5: Prenatal Diagnosis and Antenatal Surgery

Este capítulo levará aproximadamente 23 minutos para ler.

Introduction

A second trimester comprehensive fetal anatomic survey has become standard prenatal care. Prenatal ultrasound detects 84.4–97% of all fetal urinary tract malformations and these anomalies may be detected as early as 12–14 weeks of gestation.1,2 Prior to routine antenatal screening, symptomatic children with urologic abnormalities were detected after birth, presenting with such symptoms as urosepsis, pain, hematuria, a palpable mass or failure to thrive, often requiring surgical intervention. The advent of routine prenatal ultrasonography has shifted the scope of pediatric urologic care from an interventional/surgical model to an antenatal counseling role.

Antenatal hydronephrosis is seen in 1–5% of all pregnancies and represents the most frequent prenatal diagnosis.3 The majority of these patients have mild renal pelvis dilation that spontaneously resolves; however, hydronephrosis may be secondary to obstruction of the urinary tract, which may or may not benefit from prenatal intervention. As such, a comprehensive knowledge of the pathophysiology of potential urinary tract malformations which may be detected via antenatal screening and their possible prenatal manifestations and intervention is required.

Embryology

Renal Embryology

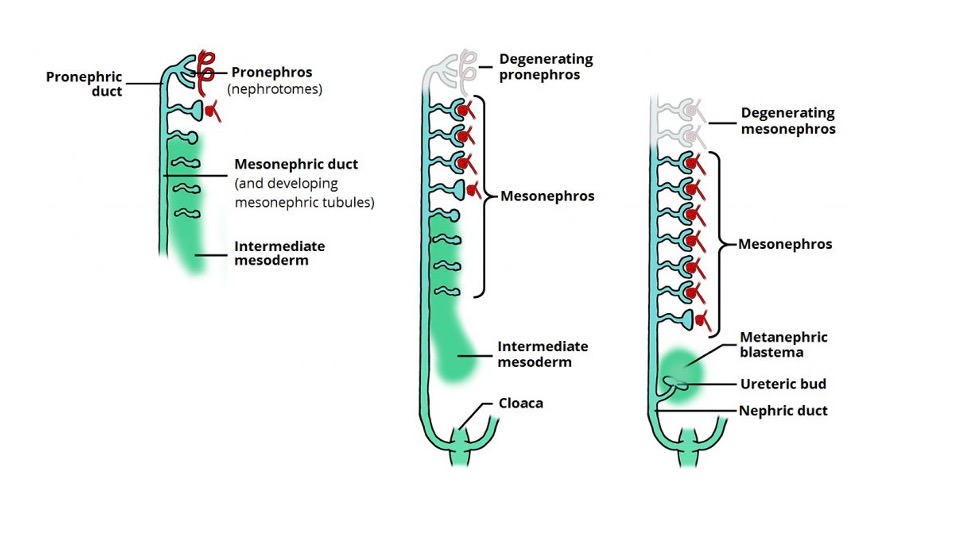

The urinary and genital tracts arise from the intermediate mesoderm. At the fourth week following conception, the mesonephros is formed from two elongated swellings of mesoderm. This rudimentary system temporarily produces urine between 6 and 10 weeks of gestation and will then regress. At 5–6 weeks of gestation, the ureteric bud originates from an outpouching of the mesonephric (Wolffian) duct. The ureteric bud grows cephalad and penetrates the metanephric blastema in week 7. This results in tissue induction of the undifferentiated mesenchyme, transforming it into functioning nephrons of the metanephric kidney (Figure 1) The interaction between the ureteric bud and metanephric blastema is crucial for the creation of functional kidneys and without this occurrence renal agenesis occurs.

Figure 1 The sequential development and degeneration of the pronephros and mesonephros and induction of the ureteric bud and metanephric blastema leading to kidney development. Image obtained from Teach Me Anatomy.

The renal cortex and nephrons develop from the metanephric blastema and the collecting tubules, papillary ducts, calyces, and renal pelvis, and the ureter arises from the ureteric bud. The ureter forms a solid cord of tissue by the sixth week of gestation and undergoes canalization, beginning at the mid-ureteral segment and extending bidirectionally. The ureteropelvic junction and the ureterovesical junction are the last segments to canalize. The membrane that develops during canalization, called Chwalla’s membrane, may contribute to transient/physiologic hydronephrosis and hydroureteronephrosis if there is a delay in its perforation.4 During the tenth week, the nephrons connect to the collecting duct and urine production begins. If the nephrons and collecting system do not join properly, an early obstructive process may occur, which may result in development of a multicystic dysplastic kidney.5

During the sixth to ninth weeks of gestation, the kidneys ascend to their final location in the lumbar region. Renal ectopia occurs when the kidneys fail to migrate, with the pelvis being the most common ectopic location. In addition, fusion of the lower poles of the kidneys may result in a horseshoe kidney. With a horseshoe kidney, ascent into the abdomen is restricted by the inferior mesenteric artery, resulting in its ectopic location. A video depicting normal prenatal kidney development is available (Video 1).

Video 1. Depiction of normal prenatal kidney development.

By the tenth week of gestation, the nephron is mature and urine production begins. The kidneys are able to remove sodium and concentrate urea by the 12th to 14th week of gestation and after 18 weeks of intrauterine life, nearly all of the amniotic fluid is fetal urine. This ability of the kidneys to make urine and maintain adequate amniotic fluid volumes has a profound influence on the growth and development of the fetus and plays a key role on fetal lung development.

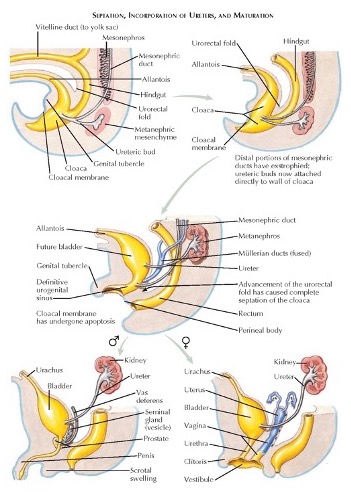

Bladder Embryology

The development of the anterior abdominal wall, bladder and urorectal septum are also interrelated. At the fifth to sixth week of gestation, the urorectal septum first divides the cloaca into the dorsal anorectal canal and the ventral urogenital sinus. Abnormalities of the cloacal membrane lead to anorectal malformations. The urogenital sinus forms the bladder and urethra and the allantois is the embryonic precursor of the urachal remnant.

The mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts fuse with the cloaca just prior its subdivision into the urorectal septum. The entrance of the mesonephric ducts distinguishes the cephalad vesicourethral canal from the caudal urogenital sinus. The vesicourethral canal forms the bladder and pelvic urethra. The caudal portion of the urogenital sinus forms the phallic urethra in males and the urethral and vaginal vestibules in females. These normal divisions of the cloaca are depicted in (Figure 2) A detailed video describing normal bladder development is available (Video 2).

