09: Fundamentos da endoscopia pediátrica

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 21 minutos para ler.

Introdução

O advento da instrumentação endoscópica revolucionou o campo da urologia, melhorando tanto o potencial diagnóstico quanto o terapêutico para os distúrbios urológicos. Ao longo das últimas décadas, os avanços tecnológicos permitiram a miniaturização de instrumentos urológicos para adultos para uso no trato geniturinário pediátrico. Cistouretroscopia, ureteroscopia e nefroscopia são instrumentos indispensáveis para o urologista pediátrico diagnosticar e tratar condições que vão desde refluxo vesicoureteral, nefrolitíase e válvulas uretrais posteriores até anomalias congênitas e trauma geniturinário. Procedimentos cirúrgicos anteriormente abertos foram transformados em procedimentos endoscópicos menos invasivos, que permitem recuperação mais rápida de nossos pacientes.

Neste capítulo, discutiremos o papel da endoscopia do trato inferior e superior no paciente pediátrico e forneceremos um guia para a avaliação, o diagnóstico e o tratamento de condições que requerem endoscopia pediátrica.

História da Endourologia

Antes da chegada dos instrumentos endoscópicos, os procedimentos cirúrgicos envolvendo orifícios corporais eram limitados ao uso de espéculos, sondas e bisturis.1 O primeiro protótipo endoscópico foi introduzido por Phillip Bozzini em 1806. O ‘lichtleiter’ ou ‘condutor de luz’ consistia em um funil longo colocado em uma caixa coberta de pele de tubarão e uma vela para iluminação. Espelhos angulados dentro da caixa direcionavam a luz para o corpo humano. Foi usado para examinar a vagina, a bexiga e a nasofaringe, mas nunca foi usado no interior de um paciente.1,2,3,4 Em 1853, Antoine Desormeaux introduziu o primeiro cistoscópio funcional e é creditado como o ‘pai da cistoscopia’.2,3,4 Os avanços tecnológicos incluíram um endoscópio menor, uma lâmpada a querosene e um espelho côncavo com um orifício central que melhorou a iluminação do dispositivo.2 Ele é o primeiro conhecido a usar seu cistoscópio primitivo em um paciente para a excisão de um papiloma uretral.4 As principais complicações incluíam queimaduras térmicas associadas à fonte de luz a querosene e iluminação insuficiente.5 Em 1877, o urologista alemão Maximilian Nitze utilizou um telescópio miniaturizado com uma série de lentes ao longo de um tubo oco para ampliar a imagem e um filamento elétrico de platina refrigerado a água na extremidade para iluminação.6 Quando Thomas Edison inventou a lâmpada em 1878, o dispositivo de Nitze foi modificado com a adição de uma lâmpada à ponta do cistoscópio.2,7 O prisma de Amici, desenvolvido em 1906, permitiu que imagens deslocadas em 90˚ aparecessem na orientação correta, e essa tecnologia foi incorporada ao projeto dos cistoscópios daí em diante.7

A descoberta de que o vidro era um condutor de luz melhor do que o ar abriu caminho para projetos de fibra óptica. Harold Hopkins inventou o sistema de lentes em bastonete em 1951 ao agrupar e dispor fibras de vidro de 0,1 mm de diâmetro coaxialmente à ocular para transmitir imagens.7 O ‘fibroscópio’, acoplado a uma fonte de luz externa, melhorou a transmissão de luz > 80 vezes, e o sistema foi patenteado em 1959.7 Essa tecnologia lançou as bases para o cistoscópio rígido moderno.

Além dos avanços endoscópicos, os sistemas de câmera também melhoraram ao longo do tempo. Com a miniaturização do equipamento de câmera e a invenção de um dispositivo de acoplamento de carga, as imagens ópticas obtidas pelo endoscópio são convertidas em fótons e imagens digitais.3,8 As imagens digitais agora podem ser exibidas em monitores externos, uma inovação transformadora para a educação cirúrgica urológica.

Cistouretroscopia

Indicações

A cistoscopia desempenha um papel importante no diagnóstico e tratamento das patologias do trato geniturinário pediátrico. Além disso, as informações anatômicas obtidas por cistouretroscopia facilitam o planejamento da reconstrução geniturinária. As indicações comuns incluem a avaliação de anomalias geniturinárias congênitas (complexo extrofia vesical-epispádias, anomalias cloacais, válvulas uretrais posteriores, ureteres ectópicos), anatomia vaginal e canais urinários, injeção endoscópica para refluxo vesicoureteral e tratamento de cálculos vesicais.9 Praticamente todos os procedimentos são realizados sob anestesia geral na sala de cirurgia. Tabela 1 apresenta as indicações comuns para cistouretroscopia pediátrica. Tabela 2 apresenta intervenções terapêuticas comuns.

Tabela 1 Indicações comuns para cistouretroscopia pediátrica.

| Diagnóstico | Detalhes |

|---|---|

| Anomalias congênitas | Complexo extrofia-epispádia |

| Anomalias cloacais | |

| Ureteres ectópicos | |

| Vaginoscopia para anomalias vaginais | |

| Pielogramas retrógrados para estenoses ureterais, obstrução de UPJ e UVJ | |

| Malignidade | Vigilância do aumento gástrico |

| Avaliação de massa vesical ou uretral | |

| Avaliação de queixas miccionais: hematúria macroscópica, jato fraco, incontinência urinária | |

| CMG para urodinâmica intraoperatória | |

| Avaliação de cirurgia reconstrutiva prévia | Procedimentos no colo vesical |

| Canais urinários |

Tabela 2 Intervenções terapêuticas comuns na cistouretroscopia.

| Tratamento |

|---|

| Válvulas uretrais posteriores |

| Extração de cálculo vesical |

| Injeção endoscópica para RVU, incompetência esfincteriana, incompetência do canal |

| Punção de ureterocele |

| Colocação de cateter suprapúbico ou uretral |

Equipamento

Cistoscópios pediátricos e para adolescentes existem em uma variedade de tamanhos, em modelos flexíveis e rígidos. O tamanho do instrumento é expresso na unidade French (Fr), em que um diâmetro de 1 Fr equivale a 1/3 mm.10 Os componentes do cistoscópio rígido incluem uma lente óptica, ponte, bainha e obturador. As lentes são fabricadas com ângulos de visão variando de 0–120˚. Em nossa prática, as lentes de 0˚ e 30˚ são as mais comuns. A ponte conecta a lente à bainha e fornece 1–2 canais de trabalho. Os tamanhos das bainhas variam de 5 Fr a tamanhos de adulto e têm portas de irrigação associadas. O obturador pode ser usado no lugar da lente dentro da bainha para embotar a ponta da bainha, permitindo a passagem às cegas pela uretra até a bexiga. A cistoscopia rígida também requer uma fonte de luz, câmera endoscópica, monitor externo e fluido de irrigação. Os cistoscópios flexíveis incorporam o endoscópio, a fonte de luz e a câmera em um único aparelho e possuem um único canal de trabalho para irrigação e passagem de instrumentos. As pontas dos cistoscópios flexíveis podem defletir até 210˚, facilitando a manobrabilidade do dispositivo, e estão disponíveis em uma variedade de tamanhos.

Em nossa prática, cistoscópios rígidos são utilizados na maioria dos casos e cistoscópios flexíveis são reservados para casos em que o posicionamento na posição de litotomia é difícil ou para navegação de canais cateterizáveis tortuosos.

Considerações pré-operatórias

A urinálise deve ser realizada antes da instrumentação do trato urinário e, quando aplicável, deve-se realizar cultura de urina.11 A cultura de urina pré-operatória e o tratamento antibiótico, quando indicados, são especialmente importantes em pacientes cujo trato urinário provavelmente está colonizado, como pacientes em cateterização intermitente ou com cateteres permanentes. Se houver infecção do trato urinário, o paciente deve ser tratado com antibióticos específicos guiados pela cultura e o procedimento adiado devido ao risco de bacteremia e sepse.

