14: Hydronephrosis and Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 25 minutos para ler.

Introduction

Hydronephrosis is defined as aseptic dilatation of the renal pelvis with or without the calyces. If it occurs before birth, this is called antenatal hydronephrosis (ANH). The presence of infected hydronephrosis denotes pyonephrosis while the presence of dilated ureter with the dilated renal pelvis is called hydroureteronephrosis (HUN).

The significance of ANH is attributed to being the most commonly encountered fetal urinary tract anomaly detected by ultrasonography.1 The majority of ANH is temporary and resolves spontaneously. The other pathological causes of ANH may be obstructive or non-obstructive. Obstructive causes can occur at any part of the urinary tract, but the most common pathology is ureteropelvic junction obstruction (UPJO). Non-obstructive etiologies comprise vesicoureteral reflux (VUR), non-obstructing non-refluxing megaureter, Prune-Belly syndrome, etc.

Many tools are used by pediatric urologists to measure the severity of ANH. The North American school relies mainly on the Society of Fetal Urology (SFU) grading system while measuring the APRPD is preferred in Europe.2

UPJO is defined as impairment of urine flow from the renal pelvis to the ureter with subsequent dilatation of the pelvicalyceal system. The presence of dilated renal pelvis with a non-dilated ureter by RBUS raises the suspicion of UPJO.

This chapter will address the embryology, epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, evaluation, treatment options, follow-up, and complications of ANH and UPJO. The remaining causes of ANH will be covered in other chapters.

Embryology

The kidneys develop from three overlapping sequential structures; the pronephros, the mesonephros, and the metanephros which are all derived from a region in the intermediate mesoderm known as the urogenital ridge.3 In the fourth week of gestation, the pronephros arises at the cervical region. Then, segmented parts of the intermediate mesoderm connect to form the pronephric duct which extends from the cervical region to the distal end of the embryo (cloaca). The pronephros is non-functional and regresses entirely by the end of the fourth gestational week.

After that, the mesonephros emerges caudal to the pronephros and pronephric duct persistence induces the formation of mesonephric tubules from the intermediate mesoderm which open into the pronephric duct forming the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct. The ureteric bud arises from the posterior aspect of the mesonephric duct.

The metanephros arises in the fifth week of development. After that, the ureteric bud joins the metanephric cap. The ureteric bud gives rise to the mucosa of the ureter, the renal pelvis, major and minor calyces, and collecting ducts. The mesenchyme surrounding the ureteric bud forms the lamina propria, the musculosa, and the adventitia of the ureter and renal pelvis. The proper development of the ureter and renal pelvis is dependent on reciprocal signaling between their mesenchymal and epithelial components. Abnormal signaling results in improper development and branching of the ureteric bud.Complete ureteral duplication results from the development of two ureteric buds on the same side while incomplete ureteral duplication arises from early bifurcation of the ureteric bud. In case of late bifurcation of the ureteric bud, a bifid renal pelvis is formed. Weigert-Meyer law describes the relationship between the two ureters in complete ureteral duplication. The upper moiety ureter is inserted into the bladder inferomedially, and it is the site of obstruction by a ureterocele or an ectopic ureter. On the other hand, the lower moiety ureter is inserted superolaterally into the bladder rendering it liable to VUR because of the short intramural tunnel. In addition, it can be affected by UPJO.

Eventually, ureteral canalization and ureteral wall maturation take place at the end of embryogenesis. Nonetheless, the latter continues beyond birth and this may elucidate the spontaneous resolution of many cases diagnosed with ANH. The fetal kidney starts to produce urine between the fifth and ninth weeks of gestation. Urine represents around 90% of the amniotic fluid which in turn is responsible for expansion of lung alveoli. Therefore, oligohydramnios is associated with pulmonary hypoplasia which is presented clinically as respiratory distress. The urogenital sinus gives rise to the bladder and urethra between the 10th and 12th weeks of pregnancy.

Epidemiology

ANH is the most common anomaly of the urinary tract detected by fetal ultrasonography. It affects one to five percent of all pregnancies. Fortunately, up to 80% of cases are temporary and resolve spontaneously. UPJO is the most common cause of pathological ANH and is typically treated by surgical intervention. It affects boys two times more than girls and the left side is involved more than the right one by two times. UPJO can affect both kidneys in 10% to 30% of cases.

UPJO is usually sporadic, but six cases with familial history were reported in the literature.4 UPJO can occur with other urological anomalies (e.g., VUR, multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK), horseshoe kidney, or duplicated kidney where the lower moiety is most commonly the site affected).

Etiology/Pathogenesis

The majority of ANH is temporary and improves spontaneously with time. Pathological causes that do not resolve postnatally can be due to obstructive or non-obstructive causes. Obstructive causes include; UPJO, obstructing megaureter, ureterocele, ectopic ureter, posterior urethral valve (PUV), urethral atresia in addition to neuropathic bladder. Non-obstructive etiologies comprise; VUR, non-obstructing non-refluxing megaureter, Prune-Belly syndrome.

Obstruction is accompanied by reduced renal blood flow (RBF), glomerular filtration rate (GFR), and potassium excretion, according to Josephson et al., and only a tiny percentage of this damage is mitigated by early intervention.5

Causes of UPJO

Primary UPJO can be caused by intrinsic, extrinsic, or intraluminal causes.6 Intrinsic obstruction is due to aperistaltic segment resulting from abnormal musculature or neurological development. This results in inappropriate urine flow from the renal pelvis to the ureter. Other causes of intrinsic obstruction comprise stenotic segment caused by excessive collagen deposition and congenital ureteral folds.

Extrinsic obstruction is caused by an aberrant crossing vessel that passes in front of the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ). This type of obstruction is usually intermittent and presented later at the age of seven years or above. Intraluminal obstruction is owing to a fibroepithelial polyp. This pathology affects anywhere in the urinary tract starting from the UPJ, till the urethra.7 Secondary UPJO is due to previous surgery, VUR, impacted stone, and post-inflammatory stricture.

UPJO-associated anomalies include; contralateral UPJO (10-30%), contralateral renal dysplasia, contralateral MCDK, unilateral renal agenesis (5%), duplicated collecting system where UPJO usually occurs in the lower moiety, horseshoe kidney, ectopic kidney, VUR (20-40%) and VACTERL syndrome.8,9

To avoid progressive intrapelvic pressure rise, the renal pelvis dilates to accommodate it preventing renal damage. Nevertheless, prolonged obstruction with failure of the compensatory mechanisms and loss of compliance result in increasing intrarenal pressure with subsequent renal damage. The earlier the obstruction during fetal life, the more renal damage is expected. Dietl’s crisis is an intermittent abdominal pain arising from distension of the pelvicalyceal system, and it is usually caused by a crossing vessel causing UPJO in children above five years.10

Evaluation and diagnosis

The diagnosis of ANH is based on measuring the APRPD which is five mm or more in the second trimester and seven mm or more in the third one.11 Fetal RBUS interpretation involves the following items; fetal sex, amniotic fluid index (AFI), gestational age, associated congenital anomalies, unilateral or bilateral hydronephrosis, degree of hydronephrosis, APRPD, parenchymal status in the form of parenchymal thickness and echogenicity, ureteral dilatation, bladder fullness and cycling in addition to its wall thickness, and urethral dilatation (Table 1).

