28: Undescended Testis

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 17 minutos para ler.

Introduction

Undescended testis (UDT) refers to the state that the testicle is not located in the scrotum but in an abnormal location such as in the abdominal cavity of the groin (Figure 1) The testicles are formed and remain in the abdominal cavity for a while during fetal life, then gradually descend and move down to the scrotum. Cryptorchidism includes undescended testes located anywhere in the normal course of the descending process and ectopic testes which is not the usual course of testicular descendant. Undescended testis should be differentiated from retractile testis. A retractile testis is a testicle locates below the external inguinal ring but can be manipulated to the upper scrotum and is prone to ascend to its original position and/or is a testicle that has finished its normal descending process and can remain in the scrotum but easily move back and forth between the scrotum and the groin (Video 1).

Figure 1 Empty scrotum on the left side in a patient with undescended testis.

Video 1 Demonstration of a retractile testis.

Epidemiology

Undescended testis is one of the most common congenital anomalies of the male newborn child. The risk of undescended testes is 3.5 fold higher in males with a sibling with undescended testes, and 2.3 fold higher in males with a father with the condition.1 Incidence in the full-term neonates is reported to be 1.0–4.5% and unilateral cases are 2 times more common than bilateral cases.2 About 70% of cryptorchids descend at 3 mo of age under influence of mini puberty and the incidence of undescended testis decreases to 0.8-1.2% at 1 year of age.3,4

Etiology

There is no clear risk factors associated to (UDT), however maternal smoking during pregnancy, birth measures including birth weight, and gestational age, family history of undescended testis, and rare genetic variants such as INSL3 mutations are been associated with undescended testis Normal testicular descent relies on an intact hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Although the exact etiology is still unknown, its genetic, hormonal (HPG axis dysfunction, congenital hypogonadism, testicular dysplasia), and anatomical (short vas deferens and spermatic vessels) factors are implicated. Birth weight <2.5 kg, small for gestational age, premature, low maternal estrogen levels and placental insufficiency, reduced human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) secretion were suggested as risk factors for undescended testis. In addition, exposure to environmental factors such as continuous exposure to organochlorine compounds, monoesters of phthalates, maternal smoking, maternal diabetes has been reported as risk factor for developmental disorders in men. However, none of these factors was found to be solely responsible for the pathogenesis of undescended testis.

Normal Testicular Descent

Mammals can be separated into those with a scrotum and those without. The general hypothesis for the evolution of the scrotum in some mammals is that it provides a cool environment, which is below the core body temperature for better spermatogenesis. However, we have no data to support or reject the temperature hypothesis because some mammals can reproduce with their internal testicles and some ascrotal species have their testicular cooling mechanisms.5,6 Reduced rate of germ-cell mutations at lower body temperatures may have been a driving factor of development of scrotum in mammals. Some animals with testes stay close to the kidney in the abdominal cavity extend their epididymis to a subcutaneous location, which may provide a cooling effect during sperm storage and maturation.7 In that case, testicular locations might have followed the location of the epididymis. In humans, the scrotal temperature is maintained at an optimal temperature for spermatogenesis about 2.7 ℃ lower than the core body temperature.8