Figure 2 Normal embryologic division of the cloaca and development of the genitourinary system.

Video 2. Description of normal bladder development.

The cloacal membrane originally defines the ventral wall of the urogenital septum. As the membrane regresses, during gestational week 6, the mesodermal ridges migrate toward the midline to form the final ventral wall. Bladder exstrophy results when the cloacal membrane fails to regress and does not allow the mesoderm to migrate. Cloacal exstrophy occurs when the cloacal membrane regresses before the urorectal septum develops and both the bladder and bowel become exposed.

Renal Function and Amniotic Fluid

The prognosis of renal abnormalities is worse when amniotic fluid volume is inadequate This poorer prognosis occurs as amniotic fluid is vital for lung development. Before 16 weeks of gestation, the amnion actively transports solutes and water diffuses passively across its membrane. Initially, during the first and second trimesters, the electrolytes and osmolarity of fetal urine is similar to that of fetal and maternal blood. Later in gestation, as the fetal kidney begins to absorb sodium and chloride as tubular function matures, the urine and amniotic fluid become more hypotonic.6 The result is a low electrolyte, high creatinine urinary composition, very similar to that seen postnatally. Kidneys which have sustained prenatal damage produce isotonic urine as they have lost the ability to reabsorb electrolytes and protein.

Before 16 weeks’ gestation, the amount of amniotic fluid may be relatively normal, even with poor renal function, as most of the amniotic fluid is produced by non-renal sources. After 16 weeks’ gestation, the kidneys become primarily responsible for most of the amniotic fluid volume. By the third trimester, the hourly fetal urine production is as high as 30–40 mL/hour and constitutes around 90% of the amniotic fluid.7

Amniotic fluid has long been recognized as playing an important role in fetal lung development. Reduced amniotic fluid volume results in varying degrees of pulmonary hypoplasia. It is unclear whether amniotic fluid plays merely a mechanical role in fetal lung development or if it supplies renal-derived growth factors. What is clear is its importance in preventing pulmonary hypoplasia, which, when severe, is fatal. Potter’s syndrome (severe pulmonary hypoplasia associated with bilateral renal agenesis), is fatal and occurs when there is a severe renal abnormality or urinary obstruction, resulting in severe oligohydramnios early in gestation.8

Epidemiology

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract9 occur in 1/500 live births and the incidence of neonatal death from CAKUT is about 1/2000 live births.9,10 Hydronephrosis is the most common prenatal urinary abnormality identified, occurring in 1–5% of all pregnancies, with the risk of any postnatal pathology increasing per degree of hydronephrosis (11.9% for mild, 45.1% for moderate and 88.3% for severe hydronephrosis).11 Most obstructive urologic anomalies occur in males, with a male to female ratio of 4:1, with a predilection for the left kidney to be involved,12,13

Pathogenesis

Fetal uropathy may be caused by genetic issues, such as autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease, or problems associated with nephrogenesis and urinary tract obstruction. Defective nephrogenesis may result in renal agenesis as well as renal dysplasia. Renal dysplasia may result from a defective interaction between the ureteric bud and metanephric mesenchyme, intrinsic defects of differentiation, as well as obstruction. Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract include renal agenesis, multicystic kidney, renal dysplasia, renal duplication anomalies, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, megaureters, posterior urethral valves and vesicoureteral reflux. CAKUT commonly results in renal dysplasia and a possible genetic cause has been considered, as renal abnormalities have been identified in close relatives of 10% of CAKUT patients.9,10 Numerous genetic mutations, such as abnormalities with HNF1β, PAX2 and RET signaling, have been considered, but no clear pattern of inheritance has been identified,14,15

Evaluation and Diagnosis

As previously mentioned, prenatal ultrasound detects 84.4–97% of all fetal urinary tract malformations and these anomalies may be detected as early as 12–14 weeks of gestation.1,2 Many of these abnormalities can be diagnosed via ultrasound, with fetal MRI providing greater clarification. In addition, many of these genitourinary conditions overlap in presentation on initial imaging.

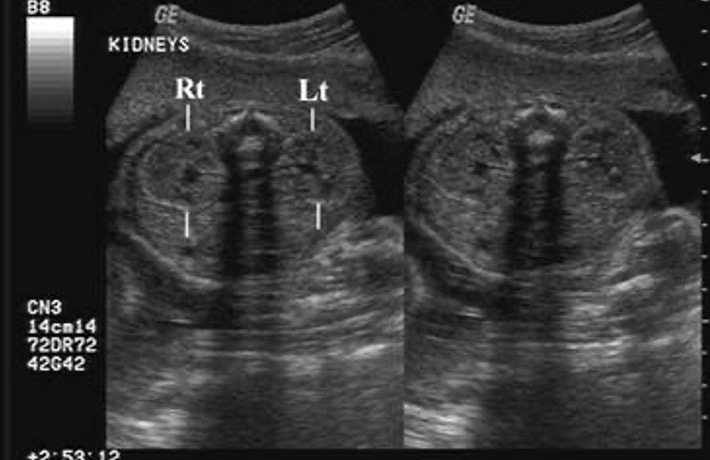

Prenatal Ultrasonography

Prenatal ultrasonography is now regularly used as screening and surveillance for fetal growth and development in the second trimester. Detection of urologic anomalies before birth is relatively sensitive, with upwards of 88% of urinary tract abnormalities diagnosed prenatally.16 The kidneys are generally not seen on ultrasound until week 15 of gestation (Figure 3) Anterior-posterior renal pelvic diameter (APRPD) less than 4 mm between weeks 16–27 of gestation and less than 7 mm at week 28 or greater are considered within the normal physiologic range.17 If the ureters are not dilated, they should not be visible on prenatal ultrasound. The bladder can generally be seen at 10 weeks’ gestation but should be visualized by 12 weeks. A normal bladder wall is no thicker than 3 mm.2

Figure 3 Prenatal ultrasound depicting normal left and right kidney.

Fetal Mri

Fetal MRI is commonly utilized to provide more anatomic detail of congenital abnormalities first detected on ultrasound. In one study, the overall diagnostic sensitivity was 96% for fetal MRI compared to 58% for ultrasound.18 Fetal MRI also provides additional diagnostic information, particularly in evaluation of ureteral anatomy. Benefits of fetal MRI include increased tissue contrast and examination of morphology, and ability to detect additional abnormalities and assess fetal renal function.19 As fetal imaging becomes more advanced, techniques such as 3D virtual cystoscopy are being used to further elucidate urogenital abnormalities.20

On MRI, the bladder will appear as a round/ovoid structure with a uniform high signal and its wall should be smooth and uniform in thickness. The kidneys will be located paraspinally within the upper abdomen and are seen as ovoid structures with an intermediate signal on a T2-weighted sequence. They should be examined for size, dysplastic changes, pelviectasis, and ureterectasis.

