38: Anomalia cloacal

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 26 minutos para ler.

Introdução

As anomalias anorretais compreendem um espectro de malformações congênitas envolvendo o reto e o ânus. Crianças com malformações anorretais (ARM) são frequentemente diagnosticadas com “ânus imperfurado” porque não há uma abertura onde a abertura anal normal deveria estar. Isso simplifica em excesso a patologia subjacente, que frequentemente envolve o sistema urogenital, a coluna vertebral e a musculatura do assoalho pélvico. Em uma extremidade do espectro estão as anomalias menores nas quais o canal anal está presente, mas o ânus encontra-se deslocado anteriormente ou coberto por pele perineal. Nas malformações mais graves, o reto não alcança o períneo e, em vez disso, conecta-se ao trato geniturinário.

A manifestação mais grave da malformação anorretal em meninas é a malformação cloacal, na qual o reto, a uretra e a vagina se unem para formar um único canal confluente que se abre no períneo. Classicamente, o orifício perineal em uma cloaca é anterior no períneo, no local onde a uretra normalmente se abriria. As anomalias cloacais posteriores são uma variante rara em que o orifício está desviado posteriormente, com o seio urogenital inserindo-se em ou imediatamente anterior a um reto ortotópico.1,2

Embriologia e Epidemiologia

A malformação cloacal ocorre em aproximadamente 1 em cada 25.000–50.000 nascidos vivos. A causa embriológica não é completamente compreendida, mas envolve falha na divisão da cloaca primitiva pelo septo uroretal e pelas pregas de Rathke no início da gestação.3 A septação cloacal anômala está associada ao desenvolvimento anormal de outros sistemas de órgãos que se formam em estreita proximidade temporal e espacial, incluindo vértebras, uréteres, rins e derivados do ducto de Müller. Quando uma criança nasce com uma MAR, há um risco de 1% de que irmãos futuros tenham uma MAR.4

Na malformação cloacal, a vagina, o reto e a uretra são combinados em um único canal comum. Hidrocolpo pode desenvolver-se quando a vagina se enche de urina e muco, e a cavidade vaginal distendida pode causar obstrução do trato urinário por meio de compressão externa dos uréteres ou da saída da bexiga. Pacientes com um canal comum longo (> 3 cm) têm maior probabilidade de apresentar displasia sacral e anomalias congênitas adicionais, musculatura esfincteriana retal e urinária deficiente, e têm maior probabilidade de necessitar de reconstrução cirúrgica mais complexa, incluindo reconstrução vaginal.

Patogénese e Anomalias Associadas

As anomalias urológicas em pacientes com malformações anorretais são comuns e amplamente subestimadas. São particularmente prevalentes em meninas com malformação cloacal. Pediatras, cirurgiões pediátricos e urologistas devem estar cientes da alta incidência de comorbidade urológica nesses pacientes, e todos os pacientes devem ser rastreados para anomalias geniturinárias. As taxas relatadas de anomalias geniturinárias associadas em pacientes com ARM variam amplamente de 18 a 85%.5 Essa variabilidade pode ser amplamente atribuída a diferenças na completude do rastreamento. A maioria das séries com protocolos ativos de rastreamento relata uma prevalência de cerca de 50% em todos os tipos de ARM, com taxas crescentes de anomalias urológicas nos subtipos de ARM mais graves.6 As malformações cloacais são o subtipo mais grave de malformação anorretal feminina, e a grande maioria desses pacientes terá comorbidades geniturinárias (Tabela 1). Isso ressalta a importância de incluir urologistas como membros centrais da equipe multidisciplinar necessária para o cuidado de pacientes com malformações anorretais.5,7

Tabela 1 Prevalência de anomalias urológicas em 712 crianças com malformações anorretais tratadas no Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio. A prevalência da maioria das anomalias urológicas relatadas aumenta à medida que aumenta a gravidade da ARM. Entre colchetes, são apresentados intervalos de prevalência, variando de ARM leve (perineal) a ARM grave (cloaca de canal longo no sexo feminino, fístula do colo vesical no sexo masculino). As anomalias sem diferenças entre os tipos de ARM são assinaladas com um asterisco, e nenhum intervalo é apresentado. Disfunção do trato urinário inferior e anomalias müllerianas não foram incluídas nesta análise. Adaptado de Fuchs et al 2021.6

| Anomalia urológica | Cloaca < 3 cm (n=55) |

Cloaca > 3 cm (n=60) |

|---|---|---|

| >1 diagnóstico urológico | 72.7% | 93.9% |

| >2 diagnóstico urológico | 36.4% | 71.7% |

| Hidronefrose | 47.3% | 76.7% |

| Refluxo vesicoureteral | 21.8% | 31.8% |

| Rim único | 12.7% | 25.0% |

| Anomalia de fusão renal | 7.3% | 11.7% |

| Rim duplicado | 5.5% | 8.3% |

Anomalias do Trato Urinário Superior

Anomalias anatómicas coexistentes do trato urinário superior e inferior ocorrem em 50–60% dos pacientes com malformações anorretais. As anomalias observadas com maior frequência incluem hidronefrose, refluxo vésico-ureteral, displasia renal, agenesia, duplicação e variantes ectópicas, incluindo ectopia renal simples, ectopia renal cruzada com fusão, rins em ferradura e ectopia ureteral. O padrão de anomalias do trato urinário superior (juntamente com anomalias genitais masculinas) proveniente de um estudo recente e robusto de uma única série está resumido na Tabela 1.6

Além das anomalias estruturais, foi relatado que quase 50% das meninas com anomalias cloacais desenvolvem comprometimento renal grave. Consequentemente, a detecção precoce do comprometimento renal é fundamental, assim como a monitorização e o manejo proativos do trato urinário inferior.8

Disfunção do Trato Urinário Inferior

Disfunção vesical é comum entre todos os pacientes com ARM. Isso geralmente está associado a uma anomalia espinhal concomitante; contudo, algumas crianças terão disfunção vesical congênita com sacro ósseo e medula espinhal normais.9,10 Particularmente na malformação cloacal, a disfunção vesical adquirida pode resultar de lesão neuromuscular durante o reparo cirúrgico da malformação anorretal.11,12 Embora uma técnica cirúrgica meticulosa e a minimização do eletrocautério monopolar sejam prudentes, algumas lesões neuromusculares podem ser inevitáveis devido à localização mais medial do plexo autonômico pélvico em pacientes com ARM.13 Embora o rastreamento com urofluxometria provavelmente seja adequado para pacientes com ARM leves e imagem espinhal normal, defendemos que todas as meninas com anomalias cloacais sejam submetidas à avaliação urodinâmica.

Anomalias Genitais

Anomalias do trato genital feminino são menos prontamente aparentes ao exame externo, ainda assim as anomalias müllerianas são muito comuns entre meninas com ARM.14 Malformações cloacais estão associadas a taxas muito elevadas de anomalias da genitália interna, com relatos variando de 53 a 67%.15 Algum grau de duplicação mülleriana é comumente observado, variando de septos vaginais até duplicação uterina e vaginal completa. As estruturas müllerianas também podem ser subdesenvolvidas, e é comum haver assimetria em tratos reprodutivos duplicados. Delinear a anatomia mülleriana em meninas com ARM é fundamental. Hidrocolpos é comum e pode levar a dor, uropatia obstrutiva, infecção e infertilidade. Os clínicos devem avaliar e tratar o hidrocolpos em recém-nascidos, nos quais o fluido vaginal é principalmente urina acumulando-se no trato reprodutivo, e novamente em pacientes púberes após a menarca, nos quais produtos menstruais podem acumular-se na(s) vagina(s). As taxas de obstrução menstrual são relatadas em torno de 40%.8 Nesses pacientes, a obstrução vaginal pode ser congênita ou devida a estenose vaginal, que é comum após anorectovaginouretraplastia sagital posterior (PSARVUP).14,16

Anomalias da coluna vertebral

Aproximadamente um quarto a um terço dos pacientes com ARM terão patologia vertebral ou de medula espinhal associada.17,18,19 Entre pacientes com malformação cloacal especificamente, pequenas séries sugerem taxas muito mais altas de anomalias espinhais (acima de 70%), embora uma revisão retrospectiva grande e recente relate que 42% desses pacientes têm patologia espinhal.20,21 Anomalias comuns incluem medula ancorada, hipoplasia sacral, hemissacro (que está associado a uma massa pré-sacral. As patologias espinhais podem levar a complicações urológicas, neurológicas e ortopédicas.17 A realização rotineira de exames de imagem da coluna é o padrão de cuidado, e crianças com patologias espinhais precisam ser monitoradas quanto à bexiga neurogênica.

Associação VACTERL

Várias síndromes e doenças genéticas foram descritas que incluem malformações anorretais como uma característica. A mais significativa delas é a associação VACTERL, embora muitas outras tenham sido descritas. VACTERL é um acrônimo para vertebrais, anomalias, anorretais, anomalias, cardíacas, anomalias, fístula traqueoesofágica, renais, anomalias, e l anomalias dos membros. A maioria dos casos é esporádica, e não hereditária. Nem todos os componentes da associação VACTERL se manifestam em todos os pacientes. As mais comuns são as anomalias vertebrais, anorretais e renais. Para diagnosticar a associação VACTERL/síndrome VACTER, pelo menos 3 dos defeitos devem estar presentes.22 Outras síndromes que podem estar comumente associadas às malformações anorretais incluem MURCS (aplasia dos ductos müllerianos, aplasia renal e displasia dos somitos cervicotorácicos), OEIS (onfalocele, extrofia, ânus imperfurado e defeitos da coluna vertebral).23

Avaliação e Diagnóstico

Pré-natal

A malformação cloacal pode ser diagnosticada no pré-natal devido ao aumento da incidência de anomalias concomitantes e hidrocolpos. A vantagem do diagnóstico pré-natal é dupla; os pais podem receber aconselhamento, e podem ser feitos arranjos para realizar o parto em um centro familiarizado com o manejo neonatal de malformações anorretais. Pistas na ultrassonografia pré-natal incluem alça intestinal dilatada, mecônio calcificado, ausência de mecônio no reto, hidrocolpos (geralmente identificado como uma estrutura cística pélvica e uma bexiga de difícil visualização), anomalias renais, defeitos do tubo neural e ausência de rádio, entre outros. Anormalidades em múltiplos sistemas podem reforçar a suspeita de VACTERL ou de outra síndrome com anomalias anorretais. Alguns centros têm recorrido à ressonância magnética pré-natal na esperança de confirmar o diagnóstico, embora isso também seja imperfeito e não constitua o padrão atual de cuidado.24,25