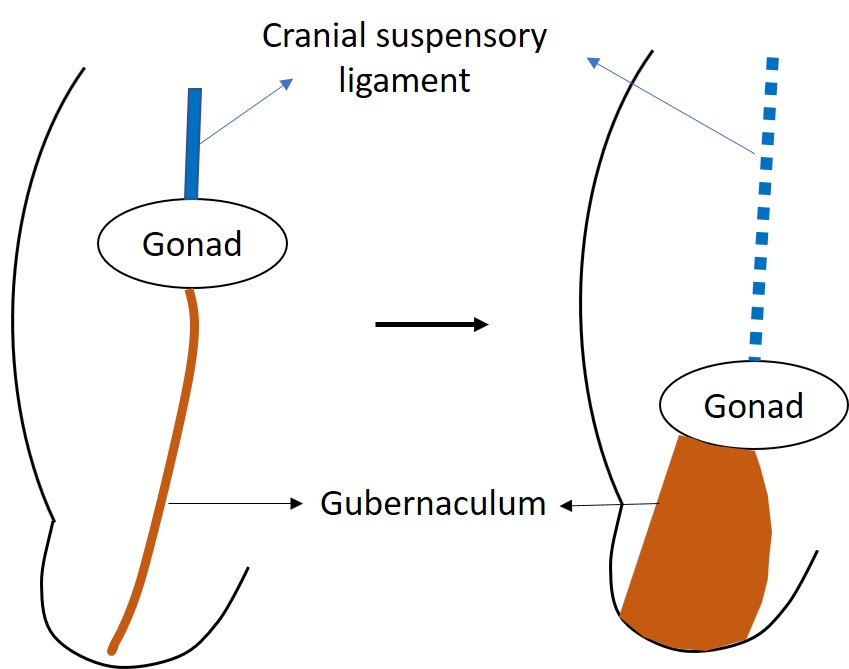

Although the testes and ovaries originate from the same embryological tissues adjacent to the kidney, testes take the long journey out of the abdominal cavity.9 Normal testicular descent involves a transabdominal phase and an inguinoscrotal phase and both of which take place prenatally in the human. Transabdominal descent occurs in the 12th week of gestation when the testis moves down towards the deep inguinal ring. It occurs as a combination of push and pull interchange.10 Before the start of the descent, the developing gonad is anchored by the cranial suspensory ligament and the caudal genito-inguinal ligament, or gubernaculum.11 The distal gubernaculum enlarges during the transabdominal phase of the descent making the male gubernaculum short and fat. This swelling reaction anchors the testis to the inguinal canal (Figure 2) The inguinal wall muscles differentiate around the swollen gubernaculum, also called the bulb, to make the inguinal canal. Insulin-like hormone 3 (INSL3) is known to be the regulating hormone of the swelling reaction.12,13,14 Leydig cells of the testis secrete INSL3 to stimulate the swelling reaction and it keep the testis close to the inguinal abdominal wall as the fetal abdomen enlarges.14 Anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) secreted from the Sertoli cells of the testis is also suggested to have a role in testicular descent. In children with mutations of the AMH gene or its receptor, they have cryptorchidism with persisting infantile uterus and fallopian tubes, known as the persistent müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS).14

Figure 2 The undifferentiated gonad is initially located high in the abdomen, anchored by the cranial suspensory ligament. INSL3 causes the swelling and enlargement of the gubernaculum to pull the developing testis toward the inguinal region.

The inguinoscrotal phase of descent occurs between 25 and 35 weeks. The overall process is quite similar in most mammals.15 During this stage the testes transit through the inguinal canal to finally reside in the scrotum. The gubernaculum elongates towards the scrotum along with the processus vaginalis. After the gubernaculum reaches the scrotum, the bulb resorbs to leave a fibrous remnant adherent to the inside of the scrotum. The proximal processus vaginalis closes to prevent inguinal hernia or hydrocele in the human. Many other mammals such as mice and rats have a patent processus vaginalis for their lifetime. In the human, the processus vaginalis finally involutes completely and enables the spermatic cord to elongate normally after birth. The inguinoscrotal phase of testicular descent is under the control of androgens. In animal models, it was found that, depending on the androgen action, the sensory branches of the genitofemoral nerve control gubernacular development which is modulated by calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).

Classification of Undescended Testes

In general, undescended testes are classified as palpable or non-palpable testes. Whether the testes are palpable or not decides the diagnostic tests and treatment strategy, and also the prognosis. Testes are movable by the contraction of the cremasteric muscle. Therefore the exact location of the testes is to be measured before 6 months of age when the cremasteric reflex is weak, or under general anesthesia. About 80% of undescended testes are palpable around the inguinal area. In case the testis is not palpable, it may locate in the abdominal cavity or agenesis, atrophic or vanishing testes.