Table 1 The ten questions to be addressed for the evaluation of antenatal hydronephrosis.

| 10 Questions | Question |

|---|---|

| 1 question related to the amniotic fluid | Amniotic fluid index (AFI) |

| 3 questions related to the fetus | Male or female |

| Gestational age | |

| Other congenital anomalies | |

| 3 questions related to the kidney | Grade and laterality of hydronephrosis |

| Dilatation of the upper ureter | |

| Renal Parenchyma (Parenchymal thickness and echogenicity) | |

| 3 questions related to the rest of the urinary tract | Dilatation of the lower ureter |

| Bladder (Bladder fullness and bladder wall thickness) | |

| Posterior urethral dilatation |

A full bladder wall thickness of more than two mm denotes thickened bladder wall regardless of the gestational age.12 The inability to visualize the bladder on several occasions is a sign of bladder exstrophy. In PUV, a full bladder with dilated posterior urethra can be seen giving a “keyhole sign”.

In the second trimester, ANH is classified into mild, moderate, and severe when the APRPD equals four to six mm, seven to ten mm, and more than ten mm, respectively. In the third trimester, prenatal hydronephrosis is classified into the same previous grades when the APRPD measures seven to nine mm, ten to 15 mm, and more than 15 mm, respectively (Table 2).11

Table 2 Antenatal hydronephrosis categories.

| Degree | 2nd trimester | 3rd trimester | % of ANH |

|---|---|---|---|

| mild | 4-7 mm | 7-9 mm | 56-88% |

| moderate | 7-10 mm | 9-15 mm | 10-30% |

| severe | >10 mm | >15 mm | 2-13% |

The baby should be re-evaluated three to seven days after birth and not earlier to avoid false-negative results caused by transient oliguria of the newborn, especially in the first 48 hours of life. Nevertheless, RBUS is done immediately following labor in cases of bilateral high-grade hydronephrosis, solitary kidney, oligohydramnios, or when PUV is suspected.

In North America, the SFU grading system is used for classifying hydronephrosis while the APRPD is used in Europe. The SFU classification of hydronephrosis is depicted in Table 3.13

Table 3 SFU grading system.

| SFU Grade | Descriptors |

|---|---|

| Grade 0 | no dilatation, calyceal walls are opposed to each other |

| Grade 1 (mild) | dilatation of the renal pelvis without dilatation of the calyces (can also occur in the extrarenal pelvis) |

| no parenchymal atrophy | |

| Grade 2 (mild) | dilatation of the renal pelvis (mild) and calyces (pelvicalyceal pattern is retained) |

| no parenchymal atrophy | |

| Grade 3 (moderate) | moderate dilatation of the renal pelvis and calyces |

| blunting of fornices and flattening of papillae | |

| mild cortical thinning may be seen | |

| Grade 4 (severe) | gross dilatation of the renal pelvis and calyces, which appear ballooned |

| loss of borders between the renal pelvis and calyces | |

| renal atrophy seen as cortical thinning |

The disadvantage of the SFU grading system is that being a little bit subjective without using the APRPD measurements resulting in its difficult correlation with ANH measurements. Based on the APRPD, hydronephrosis is graded into mild, moderate, and marked in which the APRPD measures 7-10 mm, 10-15 mm, and above 15 mm, respectively.14 The demerit of this classification is depending on only one item to grade hydronephrosis and neglecting the other parameters, such as parenchymal thickness and peripheral calyceal dilatation.

Therefore, a new classification of hydronephrosis has been proposed to avoid the cons of the previous two grading systems. The urinary tract dilatation (UTD) classification system relies on six RBUS findings; APRPD, calyceal dilation with the distinction between central and peripheral calyceal dilation postnatally, renal parenchymal thickness, renal parenchymal appearance, bladder abnormalities, and ureteral abnormalities. This grading system differentiates whether the RBUS findings were antenatal (normal, A1, A2, A3) or postnatal (normal, P1, P2, P3).15

If RBUS is unremarkable, it should be repeated after four to six weeks. In case of SFU grade 0 with APRPD of less than seven mm as a result of RBUS performed at the fourth to the sixth week, further follow-up is not needed. The effect of hydronephrosis grade on resolution rate was studied by.16

If postnatal hydronephrosis is detected with the presence of ureteral dilatation or suspicion of an abnormal bladder, voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) should be requested to exclude VUR, PUV in boys (Figure 1), neuropathic or non-neuropathic bladder dysfunction.

Figure 1 Voiding cystourethrogram depicting the classic appearance of posterior urethral valve.

In the presence of SFU grade 1 to 2 postnatal hydronephrosis or APRPD of less than 15 mm without ureteral dilatation or abnormal bladder in an asymptomatic infant, RBUS should be done every three to six months, and then every six to twelve months.17 Spontaneous resolution of hydronephrosis is usually expected in the first two years of life.

On the other hand, SFU grade 3 to 4 hydronephrosis or APRPD of 15 mm or more designates closer follow-up. In such a situation, VCUG is needed to exclude VUR, PUV, or bladder pathology. If VCUG is unremarkable, a dynamic renogram, especially MAG3 is advocated to have an idea about the split renal function and the presence of obstruction.

UPJO presents either prenatally or after birth. When it comes to the prenatal period, UPJO is the most common cause of pathological ANH 18. Postnatally, the patient can be asymptomatic with incidentally discovered hydronephrosis or may present with high-grade fever because of obstructed infected kidney or loin pain in older children. In children above five years with intermittent obstruction, aberrant crossing vessel should be suspected.

Hematuria is an uncommon presentation and usually follows flank trauma because the hydronephrotic kidney is more liable to trauma than the normal one. Palpable flank mass is rarely encountered in the era of ultrasonography.

RBUS alone can provide provisional diagnosis of the underlying pathology causing ANH. Dilated renal pelvis with non-dilated ureter signifies UPJO (Figure 2) while dilated ureter may be due to VUR or megaureter. In MCDK, the renal cysts are not connected to each other and the renal parenchymal is not preserved whereas the renal cysts are usually bilateral and communicable with preserved renal parenchyma. Ureterocele appears as a cyst within a cyst (the bladder), and it is associated with the upper pole of duplicated renal systems in 80% of cases while the remaining 20% are single-system ureteroceles which need puncture for system decompression. The key-hole appearance of dilated bladder and posterior urethra in boys is diagnostic of PUV.