Prenatal Anomalies

Upper Urinary Tract Dilation

Hydronephrosis is detected in 1–5% of prenatal ultrasounds.21 Upper urinary tract dilation needs to be taken into consideration with other findings, such as the appearance of the renal parenchyma, amniotic fluid volume, ureteral dilation, or the appearance of the fetal bladder and urethral dilation.22,23 The three most common anomalies related to prenatal upper tract dilation are ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) abnormalities, ureterovesical junction (UVJ) abnormalities, and vesicoureteral reflux (VUR).

Hydronephrosis Grading Systems

To help better delineate the degree of hydronephrosis, different grading systems have been devised. The main grading systems used for hydronephrosis are the Society for Fetal Urology (SFU)24 and urinary tract dilation (UTD) systems.25 The APRPD has also been used as an adjunct to these grading systems.26

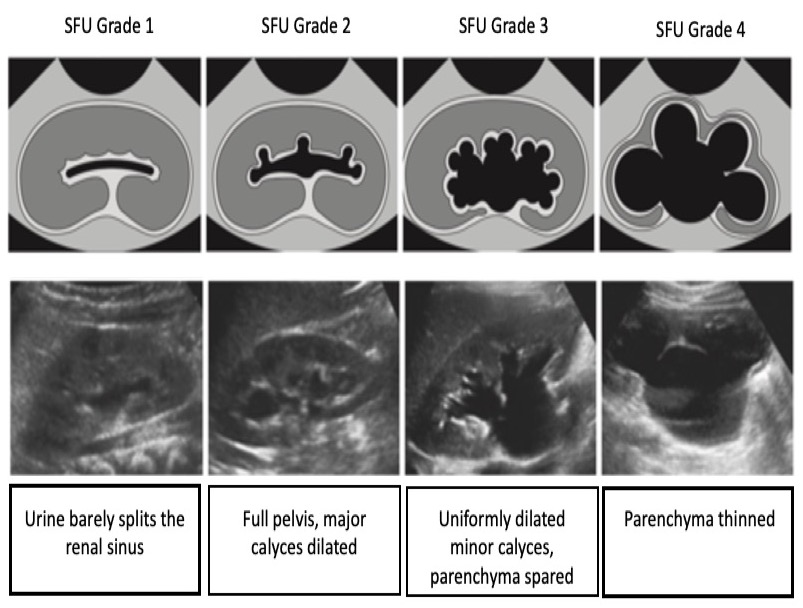

Sfu Grading System

In the SFU system, hydronephrosis grading is based upon the degree of dilation of the renal pelvis and calyces. (Figure 4) depicts the SFU grading system. Importantly, SFU grading was not originally conceived for antenatal evaluation and it has not been widely adopted outside of pediatric urology

Figure 4 SFU hydronephrosis grading system.

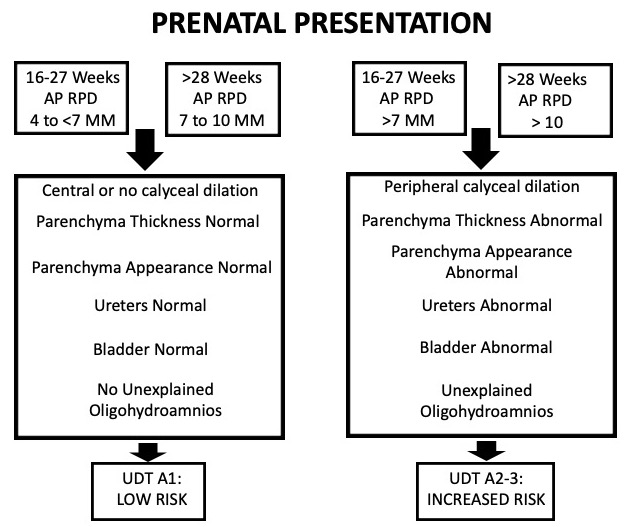

Utd Hydronephrosis Grading System

This system is based on six categories that are routinely identified on ultrasound: anterior-posterior renal pelvic diameter (APRPD), dilation of the renal calices, thickness of the renal parenchyma, appearance of the renal parenchyma, bladder abnormalities, and ureteral abnormalities. This grading system is also stratified by gestational age. For prenatal hydronephrosis, the hydronephrosis may be classified as UTD A1: low risk if there is central or calyceal dilation, but all of the aforementioned parameters are normal. UTD A2–3 is used if there is an increased risk for postnatal uropathies. Here, the intermediate (A2) and high risk (A3) groups are grouped into one category (Figure 5)

Figure 5 Table depicting the UTD classification system when hydronephrosis presents prenatally.

Hydronephrosis/Ureteropelvic Junction

In most cases of isolated antenatal hydronephrosis, this finding is suggestive of a transient and non-pathologic process.11 UPJ obstruction may be suggested by degree of hydronephrosis. The risk of any postnatal pathology increases significantly based upon the severity of prenatal hydronephrosis. The risk of postnatal pathology for mild, moderate and severe prenatal hydronephrosis has been reported to be 11.9%, 45.1% and 88.3%, respectively.11 Ureterovesical junction obstruction may also be suggested with the finding of hydronephrosis and ureteral dilation.

The need for further prenatal imaging may be based upon anteroposterior pelvic diameter. In one study, no infants with a second trimester APRPD <7 mm required postnatal intervention and none developed renal insufficiency.27 Another study suggested that a 15 mm renal pelvis dilation was a significant threshold to suspect obstruction in 80% of fetuses, with a sensitivity and specificity of 73% and 82%, respectively.28 In addition, a cutoff of 18 mm for fetal pelvic dilation had been found to have a diagnostic odds ratio of 97.7 for identifying infants who required pyeloplasty.29

Vesicoureteral Reflux

In the 2010 Pediatric Vesicoureteral Reflux Guidelines panel summary report, the authors noted that of the 6,579 infants with prenatal hydronephrosis, VUR was present in 4756 (72%).30 Despite these findings, prenatal imaging has a poor sensitivity in detecting VUR. Even if renal pelvic diameter (RPD) increases on prenatal ultrasound, increasing RPD is not predictive of VUR.31,32 Another study identified, that change in shape/size of the renal pelvis and ureter on prenatal imaging occurred in only 17.2% of fetuses who were diagnosed with postnatal VUR, making this is poor predictor of urinary reflux.32

Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction

Lower urinary tract obstruction constitutes a group of urogenital abnormalities that result in urethral obstruction. Antenatal presentation of these conditions is similar and generally takes on the form of a distended bladder and hydroureteronephrosis.