Associated Pathology

Abnormal Germ Cell Development

The histologic development of prepubertal cryptorchid testes has been studied in many observational types of research. These studies provide strong evidence that abnormal germ cell development is often present after early infancy in cryptorchid testes. The number of spermatogonia per tubule is reduced after infancy and fails to increase normally with age in cryptorchid and contralateral scrotal testes to a lesser degree.16 Transformation of gonocytes to spermatogonia is reported to be impaired in cryptorchid testes. The ratio of gonocytes to spermatogonia appears to be normal in cryptorchid testes at about 1.5 months of age, delayed disappearance of gonocytes, and appearance of adult dark spermatogonia occurs in the cryptorchid testes compared with the contralateral scrotal testes. It was reported that the cryptorchid testis is not significantly smaller at birth but grows less well than the scrotal testis.17

Infertility

A history of cryptorchidism is well known to be associated with subfertility. In a series of well-designed case-control studies of fertility in cryptorchidism which analyzed a large cohort of men who underwent orchiopexy and control group of similar age, 65% of former bilateral, 90% of former unilateral, and 93% of controls were successfully achieved paternity.18,19 According to the studies reporting testicular histology at the time of orchiopexy, fertility potential was greatest when orchiopexy was performed before 1 year of age.20,21,22 Therefore, orchiopexy is recommended to be performed before 1 year of age.

Risk of Malignancy

The risk of testicular germ cell tumor in males with a history of cryptorchidism has been well known to be increased. The relative risk of malignant transformation in an undescended testis is 2.5 to 8 overall and 2 to 3 in boys undergoing prepubertal orchiopexy.23 About 10% of men presenting testicular germ cell tumor are men with a history of cryptorchidism. In a review of tumor pathology in treated versus untreated cryptorchidism, seminoma is most commonly associated with persistently cryptorchid testis and non-seminomatous germ cell tumor is the majority of scrotal testes.23 Today this as been showed that is not related testicular self-examination is recommended for testicular cancer screening, and it should be taught to all patients with a history of cryptorchidism after they reach puberty.

Hernia

More than 90% of cryptorchism accompanies patent processus vaginalis and the hernia can occur in 25%.

Epididymis Abnormality

The prevalence of epididymal anomalies in cryptorchidism is reported to be 32% to 72%.24 Epididymal anomalies may occur due to abnormal involution of the mesonephric duct adjacent to the normal testis.25 Epididymal-testicular fusion anomalies are reported to be strongly associated with a more proximal position of the testis. Epididymal anomalies may result in impaired fertility due to difficulties in sperm transportation and maturation.26

Diagnosis of Undescended Testis

Before the physical examination, it is essential to ask about early delivery, whether the mother is using female hormones or exposure to female hormones, central nervous system lesions, and previous groin surgery history. A family history of other congenital anomalies or infertility accompanying cryptorchidism should be checked. Because the palpability of cryptorchidism is more important than the location of the testes, a careful physical examination is essential. In case of doubt, it is recommended to repeat the examination or refer to a specialist. In particular, in case of non-palpable, it is important to check under anesthesia before surgery. For the physical examination method the room need to be warm. Then, with the patient in the frog-legged position, first check the size, location, and surface of the contralateral testis, and then with a warm hand, sweep from the iliac crest on the affected side to the pubic symphysis to determine the presence and location of the testicle. If the testicle is palpable, it should also be checked that it descends to the scrotum.27 If it is difficult to palpate, such as a chubby infant or an obese child, have them sit with their legs crossed or squat to examine them and apply lubricating jelly to their hands for better palpation of the testicles. In the absence of one testis, compensatory hypertrophy of the contralateral testis may be seen. Once the testicles are palpable, there is no need for further examination, because the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not as high as that of expert urologists, and the treatment is rarely different depending on the results of imaging tests. Imaging studies cannot certainly verify whether a testis is present or not.28 In clinical practice, ultrasound or MRI is only recommended in selected cases with suspicious DSD patients.29

For non-palpable testicles that cannot be confirmed by physical examination and radiology examination, a diagnostic laparoscopy or exploratory surgery through the inguinal or scrotal incision is performed. Conventionally, if a testicle or testicular nubbin were found through inguinal exploration, orchiopexy or orchiectomy was followed. With the advent of laparoscopy, it has become possible to check the presence or absence of testes, their location, and the state of the vas deferens and gonad vessels. On laparoscopic findings, if the testicular vessels end blindly, it can be diagnosed as vanishing testis and no further management is necessary. If spermatic vessels are observed to enter into the internal inguinal ring, inguinal or scrotal exploration should be followed.