Figure 2 Renal and bladder ultrasound showing left UPJO

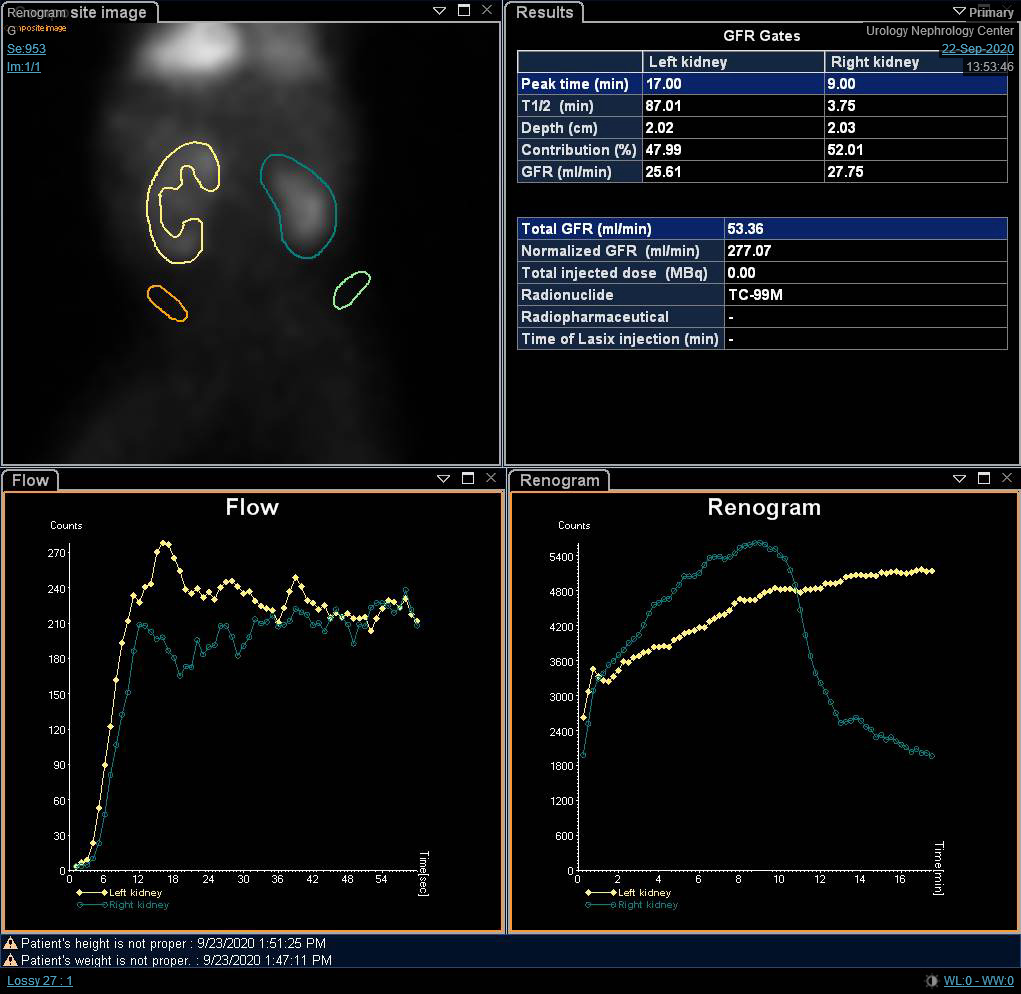

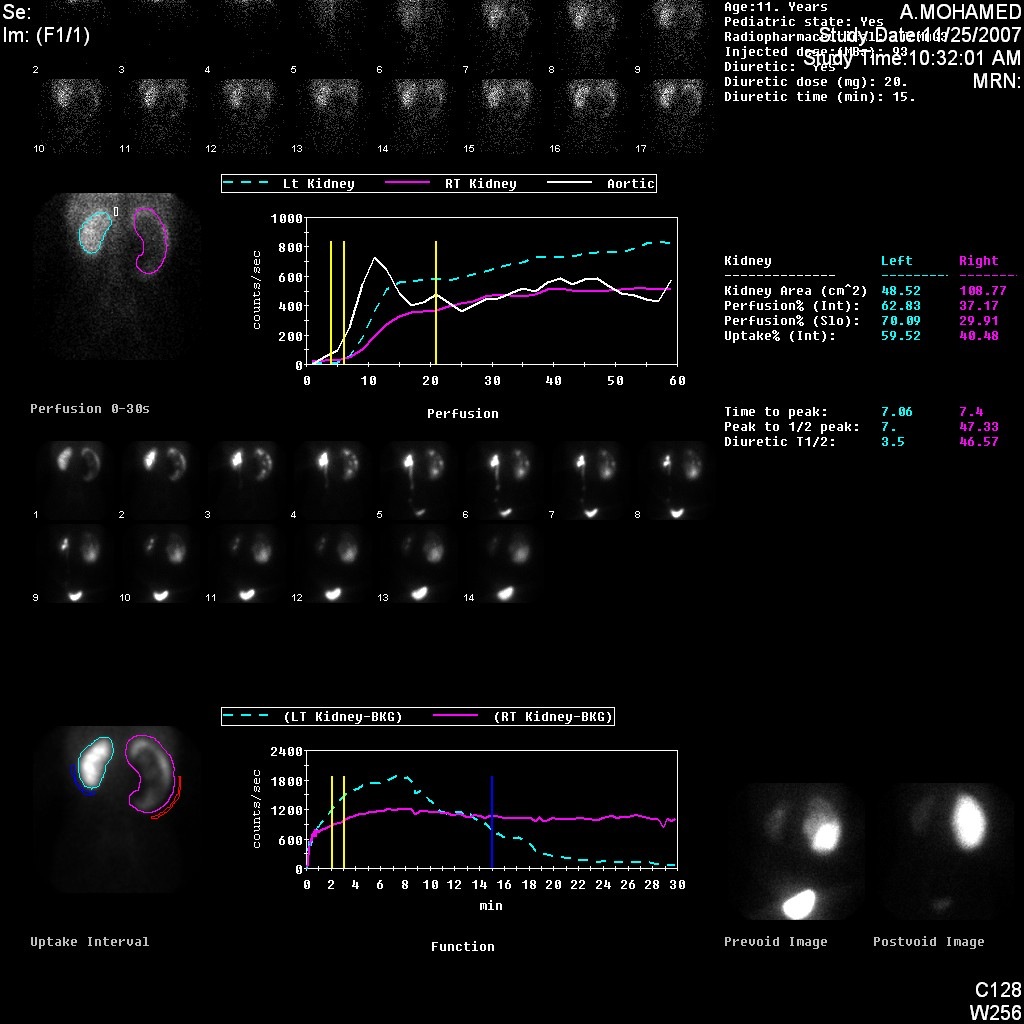

The role of renal scintigraphy cannot be neglected. Three types of renal scintigraphy are used, mercapto-acetyl triglycine (MAG3), di-ethylene tri-amene penta-acetic acid (DTPA), and dimercapto succinic acid (DMSA).18 All of them are labeled with metastable technetium-99 (99mTc). MAG3 undergoes both tubular and glomerular excretion. DTPA is only filtered by glomeruli, that is why it should not be requested in case of renal insufficiency. DMSA binds only to the proximal renal tubules. The half-life (t1/2) of 99mTc is six hours. Many North American centers have limited availability to the DMSA agent, limiting ability to perform this type of nuclear medicine study.

MAG3 and DTPA are dynamic, functional studies as opposed to DMSA. They provide information about the split renal function, and the presence of obstruction by taking serial images over time looking at uptake, excretion and drainage. However, MAG3 is preferred in children. DMSA is a static scan that can detect not only the split function but also the presence of renal scarring. Renography is done from the fourth to the sixth week to make sure that renal maturation has been reached.19

If renal scintigraphy is done before renal maturation, the scan may depict high residual cortical activity, retaining up to 50% or more of the peak. MAG3 or DTPA are requested when UPJO or UVJ are suspected whereas DMSA may done in cases of VUR as part of a top-down approach (Figure 3) Renograms have three phases. The first one is the vascular phase which reflects renal blood flow and takes up to ten seconds. The second one is the parenchymal phase which represents the renal uptake and occurs from the tenth second to the fifth minute following isotope injection. Eventually, the excretory phase follows representing radio-isotope excretion into the renal pelvis.

Figure 3 DMSA scan depicting reduced radio-isotope uptake with renal scarring on the left side

Some precautions are taken into consideration prior to renal scintigraphy e.g. adequate hydration or even intravenous infusion of normal saline at a rate of 10 mL/ kg with a maintenance of 4 mL/kg /hour and urethral catheter fixation for emptying the bladder to avoid false-positive results of obstruction. There is no consensus regarding the timing of diuretic injection. Routinely, it is injected 20 minutes following the radioactive isotope (F+20). To avoid pooling of the isotope in dilated pelvicalyceal systems, furosemide is recommended to be injected 15 minutes before the radioactive material (F-15). Other authors advocate injecting furosemide at the same time with a radioactive isotope (F+0). The dose of furosemide (Lasix) is 1 mg/kg in early infancy and 0.5 mg/ kg later on with a maximal dose of 40 mg.

Although the differential function is the most significant variable in the renal scan, renography curves and t1/2 may indicate a provisional diagnosis of obstruction. O’Reilly described four curves for dynamic renogram; type I curve representing normal uptake and excretion (bell-shaped curve) (Figure 4), type II curve representing obstructed pattern with no response to diuretic (Figure 5) and Figure 6), type IIIa curve that initially rises then drops following diuretic injection, type IIIb curve that initially rises then neither drops nor continues to rise (equivocal), and type IV in which a delayed decompensation occurs 15 minutes following furosemide injection.20

Figure 4 DTPA scan showing bell-shaped non-obstructed curve

Figure 5 DTPA scan demonstrating obstructed curve of the left kidney

Figure 6 DTPA scan showing obstructed curve of the right kidney with prolonged t1/2.

