CT.

There have been a few studies evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound in evaluation of both upper and lower urinary tracts for detection of masses in children. Bladder ultrasound has been found to have sensitivity of 83-93% in detecting bladder tumors with 93-100% specificity and has detected bladder lesions as small as 5mm. When considering the cumulative radiation dose a pediatric patient may acquire for UCC surveillance over many years, ultrasound becomes an attractive modality both for an initial screening test upon presentation with gross hematuria but also for surveillance of mass recurrence following resection.

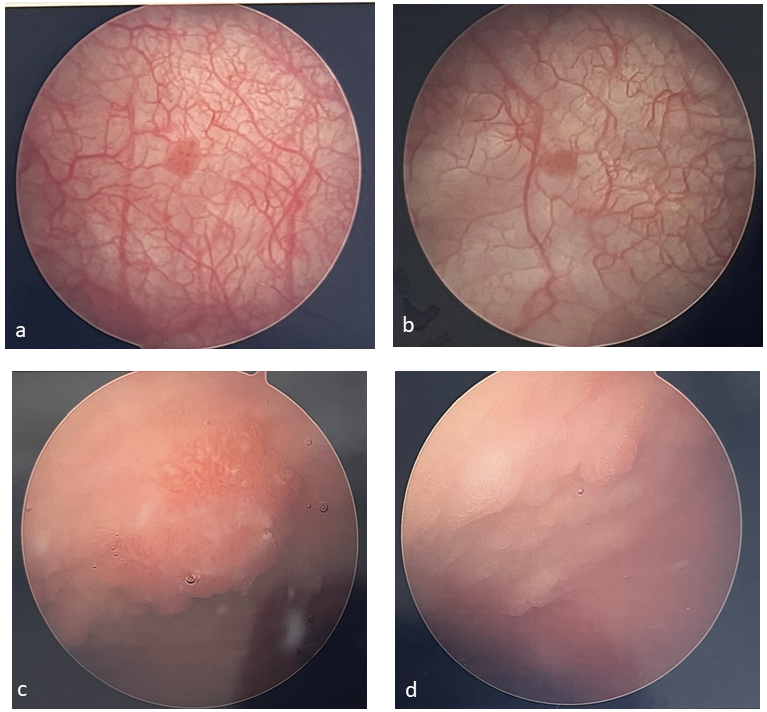

Cystoscopy is indicated for patients for whom a bladder lesion was detected on ultrasound or for those with persistent hematuria without any other explanation. In pediatric patients, tumors are usually solitary, non-invasive, and approximately 52% of them are found on the lateral walls (Figure 1) Cystoscopy in children requires anesthesia, thus cystoscopy is often performed with transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) as an expected part of the procedure. Tissue is required to establish a diagnosis and depth of invasion (T stage). This is also the initial treatment to remove the entire tumor.

Figure 1 Examples of bladder tumors. Bladder tumors are often solitary and papillary (a, b) and can be harder to identify in patients who have undergone bladder augmentation (c, d).

Figure 1 Examples of bladder tumors. Bladder tumors are often solitary and papillary (a, b) and can be harder to identify in patients who have undergone bladder augmentation (c, d).

There is minimal role for urine cytology in pediatric patients as these bladder tumors are typically low-grade and the sensitivity of cytology for low-grade tumors is quite low.

Management

Bladder cancer recurrence in the pediatric population is low and 5-year survival rates are favorable at 97.3%. Because of these differences, management differs significantly from adults. There are, however, some similarities between both populations and thus there are some shared aspects to management.

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT)

As with adults, transurethral resection is both diagnostic and therapeutic. This requires resection of all grossly evident tumor, with depth sufficient to obtain sampling of the underlying detrusor muscle. This is necessary to reduce the risk of recurrence but also for adequate staging. TURBTs that require a resectoscope may be prohibitive in small patients as resectoscope loops can be very challenging to work with on smaller scopes. Some children may require cold cup biopsy and fulguration of the tumor base, although care must be taken to obtain deep tissue biopsies for detrusor sampling. Bimanual exam of the bladder should also be performed at time of TURBT to complete staging.