A Declaração de Melhores Práticas da AUA sobre Procedimentos Urológicos e Profilaxia Antimicrobiana de 2019 desaconselha o uso de antibióticos pré-procedurais para cistoscopia diagnóstica de rotina na ausência de fatores de risco específicos do paciente, como imunocomprometimento, colonização crônica do trato geniturinário, anomalias anatômicas que predispõem à estase urinária e estado nutricional deficiente.12 Não há orientação clara especificamente para instrumentação endourológica pediátrica, mas utilizamos essas diretrizes para orientar a profilaxia antibiótica relacionada ao procedimento. Um histórico cirúrgico detalhado, incluindo revisão de relatórios operatórios, é essencial antes da endoscopia, especialmente no contexto de reconstrução geniturinária prévia.

Considerações Cirúrgicas

Antes da indução da anestesia, os instrumentos endoscópicos devem ser inspecionados quanto à integridade, compatibilidade e funcionamento. Isso é especialmente importante na endoscopia pediátrica, em que são utilizados vários tamanhos de instrumentos e acessórios. Após a indução da anestesia geral e a profilaxia antibiótica pré-procedimento (quando indicada), o paciente é posicionado em litotomia dorsal (Figura 1). Em lactentes, pequenas toalhas enroladas ou rolos de gel podem ser colocados sob os joelhos e as pernas são fixadas no lugar com fita adesiva. Crianças maiores são posicionadas usando perneiras. Genitália e períneo são preparados com solução antisséptica contendo betadine, uma vez que preparações à base de álcool e clorexidina podem danificar as mucosas. A anatomia externa é examinada. Estenose meatal leve pode ser tratada com dilatação sequencial com velas de McCrae, ao passo que estenose meatal grave pode requerer meatotomia formal. Em seguida, um cistoscópio lubrificado é introduzido na uretra e a irrigação é acionada. Em pacientes do sexo masculino, o pênis é tracionado e direcionado superiormente. Essa posição é ideal para a uretroscopia da uretra anterior; em seguida, a mão do cirurgião é abaixada inferiormente para permitir a passagem para a uretra posterior e a bexiga. Realiza-se uma avaliação sistemática da bexiga, quaisquer intervenções auxiliares são realizadas, e a uretra é visualizada com entrada ativa de irrigação durante a retirada do cistoscópio. Observe que a inspeção da bexiga aumentada pode ser difícil devido a dobras da mucosa e à produção de muco. A irrigação para remover o muco da bexiga e o uso criterioso da irrigação podem melhorar a visualização. Deve-se evitar a sobredistensão da bexiga aumentada, pois isso pode levar à perfuração vesical. O cistoscópio flexível é introduzido pela uretra de modo semelhante a um cateter uretral, e a ponta é defletida conforme necessário para visualização e inspeção ao entrar na bexiga.

Figura 1 Litotomia dorsal modificada. Posicionamento cuidadoso na posição de litotomia dorsal modificada em um paciente com osteogênese imperfeita para extração ureteroscópica de cálculo.

A cistoscopia também pode ser realizada pelo trajeto da sonda suprapúbica, pela vesicostomia ou por um conduto cateterizável com técnica semelhante. É importante observar detalhes cirúrgicos (p. ex., tipo de segmento entérico utilizado, trajeto do conduto, mecanismo de continência) antes da endoscopia. Os condutos cateterizáveis são delicados, e o cistoscópio não deve ser avançado antes que o lúmen seja visualizado, para evitar lesão ou perfuração do conduto.

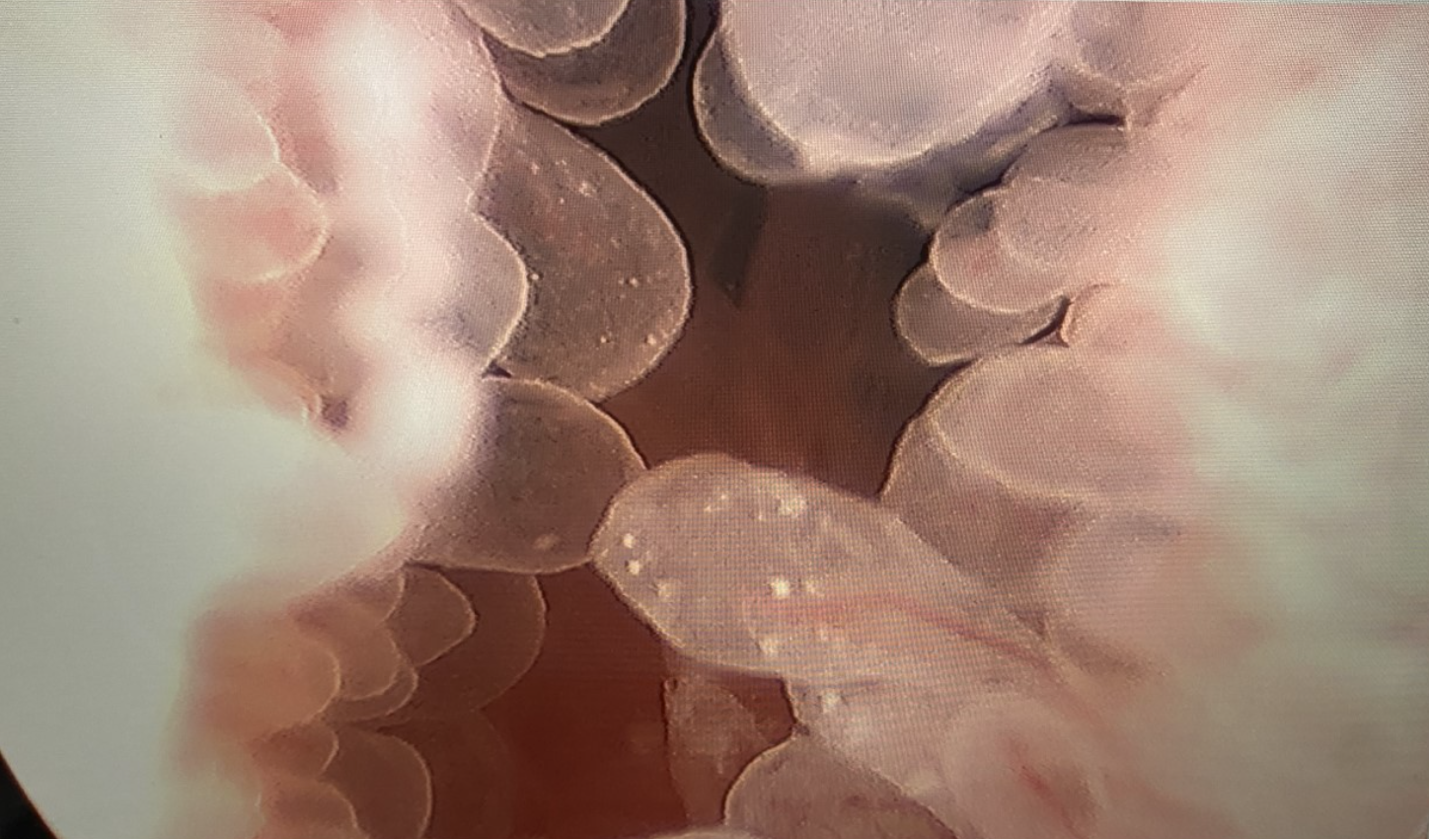

Figura 2 Cistoscopia com Ressecção Transuretral de Tumor de Bexiga. Ressecção transuretral de uma massa papilar no colo vesical em um adolescente do sexo masculino com cistite eosinofílica.