T1/2 of less than 10 minutes is normal while t1/2 of more than 20 minutes signifies obstruction. Values in between are considered equivocal. However, many advocate against solely using the t1/2 value to determine whether there is obstruction, as the curve height, shape, patient fluid status, drainage of the bladder, and overall kidney function can influence this value.

To confirm the diagnosis of UPJO, RBUS is done followed by renal scintigraphy to provide both structural and functional information (Figure 7) In debatable cases, magnetic resonance urography (MRU) may be requested. VCUG is not needed as long as the ureter is not dilated while intravenous urography is obsolete in modern pediatric urology.

Figure 7 DTPA scan showing delayed drainge of the left kidney caused by left UPJO

By means of RBUS, dilated renal pelvis with non-dilated ureter is noted. As mentioned before, the APRPD should be measured and if it is more than 30 mm, renal scintigraphy should be requested because the incidence of renal function deterioration is high at this degree of hydronephrosis.

The use of duplex ultrasonography to suggestion obstruction cannot be neglected, although the accuracy of these findings may not be super high. The presence of ureteral jets from the ureter to the bladder excludes ureteral obstruction. Resistive index (RI) of 0.7 or more denotes obstruction. It is measured by subtracting the end-diastolic velocity (EDV) of the renal artery from its peak-systolic velocity (PSV) and the result is divided by the PSV. The rationale beyond the use of RI is that obstructive uropathy is ultimately accompanied by diminished renal blood flow. VCUG is not requested in the context of UPJO unless there is dilated lower end of the ureter in cases of UPJO secondary to VUR.

Although contrast-enhanced computed tomography is generally avoided in children because of hazardous ionizing radiation, it may be used to detect the presence of a crossing vessel in the arterial (cortico-medullary) phase. Intravenous urography (IVU) is no longer recommended in modern pediatric urology. All contrast studies should be avoided unless the renal function tests are within the normal values.

MRI can be done in equivocal cases in which RBUS is not conclusive. Dynamic MRI with gadolinium has gained attention in the last few years because of its ability to give information not only about the anatomical diagnosis but also regarding the function. It can assess the split renal function by measuring the volume of enhancing parenchyma using a special software by a radiation physicist to perform this calculation. Furthermore, calculation of the renal transit time, which is the time difference between cortical enhancement and ureter appearance, can be used to confirm obstruction.

Retrograde uretero-pyelography may be used pre-operatively to confirm the diagnosis in doubtful cases or if the surgeon is planning for dorsal lumbotomy to exclude concomitant ureteral stricture. Last but not least, some biochemical markers have been used to detect renal tubular damage owing to obstruction e.g. β2-microglobulin, N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase (NAG), and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-β1).

Treatment options and their outcomes

Prenatal management of ANH

Prenatal intervention is rarely needed nowadays and it only considered in those with severe lower urinary tract obstruction e.g. bilateral high-grade hydronephrosis with oligohydramnios.21 In absence of life-threatening conditions after the 20th week of gestation, the pregnancy should not be terminated, nor should delivery plans be influenced (e.g., early induction of labor).