Intravesical therapy

In general, perioperative chemotherapy instillation is not used for pediatric patients. Pediatric patients who are found to have higher grade and stage tumors are likely to behave more similarly to adult UCC and thus may be best treated as such, although prospective studies of this rare scenario do not exist. These patients may require intravesical chemotherapy and surveillance protocols as those for adults outlined by the AUA and NCCN organizations. There are some reports of post-TURBT use of intravesical instillation BCG, mitomycin, or epirubicin in pediatric patients with bladder cancer. Generally, doses and regimens have been that which is described in adults, with few severe adverse events. Intravesical therapy is typically reserved for patients with high-grade or recurrent disease, but data are limited to case reports, so there are no clear data to establish a well-defined role at this time.

Follow up and Surveillance

Adult guidelines have aggressive, clear, and established regimens for surveillance and management of recurrences as this is commonplace. For children however, there are no clear recommendations due to the rarity of this tumor and the even more rare recurrence. A 2019 review reported just an 8.6% recurrence rate, a significant difference from adults.

Generally, the type and timing of surveillance should be tailored based on the child’s risk of relapse. The number of lesions, pathologic stage and grade, tumor size, history of recurrence, and age should all be considered. Regular screening with ultrasound is a reasonable option for children with diagnosed bladder cancer due to its high sensitivity and non-invasive nature. Cystoscopy can subsequently be performed if a lesion is detected. Routine surveillance cystoscopy despite normal ultrasounds may be required in higher risk pediatric patients (e.g. multiple lesions, high-grade lesions, recurrence, older age, etc.). Similar to at the time of diagnosis, urine cytology is unlikely to yield much benefit given that children typically have low-grade well-differentiated tumors.

Unlike adult protocols, there are no data to guide the length of surveillance for children with UCC. One large literature review found that if a recurrence or death related to low-grade/stage UCC were to occur, it is likely to occur in the first year of initial diagnosis. The average time to recurrence or death was found to be 8.6 months.

Table 2 Surveillance schedule for low-grade, low-stage bladder UCC in pediatric patients (adapted by Rezaee et al)1

| 0-12 months | 18-24 months | 36-48 months | >60 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound | Every 3 mos | Every 6 mos | Annually | At discretion of provider |

| Urinalysis | Every 3 mos | Every 6 mos | Annually | At discretion of provider |

| Cystoscopy | Every 3 mos | Every 6 mos | +/- Annually | At discretion of provider |

| Cytology | — | — | — | — |

Additionally, it is very unlikely that a recurrence or death event would occur beyond three years after initial diagnosis and treatment. The most remote recurrence published is at 32 months after initial diagnosis. A potential surveillance schedule for low grade, low stage UCC was outlined by Rezaee et al. based on a 2019 literature review cohort, and this is summarized in Table 2. It is important to note that this surveillance schedule has not been rigorously studied by a prospective randomized study proving its safety and is outlined as a starting point for low grade/stage disease only.

Bladder Tumors in the Neurogenic Bladder Population

Long-term follow up of patients with a congenital neurogenic bladder (i.e. spina bifida, bladder exstrophy, etc.) have identified this population to be uniquely at higher risk for the development of bladder cancer (estimated incidence about 4%). Unlike bladder cancer in the non-neurogenic bladder population, this cohort is usually diagnosed incidentally and has a higher incidence of adenocarcinoma (50%). The vast majority of patients present with locally advanced or widespread disease (>70%) and survival is poor. Diagnosis is often made with late stage disease and outcomes are poor.

Initial postulation for this increased risk of bladder cancer centered around augmentation cystoplasty being a risk factor. While gastric segments certainly increase the subsequent risk of malignancy, augmentation with other bowel segments do not appear to increase the risk of malignancy. Through various retrospective studies, it now appears that the risk of malignancy is due to the congenital bladder itself rather than due to augmentation.

When early descriptions of advanced, deadly malignancies in this population were first published, a variety of measures were suggested and then studied with an aim of earlier detection of these tumors. Unfortunately, none have proven beneficial. Annual cystoscopy is of low yield and even in patients with normal screening, advanced bladder cancer did develop. It was suggested that if cystoscopy could detect every malignancy, 980 would need to be performed to diagnose a single case of cancer over 10y of follow up. Urine cytology is of little value in this population due to chronic pyuria, intermittent catheterizations, and expected enteric cell shedding and it also has a high false positive rate. When then including effectiveness of the above screening measures, is appears that the increase in life expectancy was only 2.3 months and lifetime cost was >$55,000 per capita. This is mainly driven by the low rates of malignancy and the large number of screening tests needed to detect a single case of malignancy, independent of stage at diagnosis.