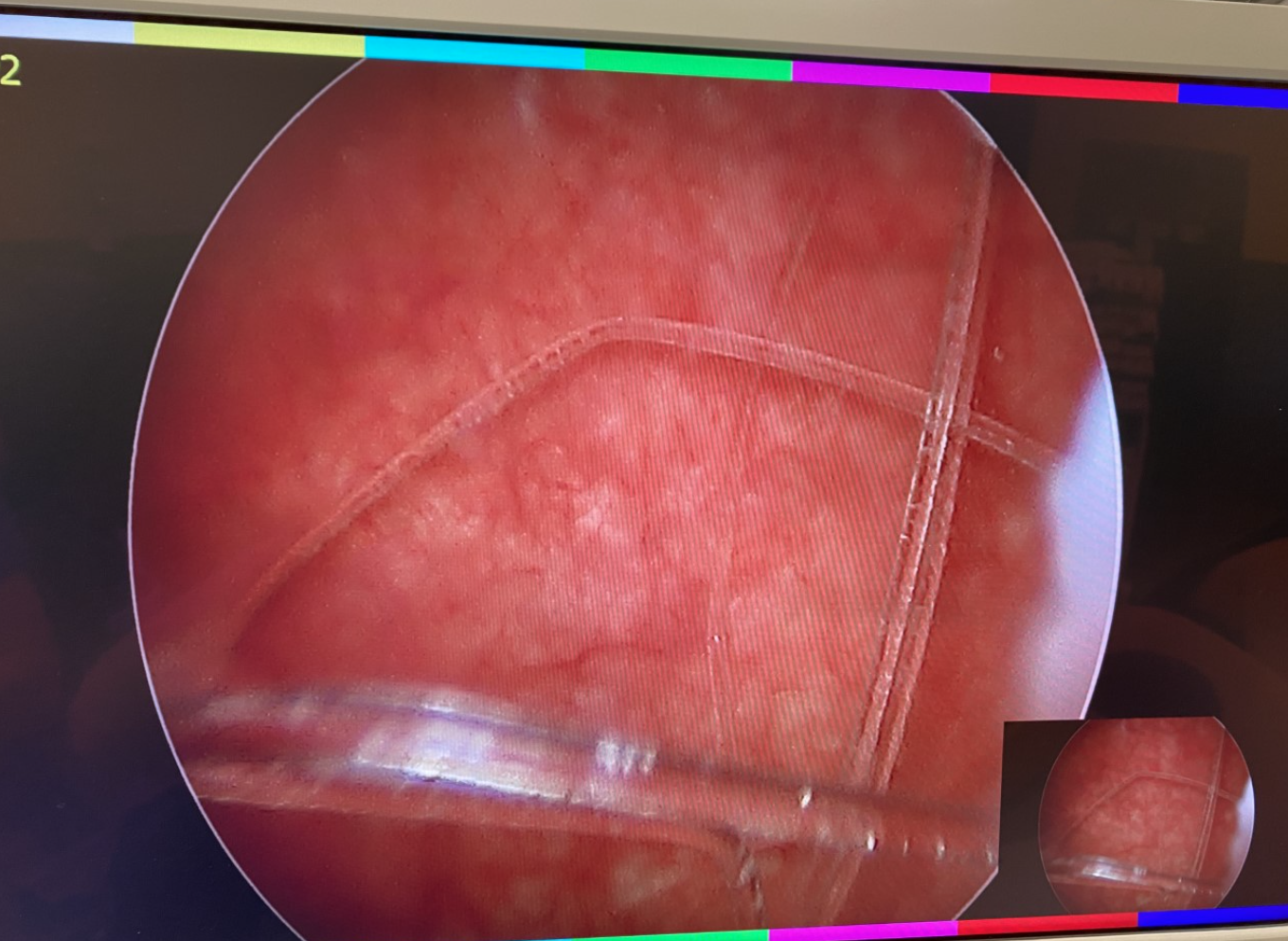

Figura 3 Corpo estranho da bexiga. Cistoscopia com extração com cesta de um corpo estranho da bexiga.

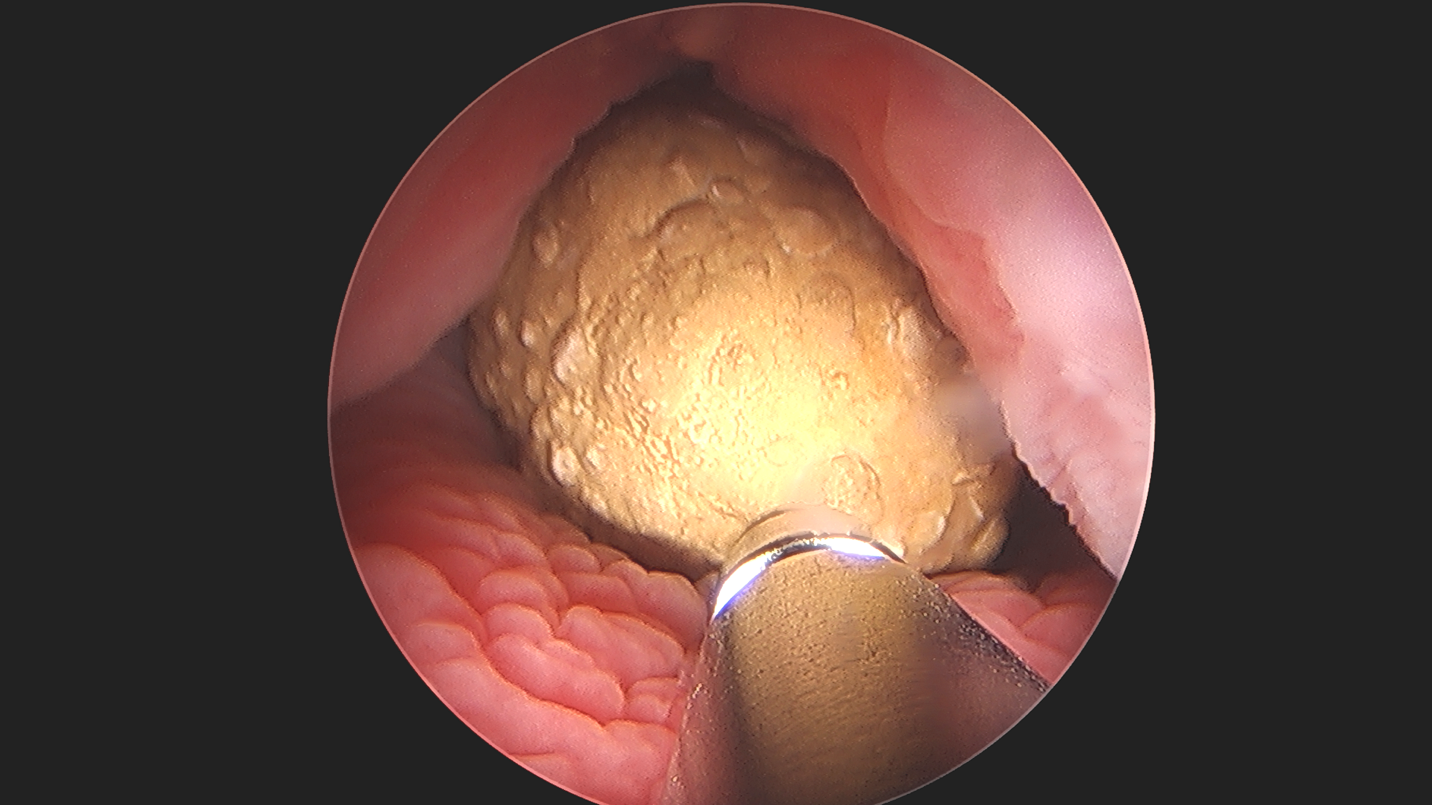

Figura 4 Cistolitotomia percutânea. Litotripsia ultrassônica de cálculo vesical grande em bexiga ampliada, demonstrando a aplicabilidade e a versatilidade da endoscopia.