Identifying LUTO is important because of its potential long-term impact on renal function as well as prenatal lung development, especially if associated oligohydramnios is present. Ultrasound and patient characteristics which may be predictive of LUTO are severe megacystis (defined as bladder volume >35 mm3), bilateral ureteral dilation, oligo/anhydroamnios and male fetal sex.33 MRI can assist in evaluating renal parenchyma, kidney size, amount of amniotic fluid, and degree of ureteral and bladder distention.34 In addition, measuring parenchymal area may correlate with postnatal renal function, with 8 cm2 and greater during the third trimester, as the best predictor of end-stage renal disease development.35

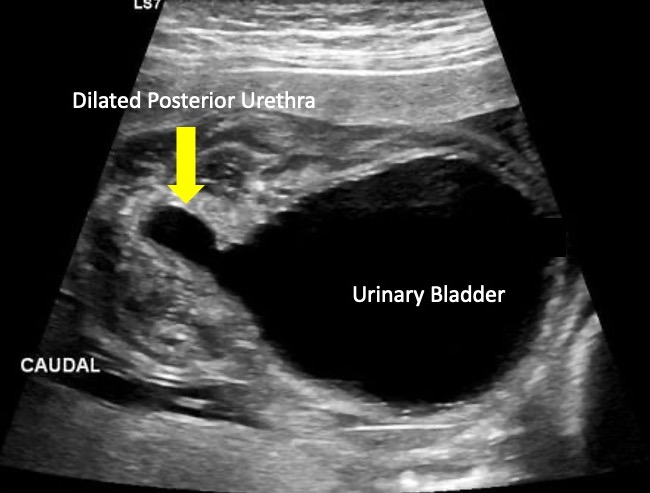

Posterior Urethral Valves

Posterior urethral valves can manifest as hydronephrosis, hydroureteronephrosis, or megacystis on prenatal ultrasound. However, the sonographic hallmark of PUV is a keyhole-shaped bladder with mild dilation of the proximal urethra (Figure 6) The prenatal ultrasonographic findings most predictive of the diagnosis of PUV include a dilated posterior urethra (the most discriminatory ultrasound finding), a thickened bladder wall, and anhydroamnios.32

Figure 6 Ultrasonographic image depicting the “keyhole” sign commonly seen in posterior urethral valves.

Prune Belly Syndrome

As the severity of PBS is variable, its antenatal diagnosis is difficult. Generally, the kidneys appear hyperechoic and dysplastic, with dilation of the ureters and a thickened bladder wall. Anhydroamnios and compressed abdominal and thoracic contents may also be seen.36,37 The earlier the suspicion for PBS occurs on prenatal imaging, the worse the prognosis. MRI can further delineate the extent of genitourinary abnormalities, including renal hypoplasia, dysplasia, ureteral dilation, megacystis, dilated prostatic urethra, and prostatic hypoplasia.34

Urethral Atresia and Anterior Urethral Abnormalities

Urethral atresia is just one condition under the umbrella of anterior urethral anomalies, which also includes anterior urethral valves and urethral diverticulum. Urethral atresia and anterior urethral anomalies are rare, but may be suspected when finding hydroureteronephrosis, a dilated and thickened bladder, oligohydramnios, as well as a dilated urethra on prenatal imaging. Additional congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract increase the likelihood of developing chronic kidney disease.38

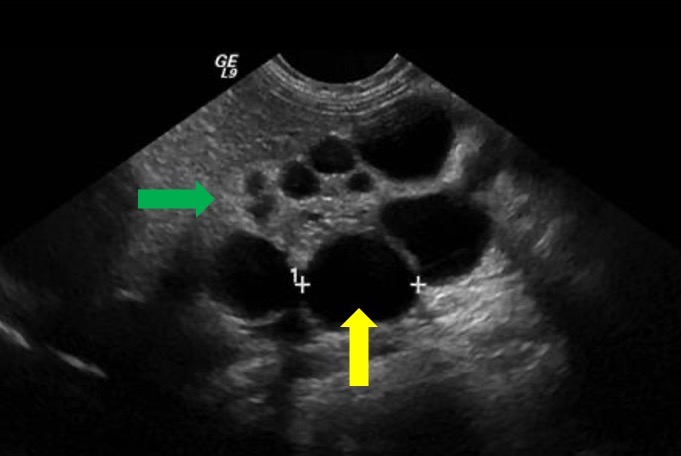

Multicystic Dysplastic Kidney

Prenatal renal cystic disease is difficult to identify and distinguish using only ultrasound. Often, it may be difficult to distinguish MCDK from a severe UPJ obstruction on prenatal ultrasound. Fetal MRI has been used to complement initial ultrasound findings concerning for MCDK. Classically, the kidney will be completely replaced by cysts of different sizes that do not communicate (Figure 7) A normal renal pelvis is typically not seen, due to lack of tubular branching development and may be a characteristic finding for MCDK.39 Beyond MCDK, renal cysts found on prenatal imaging can also be indicative of renal cystic dysplasia/disease.

Figure 7 Ultrasound image depicting MCDK. Yellow arow depicts renal cyst. Green arrow depicts echogenic thinned renal parenchyma suggestive of renal dysplasia.

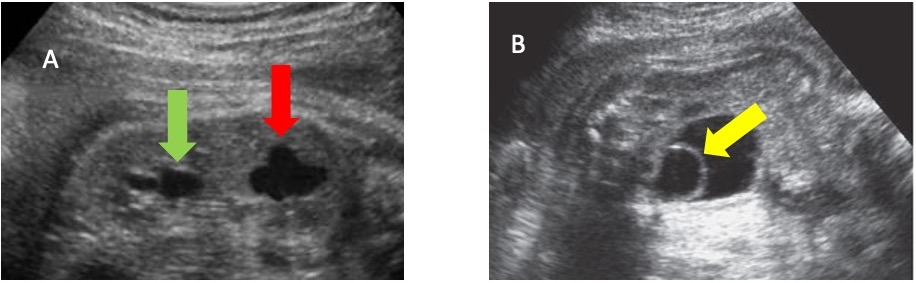

Duplication Anomalies

The diagnostic accuracy of prenatal ultrasound in identifying isolated duplex collecting systems is as high as 90%.40 When there is ureteral duplication, a ureterocele may be associated with the upper pole moiety. Even though most duplication anomalies may be diagnosed using ultrasonography (Figure 8), MRI may be helpful in distinct cases.41 One study reported that in patients with a prenatal diagnosis of isolated duplex collecting system, ureterocele and megaureter were associated with 70.7% and 36.6% of cases, respectively.40

Figure 8 A. Ultrasound image depicting duplicated kidney with hydronephrosis within lower pole (green arrow) and upper pole (red arrow). B. Ultrasound image depicting urinary bladder with ureterocele (yellow arrow) within it.

Bladder Exstrophy, Cloaca, Urogenital Sinus

Bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy may also be seen on prenatal imaging. The correct differentiation between bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy may be accomplished by identifying the location of umbilical cord insertion relative to the abdominal wall defect (superior vs. mid vs. inferior), which can be accomplished either with fetal ultrasound or MRI.42 If the defect in the abdominal wall is seen inferior to the cord without a full bladder, the diagnosis is likely bladder exstrophy. Meanwhile, if the defect is at the level of the cord or superior to it, the diagnosis is more likely an omphalocele.