Exame Físico

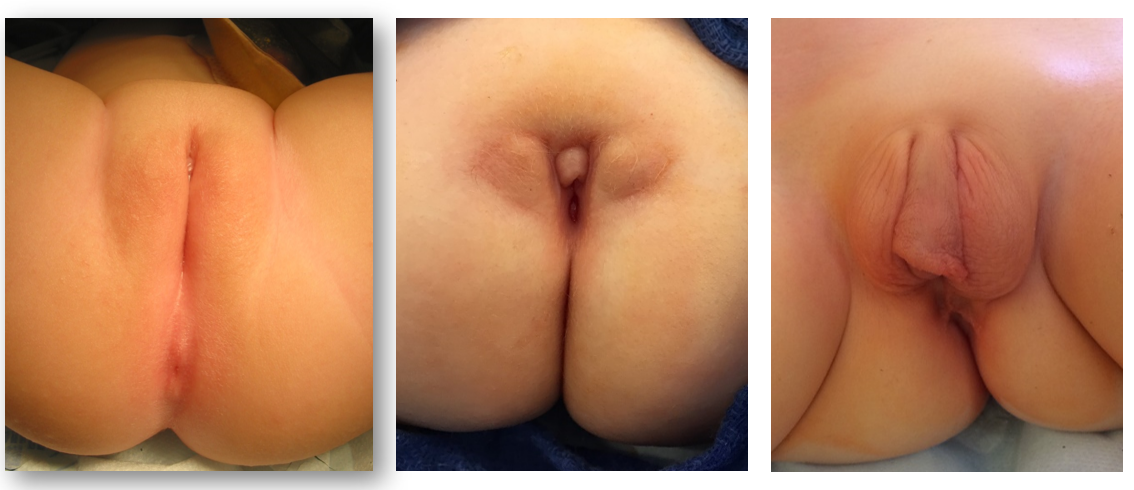

Embora o diagnóstico pré-natal de malformação cloacal possa ser suspeitado em exames de imagem pré-natais, a confirmação do diagnóstico baseia-se no exame físico no período pós-natal. Ao abordar o exame perineal e genital, os urologistas devem avaliar o número e a localização das aberturas perineais, bem como a fenda glútea. Em meninas, devem existir três aberturas perineais distintas (uretra, vagina, ânus), com o orifício anal centrado no complexo do esfíncter anal e separado da vagina pelo corpo perineal. Um único orifício perineal em uma menina é patognomônico de cloaca e é tipicamente encontrado na localização esperada da uretra. Pode haver ampla variação na aparência do períneo, mas o orifício único é o achado crítico no exame (Figura 1). Uma variante menos comum da malformação cloacal, chamada variante cloacal posterior, apresenta uma abertura perineal mais posterior, onde a vagina ou o ânus estariam localizados (Figura 2). Ocasionalmente, pele prepucial proeminente dará a aparência de clitoromegalia. Na ausência de corpos cavernosos palpavelmente aumentados, isso não deve motivar avaliação endocrinológica de rotina para condições intersexo.26

Figura 1 Fotografias perineais de meninas com malformação cloacal. O orifício anal está ausente, e a única abertura perineal localiza-se posteriormente ao clitóris, próxima da localização esperada da uretra. Tecido prepucial redundante é comum.

Figura 2 Anomalia cloacal posterior, com a única abertura perineal deslocada posteriormente em direção à localização esperada do ânus.

Exames laboratoriais e de imagem

A investigação subsequente concentra-se na avaliação de possíveis anomalias associadas.

Ecocardiograma

Isto é necessário para avaliar anomalias cardíacas estruturais, particularmente antes da anestesia.

Ultrassonografia Abdominal Completa

Avalie quanto a anomalias renais, obstrução do trato urinário, hidrocolpos e duplicação mülleriana.

Imagem da coluna vertebral

A ultrassonografia da coluna deve ser realizada, principalmente para avaliar a medula ancorada. A radiografia simples é útil para avaliar o sacro após a ossificação do cóccix. Radiografias do sacro nas incidências anteroposterior e lateral podem demonstrar anomalias sacrais, como hemissacro e hemivértebras sacrais, e permitir a avaliação do grau de hipoplasia sacral. Em geral, hipoplasia mais grave pressagia piores desfechos de continência.27 A mensuração do “índice sacral” foi proposta como indicador prognóstico para a continência intestinal, mas não se mostrou confiável como preditor de continência urinária, desenvolvimento de bexiga neurogênica ou necessidade de cateterismo intermitente.28

Para pacientes com anomalias espinhais, deve-se realizar avaliação neurocirúrgica e ressonância magnética da coluna, e esses pacientes necessitam de acompanhamento urológico contínuo para bexiga neurogênica. Crianças que se apresentarem após 3–4 meses de idade precisarão de ressonância magnética da coluna, pois a ossificação dos arcos vertebrais obscurece a janela ultrassonográfica.

Avaliação da função renal

Obter creatinina sérica para avaliar a função renal basal. Observe que a avaliação da função renal em crianças é imperfeita, e a imaturidade renal nos neonatos pode levar à subestimação da função renal, particularmente nos prematuros. A cistatina C tem sido cada vez mais utilizada como parâmetro correlato à creatinina sérica.

Exames de imagem adicionais são comumente solicitados conforme a indicação clínica. No contexto de hidronefrose decorrente de hidrocolpo ou distensão vesical, deve-se repetir a ultrassonografia renal após a drenagem do hidrocolpo para confirmar a melhora da hidronefrose. Cintilografia renal ou urografia por ressonância magnética podem ser consideradas se houver preocupação com drenagem renal deficiente ou para determinar a função renal relativa. A VCUG pode rastrear refluxo vesicoureteral, embora seja debatido o papel da realização rotineira de cistouretrografia miccional pré-operatória e pode ser difícil cateterizar a bexiga às cegas. Por fim, embora haja alta incidência de achados urodinâmicos anormais, os estudos urodinâmicos não precisam ser realizados até depois da reconstrução cirúrgica.

Planejamento pré-operatório

O restante da investigação diagnóstica é dedicado a definir a anatomia em preparação para a reconstrução cirúrgica.

Colostograma

Um colostograma distal de alta pressão definirá o nível da fístula retal, avaliará o comprimento do cólon distal disponível para o pull-through e definirá a relação do reto com o sacro e o cóccix. Após a confecção da colostomia, um cateter de Foley é inserido na fístula mucosa e o balão é insuflado suavemente para prevenir extravasamento. O contraste é então instilado através do cateter para opacificar o cólon distal. A pressão do contraste instilado deve ser adequada para vencer o tônus dos músculos elevadores do ânus, e o contraste deve ser hidrossolúvel e isosmótico devido ao raro risco de perfuração do cólon. Alternativamente, pode-se utilizar o “invertograma” para investigar a extensão do defeito na atresia anal ou retal. O ânus é marcado com marcador radiopaco, o bebê é invertido de modo que o ar no reto suba ao ponto mais alto, e realiza-se uma radiografia lateral. A distância entre o ar e o marcador radiopaco indica a distância do reto até a pele perineal.

Endoscopia

A cistoscopia e a vaginoscopia são essenciais para o planejamento pré-operatório da correção de uma cloaca ou seio urogenital. Isso pode ser coordenado com colostomia derivativa ou outro procedimento para evitar anestesia desnecessária. A endoscopia definirá o comprimento do canal comum e a distância do colo vesical até a confluência, caracterizará o colo vesical e o complexo esfíncteriano, e avaliará a bexiga e os uréteres. A ausência de óstios ureterais ortotópicos deve suscitar suspeita de ureter ectópico. A vaginoscopia revelará a presença de septo vaginal, duplicação vaginal e o tamanho da(s) vagina(s) para futura reconstrução.

É particularmente importante estabelecer a localização da confluência vaginal em relação ao colo vesical.29 Essa distância representa o comprimento uretral e tem implicações para a correção cirúrgica e os desfechos de continência.30 Um comprimento uretral mais curto indica uma malformação mais grave.29

Genitografia

Genitografias fluoroscópicas são comumente usadas para delinear as estruturas urológicas, ginecológicas e retais. Um cateter de Foley é inserido no orifício perineal e o contraste é instilado. Estudos fluoroscópicos bidimensionais convencionais estão sujeitos à sobreposição de estruturas opacificadas e, portanto, são limitados na capacidade de definir relações tridimensionais e obter medidas precisas, ressaltando a necessidade de avaliação endoscópica. Muitos centros agora empregam tomografia computadorizada tridimensional ou ressonância magnética para delinear a anatomia em malformações complexas (Figura 3).31,32

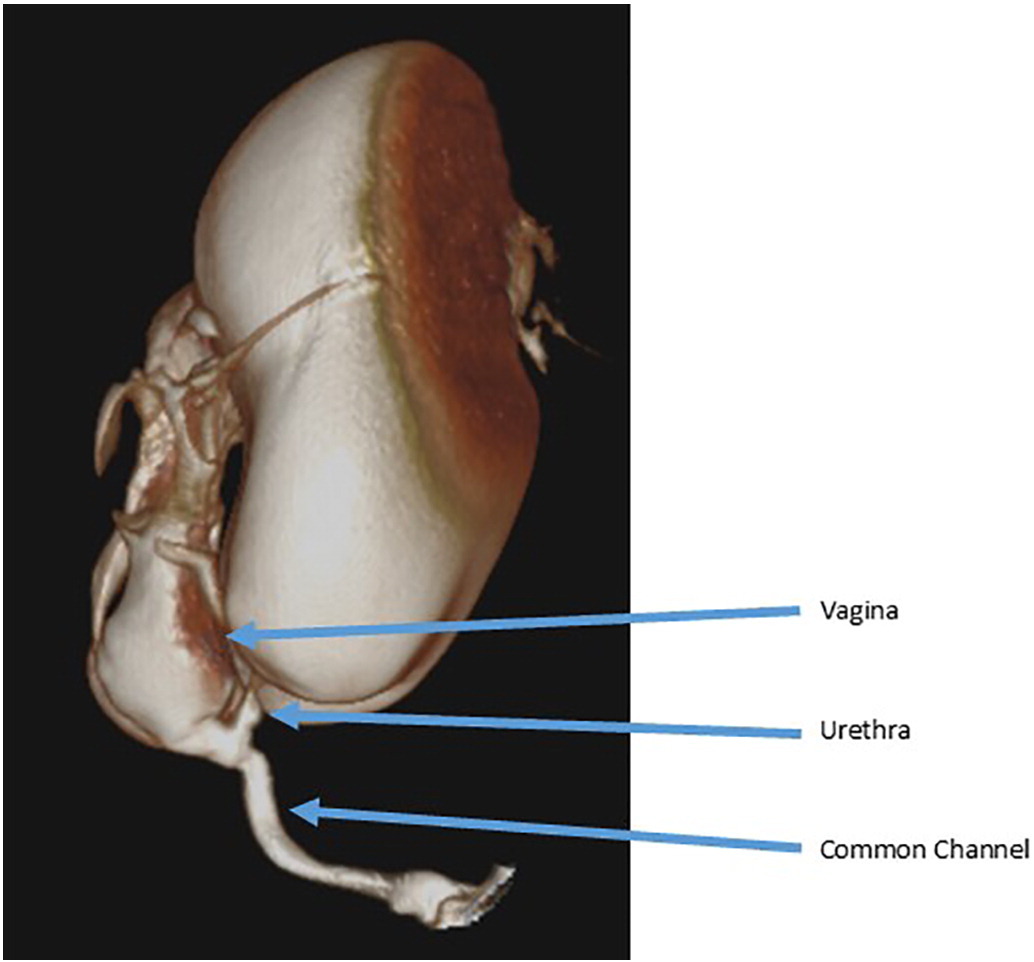

Figura 3 Exemplo de cloacograma tridimensional mostrando um canal comum longo com confluência vaginal alta e uretra curta.

Um cloacograma tridimensional (ou ressonância magnética pélvica padrão) também é útil para delinear a anatomia mülleriana e a ectopia ureteral. Os urologistas devem estar cientes de uma condição conhecida como hemivagina obstruída e anomalia renal ipsilateral (OHVIRA), na qual uma hemivagina está obstruída, de modo que a vaginoscopia demonstrará uma única vagina e colo uterino. A sugestão de anomalias müllerianas no ultrassom que seja discordante da endoscopia deve ser investigada mais a fundo, e os genitais internos devem ser inspecionados diretamente quando houver oportunidade, como no momento da colostomia derivativa inicial.16

Opções de tratamento, desfechos e complicações

Período neonatal

É fundamental, no período neonatal, garantir a reanimação adequada do recém-nascido e a descompressão dos sistemas orgânicos obstruídos. O manejo inicial deve incluir uma colostomia e uma fístula mucosa no período neonatal, tipicamente nas primeiras 24–48 horas de vida. Isso permite a descompressão do cólon e a separação do fluxo fecal do trato urinário.