The Husmann protocol has been widely adopted to guide follow up for patients with neurogenic bladder, both for malignancy detection as well as routine assessment for patients with or without bladder reconstruction (Figure 2) This involves an annual assessment of urinary tract infections, hematuria, bladder/pelvic/flank pain and new incontinence. If there are any abnormalities or changes from baseline, urine culture, cystoscopy, CT scan ± urodynamics should be considered. All patients should have annual creatinine/cystatin C, electrolytes, serum B12 level and urinalysis. Similarly, if there are <50 RBCs/hpf, renal/bladder US should be ordered. If the US is abnormal, if there is gross hematuria or ≥50 RBCs/hpf, then urine culture, cystoscopy, CT scan ± urodynamics should be considered. For patients with colonic segments, routine cystoscopy for colon cancer screening should begin at age 50y.

Figure 2 Husmann protocol for surveillance of bladder cancer in patients with bladder augmentations.2

Key Points

- Bladder cancer in pediatric patients is rare

- There are currently no well-defined risk factors for the development of pediatric bladder cancer, but the risk factors from adults are extrapolated and often applied to this population

- Most pediatric patients with bladder cancer present with painless gross hematuria or irritative voiding symptoms

- Most pediatric UCC is low-grade, low-stage, and does not recur

- Initial evaluation should start with history and physical, urinalysis, urine culture, and bladder/renal ultrasound

- Bladder ultrasound has excellent sensitivity and specificity for detection of bladder tumors and should be considered as a screening modality

- There is no role for urine cytology as most pediatric UCC is low-grade

- If a lesion is found on ultrasound, cystoscopy with TURBT should be performed

- Transurethral resection of bladder tumor should include detrusor sampling for proper staging

- The role for intravesical chemotherapy is unclear, but is a reasonable consideration for patients with high-stage, high-grade, or recurrent disease

- Pediatric patients with UCC should undergo surveillance at least for the first 3y after diagnosis, but surveillance beyond this may be unnecessary

- Patients with a congenital neurogenic bladder (CNB) are at higher risk of bladder cancer and this risk is not associated with bladder augmentation other than gastric segments; pathology is usually adenocarcinoma

- CNB patients present incidentally with higher stage and locally advanced tumors, with poor survival

- Routine screening with cystoscopy and urine cytology is not beneficial and is not recommended

- The Husmann protocol is advocated for follow up for patients with CNB with a goal of targeted identification of patients at higher risk for malignancy (hematuria, increased UTIs, pain, new incontinence, abnormal labs/imaging)

Conclusion

Bladder cancer in pediatric patients is rare and overall carries a good prognosis. Most tumors are solitary, low-grade, and do not recur. Workup should start with history and physical, urinalysis, urine culture, and bladder/renal ultrasound, with subsequent cystoscopy and TURBT of the bladder lesion. Intravesical chemotherapy can often be avoided given low-grade pathology. In high-grade or higher-stage tumors or with recurrent tumors, intravesical chemotherapy can be considered, however, there are no evidence-based guidelines on its use in children presently. Patients should be monitored for a duration of at least 3y with a combination of periodic urinalyses, bladder/renal ultrasounds, and cystoscopy. Surveillance beyond 3y may not be necessary, but shared-decision making should be utilized to determine this duration.

Recommended videos

References

- Karatzas A, Tzortzis V. Lower urinary tract symptoms and bladder cancer in children: The hidden scenario. Urol Ann 2019; 11 (1): 102–104. DOI: 10.4103/UA.UA_60_18.

- Rezaee ME, Dunaway CM, Baker ML, Penna FJ, Chavez DR. Urothelial cell carcinoma of the bladder in pediatric patients: a systematic review and data analysis of the world literature. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2019; 15 (4): 309–314. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.06.013.

- Lerena J, Krauel L, García-Aparicio L, Vallasciani S, Suñol M, Rodó J. Transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder in children and adolescents: Six-case series and review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2010; 6 (5): 481–485. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.11.006.

- Egbers L, Grotenhuis AJ, Aben KK, Alfred Witjes J, Kiemeney LA, Vermeulen SH. The prognostic value of family history among patients with urinary bladder cancer. Int J Cancer 2015; 136 (5): 1117–1124. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.29062.