Bladder exstrophy on MRI will be seen as an infraumbilical abdominal wall mass, with low insertion of the umbilical cord. Because the kidneys and ureters should be normal, there will be a normal amount of amniotic fluid. Diastasis of the pubic symphysis may also be noted.

Prenatal ultrasound findings suggestive of classic cloaca malformations include one to two adjacent cysts seen in the female fetal pelvis, transient ascites, and high position of the rectum with superior dilation and blunted or beaked distal tapering as well as hydronephrosis and megacystis. The most specific features supporting the diagnosis of cloacal malformation is a fluid-filled dilated colon with enteroliths and presence of meconium in the urinary tract. Additional findings on fetal MRI suggestive of cloacal exstrophy include an absent bladder with normal amniotic fluid volume, protuberant anterior pelvic contour, lack of meconium in the bowel, and omphalocele.43 Fetal MRI can also contribute to the identification of the number and location of perineal orifices.

In persistent urogenital sinus, fetal ultrasound may show hydrometrocolpos as an oblong, anechoic, and septate lesion located behind the fetal bladder.44 On MRI, a urogenital sinus will present with a normal rectum and colon caliber. The meconium signal will also be normal. The anal perineal orifice will be in its physiologic location. There will be a common urogenital channel with an orifice on the perineum where the urethra should be located.45

Treatment Options

From a urologic perspective, most prenatal interventions are performed for lower urinary tract obstruction. Interventions are performed to alleviate the obstruction, in an attempt to maximize renal function and normalize amniotic fluid levels to prevent damage associated with oligohydramnios.

There are two current widely accepted interventions for prenatal LUTO: vesicoamniotic shunt placement and fetal cystoscopy. Fetal intervention is primarily focused on the decompression of the upper urogenital tract to prevent ongoing renal parenchymal damage and restoration of amniotic fluid volume for pulmonary development. Prior to consideration of any prenatal intervention, evaluation is necessary for risk assessment for intervention and should begin with two consecutive vesicocenteses.46,47,48,49 In conjunction with the sonographic appearance of the kidneys, utilization of the Glick criteria can be used as a prognostic factor for further fetal intervention in addition to a therapeutic intervention (Table 1).50 It is worth noting that this prognostication is not adjusted for fetal age and is not necessarily reflective of postnatal function.48

Table 1 Prognostic Criteria for Fetus with Obstructive Uropathy

| Predicted function | Amniotic fluid status at time of initial presentation | Sonographic appearance of kidneys | Fetal urine – sodium (mEq/mL) | Fetal urine – chloride (mEq/mL) | Fetal urine – osmolarity (mOsm) | Fetal urine output (mL/hour) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Moderate to severely decreased | Echogenic to cystic | > 100 | > 90 | > 210 | < 2 |

| Good | Normal to moderately decreased | Normal to echogenic | < 100 | < 90 | < 210 | > 2 |

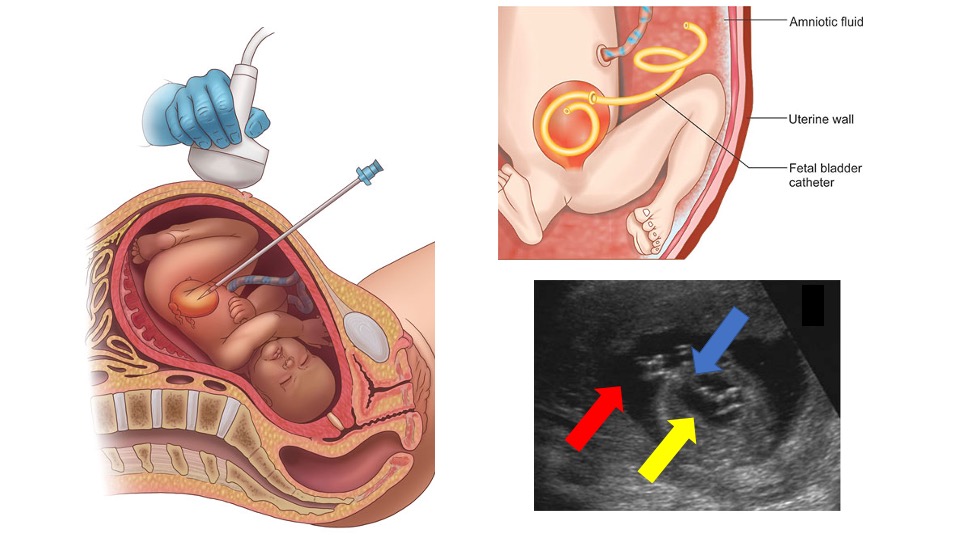

Vesicoamniotic Shunting

Vesicoamniotic shunting is performed with local anesthesia under real-time, two-dimensional ultrasound guidance.51,52 Under sterile technique, a vesicoamniotic catheter is percutaneously inserted with optimal placement where the distal end of the shunt lies in the fetal bladder and the proximal end in the amniotic cavity (Figure 9)52 Early models detail the use of double-ended pigtail catheters, while more recent studies have explored double-basket catheters as an alternative modality. Variable outcomes have been reported, with survival rates ranging from 41% to 80%, depending on patient selection,53,54 The most recent randomized PLUTO trial encountered significant issues with patient recruitment, leading to premature termination of the study while trying to provide further clarity on the utility of vesicoamniotic shunting.52 This study, along with other small retrospective analyses and anecdotal evidence, has shown an improvement in perinatal survival,53,54,55 although longer term outcomes remain unclear. All studies highlight the need for further prospective, randomized control studies for this intervention.

Figure 9 Depiction of ultrasonographic guidance placing a vesicoamniotic shunt, final shunt placement and an ultrasound showing the shunt (blue arrow) within the urinary bladder (yellow arrow) and amniotic space (red arrow).