Complicações

As complicações após a cistouretroscopia diagnóstica são raras e incluem bacteriúria assintomática (5–8%), infecção do trato urinário sintomática (2–5%) e hematúria macroscópica.13

Cuidados Pós-operatórios e Seguimento

A cistouretroscopia é tipicamente um procedimento cirúrgico ambulatorial e causa desconforto mínimo ou nenhum nos pacientes. Salvo contraindicação, sempre aplicamos anestésicos tópicos ao final da cistouretroscopia (por exemplo, gel de lidocaína). Não prescrevemos antibióticos no pós-operatório, a menos que o paciente apresente fatores de risco para urossepsia e seja realizado um tratamento endoscópico.12 A profilaxia antibiótica contínua para refluxo vesicoureteral é mantida até o seguimento ambulatorial após a injeção endoscópica. Disúria ou outros sintomas de armazenamento do trato urinário inferior são tratados com paracetamol ou anti-inflamatórios não esteroidais e anticolinérgicos, se necessário. O seguimento é determinado pelo diagnóstico do paciente e pela intervenção realizada.

Ureteroscopia

Indicações

A ureteroscopia proporciona acesso ao trato urinário superior para fins diagnósticos e terapêuticos. Melhorias na ótica e a miniaturização dos ureteroscópios permitem que cálculos ureterais e renais anteriormente tratados com litotripsia por ondas de choque sejam manejados por via ureteroscópica.14 As Diretrizes de 2016 da AUA/Endourology Society sobre o manejo cirúrgico dos cálculos descrevem a ureteroscopia como uma opção para pacientes pediátricos com carga total de cálculos renais de ≤ 20 mm.15 Indicações adicionais incluem incisão a laser para estenoses ureterais curtas, endopielotomia para obstrução recorrente da junção ureteropélvica (em casos selecionados) e avaliação de hematúria macroscópica lateralizada e defeitos de enchimento ureterais.

Equipamento

Os ureteroscópios estão disponíveis em modelos flexíveis e semirrígidos digitais e de fibra óptica com uma variedade de tamanhos variando de 4.5–11 Fr.16 Ureteroscópios semirrígidos são menores, pois as fibras ópticas estão incorporadas ao endoscópio e requerem uma fonte de luz externa e uma câmera. Dois canais, um usado para irrigação e o outro para passagem de instrumentos, melhoram a visualização. Ureteroscópios semirrígidos são usados no ureter distal aos vasos ilíacos.17 Microureteroscópios, como o ureteroscópio semirrígido Ultrathin de 4.5 Fr (Richard Wolf, Knittlingen, Alemanha), reduzem a falha de acesso em ureteres pediátricos de pequeno calibre.18 Ureteroscópios flexíveis incorporam um sistema óptico, mecanismo de deflexão e canal de trabalho. Modelos digitais incluem a fonte de luz e a câmera embutidas no endoscópio, enquanto modelos de fibra óptica requerem uma câmera e uma fonte de luz externas. A deflexão da ponta distal de até 270˚ permite a navegação por ureteres tortuosos e pela pelve renal e cálices.19 O ureteroscópio flexível é preferido para uso no ureter proximal aos vasos ilíacos e na pelve renal e nos cálices renais. O mecanismo de deflexão do ureteroscópio flexível é delicado e pode ser danificado com o uso repetido. Seu canal de trabalho pode sofrer danos pela passagem de instrumentos ou disparo inadvertido de laser dentro do endoscópio, levando a falha do dispositivo.11 Assim, ureteroscópios flexíveis de uso único vêm ganhando popularidade, pois demonstram eficácia semelhante à dos ureteroscópios flexíveis convencionais e podem oferecer economia de custos.20 No momento, seu papel no paciente pediátrico permanece a ser elucidado.

A ureteroscopia deve ser realizada em uma sala de endoscopia bem equipada com todos os materiais necessários, fluoroscopia e equipe experiente do centro cirúrgico. O equipamento básico necessário para a ureteroscopia inclui endoscópios (semirrígidos e flexíveis), um laser de hólmio e fibras de laser, fios-guia, cateteres ureterais de ponta aberta, cateteres de duplo lúmen, dilatadores coaxiais, bainhas de acesso ureteral, cestas e stents ureterais. Uma variedade de tamanhos de instrumentos descartáveis deve estar disponível e ser adaptada ao tamanho da criança.

Considerações pré-operatórias

Deve-se realizar uma cultura de urina antes da instrumentação do trato urinário. Se houver infecção do trato urinário ou colonização bacteriana crônica, o paciente deve ser tratado com antibióticos específicos conforme a cultura e o procedimento adiado devido ao risco de bacteremia e sepse.11 A Declaração de Melhores Práticas da AUA sobre Procedimentos Urológicos e Profilaxia Antimicrobiana em 2019 recomenda uma dose única de TMP-SMX no perioperatório ou uma cefalosporina de 1a ou 2a geração para procedimentos ureteroscópicos.12 Embora não exista uma diretriz específica para pacientes pediátricos, é nossa prática utilizar cefazolina com ou sem gentamicina antes da ureteroscopia.

Embora o objetivo da ureteroscopia com extração de cálculos seja alcançar a eliminação completa dos cálculos com o menor número possível de procedimentos, vários procedimentos podem ser necessários para tratar com sucesso cálculos ureterais ou renais em crianças. O pequeno calibre dos ureteres pediátricos, especialmente em crianças pequenas, pode dificultar o acesso ureteral direto. Nos casos de falha no acesso, o stent ureteral proporciona dilatação ureteral passiva e pode aumentar a probabilidade de acesso bem-sucedido no futuro. No entanto, o uso rotineiro de stent pré-procedimental não é recomendado.15

Técnica Cirúrgica

Após a indução de anestesia geral e a administração de profilaxia antibiótica orientada por diretrizes, o paciente é posicionado em litotomia dorsal, conforme discutido previamente. Utiliza-se fluido de irrigação com solução salina isotônica aquecido à temperatura corporal, dado o risco de absorção e hiponatremia.11 Um cistoscópio é utilizado para obter acesso ureteral, e realiza-se uma pielografia retrógrada para definir a anatomia do sistema coletor e determinar a localização do cálculo. Coloca-se um fio-guia de segurança (0.025–0.038 polegadas). Um fio-guia de trabalho também pode ser colocado nesse momento, o que permite a passagem de uma bainha de acesso ureteral ou de um ureteroscópio flexível. O ureteroscópio é introduzido no óstio ureteral após hidrodilatação utilizando uma bomba manual de irrigação e é avançado até o cálculo.21 Se o ureteroscópio não passar, coloca-se um stent ureteral para permitir dilatação ureteral passiva por 2–3 semanas antes de repetir a ureteroscopia. Alternativamente, pode-se empregar dilatação ureteral ativa com um cateter de duplo lúmen de 8–10 Fr ou dilatador coaxial, mas a dilatação com balão do óstio ureteral deve ser evitada devido ao risco de estenose ureteral.22 Se o cálculo for grande demais para extração en bloc com cesta, utiliza-se um laser de Hólmio:YAG para tratar o cálculo usando configurações de fragmentação (alta energia, baixa frequência) ou pulverização (baixa energia, alta frequência). Fragmentos de cálculos maiores são extraídos com cesta e enviados para análise do cálculo, e fragmentos menores (< 1mm) são deixados in situ para passagem espontânea. Bainhas de acesso ureteral (9.5–14 Fr) devem ser utilizadas para cálculos ureterais proximais ou renais grandes, pois seu uso demonstrou reduzir as pressões intrarrenais, facilitar múltiplas passagens do endoscópio e proteger o ureter de trauma.23 No entanto, o uso de uma bainha de acesso ureteral nem sempre é viável devido ao pequeno calibre dos ureteres pediátricos. Após a conclusão da litotripsia, pode ser colocado um stent ureteral. A decisão de colocar um stent ureteral baseia-se no tempo operatório, carga litiásica, edema ureteral e trauma durante o procedimento. Em casos selecionados, stents ureterais são colocados com um fio exteriorizado, permitindo remoção sem um segundo procedimento. O uso de raios X durante o procedimento deve seguir o conceito ALARA (as low as reasonably achievable), pois crianças com nefrolitíase frequentemente requerem mais exames de imagem no futuro.24 O uso intermitente de raios X em baixa dose, com distância pele-alvo máxima, janela de imagem estreita e evitando a ampliação, pode reduzir a exposição à radiação do procedimento.25