Postnatal management of ANH

Physical examination cannot be neglected in cases diagnosed with ANH. For instance; abdominal mass may be felt in UPJO or MCDK while undescended testis and deficient anterior abdominal wall musculature are found in Prune- Belly syndrome in addition to palpable bladder in PUV.

Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis (CAP) is recommended in SFU grade 3 and 4 hydronephrosis or APRPD of 15 mm or more to reduce the rate of UTIs in the first two years of life.17 However, there are numerous studies of ANH (in the absence of reflux or megaureter/hydroureter) that show no benefit for CAP in patients with isolated high-grade hydronephrosis (grade 3-4).22

CAP in the first two months comprises amoxicillin and trimethoprim at a dose of 10 to 20 mg/kg once daily and 2 mg/kg once daily, respectively. After that age, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX) are prescribed at a dose of mg/ kg/ day. Early prescription of nitrofurantoin can cause hemolytic anemia or respiratory distress syndrome while sulfamethoxazole in the first two months causes kernicterus.

Common side effects of nitrofurantoin include gastrointestinal disturbance and skin reactions. Adverse events associated with TMP/SMX are mainly due to the sulfamethoxazole component, most commonly skin reactions. Antibiotic exposure during the first year of life is associated with an increased risk of developing atopic diseases, including eczema, asthma, and allergy later on.23 This finding is attributed to the hygiene hypothesis, which proposes that growing up in an extremely hygienic environment with minimal microbial exposure may increase atopic immune responses. Another demerit of CAP is development of antibiotic resistance.

The main challenge for pediatric urologists is to distinguish UPJO that is going to resolve spontaneously from that will cause renal function deterioration. The former needs follow-up whereas the latter requires intervention.

Indications of definitive intervention include the presence of symptoms (pain, febrile UTI), palpable kidney, and APRPD of more than 40 mm.24 Other indications comprise; progressive hydronephrosis during follow-up, split renal function less than 40% and deterioration of split function by 10% or more.25 In cases of symptomatic neglected UPJO with a split renal function of less than 10%, nephrectomy is advocated. However, some pediatric urologists prefer early drainage by nephrostomy tube or internal ureteral stent and then re-evaluation.

Anderson-Hynes dismembered pyeloplasty (AHDP) remains the gold standard operation for definitive treatment of UPJO.17 In this technique, the dynamic or stenotic segment is excised, the ureter is spatulated against the lower pole of the kidney followed by anastomosing the renal pelvis to the spatulated ureter over a transanastomotic stent. For a highly inserted ureter, Foley Y-V plasty was previously preferred, but it has been largely replaced by AHDP. Foley Y-V pyeloplasty may be appropriate for UPJO in setting of a horseshoe kidney.

The vascular hitch technique is still having a role in modern pediatric urology because it is less demanding and less time-consuming than AHDP. Moreover, its success rate is up to 90% with less complication rates (e.g., urinary leakage and anastomotic stricture). It involves elevation of the crossing vessel anteriorly away from the UPJ. However, concomitant intrinsic obstruction should be excluded by diuretic test to avoid technical failure.

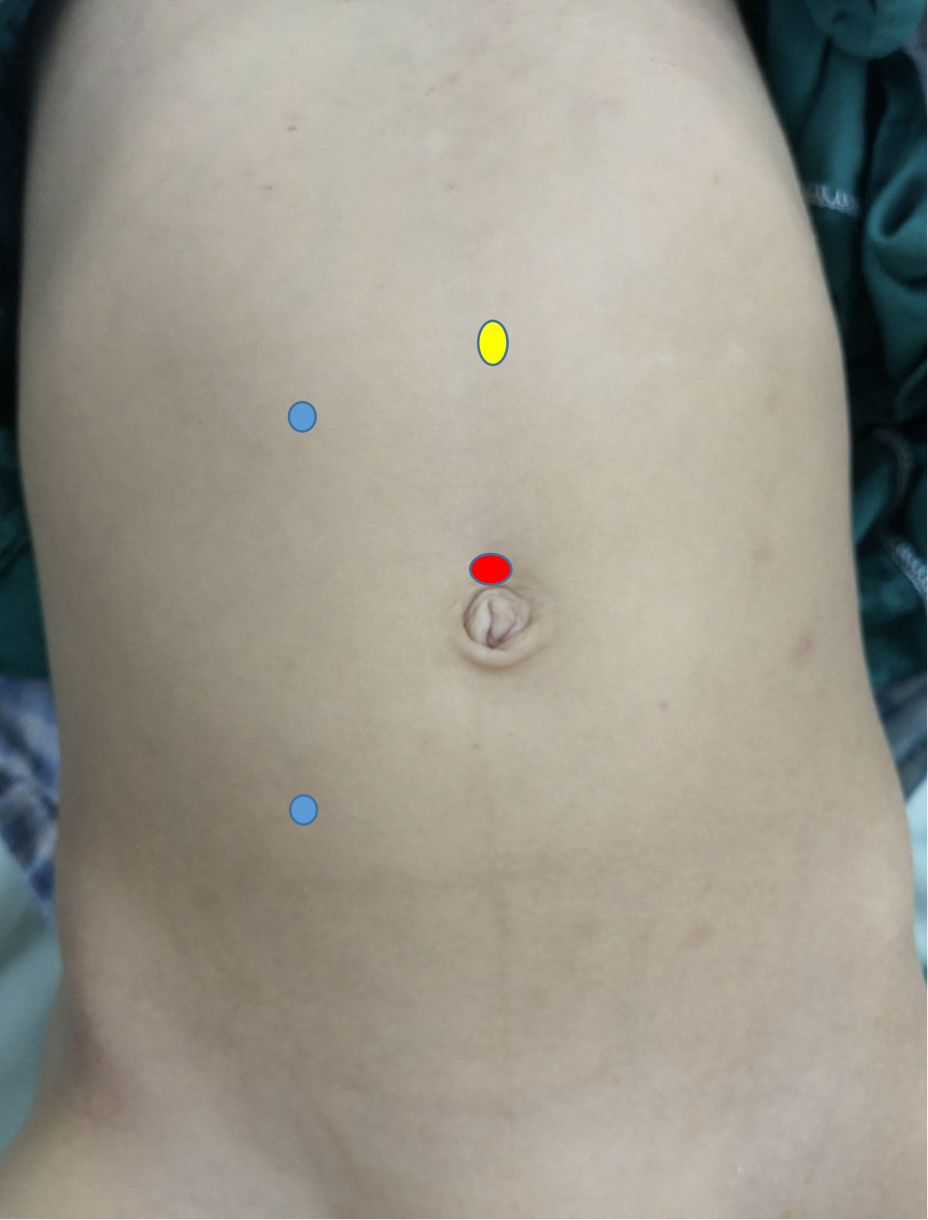

The patient is placed in the lateral flank position where the targeted side is facing upwards. The incision is made anterior subcostal (Figure 8) with an extraperitoneal approach. After splitting or dividing the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles with medial retraction of the peritoneum and extraperitoneal (pararenal) fat, the two layers of Gerota’s fascia are opened. The UPJ is identified and two stay sutures are placed proximal and distal to the UPJ prior to dividing it.