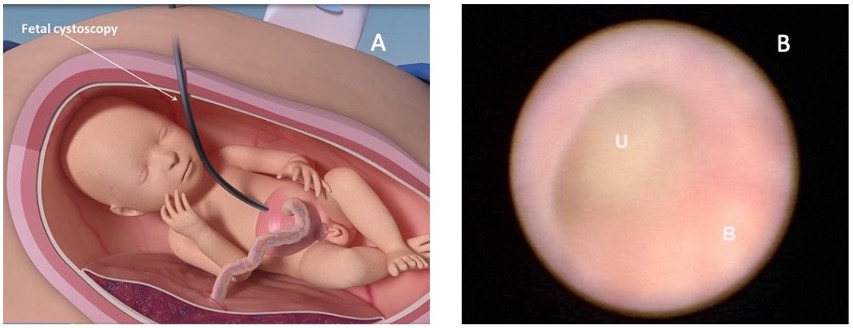

Cystoscopy

In utero fetal cystoscopy was first reported in 1995.56 Although technically more challenging than vesicoamniotic shunting, this intervention allows for direct visualization, ascertainment of a specific diagnosis, and possible treatment at time of diagnosis. A trocar larger than that used for vesicoamniotic shunting is utilized and a 1.0–1.3 mm fetoscope in a curved sheath with at least a 70° field of view is used.57 One of the most common anomalies noted on fetal cystoscopy is posterior urethral valves (PUV). If a membranous structure is noted on cystoscopy and PUV is diagnosed, laser fulguration, hydroablation, or guide-wire perforation may be used as methods of immediate intervention (Figure 10)58 Urethral stenosis is an intraoperative cystoscopic diagnosis that may be successfully treated with a urethral stent placement over a wire.57 If urethral atresia is instead diagnosed, perforation of the urethra is not attempted, and VAS is completed.59

Figure 10 Image A depicts how fetal cystoscopy is performed. Image B shows a fetal cystoscopic image within the bladder (B) and the point of obstruction within the urethra (U). Imaged obtained from: Prenatal regenerative fetoscopic interventions for congenital anomalies. SBRE 2020.

A video depicting fetal intervention for LUTO is available (Video 3). In addition, a podcast reviewing prenatal interventions for LUTO is available.

Video 3. Depiction of fetal intervention for LUTO.

Complications

Prenatal interventions for LUTO are not without risk and possible complication. One risk associated with both VAS and in-utero fetal cystoscopy is premature rupture of membranes, which may lead to preterm labor.60 Vesicoamniotic shunting complications include risk of shunt blockage and dislodgement, both of which can result in fetal demise.55 In addition, reports of misplacement of the shunt into surrounding intra-abdominal organs have been reported.61 Fetal cystoscopy with laser ablation has been associated with a 10% fistula rate which varied by gestational age, curved versus semi-curved sheaths, laser type and settings, as well as operator experience in a statistically significant manner.62

Conclusions

Urologic abnormalities are commonly detected on the routine prenatal second trimester comprehensive fetal anatomic survey. The most common abnormality identified is prenatal hydronephrosis, which typically is transient. However, other genitourinary abnormalities detected prenatally may have worse outcome. In particular, lower urinary tract obstruction can lead to marked morbidity and mortality in the fetus. At times, prenatal treatment may be warranted in attempts to preserve renal function and prevent pulmonary hypoplasia.

Key Points

- Antenatal hydronephrosis is seen in 1–5% of all pregnancies and represents the most frequent prenatal diagnosis.

- Prenatal Anterior-Posterior Renal Pelvic Diameter ( APRPD) less then 4 mm between weeks 16–27 of gestation and less then 7 mm at week 28 or greater of gestation are considered within the physiologic range.

- There are many urogenital conditions and abnormalities that are detected via prenatal imaging. Many of these can be diagnosed via ultrasound, with fetal MRI providing greater clarification.

- Lower urinary tract obstruction without intervention can lead to marked morbidity and mortality in the fetus. Although several treatment modalities exist, large scale studies are required to determine efficacy in preserving renal function and preventing pulmonary hypoplasia.

Suggested Readings

- Lee RS, Cendron M, Kinnamon DD, Nguyen HT. Antenatal Hydronephrosis as a Predictor of Postnatal Outcome: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2006; 118 (2): 586–593. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0120.

- Mallik M, Watson AR. Antenatally detected urinary tract abnormalities: more detection but less action. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23 (6): 897–904. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-008-0746-9.

- Fernbach SK, Maizels M, Conway JJ. Ultrasound grading of hydronephrosis: Introduction to the system used by the society for fetal urology. Pediatr Radiol 1993; 23 (6): 478–480. DOI: 10.1007/bf02012459.

- Nguyen HT, Benson CB, Bromley B, Campbell JB, Chow J, Coleman B, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Multidisciplinary consensus on the classification of prenatal and postnatal urinary tract dilation (UTD classification system). Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2014; 0 (6): 82–98. DOI: 10.3410/f.725257762.793506733.

- Haeri S. Fetal Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction (LUTO): a practical review for providers. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 0AD; 1 (1). DOI: 10.1186/s40748-015-0026-1.

References

- Bronshtein M, Yoffe N, Brandes JM, Blumenfeld Z. First and early second-trimester diagnosis of fetal urinary tract anomalies using transvaginal sonography. Prenat Diagn 1990; 10 (10): 653–666. DOI: 10.1002/pd.1970101005.

- Corteville JE, Gray DL, Crane JP. Congenital hydronephrosis: Correlation of fetal ultrasonographic findings with infant outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991; 165 (2): 384–388. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(91)90099-d.

- Mallik M, Watson AR. Antenatally detected urinary tract abnormalities: more detection but less action. Pediatr Nephrol 2008; 23 (6): 897–904. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-008-0746-9.

- Alcaraz A, Vinaixa F, Tejedo-Mateu A, Forés MM, Gotzens V, Mestres CA, et al.. Obstruction and Recanalization of the Ureter during Embryonic Development. J Urol 1991; 145 (2): 410–416. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38354-4.

- Saphier CJ, Gaddipati S, Applewhite LE, Berkowitz RL. Prenatal Diagnosis And Management Of Abnormalities In The Urologic System. Clin Perinatol 2000; 27 (4): 921–945. DOI: 10.1016/s0095-5108(05)70058-0.

- Glibert WM, Moore TR, Brace RA. Amniotic fluid volume dynamics. Fetal Matern Med Rev 1991; 3 (2): 89–104. DOI: 10.1017/s0965539500000486.

- Rabinowitz R, Peters MT, Vyas S, Campbell S, Nicolaides KH. Measurement of fetal urine production in normal pregnancy by real-time ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989; 161 (5): 1264–1266. DOI: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90679-0.

- Pitkin R. Potter EL. Bilateral absence of ureters and kidneys: a report of 50 cases. Obstet Gynecol 1965;25:3–12. Obstet Gynecol 0AD; 101 (6): 1159. DOI: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02394-3.

- Renkema KY, Winyard PJ, Skovorodkin IN, Levtchenko E, Hindryckx A, Jeanpierre C, et al.. Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT). Lijec Vjesn 2011; 144 (Supp 1): 843–851. DOI: 10.26800/lv-144-supl1-26.

- Hogan J, Dourthe M-E, Blondiaux E, Jouannic J-M, Garel C, Ulinski T. Renal outcome in children with antenatal diagnosis of severe CAKUT. Pediatr Nephrol 2012; 27 (3): 497–502. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-011-2068-6.

- Lee RS, Cendron M, Kinnamon DD, Nguyen HT. Antenatal Hydronephrosis as a Predictor of Postnatal Outcome: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2006; 118 (2): 586–593. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-0120.