Complicações

Séries contemporâneas relatam taxas globais de complicações da ureteroscopia variando de 0 a 14% em pacientes pediátricos e incluem infecção do trato urinário, hematúria, cólica renal, hidronefrose pós-operatória e lesão ureteral.18,26,27,28 Complicações mais graves (> Clavien 3) são raras, com avulsão ureteral completa e sepse ocorrendo em <1% dos pacientes.29 Idade mais jovem pode estar associada a um risco aumentado de complicações após procedimentos ureteroscópicos. Uma revisão sistemática de 10 estudos (1.377 procedimentos) demonstrou uma maior taxa de complicações em crianças < 6 anos (24%) em comparação com crianças > 6 anos (7,1%).28

Cuidados pós-operatórios e seguimento

A ureteroscopia é, na maioria dos casos, um procedimento cirúrgico ambulatorial. A dor pós-operatória é tratada com anti-inflamatórios não esteroidais, e o uso de analgésicos opioides é limitado. Um ensaio clínico randomizado, duplo-cego, recente em pacientes adultos demonstrou a não inferioridade de 10mg de cetorolaco em relação a 5mg de oxicodona para o tratamento da dor após ureteroscopia.30 Pacientes com stents ureterais recebem prescrição de anticolinérgicos e bloqueadores alfa, pois seu uso pode reduzir os sintomas associados ao stent ureteral.31,32 A obstrução ureteral silenciosa após ureteroscopia ocorre em até 3% dos pacientes. Portanto, é nossa prática realizar ultrassonografia renal 4 semanas após a ureteroscopia em todos os pacientes.33

Nefroscopia

Indicações

A nefroscopia percutânea com nefrolitotomia é o padrão de tratamento para cálculos renais volumosos e para cálculos em rins com anomalias anatômicas que inviabilizam a litotripsia por ondas de choque ou a cirurgia intrarrenal retrógrada. Historicamente, havia preocupações de que o uso de instrumentos e bainhas de tamanho adulto (24–30 Fr) em rins pediátricos levasse a lesão parenquimatosa e aumentasse o risco de complicações de curto e longo prazos.19 No entanto, com o aprimoramento da técnica e a miniaturização dos nefroscópios, a nefrolitotomia percutânea (PCNL) é considerada segura e eficaz em pacientes pediátricos.34 As Diretrizes de 2016 da AUA/Sociedade de Endourologia sobre o Manejo Cirúrgico dos Cálculos recomendam a PCNL como opção de tratamento para carga litiásica renal total de >20mm.15 Além disso, a PCNL pode ser utilizada para tratar cálculos em divertículos caliciais, em outros rins anatomicamente complexos, ou quando o acesso retrógrado não é factível, como em casos de derivação urinária.

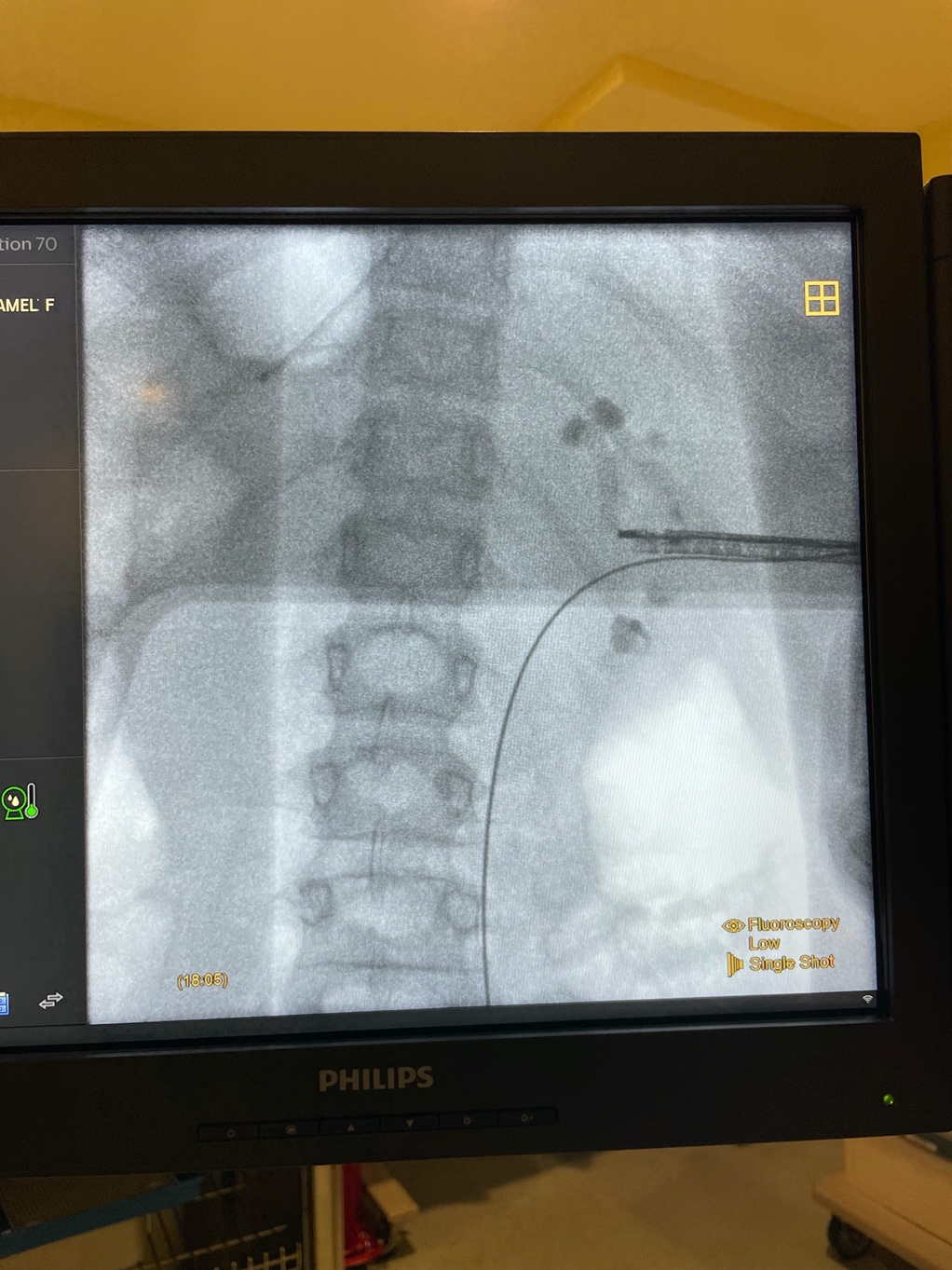

Figura 5 Nefroscopia rígida. Imagem radiográfica durante PCNL de revisão para grandes cálculos renais utilizando nefroscópio rígido com acesso renal médio.

Equipamento

Nefroscópios rígidos permitem a visualização da pelve renal e dos cálices, estão disponíveis em modelos de fibra óptica e digitais e são oferecidos em uma variedade de tamanhos (4,8–24 Fr).16 O modelo com lentes em bastão de fibra óptica requer uma câmera e uma fonte de luz externas, enquanto o modelo digital incorpora o endoscópio, a fonte de luz e a câmera ao dispositivo.35 Um canal de trabalho permite a introdução de instrumentos e as portas de entrada e saída permitem o enchimento e o esvaziamento simultâneos do sistema coletor.

Os litotritores intracorpóreos incluem modelos ultrassônicos, pneumáticos e combinados.35 Uma sucção incorporada de grande calibre remove fragmentos de cálculo e pó durante a litotripsia.