Manejo do hidrocolpos

Hidrocolpos e bexiga distendida com líquido são comuns em meninas com malformação cloacal e desenvolvem-se quando a urina reflui pela vagina como resultado de obstrução urinária distal. A dilatação vaginal pode ser suficientemente grave para causar obstrução do trato urinário superior, e a urina pode refluir pelas trompas de Falópio, causando ascite urinária. Não há consenso sobre o manejo do hidrocolpos no período neonatal, mas ele requer drenagem se houver uropatia obstrutiva. Tradicionalmente, a drenagem tem sido obtida com descompressão cirúrgica por meio de uma vaginostomia, tubo de vaginostomia percutâneo ou vesicostomia. Mais recentemente, tem sido utilizada a opção menos invasiva de cateterismo intermitente limpo do canal comum.33 Quando o canal comum é cateterizado, o cateter geralmente entra preferencialmente na vagina em vez da bexiga. Em uma comparação dos dois métodos de descompressão, cirúrgico e CIC, não houve diferença na evolução da creatinina, fornecendo boa evidência de que o CIC é uma boa opção inicial, não invasiva, para descompressão do hidrocolpos.33 Se houver um septo vaginal, uma vaginostomia pode drenar apenas um lado da vagina e descomprimir inadequadamente o sistema. Nesse caso, uma vaginostomia do outro lado da vagina ou incisão do septo vaginal pode permitir melhor drenagem.

Um princípio importante de todos os métodos de descompressão do hidrocolpo é o acompanhamento para confirmar o sucesso da drenagem. Após iniciar CIC para hidrocolpo, a ultrassonografia deve confirmar a descompressão da vagina e a resolução da dilatação do trato urinário. Se não houver sucesso, deve-se considerar uma opção mais invasiva. Se a hidronefrose persistir apesar da descompressão da vagina, a investigação de outras causas de hidroureteronefrose deve ser concluída e deve-se suspeitar de bexiga neurogênica.

Manejo vesical

Muitas meninas com malformação cloacal não precisarão de nenhuma intervenção para o esvaziamento vesical. Se for identificada uma bexiga hostil ou de alta pressão com esvaziamento incompleto, pode-se criar uma vesicostomia cutânea para permitir a descompressão adequada do trato urinário. O cateterismo intermitente limpo geralmente não é possível porque, como mencionado acima, o cateter entra preferencialmente na vagina, pois a origem da uretra é comumente anterior. A vesicostomia também pode estar indicada em meninas com refluxo vesicoureteral de alto grau ou infecções recorrentes. Novamente, a drenagem e a descompressão do trato urinário precisam ser confirmadas por ultrassonografia.

Correção Cirúrgica da Malformação Cloacal

Momento da Correção

Com os sistemas orgânicos obstruídos descomprimidos, o reparo cirúrgico primário da malformação cloacal não precisa ocorrer imediatamente. Esse atraso permite um período adequado de vínculo entre a família e a criança, mas também fornece tempo para reunir a equipe multidisciplinar envolvida no cuidado da criança. Esse período também permite otimizar a nutrição e a força. Não há consenso sobre a idade ideal para o reparo, mas o reparo < 6 meses após o nascimento demonstrou ter maior taxa de complicações pós-operatórias, especificamente deiscência da ferida, e a maioria concorda que 6–12 meses de idade parece ser a idade ideal para o reparo primário.34

Técnicas Cirúrgicas

A abordagem cirúrgica é determinada pela anatomia observada no cloacograma e na cistovaginoscopia. Existem duas técnicas cirúrgicas utilizadas para a correção: mobilização urogenital total e separação urogenital. Os princípios da correção cirúrgica são mobilizar a uretra, a vagina e o reto até o períneo para que existam três orifícios separados. Isso é feito por meio de uma incisão sagital posterior e pode ser realizado em combinação com uma laparotomia, se necessário. A via sagital posterior com o bebê em posição prona é a abordagem inicial. Esse posicionamento permite melhor visualização da anatomia em comparação com a litotomia. Primeiro, o reto é identificado ao entrar no canal comum e é mobilizado superiormente até a reflexão peritoneal. Nesse ponto da operação, realiza-se uma mobilização urogenital total ou uma separação urogenital.

Separação Urogenital

A separação urogenital foi a técnica inicial descrita para o reparo da malformação cloacal e foi a abordagem padrão popularizada por Hendren (Figura 4, Figura 5, Figura 6, Figura 7, Figura 8, Figura 9, Figura 10).35 Ela permanece a abordagem de escolha para meninas com canal comum > 3 cm de comprimento. Na separação urogenital, o reto, a vagina e a uretra são separados e trazidos individualmente ao períneo. Após o reto ser descolado do canal comum, a vagina é então cuidadosamente dissecada, liberando-a da parede posterior da uretra, do colo vesical e da bexiga. O defeito na uretra no local de onde a vagina foi mobilizada é então fechado primariamente sobre um cateter. Essa dissecção pode ser desafiadora, e deve-se tomar cuidado para não devascularizar ou desnervar o trato urinário. A vagina deve ser mobilizada superiormente o máximo possível para que alcance a pele perineal sem tensão. Se a vagina não alcançar, pode ser necessária uma abordagem abdominal para maximizar a mobilização. Quando a vagina alcançar a pele, a vagina é trazida até a pele perineal, fixada posteriormente à uretra e então contornada lateralmente para criar o neo-introito. O corpo perineal é então recriado, e o reto colocado dentro do complexo muscular. Se, mesmo após a mobilização, a vagina ainda não alcançar, há técnicas adicionais de vaginoplastia descritas, como a técnica de switch vaginal, um enxerto de interposição intestinal ou até mesmo trazer a vagina nativa sob tensão, com a expectativa de que possa fibrosar e exigir introitoplastia ou vaginoplastia com mucosa bucal no início da puberdade. A decisão sobre a técnica de vaginoplastia é uma discussão multidisciplinar entre ginecologia, cirurgia colorretal e urologia e deve envolver discussão pré-operatória com a família.

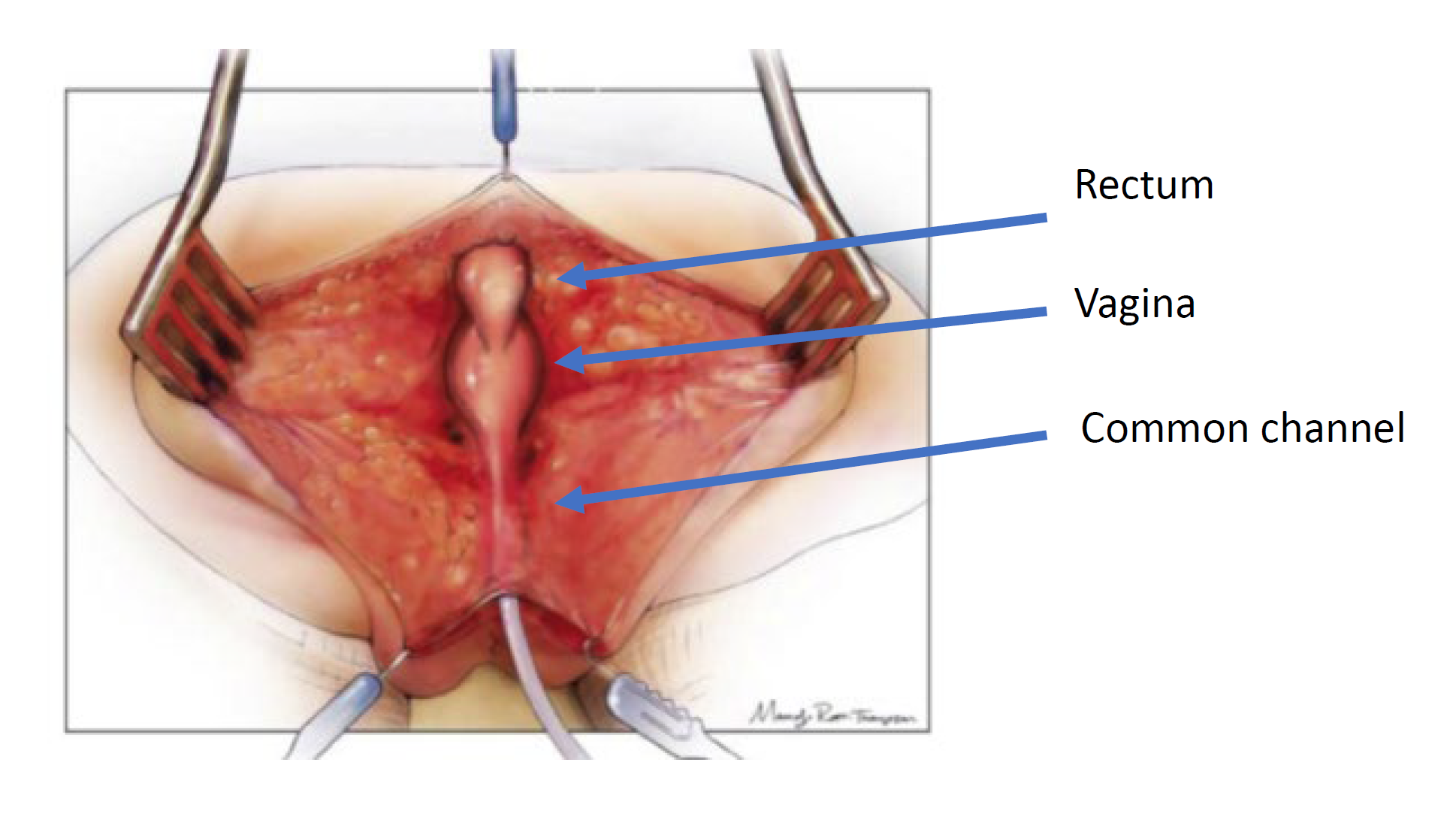

Figura 4 Ilustração de uma separação urogenital. A paciente está em posição prona, e foi realizada uma incisão sagital posterior, expondo as superfícies posteriores do reto, da vagina e do canal comum. (continua na Figura 5)

Figura 5 O reto foi dissecado da confluência vaginal, deixando uma abertura na vagina. (continuação de Figura 4, continua em Figura 6)