In case of bilateral non-palpable testes with any sign of DSD, such as genital ambiguity, or severe hypospadias, further endocrinological and genetic assessment is mandatory.30 In children under 3 months of age, luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and testosterone are measured. In children aged 3 months or older, human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) stimulation test is recommended. If testosterone is barely measured and LH and FSH are elevated, it can be assessed as an anorchidism. In the hCG stimulation test, after intramuscular injection of 2,000 IU of hCG for 3 days, serum testosterone is measured on the 5th day. However, since there is a possibility of a false negative, surgical confirmation is necessary for all children whose gonadotropin levels are within the normal range without palpation of both testicles regardless of whether they respond to the hCG stimulation test.

Treatment of Undescended Testis

The goal of treatment for undescended testicles is to lower the risk of infertility by minimizing the histological degeneration of the testicles by placing the testicles into the scrotum at an early stage and to make it easier to detect testicular cancer, which has a higher incidence than normally descended one. In addition, the secondary goal is to correct the accompanying lesions, prevent complications such as testicular torsion, alleviate the psychological impact of the patient, and improve the cosmesis. Until now, it has been recognized that orchiopexy cannot prevent testicular cancer, but recently, it has been reported that early surgery can lower the risk of testicular cancer. The timing of treatment for undescended testicles is important. Orchiopexy should be performed after 6 months of age and within the subsequent year, and by age eighteen months at the latest.31 The rationale for such early surgery is that natural descent of the testicles after 6 months of age is unlikely, there is no significant difference in risks of general anesthesia or surgical technique, and the possibility of histological damage to the testicles increases after this age.31,32 And there are also concerns for children over 18 months of age that might have high separation anxiety and fear of castration due to surgery, which may impact the children’s mental health.

Surgical treatment, orchiopexy, is the standard treatment for undescended testicles, and hormone therapy can be selectively used depending on the location and condition of the undescended testicles. When testicles degenerate or disappear and only remnants or nubbin of testicles are visible, or when adult undescended testes are anatomically and morphologically abnormal, or when testicular fixation is impossible, the testicles are excised. Orchiectomy should be carefully decided only when the contralateral testicle is normal, and the contralateral orchiopexy is performed simultaneously to prevent testicular torsion. Since the retractile testis is a normal variant, it is recommended to follow up annually until puberty or until the testes no longer migrate upward.

Hormonal Therapy for Testicular Descent

Hormonal therapy for testicular decent is a debatable issue. However, hCG, luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists or gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists are mainly used. The rationale for hormonal therapy is based on the experimental results that undescended testicles result from an abnormality in the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal axis, testicular descent is regulated by male androgens, and high concentrations of active metabolites synthesized in the testes are involved in the pathogenesis of cryptorchidism. hCG acts directly on Leydig cells like LH from the pituitary, whereas GnRH increases testosterone production in the testis by secreting LH through hypothalamic stimulation. It is presumed that the hormone affects the spermatic cord and the cremasteric muscle to induce the natural descent of the testicles and enhance fertility. However, the success rate of hormonal therapy using hCG or GnRH is only 20% and almost 20% of these descended testes may re-ascend later.33,34

Hormonal Therapy for Fertility

Hormonal therapy may improve fertility indices and can serve as an additional implementation to orchiopexy.35,36 It was reported that men who were treated with GnRH in childhood had better semen analysis compared with men who underwent orchiopexy alone or placebo treatment.35 On the contrary it is reported that hCG therapy may be harmful to future spermatogenesis by increased apoptosis of germ cells, inflammatory changes in the testes, and reduced testicular volume in adulthood.37 Evidence on the long-term effect of hormonal treatment for cryptorchidism is still lacking and it is difficult to select the best candidate with undescended testis who can benefit from hormonal therapy.