O PCNL padrão envolve o uso de uma bainha Amplatz de 24–30 Fr e instrumentos de tamanho adulto. Dada a preocupação de que o uso de instrumentos de tamanho adulto possa aumentar as taxas de complicações no PCNL pediátrico, foram desenvolvidas técnicas que utilizam instrumentos menores. Mini-PCNL descreve o uso de trajetos de nefrostomia de 15–24 Fr, ultra-mini PCNL com trajetos de 11–15 Fr e micro-PCNL com trajetos < 10 Fr.16 Os procedimentos devem ser realizados em uma sala de cirurgia com pessoal experiente, fluoroscopia e equipamento apropriado em uma variedade de tamanhos. Os instrumentos necessários para PCNL incluem nefroscópios rígidos e flexíveis, dilatadores com balão ou Amplatz, bainhas de acesso, laser de Hólmio:YAG, litotridor pneumático ou ultrassônico, fios-guia, cateteres ureterais, cateteres de lúmen duplo e cestos.

Considerações pré-operatórias

Todos os pacientes considerados para PCNL devem ser submetidos a uma tomografia computadorizada de baixa dose do abdome e pelve para determinar a viabilidade e avaliar a carga litiásica renal total.15 Além disso, as imagens seccionais permitem determinar o cálice mais adequado para o acesso, a proximidade de órgãos adjacentes (cólon, pleura, costelas) e alterações na anatomia renal.

Deve ser realizada uma urocultura pré-operatória, e todos os pacientes com infecção do trato urinário devem ser tratados com antibióticos específicos guiados pela cultura antes do procedimento. É importante notar que uma cultura do trato urinário inferior pode não refletir as culturas do cálculo ou da urina do trato superior. A Declaração de Melhores Práticas da AUA de 2019 sobre Procedimentos Urológicos e Profilaxia Antimicrobiana recomenda as seguintes opções de antibióticos antes da PCNL com base em literatura de alta qualidade em pacientes adultos: cefalosporina de 1ª/2ª geração, aminoglicosídeo e metronidazol, aztreonam e metronidazol, aminoglicosídeo e clindamicina ou aztreonam e clindamicina.12 A literatura sobre profilaxia antibiótica pré-operatória prévia à PCNL em pacientes pediátricos é limitada. Uma revisão retrospectiva de 830 crianças com idade < 12 anos examinou a taxa de infecção do trato urinário febril após a PCNL. Cefalosporinas de primeira, segunda e terceira geração foram consideradas igualmente eficazes para profilaxia em crianças < 12 submetidas à PCNL.36 Nossa prática é usar cefazolina e gentamicina como profilaxia antibiótica antes da PCNL.

Considerações Cirúrgicas

Após indução de anestesia geral e administração de antibióticos intravenosos, o paciente é posicionado em decúbito ventral sobre rolos de gel. O acesso percutâneo ao cálice desejado é realizado sob orientação fluoroscópica ou ultrassonográfica. Alternativamente, a radiologia intervencionista pode obter acesso percutâneo guiado por TC em casos de anatomia aberrante ou disrafismo espinhal. Podem ser necessários múltiplos acessos para o tratamento de cálculos coraliformes parciais ou completos. Um fio-guia de trabalho e um fio-guia de segurança são posicionados, a pele é incisada e o trajeto é dilatado com balão ou dilatadores de Amplatz, de acordo com a preferência do cirurgião. A escolha do dilatador e do calibre da bainha baseia-se na idade do paciente, habitus corporal, anatomia, carga litiásica e calibre do nefroscópio disponível. Observe que os rins pediátricos são mais móveis do que os rins de adultos e podem se afastar durante a dilatação ou o avanço da bainha.37 Em seguida, a bainha é introduzida sobre o dilatador até o sistema coletor. Encurtar a bainha pode melhorar a manobrabilidade. Utiliza-se solução isotônica aquecida, dada a propensão à hipotermia e à hipervolemia. O nefroscópio rígido é avançado até o cálculo e inicia-se a fragmentação, utilizando laser de hólmio:YAG ou litotridor. Fragmentos do cálculo são extraídos e enviados para análise litiásica e cultura. Um cistoscópio flexível ou ureteroscópio é utilizado para realizar nefroscopia flexível e extrair fragmentos residuais do cálculo. Após a remoção da carga litiásica, pode-se posicionar um cateter de nefrostomia percutânea, um stent ureteral ou ambos. Essa decisão baseia-se na complexidade cirúrgica, na carga litiásica residual, na necessidade de procedimento de revisão e na preferência do cirurgião.38 Recomendamos limitar o tempo operatório a 90 minutos, pois tempos operatórios prolongados aumentam o risco de ITU febril no pós-operatório.36

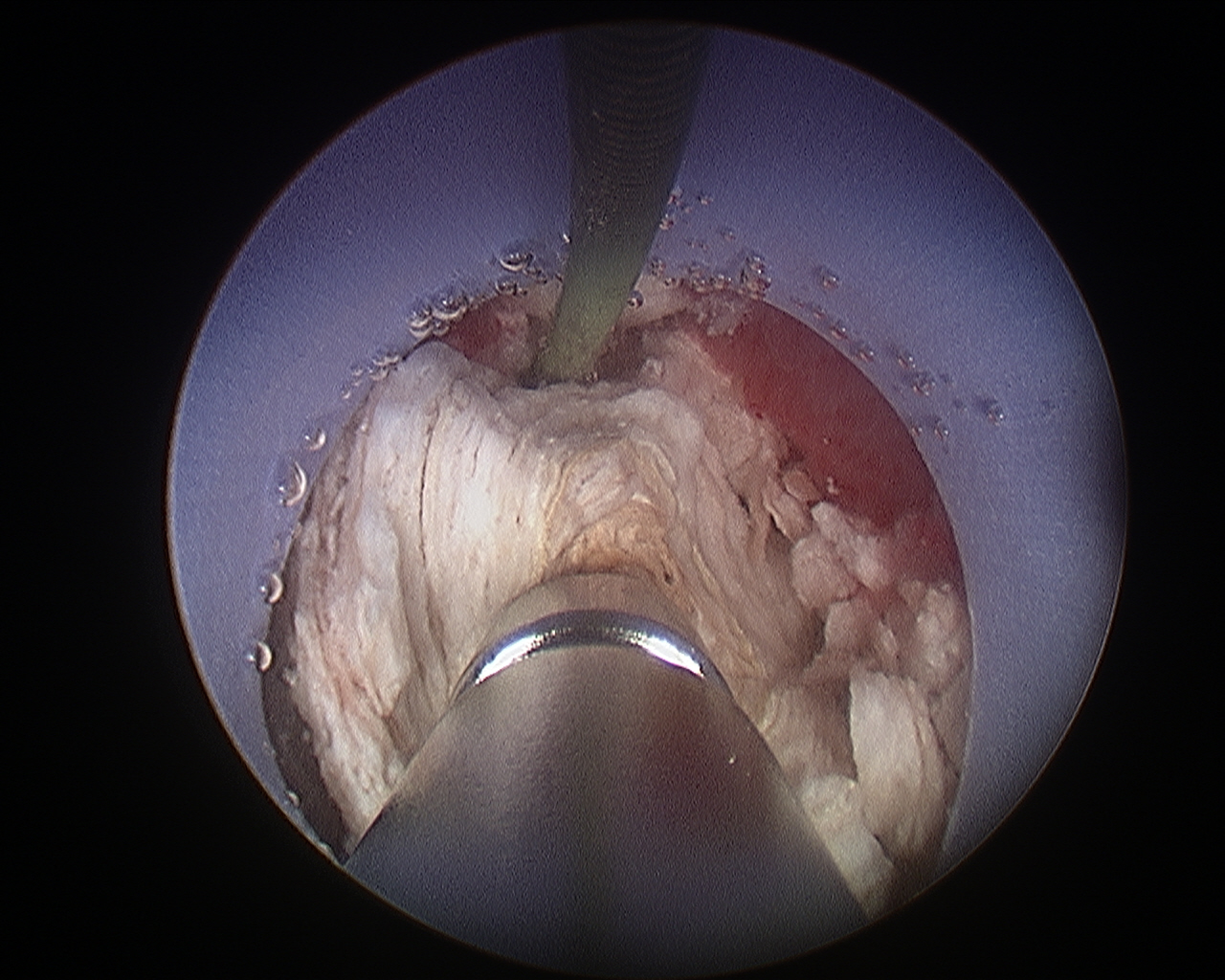

Figura 6 Nefrolitotomia percutânea. Litotripsia ultrassônica de um grande cálculo renal durante nefrolitotomia percutânea.