Figure 8 Anterior lumbar incision in front of the tip of the last rib for open left pyeloplasty

The UPJ is dismembered between the two stay sutures. Reduction pyeloplasty is done only in cases of marked redundant renal pelvis in which the excess renal pelvis is trimmed. On the other hand, other authors concluded that excision of the renal pelvis (reduction pyeloplasty) is not needed in most cases of dismembered pyeloplasty.26 They found that cases with or without reduction pyeloplasty had similar surgical outcomes. The next step is to anastomose the two limbs of the renal pelvis to the two ones of the spatulated ureter.

The first suture to be taken is that of the angle followed by the posterior suture line, inserting the transanastomotic stent and completing the anterior suture line. The remaining two limbs of the renal pelvis are sutured to each other. The sutures used are 6-0 vicryl (or other absorbable monofilament suture) either in a continuous or interrupted manner. In the very beginning of the learning curve, start with interrupted sutures until mastering the technique.

Another approach for open pyeloplasty other than the anterior lumbar approach is posterior or dorsal lumbotomy (DL) (Figure 9)27 It is the oldest approach used to gain access to the kidney and the upper ureter. However, it is not used nowadays on a wide scale especially in children. DL can be done via one of the following skin incisions; Gil-Vernet vertical incision along the lateral edge of sacrospinalis muscle, Lurz modification vertical incision following the lateral border of quadratus lumborum muscle, or transverse incision following Langer’s lines.

Figure 9 Dorsal lumbotomy incision for left-sided open pyeloplasty

The main advantage of DL is easy access to the retroperitoneum via two simple incisions without muscle cutting. Large hydronephrotic kidney is no longer considered a contraindication for DL because the kidneys are usually more mobile in children. However, DL should be avoided in renal malrotation or malposition.

Although open pyeloplasty is the standard technique in young age with a success rate of 95%, laparoscopic and robot-assisted techniques have comparable success rates.28 Minimally-invasive techniques have the advantage of less pain, shorter postoperative hospital stay and minimal scars at the trocar sites. Nevertheless, they require a special armamentarium with subsequent higher costs in addition to a relatively longer training curve. The use of the da Vinci® robotic system made intracorporeal suturing easier than before.

Laparoscopic and robotic-assisted pyeloplasty can be done via a transperitoneal or retroperitoneal approach.28 The transperitoneal approach is more commonly used because of the evident anatomical landmarks and the relatively wide working space. Nonetheless, it has more complications than the retroperitoneal one in the form of organ injury and intestinal obstruction. In order to reduce the operative time and bowel manipulation in transperitoneal laparoscopic pyeloplasty, the transmesocolic approach is used to directly mobilize the left UPJ without colonic reflection.29

In laparoscopic pyeloplasty, at least three ports are used, one at the umbilicus by open method for the camera, and two working ports. The first working port is at the subcostal line while the second one is at the spino-umbilical line, and both are preferred to be at the pararectal line (Figure 10) In robotic pyeloplasty, the camera port is just superior to the umbilicus while the two working ports are midway between the umbilicus and the anterior superior iliac spine, and finger below the costal margin at the pararectal line. The assistant port is placed midway between the umbilicus and the xiphisternum (Figure 11)

Figure 10 Port distribution for laparoscopic right-sided dismembered Anderson-Hynes pyeloplasty

Figure 11 Port distribution for robotic right-sided pyeloplasty

Irrespective of the approach used, the main goal of pyeloplasty is to have a patent, dependent, funnel-shaped, water-tight, and tension-free anastomosis between the ureter and the renal pelvis. Transanastomotic stent may be external or internal or none at all.30

The external stent is exteriorized via the renal parenchyma or the renal pelvis and is usually left for ten to fourteen days. It is crucial to make sure that there is at least one pore within the renal pelvis to avoid stent obstruction by the ureter itself. In addition, avoid leaving pores outside the pelvicalyceal system for fear of postoperative urinary leakage.

One of the best ways to confirm that the lower coil of the double pigtail (double J) stent has reached the bladder is to fill the bladder via a previously fixed urethral catheter and to check the backflow. Another tip for placement is to use the smallest diameter stent available and place it over a hydrophilic wire. This has less chance of getting stuck at the ureterovesical junction and causing injury there, which has been reported. An internal stent is kept for one to four weeks and then removed using cystoscopy. Needing an additional session of anesthesia is a drawback of the internal stent. Leaving a tube drain is not a routine practice except in difficult or recurrent cases.

Many surgeons prefer the use of external stent even in laparoscopic and robot-assisted approaches to avoid a second general anesthesia for internal stent removal.31,32 Externalized pyeloureteral Salle intraoperative pyeloplasty stent is another effective alternative to internal stenting because its cost is less than that of a second session of general anesthesia.32

In case of the redundant renal pelvis with a long segment defect, Culp-DeWeerd spiral flap or Scardino-Prince vertical flap are recommended. If the renal pelvis is insufficient for making a flap to bridge the gap between the renal pelvis and the ureter, ureterocalycostomy can be an option. In ureterocalycostomy, the ureter is anastomosed to the lower calyx after amputating the lower pole of the kidney.

Endoscopic endopyelotomy is an option for short-segment stricture (less than two cm) in a salvageable kidney after excluding the presence of a crossing vessel.33 It can be done for primary or recurrent cases via either antegrade or retrograde approach using a cold knife or Holmium laser. It has lower success rates compared to AHDP (70% Vs 95%, respectively). It is contraindicated in the presence of active urinary tract infection, crossing vessel, and bleeding diathesis. For failed pyeloplasties, redo pyeloplasty has higher success rates (95-99%) compared to endoscopic endopyelotomy (39%), especially in young children and stricture segments of more than one centimeter.33

Complications

If left untreated, UPJO can result in function deterioration of the affected kidney till complete function loss. Secondary hypertension is an uncommon complication. Complications of pyeloplasty are either early or late. Early complications include urinary leakage from the wound or the drain with or without collection, non-draining external stent, displaced internal stent, hematuria, fever, and wound infection. Late complications involve technical failure or restenosis.34

Urinary leakage is managed by urinary diversion in the form of percutaneous nephrostomy or retrograde internal stent placement. It may be sometimes attributed to the presence of stent pores outside the kidney with subsequent leakage into the retroperitoneum. In the case of sizable perinephric collection, a percutaneous drain is advocated. A non-draining external stent may be due to a blood clot obstructing the stent or the absence of pores in the stent part within the renal pelvis while the rest of the drainage pores are obstructed by the ureter. The former cause is managed by stent flushing while the latter is treated with stent withdrawal.