Surgical Treatment

Palpable Testis

In most cases of palpable undescended testes, orchiopexy is performed through an inguinal incision. The most important point in orchiopexy is to secure enough length to lower the testicle to the scrotum without tension. The operation consists of the following four steps. First, the testis and spermatic cord are separated from the surrounding tissues to secure mobility. Secondly, high- ligation is performed to close the process vaginalis. And thirdly, to lower the testicle to the bottom of the scrotum without tension, sometimes further retroperitoneal dissection is necessary to separate the vas deferens. Finally, a shallow sub-dartos pouch is made in the ipsilateral scrotum, and the testes are tucked in and fixed. If the length of the spermatic cord is not sufficient with these basic techniques, the Prentiss method is required to reduce the distance to the scrotum by cutting the inferior epigastric vessel at the bottom of the inguinal canal or passing the spermatic cord underneath it. Not typically for the palpable UDT, autotransplantation of the testis using a microsurgical technique to anastomose the testicular artery to the epigastric artery has been reported (see below).

Non-Palpable Testis

Since the presence and condition of the testes are important in the operation of non-palpable testicles, the testes should be examined again under anesthesia. If they are still not palpable, open inguinal exploration or diagnostic laparoscopy is performed. The laparoscopic findings of non-palpable testes are: first, the testicular vessel descends through the internal inguinal ring. In this case, an incision is made in the inguinal or scrotal skin to explore the presence of the testis. If the testicles are found to be normal, orchiopexy is performed. The second scenario is that the testicular vessel ends in a blind end in the abdominal cavity near the internal inguinal ring, which suggests a vanished testis, so the operation is stopped without further surgery. Finally, when a testicle is found in the abdominal cavity, the surgical decision is made based on the size of the testicle, its location in the abdominal cavity, the length of the spermatic vessel, the patient's age, the contralateral testis, and the surgeon's experience. The overall surgical success rate is known to be 67-84%.

Orchiopexy is Performed in One of Three Ways

Fowler-Stephens Orchiopexy

This is a procedure that secures the spermatic cord length by excising the internal spermatic blood vessel containing the testicular artery, and the survival of the testicle is dependent on the blood supply of the cremasteric artery and the vas deferens artery. The one-stage technique is a method of resection of internal spermatic vessels and fixation of the testicles at the same time. In the two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy, the internal spermatic vessels are ligated as the primary operation, and the supply of collateral blood vessels from the abdominal cavity to the testicles is increased for at least 6 months, and then the testes are lowered to the scrotum by a secondary operation. One stage or two-staged Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy may be performed laparoscopically.