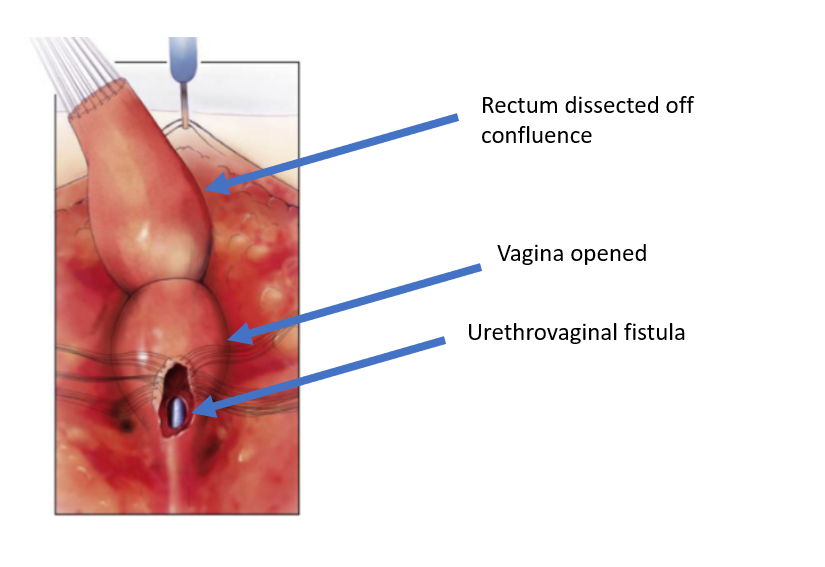

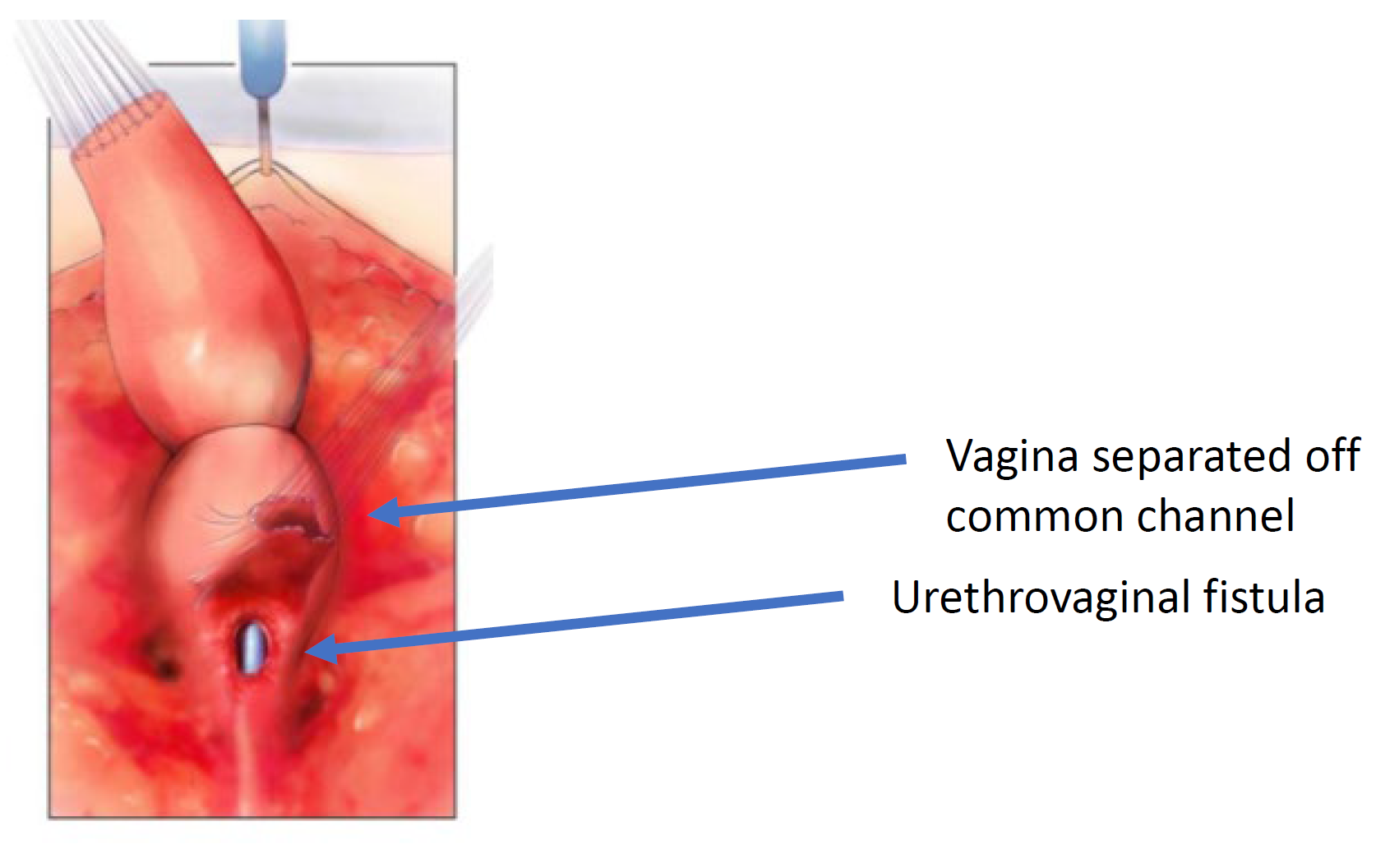

Figura 6 A vagina foi dissecada do canal comum no ponto de confluência com a uretra. A abertura pela qual se visualiza o cateter é a fístula uretrovaginal. (continuação de Figura 5, continuação em Figura 7)

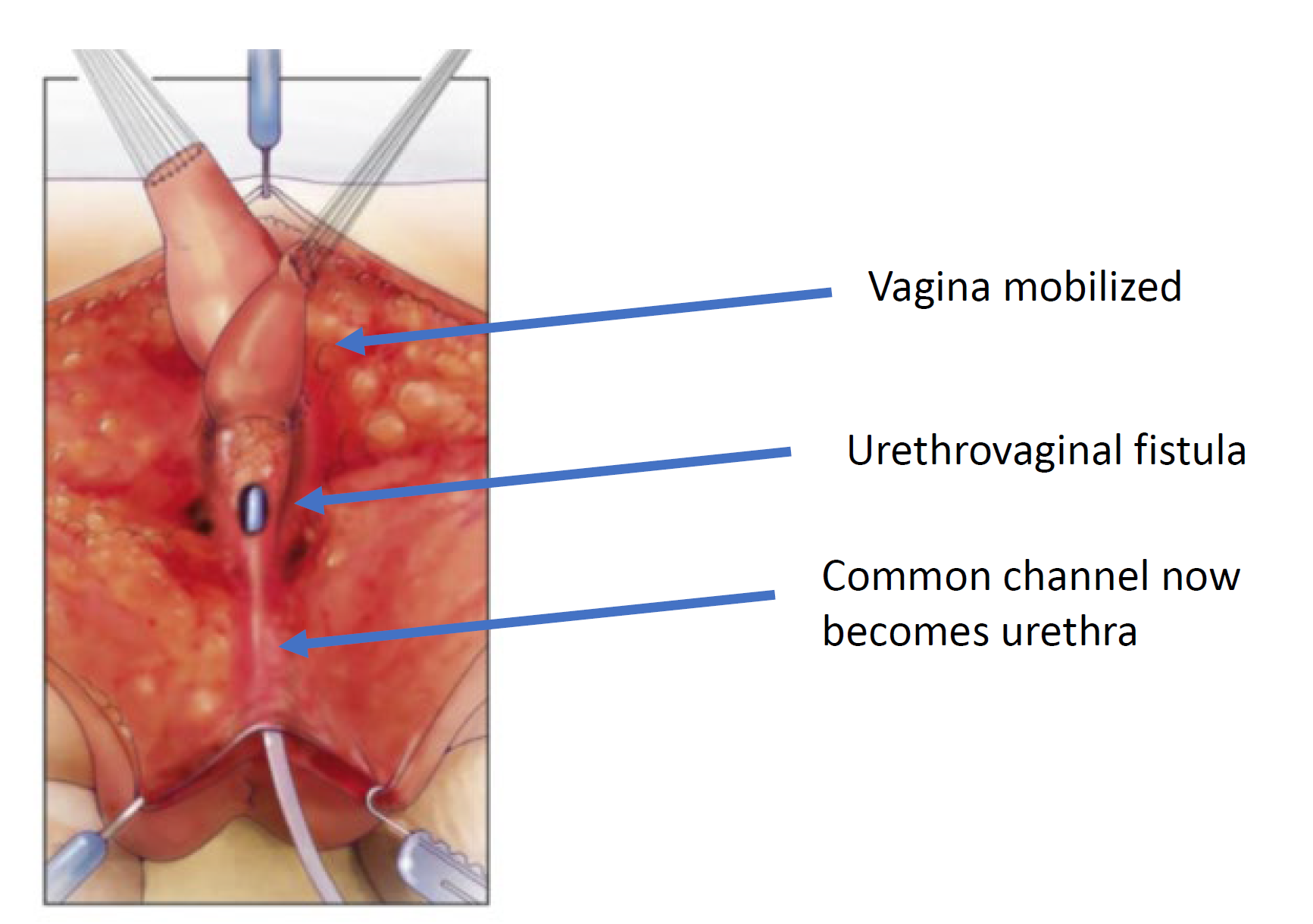

Figura 7 A vagina é mobilizada proximalmente para ganhar comprimento e elasticidade de modo que possa alcançar o períneo. (continuação de Figura 6, continua em Figura 8)

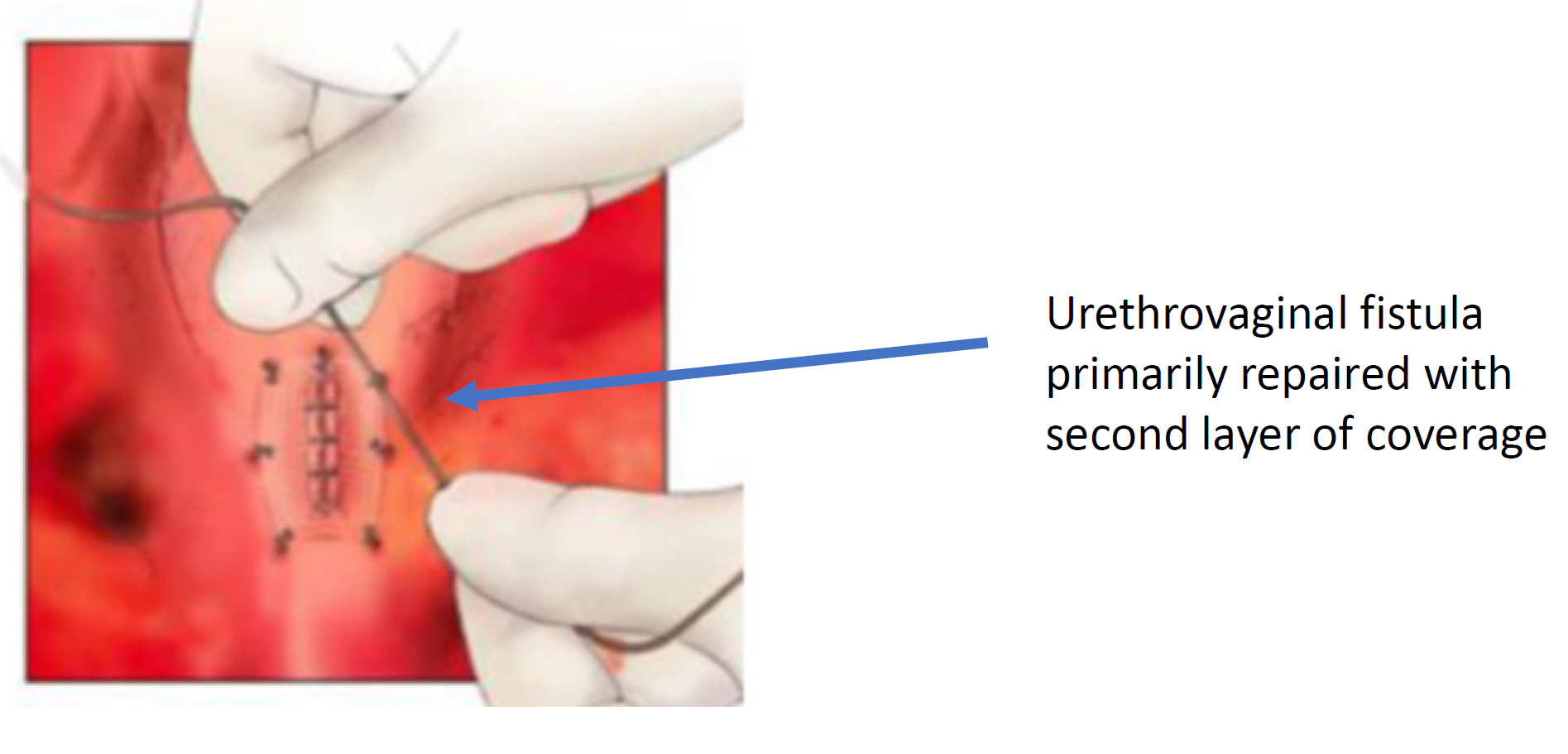

Figura 8 A fístula uretrovaginal está fechada. (continuação da Figura 7)