- Shih VE, Laframboise R, Mandell R, Pichette J. Neonatal form of the hyperornithinaemia, hyperammonaemia, and homocitrullinuria (HHH) syndrome and prenatal diagnosis. Prenat Diagn 0AD; 12 (9): 717–723. DOI: 10.1002/pd.1970120905.

- Harrison MR, Golbus MS, Filly RA, Nakayama DK, Callen PW, Lorimier AAde, et al.. Management of the fetus with congenital hydronephrosis. J Pediatr Surg 1982; 17 (6): 728–742. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(82)80437-5.

- Paces-Fessy M, Fabre M, Lesaulnier C, Cereghini S. Hnf1b and Pax2 cooperate to control different pathways in kidney and ureter morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2012; 21 (14): 3143–3155. DOI: 10.1093/hmg/dds141.

- Allison SJ. Ret signaling reveals insights into the pathogenesis of CAKUT. Nat Rev Nephrol 2012; 8 (8): 432–432. DOI: 10.1038/nrneph.2012.119.

- Clayton DB, Brock JW. Prenatal Ultrasound and Urological Anomalies. Pediatr Clin North Am 0AD; 59 (4): 739–756. DOI: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.05.003.

- Grignon A, Filion R, Filiatrault D, Robitaille P, Homsy Y, Boutin H, et al.. Urinary tract dilatation in utero: classification and clinical applications. Radiology 1986; 160 (3): 645–647. DOI: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.3526402.

- Kajbafzadeh A-M, Payabvash S, Sadeghi Z, Elmi A, Jamal A, Hantoshzadeh Z, et al.. Comparison of magnetic resonance urography with ultrasound studies in detection of fetal urogenital anomalies. J Pediatr Urol 2008; 4 (1): 32–39. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.07.005.

- Chalouhi GE, Millischer A-É, Mahallati H, Siauve N, Melbourne A, Grevent D, et al.. The use of fetal MRI for renal and urogenital tract anomalies. Prenat Diagn 2020; 40 (1): 100–109. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5610.

- Werner H, Lopes J, Ribeiro G, Jésus NR, Santos GR, Alexandria HAF, et al.. Three-dimensional virtual cystoscopy: Noninvasive approach for the assessment of urinary tract in fetuses with lower urinary tract obstruction. Prenat Diagn 2020; 37 (13): 1350–1352. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5188.

- Swenson DW, Darge K, Ziniel SI, Chow JS. Characterizing upper urinary tract dilation on ultrasound: a survey of North American pediatric radiologists’ practices. Pediatr Radiol 2015; 45 (5): 686–694. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-014-3221-8.

- Mure P-Y, Mouriquand P. Upper urinary tract dilatation: Prenatal diagnosis, management and outcome. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2008; 13 (3): 152–163. DOI: 10.1016/j.siny.2007.09.010.

- Mouriquand PDE, Whitten M, Pracros J-P. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of prenatal upper tract dilatation. Prenat Diagn 2001; 21 (11): 942–951. DOI: 10.1002/pd.207.

- Fernbach SK, Maizels M, Conway JJ. Ultrasound grading of hydronephrosis: Introduction to the system used by the society for fetal urology. Pediatr Radiol 1993; 23 (6): 478–480. DOI: 10.1007/bf02012459.

- Nguyen HT, Benson CB, Bromley B, Campbell JB, Chow J, Coleman B, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Multidisciplinary consensus on the classification of prenatal and postnatal urinary tract dilation (UTD classification system). Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2014; 0 (6): 82–98. DOI: 10.3410/f.725257762.793506733.

- Onen A. Grading of Hydronephrosis: An Ongoing Challenge. Front Pediatr 0AD; 8 (458). DOI: 10.3389/fped.2020.00458.

- Roo R de, Voskamp BJ, Kleinrouweler CE, Mol BW, Pajkrt E, Bouts AHM. Determination of threshold value for follow-up of isolated antenatal hydronephrosis detected in the second trimester. J Pediatr Urol 2017; 13 (6): 594–601. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.06.001.

- Coplen DE, Austin PF, Yan Y, Blanco VM, Dicke JM. The Magnitude of Fetal Renal Pelvic Dilatation can Identify Obstructive Postnatal Hydronephrosis, and Direct Postnatal Evaluation and Management. Yearbook of Urology 2006; 2007 (2): 237–238. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(08)70187-8.

- Dias CS, Silva JM, Pereira AK, Marino VS, Silva LA, Coelho AM, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Diagnostic accuracy of renal pelvic dilatation for detecting surgically managed ureteropelvic junction obstruction. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2013; 90 (2): 61–66. DOI: 10.3410/f.718084698.793482695.

- Skoog SJ, Peters CA, Arant BS Jr., Copp HL, Elder JS, Hudson RG, et al.. Pediatric Vesicoureteral Reflux Guidelines Panel Summary Report: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Screening Siblings of Children With Vesicoureteral Reflux and Neonates/Infants With Prenatal Hydronephrosis. Yearbook of Urology 2010; 2011 (3): 205–207. DOI: 10.1016/j.yuro.2010.12.022.

- Dias CS, Bouzada MCF, Pereira AK, Barros PS, Chaves ACL, Amaro AP, et al.. Predictive Factors for Vesicoureteral Reflux and Prenatally Diagnosed Renal Pelvic Dilatation. J Urol 2009; 182 (5): 2440–2445. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.07.058.

- Chitrit Y, Bourdon M, Korb D, Grapin-Dagorno C, Joinau-Zoulovits F, Vuillard E, et al.. Posterior urethral valves and vesicoureteral reflux: can prenatal ultrasonography distinguish between these two conditions in male fetuses? Prenat Diagn 2016; 36 (9): 831–837. DOI: 10.1002/pd.4868.

- Fontanella F, Duin LK, Scheltema PN Adama van, Cohen-Overbeek TE, Pajkrt E, Bekker M, et al.. Prenatal diagnosis of LUTO: improving diagnostic accuracy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018; 52 (6): 739–743. DOI: 10.1002/uog.18990.

- Chauvin NA, Epelman M, Victoria T, Johnson AM. Complex Genitourinary Abnormalities on Fetal MRI: Imaging Findings and Approach to Diagnosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199 (2): W222–w231. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.11.7761.

- Moscardi PRM, Katsoufis CP, Jahromi M, Blachman-Braun R, DeFreitas MJ, Kozakowski K, et al.. Re: Prenatal Renal Parenchymal Area as a Predictor of Early End-Stage Renal Disease in Children with Vesicoamniotic Shunting for Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction. J Urol 2018; 204 (5): 1083–1083. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001254.

- Alkhamis WH, Abdulghani SH, Altaki A. Challenging diagnosis of prune belly syndrome antenatally: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2019; 13 (1): 98. DOI: 10.1186/s13256-019-2120-x.