Laparoscopic Orchiopexy

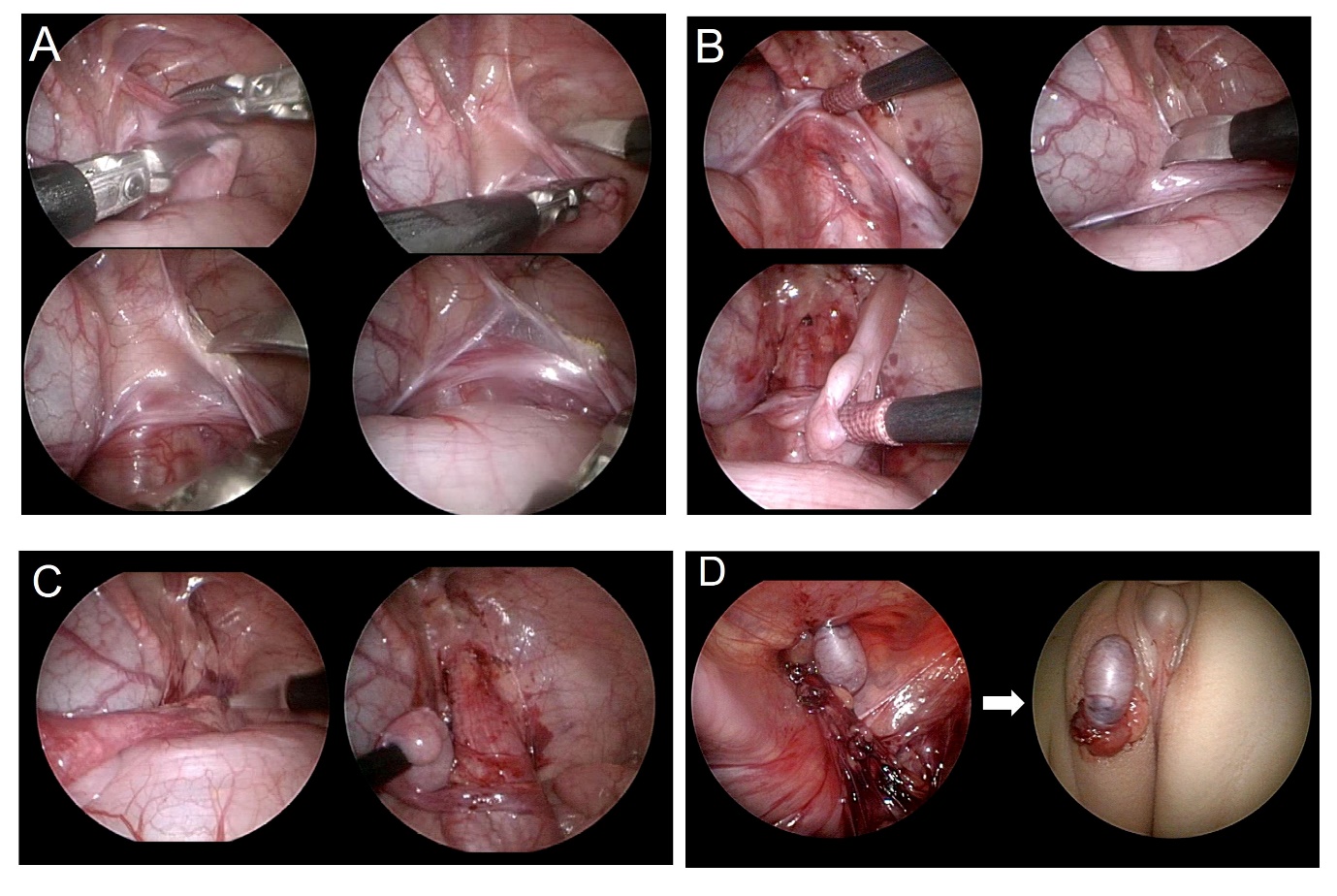

Since laparoscopic surgery is performed with an enlarged field of view, it has the advantage of being able to minimize damage to blood vessels while dissecting extensively, and to secure the shortest distance of testicular mobilization (Figure 3) and (Video 1). Laparoscopic orchiopexy includes a method in which the testicle is lowered to the scrotum while preserving the internal spermatic vessels and Fowler-Stephens methods (Video 2). With the help of laparoscopy, microsurgical autotransplantation can be performed.

Figure 3 Step by step explanatory images of the laparoscopic orchiopexy. (A) cutting the gubernaculum, (B) dissection of the peritoneum parallel to the vas deferens, (C) incision of the peritoneum parallel to the internal spermatic vessel, (D) neo-hiatus formation and delivery of the testis out of the abdomen to the scrotal location.

Video 2 Demonstration of Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy.

Autotransplantation Using Microsurgery

This is performed in special cases where the testes are located deep in the abdominal cavity. First, the testes and spermatic cords are excised, fixed in the scrotum, and then the testicular blood vessels are connected to the lower abdominal wall blood vessels through micro-surgery to re-open blood flow. Although the success rate is relatively high, it is not an easy method of choice because it requires a high level of skill and effort required for vascular connection through microsurgery and requires careful postoperative treatment.

Orchiectomy

Orchiectomy is performed when a testicular function cannot be expected due to severe testicular atrophy or morphological abnormalities.