Complicações

Séries contemporâneas relatam taxas de complicações após PCNL pediátrica de 11–40%.34,39 As complicações mais comuns são infecção do trato urinário febril e sangramento que requer transfusão.34,39 Complicações graves, como sangramento maciço, extravasamento de urina que requer drenagem, lesão visceral (cólon, pleura), lesão da pelve renal e hidrotórax, são raras, com 84% das complicações < grau III de Clavien.34,39 O tamanho do cálculo, a complexidade do caso e o tempo operatório estão associados às taxas de complicações.34,40 PCNL ultra-mini e micro, utilizando trajetos de acesso menores, apresentam menores taxas globais de complicações (11.2%).41

Cuidados pós-operatórios e acompanhamento

Após a PCNL, os pacientes permanecem internados por 2–5 dias. Os antibióticos perioperatórios são mantidos por 24 horas após a cirurgia. São realizados exames laboratoriais para avaliar anormalidades eletrolíticas e/ou perda sanguínea significativa. São obtidos exames de imagem pós-operatórios para avaliar a carga litiásica residual e planejar tratamento cirúrgico adicional. Se não houver PCNL de revisão planejada e a hematúria macroscópica tiver cessado, o cateter de nefrostomia é removido antes da alta hospitalar. Frequentemente, são necessários procedimentos adicionais para alcançar remoção completa dos cálculos. As taxas de ausência de cálculos após a PCNL variam de 63–85.4% e aumentam para 91.7–93.7% com tratamento subsequente (PCNL de revisão, litotripsia por ondas de choque, cirurgia intrarrenal retrógrada).34,42,43

Conclusões

Os avanços tecnológicos nos equipamentos endoscópicos transformaram o campo da urologia pediátrica, ampliando o potencial diagnóstico e terapêutico. Condições anteriormente tratadas com procedimentos cirúrgicos abertos agora são abordadas por via endoscópica. À medida que a inovação em dispositivos avança a uma taxa exponencial, estudos prospectivos de alta qualidade também devem acompanhar para elucidar o papel dessa nova tecnologia no arsenal terapêutico do urologista pediátrico.

Pontos-chave

- A miniaturização de instrumentos endoscópicos para adultos e as melhorias na tecnologia levaram ao desenvolvimento de cistoscópios, ureteroscópios e nefroscópios pediátricos

- A escolha do tipo e do tamanho do endoscópio deve ser adaptada à idade, ao tamanho, ao habitus corporal e à anatomia específica da criança

- A profilaxia antibiótica pré-procedimento de rotina não é recomendada para cistoscopia não complicada, mas é indicada para instrumentação do trato urinário superior

- Ao realizar endoscopia pediátrica, devemos seguir o conceito ALARA para limitar a exposição à radiação do procedimento

- A remoção completa dos cálculos com ureteroscopia ou PCNL pode exigir múltiplos procedimentos, dado o pequeno calibre do sistema coletor e do ureter pediátricos

Recursos para Pacientes

- https://www.urologyhealth.org/healthy-living/urologyhealth-extra/magazine-archives/summer-2020/kidney-stones-in-children

- https://pedsnet.org/pkids/

Leituras recomendadas

- Tekgül S, Stein R, Bogaert G, Nijman RJM, Quaedackers J, Hoen L ’t, et al.. European Association of Urology and European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines on Paediatric Urinary Stone Disease. Eur Urol Focus 2021; 8 (3): 833–839. DOI: 10.1016/j.euf.2021.05.006.

- Kokorowski PJ, Chow JS, K S. Prospective Measurement of Patient Exposure to Radiation During Pediatric Ureteroscopy. Yearbook of Urology 2012; 2012 (4): 224–225. DOI: 10.1016/j.yuro.2012.07.025.

- Duty B, Conlin M. Principles of Urologic Endoscopy. In: Partin A, editor. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021. DOI: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60891-x.

Referências

- REUTER MATTHIASA, REUTER HANSJ. The Development Of The Cystoscope. J Urol 1998; 59 (3): 638–640. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63691-7.

- Shah J. Endoscopy through the ages. BJU Int 2002; 89 (7): 645–652. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02726.x.

- Samplaski MK, Jones JS. Two centuries of cystoscopy: the development of imaging, instrumentation and synergistic technologies. BJU Int 2009; 103 (2): 154–158. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.08244.x.

- Talwar HS. The journey of the “Lichtleiter”, the first ever cystoscope: An ode to Philipp Bozzini and his great invention. Eur Urol 1969; 81: S751. DOI: 10.1016/s0302-2838(22)00581-4.

- Nicholson P. Problems encountered by early endoscopists. Urology 1982; 19 (1): 114–119. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(82)90065-6.

- Herr HW. Max Nitze, the Cystoscope and Urology. J Urol 2006; 176 (4): 1313–1316. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.06.085.

- Sasian J. Harold H. Hopkins. Introduction to Aberrations in Optical Imaging Systems 1998; 2 (1): xvii–xviii. DOI: 10.1017/cbo9780511795183.

- Berci G, Paz-Partlow M. Electronic imaging in endoscopy. Surg Endosc 1988; 2 (4): 227–233. DOI: 10.1007/bf00705327.

- Gobbi D, Midrio P, Gamba P. Instrumentation for minimally invasive surgery in pediatric urology. Transl Pediatr 2015; 5 (4): 186–204. DOI: 10.21037/tp.2016.10.07.

- Osborn NK, Baron TH. The history of the “French” gauge. Gastrointest Endosc 2006; 63 (3): 461–462. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.019.

- Duty B, Conlin M. Principles of Urologic Endoscopy. In: Partin A, editor. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021. DOI: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60891-x.

- Lightner DJ, Wymer K, Sanchez J, Kavoussi L. Best Practice Statement on Urologic Procedures and Antimicrobial Prophylaxis. J Urol 2020; 203 (2): 351–356. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000000509.

- TURAN HALE, BALCI UGUR, ERDINC FSEBNEM, TULEK NECLA, GERMIYANOGLU CANKON. Bacteriuria, pyuria and bacteremia frequency following outpatient cystoscopy. Int J Urol 2006; 13 (1): 25–28. DOI: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01219.x.

- Salerno A, Nappo SG, Matarazzo E, De Dominicis M, Caione P. Treatment of pediatric renal stones in a Western country: A changing pattern. J Pediatr Surg 2013; 48 (4): 835–839. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2012.09.058.

- Assimos D, Krambeck A, NL M. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Surgical management of stones: american urological association/endourological society guideline, PART I. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2016; 96 (4): 161–169. DOI: 10.3410/f.726388210.793519339.

- Silay MS. Recent Advances in the Surgical Treatment of Pediatric Stone Disease Management. European Urology Supplements 2017; 16 (8): 182–188. DOI: 10.1016/j.eursup.2017.07.002.

- Payne DA KJFX. Rigid and flexible ureteroscopes: technical features. In: Smith AD, Badlani GH, Preminger GM, Kavoussi LR, editors. Smith’s Textbook of Endourology. 3rd ed. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell;2012:365-87; . DOI: 10.1002/9781444345148.ch34.