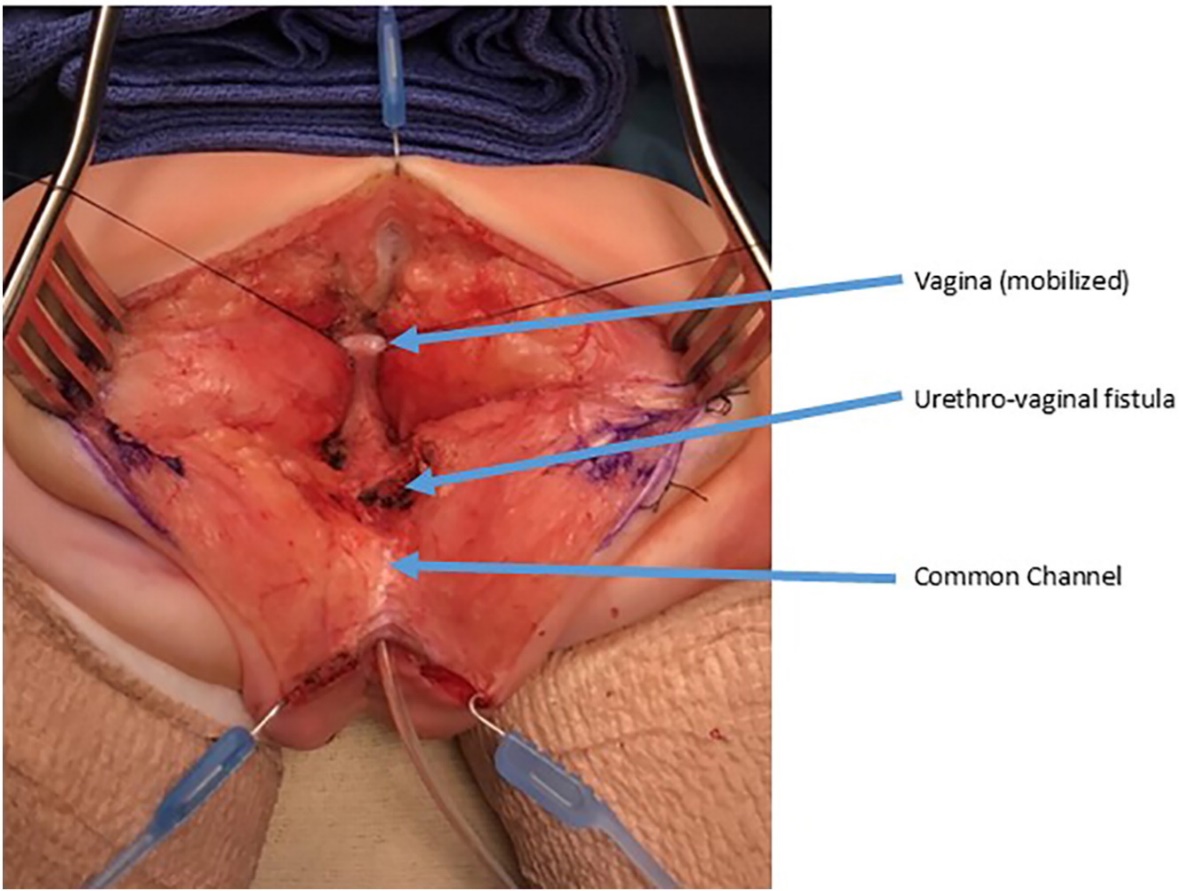

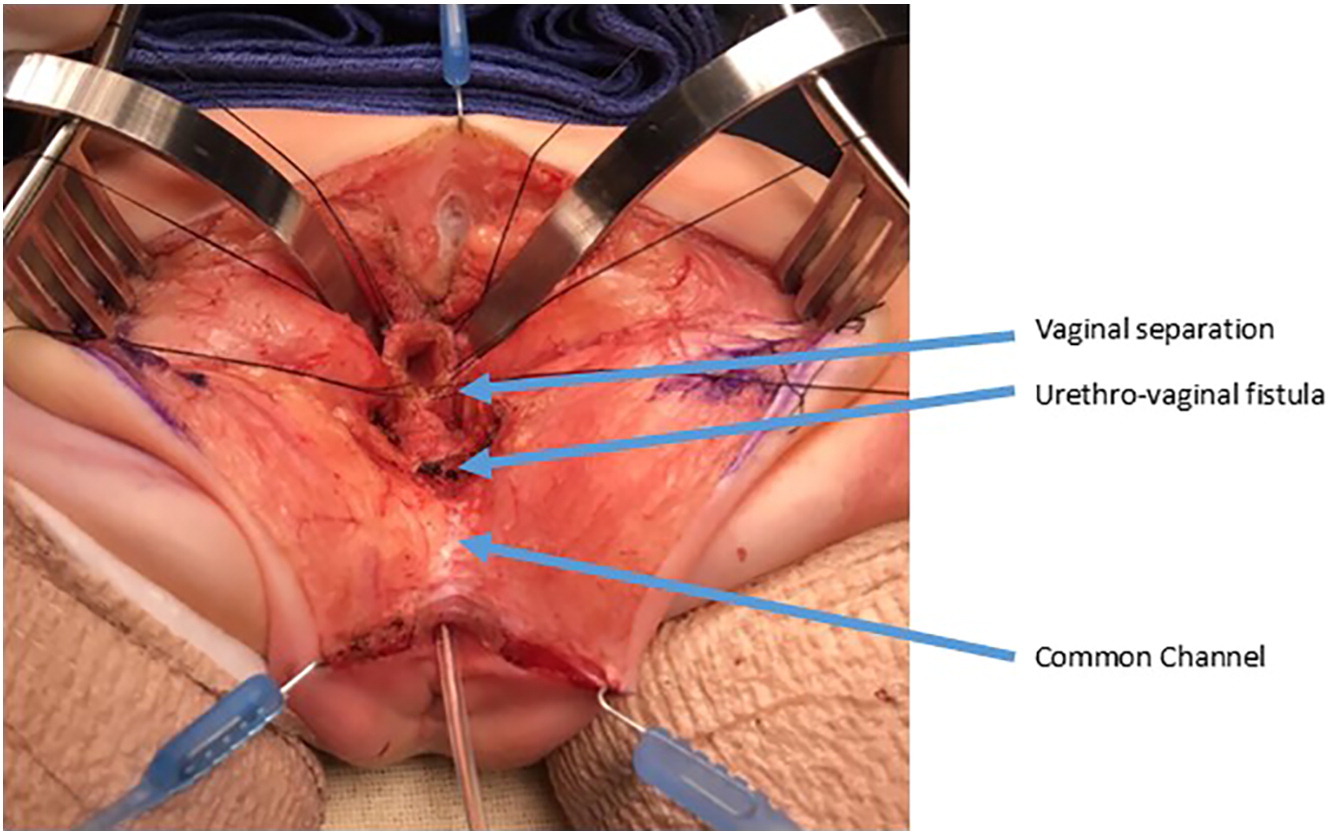

Figura 9 Fotografias intraoperatórias de uma separação urogenital. Foi realizada uma incisão sagital posterior. Há um cateter no canal comum. A vagina é mantida com suturas de tração. A confluência da vagina e da uretra está identificada como fístula uretrovaginal, que será fechada após separar a vagina da uretra. (continua na Figura 10)

Figura 10 Fotografias intraoperatórias de uma separação urogenital. A vagina foi aberta e separada da uretra. A vagina será então mobilizada proximalmente para ganhar comprimento e alcançar o períneo. A fístula uretrovaginal está novamente rotulada e será fechada primariamente, em camadas, sobre um cateter. (continuação da Figura 9)