Complications of Orchiopexy and Reoperation

Complications of orchiopexy include testicular retraction, hematoma, ilioinguinal nerve injury, torsion of the spermatic cord, injury to the vas deferens, or testicular atrophy. Testicular atrophy is the most serious complication and occurs after excessive dissection of the spermatic cord or excessive use of electrocautery, twisting of the spermatic vessels, or Fowler Stephens orchiopexy when the testis is forced down with tension, affecting the blood supply testicular retraction is usually caused by insufficient retroperitoneal dissection, and the testicle is pulled up above the scrotum under the external inguinal ring or near the pubic tubercle. For reoperation, care must be taken to avoid the previous surgical site and make an incision, approach the scar tissue from the normal tissue, and remove the hard scar tissue including normal tissue so that the spermatic vessels are not damaged, and then perform testicular fixation.

Key Points

- AUA guideline for cryptorchidism state surgery for UDT is best performed prior to 1 year of age

- The Choosing Wisely campaign in cooperation with the AUA chose to emphasize that imaging for UDT should not be routinely performed, as confirmation of testicular position is best done by exam or if needed in case of non-palpable testis, laparoscopy.

- Inguinal or scrotal orchiopexy has high rate of success with low complication rate

- Laparoscopic orchiopexy is associated with higher rates of testicular atrophy

References

- Hutson JM, Balic A, T N. Cryptorchidism. Semin Pediatr Surg 2010; 19: 215. DOI: 10.1002/bjs.1800760203.

- Ashley RA, JS B, Kolon TF. Cryptorchidism: pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Urol Clin North Am 2010; 37: 183. DOI: 10.1016/j.ucl.2010.03.002.

- Elder JS. The undescended testis. Hormonal and Surgical Management Surg Clin North Am 1988; 68: 983. DOI: 10.1515/iupac.88.1460.

- Sijstermans K, Hack WW, RW M. The frequency of undescended testis from birth to adulthood: a review. Int J Androl 2008; 31: 1. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2605.2008.00883.x.

- Werdelin L, Nilsonne A. The evolution of the scrotum and testicular descent in mammals: a phylogenetic view. J Theor Biol 1999; 196: 61. DOI: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0821.

- Lovegrove BG. Cool sperm. why some placental mammals have a scrotum. J Evol Biol 2014; 27: 801. DOI: 10.1111/jeb.12373.

- Bedford JM. Anatomical evidence for the epididymis as the prime mover in the evolution of the scrotum. Am J Anat 1978; 152: 483. DOI: 10.1002/aja.1001520404.

- Momen MN, Ananian FB, IM F. Effect of high environmental temperature on semen parameters among fertile men. Fertil Steril 2010; 93: 1884. DOI: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.12.065.

- Hutson JM, S H, Heyns CF. Anatomical and functional aspects of testicular descent and cryptorchidism. Endocr Rev 1997; 18: 259. DOI: 10.1210/er.18.2.259.

- Costa WS, Sampaio FJ, LA F. Testicular migration: remodeling of connective tissue and muscle cells in human gubernaculum testis. J Urol 2002; 167: 2171. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200205000-00065.

- P S, W E. Perinatal development of gubernacular cones in rats and rabbits: effect of exposure to anti-androgens. Anat Rec 1993; 236: 399. DOI: 10.1002/ar.1092360214.

- Nef S, Parada LF. Cryptorchidism in mice mutant for Insl3. Nat Genet 1999; 22: 295. DOI: 10.1038/10364.

- Zimmermann S, Steding G, JM E. Targeted disruption of the Insl3 gene causes bilateral cryptorchidism. Mol Endocrinol 1999; 13: 681. DOI: 10.1210/mend.13.5.0272.

- Hutson JM, Li R, BR S. Regulation of testicular descent. Pediatr Surg Int 2015; 31: 317. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-015-3673-4.

- Hutson JM, Baskin LS, G R. The power and perils of animal models with urogenital anomalies: handle with care. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10: 699. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.03.003.

- Gracia J, Sanchez Zalabardo J, J SG. Clinical, physical, sperm and hormonal data in 251 adults operated on for cryptorchidism in childhood. BJU Int 2000; 85: 1100. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00662.x.