Hematuria is usually managed conservatively by adequate hydration with or without hemostatic use whereas wound infection is treated with culture-based antimicrobial in addition to frequent wound dressing. In case of fever, the persistent obstruction should be excluded through RBUS followed by intravenous antibiotics.

The management of failed pyeloplasty depends mainly on the split renal function. In symptomatic obstructed poorly functioning kidney with a split function of less than 10-15%, nephrectomy is considered. In a salvageable kidney, redo pyeloplasty or sometimes endoscopic phlebotomy is done. The timing of intervention is at least three months after the primary surgery.

Suggested follow-up

In cases with unilateral ANH, RBUS should be done once in the third trimester. If ANH is bilateral, RBUS should be performed on monthly basis until delivery, depending on the presence of signs suggestive of the lower urinary tract obstruction e.g. progressive hydronephrosis, oligohydramnios, or thickened bladder wall.11

Conservative management of asymptomatic pelvic dilatations with a split renal function of more than 40% is usually advocated because the majority of cases experience spontaneous resolution. Progressive hydronephrosis or renal function deterioration during observation is an accepted indication of definitive intervention to prevent subsequent further damage.

There is no consensus regarding the follow-up following pyeloplasty and what is published in literature is either expert opinion or anecdotal experience.35 At our institute, the patient is reviewed clinically after two weeks in case of external stent placement or after six weeks in case of internal stent fixation. Three months following surgery, RBUS is requested, and the grade of hydronephrosis and APRPD are observed. If there is an improvement in the aforementioned parameters, the next follow-up will be one year after surgery utilizing RBUS. In case of static RBUS, the upcoming follow-up will be three months later by RBUS. If progressive hydronephrosis is noticed or the patient is symptomatic, MAG3 scan should be requested.

Suggested readings

- Han HH, Ham WS, Kim JH, Hong CH, Choi YD, Han SW. Transmesocolic approach for left side laparoscopic pyeloplasty: Comparison with laterocolic approach in the initial learning period. Yonsei Medical Journal 2013; 54 (1): 197–203. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.1.197.

- Jackson L, Woodward M, Coward RJ. The molecular biology of pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction. Pediatric Nephrology 2018; 33 (4): 553–571. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-017-3629-0.

- Gopal M, Peycelon M, Caldamone A, Chrzan R, El-Ghoneimi A, Olsen H. Management of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children—a roundtable discussion. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2019; 15 (4): 322–329. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.010.

- Chertin B, Pollack A, Koulikov D, Rabinowitz R, Hain D, Hadas-Halpren I. Conservative treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children with antenatal diagnosis of hydronephrosis: lessons learned after 16 years of follow-up. European Urology 2006; 49 (4): 734–739. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(08)70420-2.

- Värelä S, Omling E, Börjesson A, Salö M. Resolution of hydronephrosis after pyeloplasty in children. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2021; 17 (1): 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.10.031.

- Sarihan H, Comert HSY, İmamoğlu M, Basar D. Reverse tubularized pelvis flap method for the treatment of long segment ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Medical Principles and Practice 2020; 29 (2): 128–133. DOI: 10.1159/000502028.

Key Points

- Dilated renal pelvis with non-dilated ureter in renal and bladder ultrasonography is highly suggestive of UPJO.

- Consider intervention in one of the following scenarios; Symptomatic UPJO (Sepsis, significant pain, or stone formation) APRPD of more than 5 centimeters Progressive hydronephrosis Renal function deterioration by more than 10% on serial renal scintigraphy scans. Renal split function of less than 40% with prolonged t1/2.

- Spatulate the ureter against the lower pole of the kidney during Anderson-Hynes dismembered pyeloplasty.

- Avoid manipulation of the ureter during creating pelviureteral anastomosis.

- Make sure that all the external stent pores are inside the pelvicalyceal system to avoid urinary leakage.

References

- Oliveira EA, Oliveira MCL, Mak RH. Evaluation and management of hydronephrosis in the neonate. Current Opinion in Pediatrics 2016; 28 (2): 195–201. DOI: 10.1097/mop.0000000000000321.

- Onen A. An alternative grading system to refine the criteria for severity of hydronephrosis and optimal treatment guidelines in neonates with primary UPJ-type hydronephrosis. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2007; 3 (3): 200–205. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.08.002.

- Shapiro E. Clinical implications of genitourinary embryology. Current Opinion in Urology 2009; 19 (4): 427–433. DOI: 10.1097/mou.0b013e32832c90ff.

- Beksaç S, Balcı S, Yapıcı Z, Özyüncü Ö. Prenatally Diagnosed Ureteropelvic Junction Obstruction in Three Siblings of one Family: A Case Report. Gynecology Obstetrics & Reproductive Medicine 2008; 14 (3): 193–195.

- Josephson S. Antenatally detected, unilateral dilatation of the renal pelvis: a critical review. 1. Postnatal non-operative treatment 20 years on\–is it safe? Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology 2002; 36 (4): 243–250. DOI: 10.1080/003655902320248191.

- Krajewski W, Wojciechowska J, Dembowski J, Zdrojowy R, Szydełko T. Hydronephrosis in the course of ureteropelvic junction obstruction: An underestimated problem? Current opinions on the pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Advances in Clinical and Experimental Medicine: Official Organ Wroclaw Medical University 2017; 26 (5): 857–864. DOI: 10.17219/acem/59509.

- Atwa AM, Abdelhalim A, Edwan M, Soltan M, Hashim A, Abdelhameed M. Holmium Laser En Bloc Resection of Urethral Polyps in Children: A Case Series. Journal of Endourology Case Reports 2020; 6 (4): 457–460. DOI: 10.1089/cren.2020.0099.

- Houat AP, Guimarães CT, Takahashi MS, Rodi GP, Gasparetto TP, Blasbalg R. Congenital anomalies of the upper urinary tract: a comprehensive review. Radiographics 2021; 41 (2): 462–486. DOI: 10.1148/rg.2021219009.

- Alagiri M, Polepalle SK. Dietlś crisis: an under-recognized clinical entity in the pediatric population. International Braz j Urol 2006; 32: 451–453. DOI: 10.1590/s1677-55382006000400012.

- Yalçınkaya F, Özçakar ZB. Management of antenatal hydronephrosis. Pediatric Nephrology 2020; 35 (12): 2231–2239. DOI: 10.1201/b13478-107.