- Wild P, Giedl J, Stoehr R. Genomic aberrations are rare in urothelial neoplasms of patients 19 years or younger. The Journal of Pathology 2007; 211 (1): 18–25. DOI: 10.1002/path.2075.

- Fine SW, Humphrey PA, Dehner LP, Amin MB, Epstein JI. Urothelial Neoplasms In Patients 20 Years or Younger: A Clinicopathological Analysis Using The World Health Organization 2004 Bladder Consensus Classification. Journal of Urology 2005; 174 (5): 1976–1980. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176801.16827.82.

- Paner GP, Zehnder P, Amin AM, Husain AN, Desai MM. Urothelial Neoplasms of the Urinary Bladder Occurring in Young Adult and Pediatric Patients: A Comprehensive Review of Literature With Implications for Patient Management. Adv Ant Pathol 18 (1): 79–89.

- Bladder Cancer: Non-Muscle Invasive Guideline - American Urological Association. .

- Gharibvand MM, Kazemi M, Motamedfar A, Sametzadeh M, Sahraeizadeh A. The role of ultrasound in diagnosis and evaluation of bladder tumors. J Family Med Prim Care 2017; 6 (4): 840–843. DOI: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_186_17.

- Berretini A, Castagnetti M, Salerno A. Bladder urothelial neoplasms in pediatric age: Experience at three tertiary centers. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2015; 11: 26 1–26 5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.08.008.

- D DC, A F, K P. Management and follow-up of urothelial neoplasms of the bladder in children: A report from the TREP project. Pediatric Blood & Cancer 2015; 62 (6): 1000–1003. DOI: 10.1002/pbc.25380.

- ElSharnoby O, Fraser N, Williams A, Scriven S, Shenoy M. Bladder urothelial cell carcinoma as a rare cause of haematuria in children: Our experience and review of current literature. Journal of Pediatric Surgery Published Online September 2021; 17. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.09.007.

- Saltsman JA, Malek MM, Reuter VE. Urothelial neoplasms in pediatric and young adult patients: A large single-center series. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2018; 53 (2): 306–309. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.11.024.

- Rague JT, High-grade LRSM. Nonmuscle Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma in a Prepubertal Patient With TURBT and Intravesical BCG. Urology 2019; 124: 257–259. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2018.10.028.

- Peard L, Stark T, Ziada A, Saltzman AF. Recurrent Bladder Cancer in a Teenage Male. Urology 2020; 141: 135–138. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.04.031.

- Soergel TM, Cain MP, Misseri R, Gardner TA, Koch MO, Rink RC. TRANSITIONAL CELL CARCINOMA OF THE BLADDER FOLLOWING AUGMENTATION CYSTOPLASTY FOR THE NEUROPATHIC BLADDER. The Journal of Urology 2004; 172 (4, Supplement): 1649–1652. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000140194.87974.56.

- Austin JC, Elliott S, Cooper CS. Patients With Spina Bifida and Bladder Cancer: Atypical Presentation, Advanced Stage and Poor Survival. The Journal of Urology 2007; 178 (3): 798–801. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.055.

- Rove K, Higuchi T. Monitoring and malignancy concerns in patients with congenital bladder anomalies. Current Opinion in Urology 2016; 26 (4): 344–350. DOI: 10.1097/MOU.0000000000000297.

- Husmann D, Fox J, Higuchi T. Malignancy following bladder augmentation:recommendations for long-term follow-up and cancer screening. AUA Update Ser 2011; 30 (24): 222–227.

- Higuchi TT, Fox JA, Husmann DA. Annual Endoscopy and Urine Cytology for the Surveillance of Bladder Tumors After Enterocystoplasty for Congenital Bladder Anomalies. The Journal of Urology 2011; 186 (5): 1791–1795. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.028.

- Hamid R, Greenwell TJ, Nethercliffe JM, Freeman A, Venn SN, Woodhouse CRJ. Routine surveillance cystoscopy for patients with augmentation and substitution cystoplasty for benign urological conditions: is it necessary? BJU International 2009; 104 (3): 392–395. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08401.x.

- Kokorowski PJ, Routh JC, Borer JG, Estrada CR, Bauer SB, Nelson CP. Screening for Malignancy After Augmentation Cystoplasty in Children With Spina Bifida: A Decision Analysis. The Journal of Urology 2011; 186 (4): 1437–1443. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.05.065.

Ultima atualização: 2024-02-16 21:59