- Kollin C, Hesser U, EM R. Testicular growth from birth to two years of age, and the effect of orchidopexy at age nine months: a randomized, controlled study. Acta Paediatr 2006; 95: 318. DOI: 10.1080/08035250500423812.

- Miller KD, MT C, Lee PA. Fertility after unilateral cryptorchidism. Paternity, time to conception, pretreatment testicular location and size, hormone and sperm parameters. Horm Res 2001; 55: 249.

- Lee PA, Coughlin MT. Fertility after bilateral cryptorchidism. Evaluation by paternity, hormone, and semen data. Horm Res 2001; 55: 28.

- Park KH, Lee JH, JJ H. Histological evidences suggest recommending orchiopexy within the first year of life for children with unilateral inguinal cryptorchid testis. Int J Urol 2007; 14: 616. DOI: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2007.01788.x.

- Kogan SJ, Tennenbaum S, B G. Efficacy of orchiopexy by patient age 1 year for cryptorchidism. J Urol 1990; 144: 508. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39505-8.

- Tasian GE, Hittelman AB, GE K. Age at orchiopexy and testis palpability predict germ and Leydig cell loss: clinical predictors of adverse histological features of cryptorchidism. J Urol 2009; 182: 704. DOI: 10.1590/s1677-55382009000500033.

- Wood HM, Elder JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. J Urol 2009; 181: 452. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(09)79277-2.

- Caterino S, Lorenzon L, M C. Epididymal-testicular fusion anomalies in cryptorchidism are associated with proximal location of the undescended testis and with a widely patent processus vaginalis. J Anat 2014; 225: 473. DOI: 10.1111/joa.12222.

- Mollaeian M, V M, Elahi B. Significance of epididymal and ductal anomalies associated with undescended testis: study in 652 cases. Urology 1994; 43: 857. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(94)90152-x.

- Kim SO, Na SW, HS Y. Epididymal anomalies in boys with undescended testis or hydrocele: Significance of testicular location. BMC Urol 2015; 15: 108. DOI: 10.1186/s12894-015-0099-1.

- Cendron M, Huff DS, MA K. Anatomical, morphological and volumetric analysis: a review of 759 cases of testicular maldescent. J Urol 1993; 149: 570. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36151-7.

- Hrebinko RL, Bellinger MF. The limited role of imaging techniques in managing children with undescended testes. J Urol 1993; 150: 458. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35510-6.

- Tasian GE, Copp HL. Diagnostic performance of ultrasound in nonpalpable cryptorchidism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2011; 127: 119. DOI: 10.1016/j.yuro.2011.05.011.

- Elert A, Jahn K, A H. Population-based investigation of familial undescended testis and its association with other urogenital anomalies. J Pediatr Urol 2005; 1: 403. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2005.04.005.

- Engeler DS, Hosli PO, H J. Early orchiopexy: prepubertal intratubular germ cell neoplasia and fertility outcome. Urology 2000; 56: 144. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00560-4.

- Wenzler DL, DA B, Park JM. What is the rate of spontaneous testicular descent in infants with cryptorchidism? J Urol 2004; 171: 849. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000106100.21225.d7.

- Pyorala S, NP H, Uhari M. A review and meta-analysis of hormonal treatment of cryptorchidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1995; 80: 2795. DOI: 10.1210/jc.80.9.2795.

- Rajfer J, Walsh PC. The incidence of intersexuality in patients with hypospadias and cryptorchidism. J Urol 1976; 116: 769. DOI: 10.1016/0022-3468(77)90475-4.

- Hagberg S, Westphal O. Treatment of undescended testes with intranasal application of synthetic LH-RH. Eur J Pediatr 1982; 139: 285. DOI: 10.1007/bf00442181.

- Hadziselimovic F, Herzog B. Treatment with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue after successful orchiopexy markedly improves the chance of fertility later in life. J Urol 1997; 158: 1193. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00132.

- Cortes D, J T, Visfeldt J. Hormonal treatment may harm the germ cells in 1 to 3-year-old boys with cryptorchidism. J Urol 2000; 163: 1290. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200004000-00070.

Ultima atualização: 2023-02-22 15:40