53: Traumatismo vesical y ureteral

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 20 minutos para leer.

Trauma vesical

Epidemiología

La incidencia de la ruptura vesical durante la infancia es baja, y esta condición representa alrededor del 5% de las lesiones del tracto urinario. Según la American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST), la mayoría (92%) de las lesiones vesicales son de grado III–IV.1

Las fracturas pélvicas se asocian con menor frecuencia al traumatismo vesical en los niños (3–4% de los casos) que en los adultos (70–80%). Otra diferencia en comparación con los adultos es que las laceraciones del cuello vesical están asociadas al traumatismo vesical en los niños con el doble de frecuencia. Este hecho es de gran importancia clínica en el diagnóstico y el tratamiento subsiguiente,2,3

Un factor importante en estas lesiones, especialmente en niños, es el grado de distensión vesical. Una vejiga completamente distendida puede romperse incluso con un golpe leve; sin embargo, una vejiga vacía rara vez se lesiona, excepto por lesiones por aplastamiento o penetrantes. En los niños que siguen un programa de cateterismo intermitente (CI) asociado con aumentos vesicales, la vejiga es más vulnerable y la perforación es más fácil.

Debido a la alta energía necesaria para lesionar la vejiga, el 60–90% de los pacientes que se presentan con lesión vesical tienen una fractura ósea pélvica, mientras que el 6–8% de los pacientes con una fractura pélvica presentarán una lesión vesical. Los pacientes pediátricos son más susceptibles a las lesiones vesicales debido a la anatomía infantil. Una fractura pélvica con hematuria se asocia con una lesión vesical en el 30% de los casos.4

Dentro de la cirugía abdominal, los procedimientos ginecológicos y obstétricos son los más frecuentes (52–61%), seguidos por las intervenciones urológicas (12–39%) y la cirugía general (9–26%).

Las lesiones iatrogénicas de la vejiga asociadas con la cirugía urológica ocurren durante procedimientos vaginales y la laparoscopia. En los niños sometidos a cirugía del canal inguinal, especialmente por criptorquidia intraabdominal, puede haber riesgo de lesión vesical. Durante la resección transuretral de tumores, el riesgo es generalmente bajo (1 %), y la mayoría de los casos (88 %) pueden tratarse mediante drenaje con un catéter vesical. La resección transuretral de la próstata también se asocia con tasas bajas de lesión.5

Clasificación

Las lesiones vesicales son principalmente de cuatro tipos: rotura vesical intraperitoneal (IBR), rotura vesical extraperitoneal (EBR), contusión vesical y avulsión del cuello vesical. La IBR se presenta en el 15–25% de los casos. La EBR es el tipo más común, encontrándose en el 60–90% de los pacientes, y se asocia con mayor frecuencia a fracturas pélvicas. La rotura vesical combinada, es decir, una combinación de IBR y EBR, se observa en el 5–12% de los casos. La EBR puede clasificarse además en EBR simple, en la que la fuga urinaria se limita a la región pélvica extraperitoneal, y lesiones complejas, en las que la orina extravasada infiltra la pared abdominal anterior, el escroto y el periné.6

Además, lesiones iatrogénicas pueden surgir durante cirugía abierta del abdomen inferior o cirugía pélvica (85% de los casos) o, con menor frecuencia, durante cirugía vaginal, laparoscopia o cirugía del canal inguinal. Además, es posible la aparición de lesiones espontáneas. En este tipo de lesión, el traumatismo vesical en un niño sano es extremadamente infrecuente y puede pasar desapercibido ante dolor abdominal, líquido intraabdominal libre o sepsis en neonatos. Se han descrito perforaciones en niños con divertículo vesical y en aquellos con agrandamiento vesical. La incidencia global de perforación vesical en niños sometidos a cistoplastia de aumento es del 5%, mientras que tras la cateterización vesical es del 1%; el 4% de los casos son espontáneos.7,8,9

Lesiones vesicales extraperitoneales

En estos casos, la extravasación de orina se limita al espacio perivesical. La mayoría se producen por traumatismos cerrados y en relación con fracturas del anillo pélvico. También pueden ocurrir en disyunciones pélvicas cuando la pared vesical se desgarra por tracción sobre los ligamentos pubovesicales.

Lesiones intraperitoneales de la vejiga

En estos casos, se rompe la superficie peritoneal. Lesiones de este tipo. El veinticinco por ciento ocurren en pacientes sin fracturas pélvicas. En los niños, son más frecuentes que las lesiones extraperitoneales y, en este grupo etario, representan el 77 % de las lesiones vesicales. Su incidencia puede haber aumentado debido al incremento progresivo en el uso del cinturón de seguridad.