- Has R, Sarac Sivrikoz T. Prenatal diagnosis and findings in ureteropelvic junction type hydronephrosis. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2020; 8 (492). DOI: 10.3389/fped.2020.00492.

- Hodhod A, Capolicchio J-P, Jednak R, El-Sherif E, El-Doray AE-A, El-Sherbiny M. Evaluation of urinary tract dilation classification system for grading postnatal hydronephrosis. The Journal of Urology 2016; 195 (3): 725–730. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.10.089.

- ElSheemy MS. Postnatal management of children with antenatal hydronephrosis. African Journal of Urology 2020; 26 (1): 1–14. DOI: 10.1186/s12301-020-00097-8.

- Chow JS, Koning JL, Back SJ, Nguyen HT, Phelps A, Darge K. Classification of pediatric urinary tract dilation: the new language. Pediatric Radiology 2017; 47 (9): 1109–1115. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-017-3883-0.

- Elmaci AM, Dönmez Mİ. Time to resolution of isolated antenatal hydronephrosis with anteroposterior diameter≤ 20 mm. European Journal of Pediatrics 2019; 178 (6): 823–828. DOI: 10.1007/s00431-019-03359-y.

- Engin MMN. Management of Infants Diagnosed with Antenatal Hydronephrosis and Determining the Need for Surgical Intervention. 2020. DOI: 10.33309/2639-9164.030202.

- Hashim H, Woodhouse CR. Ureteropelvic junction obstruction. European Urology Supplements 2012; 11 (2): 25–32. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-62703-206-3_4.

- Riccabona M. Assessment and management of newborn hydronephrosis. World Journal of Urology 2004; 22 (2): 73–78. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-004-0405-0.

- Taghavi R, Ariana K, Arab D. Diuresis renography for differentiation of upper urinary tract dilatation from obstruction F+ 20 and F-15 methods. 2007. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.06.721.

- Clayton DB, Brock JW. Current state of fetal intervention for lower urinary tract obstruction. Current Urology Reports 2018; 19 (1): 1–8. DOI: 10.1007/s11934-018-0760-9.

- Chamberlin JD, Braga LH, Davis-Dao CA, Herndon CA, Holzman SA, Herbst KW. Continuous antibiotic prophylaxis in isolated prenatal hydronephrosis. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2022. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.03.027.

- Ahmadizar F, Vijverberg SJ, Arets HG, Boer A, Lang JE, Garssen J. Early‐life antibiotic exposure increases the risk of developing allergic symptoms later in life: a meta‐analysis. Allergy 2018; 73 (5): 971–986. DOI: 10.1111/all.13332.

- Dhillon H. Prenatally diagnosed hydronephrosis: the Great Ormond street experience: Perinatal Urology. British Journal of Urology Supplement 1998; 81 (2): 39–44. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.0810s2039.x.

- Hafez AT, McLorie G, Bägli D, Khoury A. Analysis of trends on serial ultrasound for high grade neonatal hydronephrosis. The Journal of Urology 2002; 168 (4 Part 1): 1518–1521. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210010-00072.

- Morsi HA, Mursi K, Abdelaziz AY, ElSheemy MS, Salah M, Eissa MA. Renal pelvis reduction during dismembered pyeloplasty: is it necessary? Journal of Pediatric Urology 2013; 9 (3): 303–306. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.03.002.

- Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Bägli DJ, Mahdi M, Salle JLP, Khoury AE. Comparison of flank, dorsal lumbotomy and laparoscopic approaches for dismembered pyeloplasty in children older than 3 years with ureteropelvic junction obstruction. The Journal of Urology 2010; 183 (1): 306–311. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.09.008.

- Başataç C, Boylu U, Önol FF, Gümüş E. Comparison of surgical and functional outcomes of open, laparoscopic and robotic pyeloplasty for the treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Turkish Journal of Urology 2014; 40 (1). DOI: 10.5152/tud.2014.06956.

- Han HH, Ham WS, Kim JH, Hong CH, Choi YD, Han SW. Transmesocolic approach for left side laparoscopic pyeloplasty: Comparison with laterocolic approach in the initial learning period. Yonsei Medical Journal 2013; 54 (1): 197–203. DOI: 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.1.197.

- Yiee JH, Baskin LS. Use of internal stent, external transanastomotic stent or no stent during pediatric pyeloplasty: a decision tree cost-effectiveness analysis. The Journal of Urology 2011; 185 (2): 673–681. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.09.118.

- Helmy T, Blanc T, Paye-Jaouen A, El-Ghoneimi A. Preliminary experience with external ureteropelvic stent: alternative to double-j stent in laparoscopic pyeloplasty in children. The Journal of Urology 2011; 185 (3): 1065–1070. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.056.

- Chu DI, Shrivastava D, Batavia JP, Bowen DK, Tong CC, Long CJ. Outcomes of externalized pyeloureteral versus internal ureteral stent in pediatric robotic-assisted laparoscopic pyeloplasty. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2018; 14 (5): 1–. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.04.012.

- Lucas JW, Ghiraldi E, Ellis J, Friedlander JI. Endoscopic management of ureteral strictures: an update. Current Urology Reports 2018; 19 (4): 1–7. DOI: 10.1007/s11934-018-0773-4.

- Khemchandani SI. Outcome analysis of pediatric pyeloplasty in varied presentation in developing countries. Urological Science 2019; 30 (6). DOI: 10.4103/uros.uros_31_19.

- Gopal M, Peycelon M, Caldamone A, Chrzan R, El-Ghoneimi A, Olsen H. Management of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children—a roundtable discussion. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2019; 15 (4): 322–329. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.010.

- Freilich DA, Nguyen HT, Borer J, Nelson C, Passerotti CC. Concurrent management of bilateral ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children using robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery. International Braz j Urol 2008; 34: 198–205. DOI: 10.1590/s1677-55382008000200010.

- Jackson L, Woodward M, Coward RJ. The molecular biology of pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction. Pediatric Nephrology 2018; 33 (4): 553–571. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-017-3629-0.

- Chertin B, Pollack A, Koulikov D, Rabinowitz R, Hain D, Hadas-Halpren I. Conservative treatment of ureteropelvic junction obstruction in children with antenatal diagnosis of hydronephrosis: lessons learned after 16 years of follow-up. European Urology 2006; 49 (4): 734–739. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(08)70420-2.

- Värelä S, Omling E, Börjesson A, Salö M. Resolution of hydronephrosis after pyeloplasty in children. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2021; 17 (1): 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.10.031.

- Sarihan H, Comert HSY, İmamoğlu M, Basar D. Reverse tubularized pelvis flap method for the treatment of long segment ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Medical Principles and Practice 2020; 29 (2): 128–133. DOI: 10.1159/000502028.

Ultima atualização: 2024-03-17 22:36