Mobilização Urogenital Total

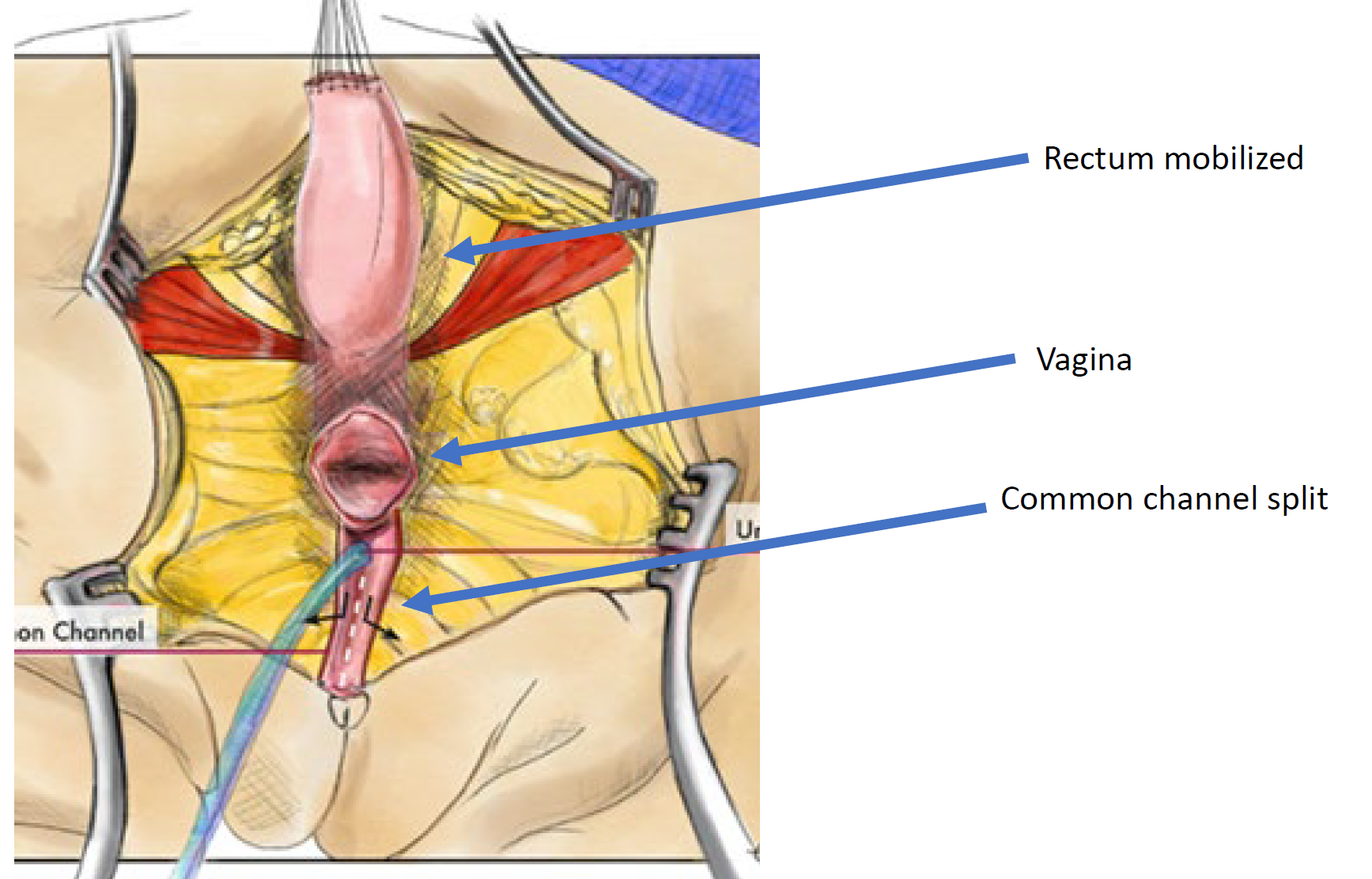

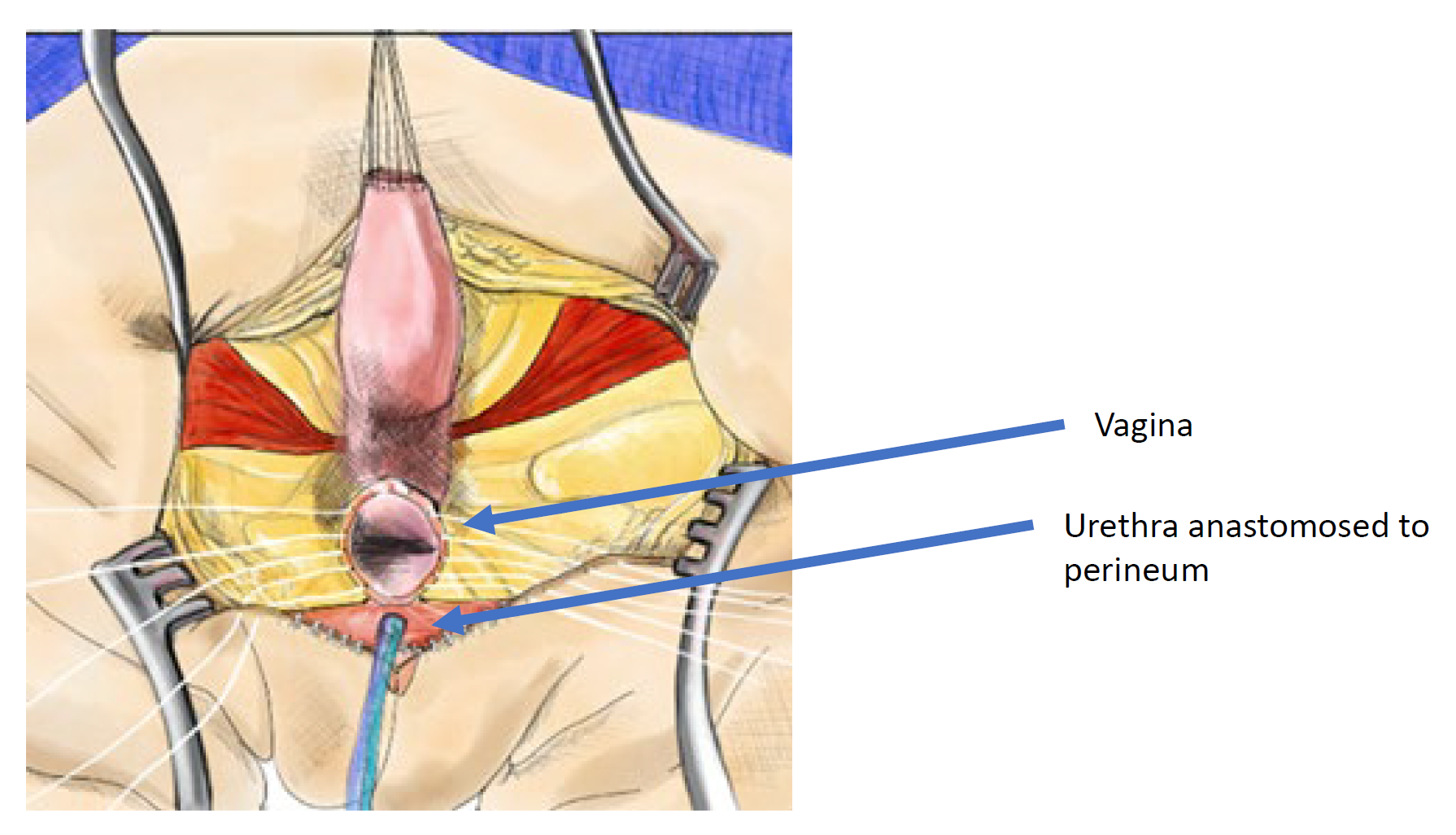

A mobilização urogenital total foi introduzida pela primeira vez para reparo cloacal por Peña em 1997 e foi considerada uma “abordagem mais fácil para a cloaca” porque não requer separar a vagina do trato urinário (Figura 11, Figura 12, Figura 13).36 Em vez disso, trata-se de uma técnica de pull-through na qual o seio urogenital é mobilizado até que a confluência atinja o períneo, onde a uretra e a vagina são separadas e anastomosadas ao períneo. Peña propôs que essa técnica reduziria a fístula uretrovaginal e a desvascularização do trato urinário. Como o trato urinário não pode ser mobilizado tão extensamente quanto a vagina, há limitações de até onde o canal comum pode ser mobilizado com essa técnica, sendo melhor utilizada em malformação cloacal com canal comum curto (< 3 cm). Uma vez que o reto é mobilizado do canal comum, o canal comum é dissecado circunferencialmente a partir do períneo e o canal comum é aberto até que a confluência da uretra e da vagina atinja a pele perineal sem tensão. O canal comum é fendido e utilizado para uma labioplastia. A uretra é anastomosada à borda anterior do introito, imediatamente posterior ao tecido clitoriano. A uretra e o introito vaginal são anastomosados à pele sem tensão. O corpo perineal é recriado e o reto é trazido à pele dentro do complexo muscular do esfíncter.

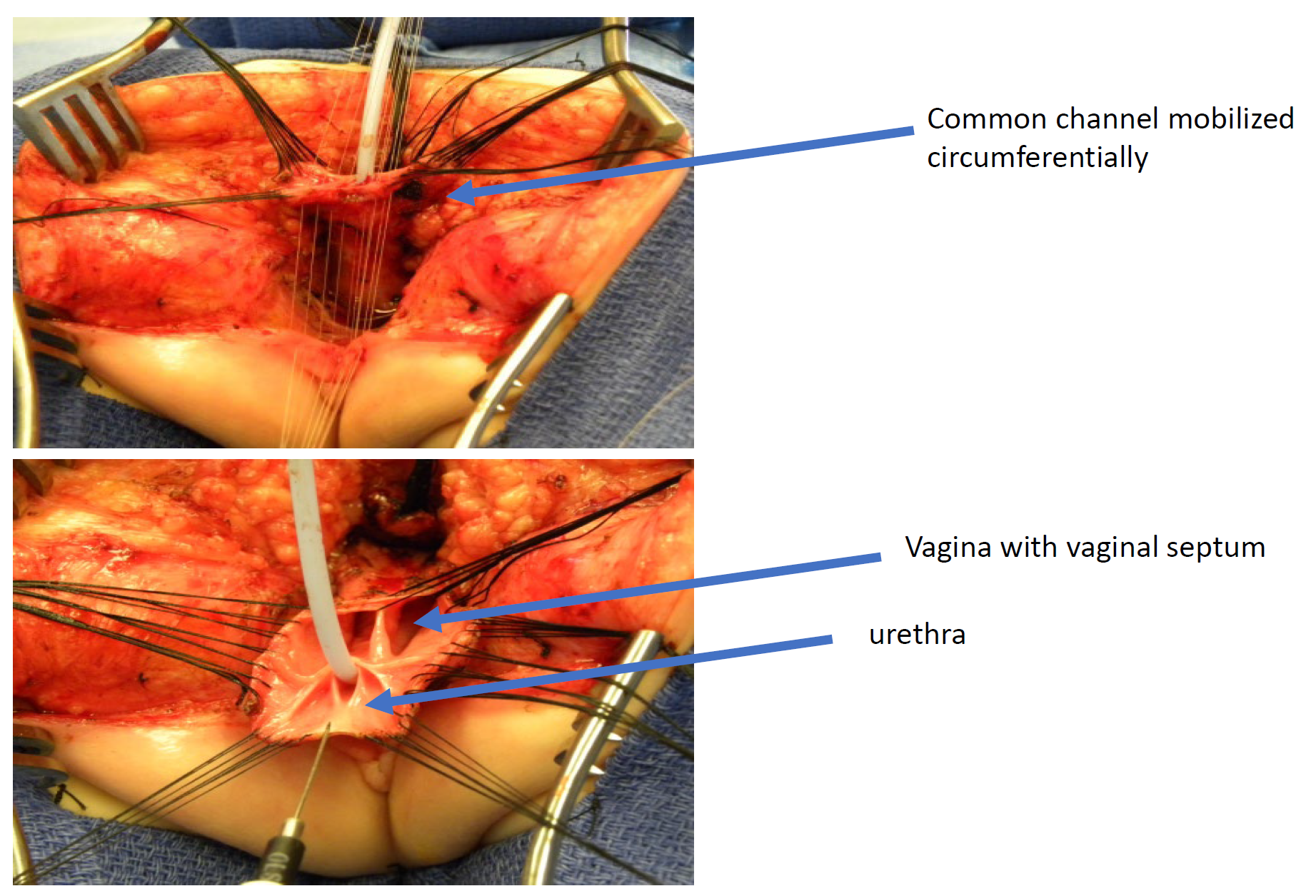

Figura 11 Fotografias intraoperatórias de um reparo cloacal com mobilização urogenital total (TUM). Foi realizada uma incisão sagital posterior, e o canal comum e as vaginas foram mobilizados conjuntamente em direção ao períneo. Nesta fotografia, o reto já foi separado.

Figura 12 Ilustração de uma correção cloacal por mobilização urogenital total (TUM). A mobilização está completa quando a confluência atinge o períneo e a uretra, a vagina e o reto podem ser anastomosados separadamente ao períneo. O canal comum é dividido, e o tecido redundante é rotacionado para revestir a abertura introital. (continua na Figura 13)

Figura 13 Ilustração de uma reconstrução cloacal por mobilização urogenital total (TUM). A mobilização está completa quando a confluência alcança o períneo e a uretra, a vagina e o reto podem ser anastomosados separadamente ao períneo. O canal comum é seccionado, e o tecido redundante é rotacionado para revestir a abertura introital. (continuação da Figura 12)

Determinando a Técnica Cirúrgica

Perspectiva histórica

A separação urogenital era a técnica principal para o reparo da cloaca e frequentemente requeria uma incisão sagital posterior juntamente com uma laparotomia. Essa técnica é tecnicamente exigente e demorada. Relatos iniciais de um cirurgião de alto volume descreveram resultados razoáveis, com 58,8% urinando espontaneamente, 28,4% realizando CIC e 2,8% com derivação urinária.35 Este estudo relata “controle urinário”, mas não fornece detalhes sobre acidentes urinários, esvaziamento ou função renal. A descrição por Peña da mobilização urogenital total introduziu uma abordagem mais simples para a malformação cloacal. Após um grande número de procedimentos TUM, ele relatou tempos operatórios mais curtos, menor tempo de internação e melhora da continência urinária (74%) e das evacuações voluntárias.37 Entretanto, ele relatou que, naquelas com cloaca e canais comuns longos (> 3 cm), havia alta complexidade na tomada de decisão intraoperatória e, frequentemente, após a mobilização completa do canal comum e quando este não alcançava, a vagina era então separada do canal comum mobilizado, deixando a uretra e o colo vesical mobilizados circunferencialmente, com vascularização comprometida e provável desnervação. Isso coloca a uretra em risco de desvascularização e necrose.