- Ome M, Wangnapi R, Hamura N, Umbers AJ, Siba P, Laman M, et al.. A case of ultrasound-guided prenatal diagnosis of prune belly syndrome in Papua New Guinea – implications for management. BMC Pediatr 0AD; 13 (1). DOI: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-70.

- Perlman S, Borovitz Y, Ben-Meir D, Hazan Y, Nagar R, Bardin R, et al.. Prenatal diagnosis and postnatal outcome of anterior urethral anomalies. Prenat Diagn 2020; 40 (2): 191–196. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5582.

- Meyers ML, Treece AL, Brown BP, Vemulakonda VM. Imaging of fetal cystic kidney disease: multicystic dysplastic kidney versus renal cystic dysplasia. Pediatr Radiol 2020; 50 (13): 1921–1933. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-020-04755-5.

- Bascietto F, Khalil A, Rizzo G, Makatsariya A, Buca D, Silvi C, et al.. Prenatal imaging features and postnatal outcomes of isolated fetal duplex renal collecting system: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prenat Diagn 2020; 40 (4): 424–431. DOI: 10.1002/pd.5622.

- Sozubir S, Lorenzo AJ, Twickler DM, Baker LA, Ewalt DH. Prenatal diagnosis of a prolapsed ureterocele with magnetic resonance imaging. Urology 2003; 62 (1): 144. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00152-3.

- Weiss DA, Oliver ER, Borer JG, Kryger JV, Roth EB, Groth TW, et al.. Key anatomic findings on fetal ultrasound and MRI in the prenatal diagnosis of bladder and cloacal exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (5): 665–671. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.07.024.

- Clements MB, Chalmers DJ, Meyers ML, Vemulakonda VM. Prenatal Diagnosis of Cloacal Exstrophy: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Urology 2014; 83 (5): 1162–1164. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.10.050.

- Giuliani M, Gui B, Laino M, Zecchi V, Rodolfino E, Ninivaggi V, et al.. Persistent Urogenital Sinus: Diagnostic Imaging for Clinical Management. What Does the Radiologist Need to Know? Am J Perinatol 2016; 33 (05): 425–432. DOI: 10.1055/s-0035-1565996.

- Capito C, Belarbi N, Paye Jaouen A, Leger J, Carel J-C, Oury J-F, et al.. Prenatal pelvic MRI: Additional clues for assessment of urogenital obstructive anomalies. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (1): 162–166. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.07.020.

- Craparo FJ, Rustico M, Tassis B, Coviello D, Nicolini U. Fetal Serum \ensuremathβ2-Microglobulin Before and After Bladder Shunting: A 2-Step Approach to Evaluate Fetuses With Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction. J Urol 2007; 178 (6): 2576–2579. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.052.

- FISK NM, RONDEROS-DUMIT D, TANNIRANDORN Y, NICOLINI U, TALBERT D, RODECK CH. Normal amniotic pressure throughout gestation. Bjog 1992; 99 (1): 18–22. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1992.tb14385.x.

- Nicolini U, Tannirandorn Y, Vaughan J, Fisk NM, Nicolaidis P, Rodeck CH. Further predictors of renal dysplasia in fetal obstructive uropathy: Bladder pressure and biochemistry of ‘fresh’ urine. Prenat Diagn 1991; 11 (3): 159–166. DOI: 10.1002/pd.1970110305.

- Johnson MP, Freedman AL. Fetal uropathy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 1999. 0AD; 1 (2): 85–94. DOI: 10.1097/00001703-199904000-00011.

- Glick PL, Harrison MR, Golbus MS, Adzick NS, Filly RA, Callen PW, et al.. Management of the Fetus With Congenital Hydronephrosis II: Prognostic Criteria and Selection for Treatment. J Urol 1985; 135 (2): 444–445. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)45673-4.

- Kilby MD, Morris RK. Fetal therapy for the treatment of congenital bladder neck obstruction. Nat Rev Urol 2014; 11 (7): 412–419. DOI: 10.1038/nrurol.2014.132.

- Morris RK, Malin GL, Quinlan-Jones E, Middleton LJ, Diwakar L, Hemming K, et al.. The Percutaneous shunting in Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction (PLUTO) study and randomised controlled trial: evaluation of the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunting for lower urinary tract obstruction. Health Technol Assess 2013; 17 (59): –232. DOI: 10.3310/hta17590.

- Manning FA, Harrison MR, Rodeck C, International Fetal Medicine of the, Surgery Society M. Catheter Shunts for Fetal Hydronephrosis and Hydrocephalus. N Engl J Med 1986; 315 (5): 336–340. DOI: 10.1056/nejm198607313150532.

- Won H-S, Kim S-K, Shim J-Y, Ryang Lee P, Kim A. Vesicoamniotic shunting using a double-basket catheter appears effective in treating fetal bladder outlet obstruction. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2006; 85 (7): 879–884. DOI: 10.1080/00016340500449923.

- Morris RK, Malin GL, Quinlan-Jones E, Middleton LJ, Hemming K, Burke D, et al.. Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Percutaneous vesicoamniotic shunting versus conservative management for fetal lower urinary tract obstruction (PLUTO): a randomised trial. F1000 - Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2013; 82 (9903): 496–506. DOI: 10.3410/f.718077679.793484579.

- Quintero RA, Johnson MP, Romero R, Cotton DB, Evans MI, Smith C, et al.. In-utero percutaneous cystoscopy in the management of fetal lower obstructive uropathy. Lancet 1995; 346 (8974): 537–540. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91381-5.

- Ruano R, Yoshizaki CT, Giron AM, Srougi M, Zugaib M. Cystoscopic placement of transurethral stent in a fetus with urethral stenosis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014; 44 (2): 238–240. DOI: 10.1002/uog.13293.

- Haeri S. Fetal Lower Urinary Tract Obstruction (LUTO): a practical review for providers. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol 0AD; 1 (1). DOI: 10.1186/s40748-015-0026-1.

- Ruano R, Sananes N, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Hernandez-Ruano S, Moog R, Becmeur F, et al.. Fetal intervention for severe lower urinary tract obstruction: a multicenter case-control study comparing fetal cystoscopy with vesicoamniotic shunting. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015; 45 (4): 452–458. DOI: 10.1002/uog.14652.

- Crombleholme TM, Harrison MR, Langer JC, Longaker MT, Anderson RL, Slotnick NS, et al.. Early experience with open fetal surgery for congenital hydronephrosis. J Pediatr Surg 1988; 23 (12): 1114–1121. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(88)80325-7.

- Mann S, Johnson MP, Wilson RD. Fetal thoracic and bladder shunts. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med 2010; 15 (1): 28–33. DOI: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.06.001.

- Sananes N, Favre R, Koh CJ, Zaloszyc A, Braun MC, Roth DR, et al.. Urological fistulas after fetal cystoscopic laser ablation of posterior urethral valves: surgical technical aspects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015; 45 (2): 183–189. DOI: 10.1002/uog.13405.

Ultima atualização: 2024-02-16 21:59