- Kucukdurmaz F, Efe E, Sahinkanat T, Amasyalı AS, Resim S. Ureteroscopy With Holmium:Yag Laser Lithotripsy for Ureteral Stones in Preschool Children: Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Complications and Success. Urology 2018; 111: 162–167. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2017.09.006.

- Tasian GE, Copelovitch LA. Management of pediatric kidney stone disease. In: Partin A, editor. Campbell-Walsh-Wein Urology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s11934-007-0067-8.

- Davis NF, Quinlan MR, Browne C, Bhatt NR, Manecksha RP, D’Arcy FT, et al.. Single-use flexible ureteropyeloscopy: a systematic review. World J Urol 2018; 36 (4): 529–536. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-017-2131-4.

- Soygur T, Zumrutbas AE, Gulpinar O, Suer E, Arikan N. Hydrodilation of the Ureteral Orifice in Children Renders Ureteroscopic Access Possible Without any Further Active Dilation. J Urol 2006; 176 (1): 285–287. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(06)00580-5.

- MINEVICH EUGENE, DeFOOR WILLIAM, REDDY PRAMOD, NISHINAKA KAZUYUKI, WACKSMAN JEFFREY, SHELDON CURTIS, et al.. Ureteroscopy Is Safe And Effective In Prepubertal Children. J Urol 2005; 174 (1): 276–279. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161212.69078.e6.

- Auge BK, Pietrow PK, Lallas CD, Raj GV, Santa-Cruz RW, Preminger GM. Ureteral Access Sheath Provides Protection against Elevated Renal Pressures during Routine Flexible Ureteroscopic Stone Manipulation. J Endourol 2004; 18 (1): 33–36. DOI: 10.1089/089277904322836631.

- Kuhns LR, Oliver WJ, Christodoulou E, Goodsitt MM. The Predicted Increased Cancer Risk Associated With a Single Computed Tomography Examination for Calculus Detection in Pediatric Patients Compared With the Natural Cancer Incidence. Pediatr Emerg Care 2011; 27 (4): 345–350. DOI: 10.1097/pec.0b013e3182132016.

- Kokorowski PJ, Chow JS, K S. Prospective Measurement of Patient Exposure to Radiation During Pediatric Ureteroscopy. Yearbook of Urology 2012; 2012 (4): 224–225. DOI: 10.1016/j.yuro.2012.07.025.

- Tolga-Gulpinar M, Resorlu B, Atis G, Tepeler A, Ozyuvali E, Oztuna D, et al.. Safety and efficacy of retrograde intrarenal surgery in patients of different age groups. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed) 2015; 39 (6): 354–359. DOI: 10.1016/j.acuroe.2015.05.005.

- Dogan HS, Onal B, N S. Factors Affecting Complication Rates of Ureteroscopic Lithotripsy in Children: Results of Multi-Institutional Retrospective Analysis by Pediatric Stone Disease Study Group of Turkish Pediatric Urology Society. J Urol 2011; 186 (3): 1035–1040. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.04.097.

- Ishii H, Griffin S, Somani BK. Flexible ureteroscopy and lasertripsy (FURSL) for paediatric renal calculi: Results from a systematic review. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 11 (3): 164. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.01.010.

- De Coninck V, Keller EX, Somani B, Giusti G, Proietti S, Rodriguez-Socarras M, et al.. Complications of ureteroscopy: a complete overview. World J Urol 2020; 38 (9): 2147–2166. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-019-03012-1.

- Fedrigon D, Faris A, N K. SKOPE–Study of Ketorolac vs Opioid for Pain after Endoscopy: A Double-Blinded Randomized Control Trial in Patients Undergoing Ureteroscopy. Reply. J Urol 2021; 206 (6): 1529–1530. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000002194.

- Zhou L, Cai X, Li H, Wang K-jie. Effects of \ensuremathα-Blockers, Antimuscarinics, or Combination Therapy in Relieving Ureteral Stent-Related Symptoms: A Meta-Analysis. J Endourol 2015; 29 (6): 650–656. DOI: 10.1089/end.2014.0715.

- Sivalingam S, Streeper NM, Sehgal PD, Sninsky BC, Best SL, Nakada SY. Does Combination Therapy with Tamsulosin and Tolterodine Improve Ureteral Stent Discomfort Compared with Tamsulosin Alone? A Double-Blind, Randomized, Controlled Trial. J Urol 2016; 195 (2): 385–390. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2015.08.104.

- Weizer AZ, Auge BK, Silverstein AD, Delvecchio FC, Brizuela RM, Dahm P, et al.. Routine Postoperative Imaging is Important After Ureteroscopic Stone Manipulation. J Urol 2002; 68 (2): 46–50. DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64829-X.

- Goyal NK, Goel A, Sankhwar SN, Singh V, Singh BP, Sinha RJ, et al.. A critical appraisal of complications of percutaneous nephrolithotomy in paediatric patients using adult instruments. BJU Int 2014; 113 (5): 801–810. DOI: 10.1111/bju.12506.

- Canales BK, Pugh JW. New instrumentation in percutaneous nephrolithotomy. Indian J Urol 2010; 26 (3): 389. DOI: 10.4103/0970-1591.70579.

- Kaygısız O, Satar N, Güneş A, Doğan HS, Erözenci A, Özden E, et al.. Factors predicting postoperative febrile urinary tract infection following percutaneous nephrolithotomy in prepubertal children. J Pediatr Urol 2018; 14 (5): 448.e1–448.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.04.010.

- Tekgül S, Stein R, Bogaert G, Nijman RJM, Quaedackers J, Hoen L ’t, et al.. European Association of Urology and European Society for Paediatric Urology Guidelines on Paediatric Urinary Stone Disease. Eur Urol Focus 2021; 8 (3): 833–839. DOI: 10.1016/j.euf.2021.05.006.

- Aghamir SMK, Salavati A, Aloosh M, Farahmand H, Meysamie A, Pourmand G. Feasibility of Totally Tubeless Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Under the Age of 14 Years: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Endourol 2012; 26 (6): 621–624. DOI: 10.1089/end.2011.0547.

- Hosseini MM, Irani D, Altofeyli A, Eslahi A, Basiratnia M, Haghpanah A, et al.. Outcome of Mini-Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in Patients Under the Age of 18: An Experience With 112 Cases. Front Surg 2021; 8 (613812). DOI: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.613812.

- Nouralizadeh A, Basiri A, Javaherforooshzadeh A, Soltani MH, Tajali F. Experience of percutaneous nephrolithotomy using adult-size instruments in children less than 5 years old. J Pediatr Urol 2009; 5 (5): 351–354. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2008.12.009.

- Çitamak B, Dogan HS, Ceylan T, Hazir B, Bilen CY, Sahin A, et al.. A new simple scoring system for prediction of success and complication rates in pediatric percutaneous nephrolithotomy: stone-kidney size score. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (1): 67.e1–67.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.09.019.

- Baydilli N, Tosun H, Akınsal EC, Gölbaşı A, Yel S, Demirci D. Effectiveness and complications of mini-percutaneous nephrolithotomy in children: one center experience with 232 kidney units. Turk J Urol 2019; 46 (1): 69–75. DOI: 10.5152/tud.2019.19158.

- Jones P, Bennett G, Aboumarzouk OM, Griffin S, Somani BK. Role of Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy Techniques–Micro and Ultra-Mini PCNL (<15F) in the Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review. J Endourol 2017; 31 (9): 816–824. DOI: 10.1089/end.2017.0136.

- Xue W, Pacik D, Boellaard W, Breda A, Botoca M, Rassweiler J, et al.. Management of Single Large Nonstaghorn Renal Stones in the CROES PCNL Global Study. J Urol 2012; 187 (4): 1293–1297. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.11.113.

- Unsal A, Resorlu B, Kara C, Bozkurt OF, Ozyuvali E. Safety and Efficacy of Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy in Infants, Preschool Age, and Older Children With Different Sizes of Instruments. Urology 2010; 76 (1): 247–252. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.08.087.

Ultima atualização: 2025-09-21 13:35