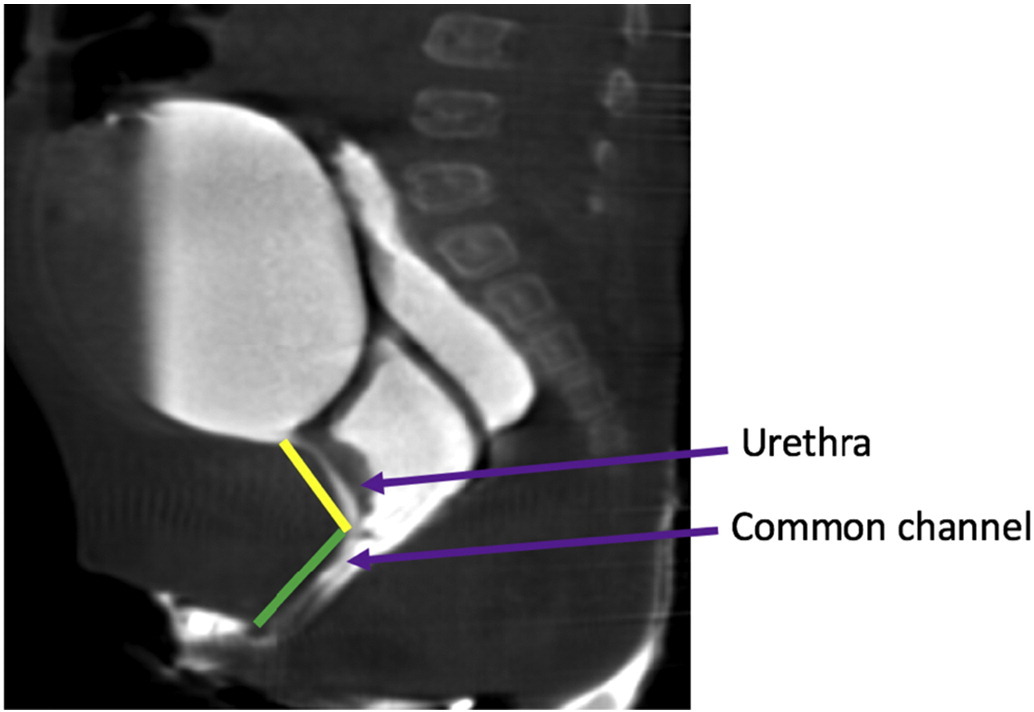

Essas duas experiências importantes no final da década de 1990 resultaram em um algoritmo cirúrgico baseado na medição do canal comum. Um canal comum curto (< 3 cm) seria melhor tratado com uma mobilização urogenital total, enquanto um canal comum longo (> 3 cm) teria recomendação de separação urogenital com ou sem laparotomia ou laparoscopia e enxerto de interposição intestinal se a vagina não atingisse a pele. Esse algoritmo depende muito de uma medição precisa do canal comum. A medição pode ser feita endoscopicamente sob visão direta, ou em cloacograma reconstruído bidimensional ou tridimensional (Figura 14). Entretanto, o cloacograma reconstruído tridimensional demonstrou ser a forma mais precisa de medir o canal comum e permite que cirurgiões menos experientes e profissionais em formação compreendam essa anatomia complexa no mesmo nível que cirurgiões seniores, aprimorando a preparação para o procedimento cirúrgico.38,39

Figura 14 Imagens de RM ponderadas em T2 no plano sagital da malformação cloacal, delineando a uretra e os comprimentos do canal comum.

Desenvolvimento do Algoritmo Cirúrgico Atual

Por quase 2 décadas, a tomada de decisão cirúrgica baseada apenas no comprimento do canal comum foi o padrão de cuidado. No entanto, à medida que a assistência multidisciplinar se tornou mais prevalente e os urologistas passaram a se envolver mais estreitamente no cuidado desses pacientes junto com a cirurgia pediátrica, observou-se que, embora a maioria das meninas com canais comuns curtos tivesse uretras mais longas, existe um subtipo incomum de meninas com canais comuns curtos que têm uretras muito curtas. Nesse subconjunto de pacientes, se fosse realizada uma TUM, isso resultaria em uma uretra muito curta e no colo vesical posicionado bem no períneo, com potencial de continência muito ruim. Como resultado dessa observação, foi desenvolvido um algoritmo atualizado incorporando tanto o comprimento do canal comum quanto o comprimento uretral na determinação da abordagem cirúrgica Figura 15.13 Nesse algoritmo, se um canal comum é > 3 cm, independentemente do comprimento uretral, realiza-se uma separação UG. Se um canal comum é < 3 cm e a uretra é > 1.5 cm, então a TUM é a abordagem operatória de escolha. Na variante incomum que apresenta um canal comum < 3 cm e uma uretra < 1.5 cm, este novo algoritmo determinaria que a criança deve ser submetida a uma separação UG, mantendo, assim, a posição anatômica da bexiga e do colo vesical dentro da pelve e evitando mobilizá-los para baixo e sob o diafragma pélvico. Este algoritmo cirúrgico representou a primeira vez em mais de 20 anos, desde a descrição da TUM por Peña, que uma nova técnica cirúrgica foi proposta, e tem sido bem aceito em centros de alto volume. Os resultados desse algoritmo têm sido excelentes no que diz respeito à redução da complexidade da tomada de decisão e de mudanças de plano intraoperatórias. Com uma avaliação pré-operatória precisa das medidas da uretra e do canal comum, pode-se evitar comorbidades urológicas significativas e obter uma uretra pérvia e cateterizável em 97% dos pacientes.40

Figura 15 Algoritmo cirúrgico sugerido para malformação cloacal.13

Manejo pós-operatório

O manejo da ferida e a drenagem por cateter são fundamentais após o reparo cloacal sagital posterior. Não há consenso quanto à duração da cateterização uretral após o reparo cloacal, mas isso geralmente varia de 1–2 semanas na TUM e até 4 semanas na separação UG. Alguns defendem a drenagem da bexiga por vesicostomia, mas isso não é necessário. As incisões sagital posterior e introital estão sob risco de deiscência, portanto evitar qualquer posição montada ou espargata é fundamental durante a cicatrização. Também se recomenda evitar pressão perineal, e que as crianças não sejam seguradas pelo períneo nem permaneçam sentadas em jumpers ou brinquedos de montaria. A anatomia pós-operatória é comumente avaliada com um exame clínico minucioso ou por cistoscopia e exame sob anestesia na sala de cirurgia.

Manejo vesical no pós-operatório

Após a correção cirúrgica da malformação cloacal, é importante assegurar esvaziamento vesical adequado. A mobilização cirúrgica e a disfunção vesical subjacente podem levar à retenção urinária ou a esvaziamento incompleto. Isso pode ser manejado fazendo com que todas as crianças realizem cateterismo intermitente após a retirada do cateter e ajustem o esquema de cateterismo com base nos volumes urinários. Outros utilizam avaliação urodinâmica pré-operatória para auxiliar na tomada de decisão sobre CIC. Não há consenso sobre o manejo vesical pós-operatório com cateterismo. Em um relato recente de 18 meninas submetidas à correção cloacal, 44.4% necessitaram de esvaziamento vesical assistido (CIC ou vesicostomia), enquanto as demais permaneceram com fraldas.41 Fatores associados à necessidade de CIC após a correção foram o comprimento longo do canal comum, separação UG e necessidade de esvaziamento vesical assistido antes da correção cirúrgica. Importante, o manejo com fraldas no pré-operatório não garantiu que o esvaziamento vesical assistido pudesse ser evitado no pós-operatório.

Manejo vaginal no pós-operatório

A patência pós-operatória do intróito vaginal é comumente avaliada com um exame minucioso em consultório ou exame sob anestesia. Se o intróito vaginal se tornar estenótico precocemente na infância, isso pode ser observado até que ela esteja mais velha e inicie a puberdade. Se a estenose for suficientemente grave para impedir o escoamento da menstruação, isso deve ser manejado antes da menarca. Recomenda-se vigilância ultrassonográfica do trato reprodutivo iniciando 6–9 meses após o desenvolvimento do botão mamário e prosseguindo a cada 6–9 meses até a menarca, avaliando a espessura endometrial em cada corpo uterino.15 Se for detectado fluxo menstrual obstruído, deve-se consultar ginecologia ou endocrinologia para iniciar supressão hormonal a fim de temporizar até a intervenção cirúrgica. As técnicas operatórias preferidas para estenose do intróito ou vaginal incluem introitoplastia simples ou vaginoplastia com mucosa bucal.42 Muitos centros têm especialistas em ginecologia pediátrica e do adolescente que monitoram isso, embora urologistas possam assumir esse cuidado onde ginecologistas pediátricos não estejam disponíveis.

Desfechos a Longo Prazo

Função vesical

A continência urinária é difícil de avaliar devido à complexidade e heterogeneidade da população. Hendren relatou ~60% de micção espontânea com “controle urinário” e Peña, de forma semelhante, relatou 54% de continência e 46% necessitando de cateterismo intermitente limpo (CIC). No entanto, nenhum desses estudos apresenta definições de continência nem relata taxas de reconstrução vesical.35,36 Mais recentemente, houve uma revisão dos desfechos de longo prazo para 50 pacientes com mais de 3 anos de idade com malformação cloacal reparada. Esse grupo relata 80% das meninas alcançando “continência social”, das quais 22% urinam espontaneamente enquanto o restante realiza CIC.43 Esse mesmo grupo teve 46% que necessitaram de um número médio de 4.7 procedimentos cirúrgicos para alcançar continência. Novamente, a definição de continência não está bem definida e muitas das que são “socialmente continentes” passaram por cirurgia reconstrutiva. Há grande necessidade de seguimento em longo prazo nessa população para determinar fatores associados à obtenção de continência e taxas de continência confiáveis.

Função Renal

Insuficiência renal é uma preocupação constante em meninas com malformação cloacal. A maior série de 64 pacientes relata que mais de 50% apresentam TFG < 80 mL/min/1.73 m2 com 17% apresentando doença renal terminal, 6% necessitando de transplante e 6% falecidas por insuficiência renal.44 Esse mesmo grupo enfatiza que a disfunção renal parece ser adquirida ao longo do tempo, pois 66% das meninas que progrediram para insuficiência renal crônica tinham nadir de creatinina sérica normal. Outras séries menores relatam resultados muito mais favoráveis, variando de 66–100% de meninas com função renal normal em 5–9 anos de seguimento.45,46,47 Curiosamente, essas séries são mais recentes e são todas de instituições com equipes multidisciplinares cuidando dessas meninas. Novamente, é muito necessário seguimento de longo prazo de centros de alto volume avaliando a função renal nessas pacientes.

Pontos-chave

- A malformação cloacal representa a forma mais grave de malformação anorretal feminina

- Comorbidades urológicas e sistêmicas são comuns, incluindo anomalias do trato urinário superior, anomalias müllerianas e disfunção vesical. A avaliação urológica abrangente e o cuidado multidisciplinar são fundamentais.

- O manejo inicial prioriza a drenagem precoce do hidrocolpos e a colostomia derivativa

- A cirurgia para reparar a malformação cloacal é chamada de anorretovaginorretoplastia sagital posterior (PSARVUP). Existem duas abordagens cirúrgicas principais: mobilização urogenital total (para malformações menos graves) e separação urogenital (para anomalias mais graves)

- Muitas meninas necessitarão de cateterismo vesical. Faltam dados de longo prazo sobre desfechos de continência e função renal

Leituras sugeridas

- Levitt MA, Peña A. Pitfalls in the management of newborn cloacas. Pediatr Surg Int 2005; 21: 264–269. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-005-1380-2.

- Harris KT, Kong L, Vargas M, Hou V, Pyrzanowski JL, Desanto K, et al.. Considerations and outcomes for adolescents and young adults with cloacal anomalies: a scoping review of urologic, colorectal, gynecologic and psychosocial concerns. Urology 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2023.08.047.

Referências

- AbouZeid AA, Mohammad SA, Shokry SS, El-Naggar O. Posterior cloaca: A urogenital rather than anorectal anomaly. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (3): 410.e1–410.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.01.014.

- Peña A, Bischoff A, Breech L, Louden E, Levitt MA. Posterior cloaca–further experience and guidelines for the treatment of an unusual anorectal malformation. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45 (6): 1234–1240. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.02.095.

- Thomas DFM. The embryology of persistent cloaca and urogenital sinus malformations. Asian J Androl 2019; 22 (2): 124. DOI: 10.4103/aja.aja_72_19.

- Falcone RA, Levitt MA, Peña A, Bates M. Increased heritability of certain types of anorectal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2007; 42 (1): 124–128. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.012.

- Skerritt C, DaJusta DG, Fuchs ME, Pohl H, Gomez-Lobo V, Hewitt G. Long-term urologic and gynecologic follow-up and the importance of collaboration for patients with anorectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg 2020; 29 (6): 150987. DOI: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2020.150987.

- Fuchs ME, Halleran DR, Bourgeois T, Sebastião Y, Weaver L, Farrell N, et al.. Correlation of anorectal malformation complexity and associated urologic abnormalities. J Pediatr Surg 2021; 56 (11): 1988–1992. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.02.051.

- Vilanova-Sanchez A, Halleran DR, Reck-Burneo CA. Re: A Descriptive Model for a Multidisciplinary Unit for Colorectal and Pelvic Malformations. J Urol 2019; 203 (4): 651–651. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000000723.04.

- Warne SA, Wilcox DT, Creighton S, Ransley PG. Long-Term Gynecological Outcome of Patients with Persistent Cloaca. J Urol 2003; 170 (4 Part 2): 1493–1496. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000086702.87930.c2.

- Mosiello GIOVANNI, Capitanucci MARIALUISA, Gatti CLAUDIA, Adorisio OTTAVIO, Lucchetti MARIACHIARA, Silveri MASSIMILIANO, et al.. How to Investigate Neurovesical Dysfunction in Children With Anorectal Malformations. J Urol 2003; 170 (4 Part 2): 1610–1613. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000083883.16836.91.

- Goossens WJH, Blaauw I de, Wijnen MH, Gier RPE de, Kortmann B, Feitz WFJ. Urological anomalies in anorectal malformations in The Netherlands: effects of screening all patients on long-term outcome. Pediatr Surg Int 2011; 27 (10): 1091–1097. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-011-2959-4.

- Jindal B, Grover V, Bhatnagar V. The Assessment of Lower Urinary Tract Function in Children with Anorectal Malformations before and after PSARP. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2009; 19 (01): 34–37. DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1039027.

- Warne STEPHANIEA, Godley MARGARETL, Wilcox DUNCANT. Surgical Reconstruction Of Cloacal Malformation Can Alter Bladder Function: A Comparative Study With Anorectal Anomalies. J Urol 2004; 172 (6 Part 1): 2377–2381. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145201.94571.67.

- Davies MRQ. Anatomy of the nerve supply of the rectum, bladder, and internal genitalia in anorectal dysgenesis in the male. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32 (4): 536–541. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90702-8.

- Cardamone S, Creighton S. A gynaecologic perspective on cloacal malformations. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2015; 27 (5): 345–352. DOI: 10.1097/gco.0000000000000205.

- Breech L. Gynecologic concerns in patients with anorectal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg 2010; 19 (2): 139–145. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.11.019.

- Breech L. Gynecologic concerns in patients with cloacal anomaly. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016; 25 (2): 90–95. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.11.006.

- Levitt MA, Patel M, Rodriguez G, Gaylin DS, Pena A. Tethered Spinal Cord in Patients with Anorectal Malformations. Anorectal Malformations in Children 1997; 2 (3): 281–286. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-540-31751-7_18.

- Kim SM, Chang HK, Lee MJ. Re: Spinal Dysraphism With Anorectal Malformation: Lumbosacral Magnetic Resonance Imaging Evaluation of 120 Patients. J Urol 2010; 185 (3): 1094–1094. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(11)60163-8.

- Beaufort CMC de, Groenveld JC, Mackay TM, Slot KM, Beer SA de, Jong JR de, et al.. Spinal cord anomalies in children with anorectal malformations: a retrospective cohort study. Pediatr Surg Int 2023; 39 (1): 281–286. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-023-05440-y.

- Muller CO, Crétolle C, Blanc T, Alova I, Jais J-P, Lortat-Jacob S, et al.. Impact of spinal dysraphism on urinary and faecal prognosis in 25 cases of cloacal malformation. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (6): 1199–1205. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.05.012.

- Garvey EM, Fuller M, Frischer J, Calkins CM, Rentea RM, Ralls M, et al.. Multi-Institutional Review From the Pediatric Colorectal and Pelvic Learning Consortium of Minor Spinal Cord Dysraphism in the Setting of Anorectal Malformations: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. J Pediatr Surg 2023; 58 (8): 1582–1587. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2023.04.009.

- Inserm. VACTERL/VATER association. Definitions 2011; 6 (56). DOI: 10.32388/m8pjt5.

- Levitt MA, Peña A. Anorectal malformations. Pediatr Surg Int 2007; 3-3 (2-3). DOI: 10.1007/bf00182758.

- Jacobs SE, Tiusaba L, Al-Shamaileh T, Bokova E, Russell TL, Ho CP, et al.. Fetal and Newborn Management of Cloacal Malformations. Children (Basel) 2022; 9 (6): 888. DOI: 10.3390/children9060888.

- Dannull KA, Browne LP, Meyers MZ. The spectrum of cloacal malformations: how to differentiate each entity prenatally with fetal MRI. Pediatr Radiol 2019; 49 (3): 387–398. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-018-4302-x.

- Bischoff A, Trecartin A, Alaniz V, Hecht S, Wilcox DT, Peña A. A cloacal anomaly is not a disorder of sex development. Pediatr Surg Int 2019; 35 (9): 985–987. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-019-04511-3.

- Vilanova-Sanchez A, Reck CA, Sebastião YV, Fuchs M, Halleran DR, Weaver L, et al.. Can sacral development as a marker for caudal regression help identify associated urologic anomalies in patients with anorectal malformation? J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53 (11): 2178–2182. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.03.018.

- VanderBrink BA, Reddy PP. Early urologic considerations in patients with persistent cloaca. Semin Pediatr Surg 2016; 25 (2): 82–89. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2015.11.005.

- Rink RC, Adams MC, Misseri R. A New Classification for Genital Ambiguity and Urogenital Sinus Anomalies. J Urol 2005; 175 (4): 1500–1501. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)00847-5.

- Wood RJ, Reck-Burneo CA, Dajusta D. Re: Cloaca Reconstruction: A New Algorithm Which Considers the Role of Urethral Length in Determining Surgical Planning. J Urol 2018; 204 (6): 1368–1368. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001276.02.

- Patel MN, Racadio JM, Levitt MA, Bischoff A, Racadio JM, Peña A. Complex cloacal malformations: use of rotational fluoroscopy and 3-D reconstruction in diagnosis and surgical planning. Pediatr Radiol 2012; 42 (3): 355–363. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-011-2282-1.

- Halleran DR, Smith CA, Fuller MK, Durhm MM, Dickie B, Avansino JR, et al.. Measure twice and cut once: Comparing endoscopy and 3D cloacagram for the common channel and urethral measurements in patients with cloacal malformations. J Pediatr Surg 2020; 55 (2): 257–260. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.10.045.

- Chalmers DJ, Rove KO, Wiedel CA, Tong S, Siparsky GL, Wilcox DT. Clean intermittent catheterization as an initial management strategy provides for adequate preservation of renal function in newborns with persistent cloaca. J Pediatr Urol 2015; 11 (4): 211.e1–211.e4. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.05.014.

- Versteegh HP, Sutcliffe JR, Sloots CEJ, Wijnen RMH, Blaauw I de. Postoperative complications after reconstructive surgery for cloacal malformations: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19 (4): 201–207. DOI: 10.1007/s10151-015-1265-x.

- Hendren WH. Cloaca, The Most Severe Degree of Imperforate Anus. Ann Surg 1998; 228 (3): 331–346. DOI: 10.1097/00000658-199809000-00006.

- Peña A. Total urogenital mobilization–An easier way to repair cloacas. J Pediatr Surg 1997; 32 (2): 263–268. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(97)90191-3.

- Levitt MA, Peña A. Cloacal malformations: lessons learned from 490 cases. Semin Pediatr Surg 2010; 19 (2): 128–138. DOI: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2009.11.012.

- Reck-Burneo CA, Lane V, Bates DG. Re: The Use of Rotational Fluoroscopy and 3-D Reconstruction in the Diagnosis and Surgical Planning for Complex Cloacal Malformations. J Urol 2019; 204 (6): 1367–1368. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001276.01.

- Gasior AC, Reck C, Lane V, Wood RJ, Patterson J, Strouse R, et al.. Transcending Dimensions: a Comparative Analysis of Cloaca Imaging in Advancing the Surgeon’s Understanding of Complex Anatomy. J Digit Imaging 2019; 32 (5): 761–765. DOI: 10.1007/s10278-018-0139-y.

- Skerritt C, Wood RJ, Jayanthi VR, Levitt MA, Ching CB, DaJusta DG, et al.. Does a standardized operative approach in cloacal reconstruction allow for preservation of a patent urethra? J Pediatr Surg 2021; 56 (12): 2295–2298. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2021.01.011.

- Davis M, Mohan S, Russell T, Feng C, Badillo A, Levitt M, et al.. A prospective cohort study of assisted bladder emptying following primary cloacal repair: The Children’s National experience. J Pediatr Urol 2023; 19 (4): 371.e1–371.e11. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2023.03.017.

- Leeuwen K van, Baker L, Grimsby G. Autologous buccal mucosa graft for primary and secondary reconstruction of vaginal anomalies. Semin Pediatr Surg 2019; 28 (5): 150843. DOI: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2019.150843.

- Warne SA, Wilcox DT, Ransley PG. Long-term Urological Outcome of Patients Presenting with Persistent Cloaca. J Urol 2002; 168(4: 1859–1862. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210020-00048.

- Warne SA, Wilcox DT, Ledermann SE, Ransley PG. Renal Outcome in Patients With Cloaca. J Urol 2002; 67 (6): 2548–2551. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200206000-00055.

- Braga LHP, Lorenzo AJ, Dave S, Del-Valle MH, Khoury AE, Pippi-Salle JL. Long-term renal function and continence status in patients with. Can Urol Assoc J 2007; 1 (4): 371. DOI: 10.5489/cuaj.442.

- DeFoor WR, Bischoff A, Reddy P, VanderBrink B, Minevich E, Schulte M, et al.. Chronic Kidney Disease Stage Progression in Patients Undergoing Repair of Persistent Cloaca. J Urol 2015; 194 (1): 190–194. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.01.080.

- Rink RC, Herndon CDA, Cain MP, Kaefer M, Dussinger AM, King SJ, et al.. Upper and lower urinary tract outcome after surgical repair of cloacal malformations: a three-decade experience. BJU Int 2005; 96 (1): 131–134. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2005.05581.x.

- Levitt MA, Peña A. Pitfalls in the management of newborn cloacas. Pediatr Surg Int 2005; 21: 264–269. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-005-1380-2.

- Harris KT, Kong L, Vargas M, Hou V, Pyrzanowski JL, Desanto K, et al.. Considerations and outcomes for adolescents and young adults with cloacal anomalies: a scoping review of urologic, colorectal, gynecologic and psychosocial concerns. Urology 2023. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2023.08.047.

Ultima atualização: 2025-09-21 13:35