La lesión se presenta con mayor frecuencia en la pared posterior de la vejiga y en la cúpula vesical, que es el lugar de menor resistencia. Otro factor que favorece este último sitio es la falta de protección ósea, por lo cual está más expuesto a posibles agentes traumáticos, especialmente durante el llenado,10,11

Diagnóstico

La obtención de la historia clínica es esencial, y deben recopilarse los mismos datos que en cualquier paciente politraumatizado. En caso de fracturas pélvicas, la anamnesis debe orientarse a una posible lesión vesical.

Manifestaciones clínicas

Las manifestaciones clínicas pueden ser muy diversas, dependiendo de la intensidad del traumatismo, de si es penetrante o no, de si la ruptura es intra- o extraperitoneal, y de las lesiones asociadas. Es importante sospechar dichas lesiones en pacientes con fracturas pélvicas y evitar que pasen desapercibidas, lo que conducirá a un retraso en el diagnóstico.

Los síntomas más frecuentes en los pacientes con lesiones vesicales significativas son la hematuria macroscópica y el dolor abdominal, y también puede ocurrir dificultad para la micción.

Hematuria macroscópica

Existe una estrecha correlación entre la rotura vesical traumática, la fractura pélvica y la hematuria macroscópica en el 85%. A veces se presenta uretrorragia, lo cual es importante considerar para las maniobras diagnósticas (cistografía), ya que la uretra puede estar lesionada.

La ausencia de hematuria no descarta la rotura vesical: el 2–10% de los pacientes con una rotura vesical presentan solo microhematuria o no presentan hematuria en absoluto (15.-17).

Dolor abdominal

Este es el síntoma más común después de la hematuria. Los pacientes con lesiones extraperitoneales tienden a presentar dolor abdominal difuso en el hipogastrio, mientras que aquellos con lesiones intraperitoneales suelen referir dolor a nivel de los hombros y en el centro de la espalda debido a la acumulación de orina en la cavidad abdominal y por debajo del diafragma. Estos últimos pueden pasar horas sin tener deseo de orinar debido a la extravasación de orina hacia la cavidad abdominal. Con esto en mente, se debe considerar la posibilidad de rotura vesical en pacientes con dolor abdominal sin una causa evidente, y especialmente en aquellos que se han sometido a cistoplastia de aumento y en quienes presentan extrofia vesical, divertículos vesicales o procesos inflamatorios de la vejiga. El retraso en el diagnóstico puede provocar complicaciones graves.

Retención urinaria

Debe descartarse la ausencia de micción sin catéter vesical y, si fuera necesario, otras causas como la anuria prerrenal o la lesión del tracto urinario superior.

Hematomas en la región suprapúbica, genitales o perineo

La extravasación de orina puede provocar edema en el periné, el escroto y los muslos, así como a lo largo de la pared abdominal, entre la fascia transversalis y el peritoneo parietal.

Estudios de imagen

Las indicaciones absolutas para la obtención de imágenes de la vejiga tras un traumatismo abdominal se limitan a la hematuria macroscópica asociada a una fractura pélvica. Las indicaciones relativas para la obtención de imágenes tras un traumatismo abdominal cerrado son los coágulos vesicales, el hematoma perineal y los antecedentes de aumento del tamaño vesical. En los pacientes con lesiones vesicales abiertas, deben realizarse estudios de imagen siempre que exista sospecha de que la vejiga ha sido lesionada o se observe líquido peritoneal libre en la tomografía computarizada (TC) inicial.12,13,6

Cistografía retrógrada

La cistografía retrógrada representa el procedimiento diagnóstico de elección en las lesiones vesicales y siempre debe realizarse en pacientes hemodinámicamente estables o estabilizados con sospecha de lesión vesical. La cistografía por TC ha desplazado a la cistografía convencional para este propósito, y alcanza una sensibilidad del 95% y una especificidad del 100%.

Tomografía computarizada con contraste intravenoso en fase tardía

La tomografía computarizada con contraste intravenoso y fase tardía es menos sensible y específica que la cistografía retrógrada para detectar lesiones vesicales.

Inspección directa de la vejiga intraperitoneal

La inspección directa de la vejiga intraperitoneal debe realizarse, siempre que sea factible, durante la laparotomía de emergencia en pacientes con sospecha de lesión vesical. Los colorantes intravenosos como el azul de metileno o el índigo carmín pueden facilitar la evaluación intraoperatoria.14,15,16

La asociación de fractura pélvica y hematuria macroscópica constituye una indicación absoluta de cistografía inmediata en pacientes con traumatismo contuso. En cambio, puede omitirse la cistografía en pacientes con hematuria aislada si no hay signos físicos de lesiones del tracto urinario inferior.

Un método de imagen potencialmente útil que no está disponible en todos los centros, y menos aún durante las emergencias, es la urosonografía o ecocistografía. Esta opción tiene una alta sensibilidad y especificidad y evita los inconvenientes de la radiación.

El estudio se realiza al mismo tiempo que la evaluación de otras lesiones abdominales y como primera maniobra diagnóstica.17

Tratamiento

La estabilización del paciente y la evaluación de las lesiones asociadas son las prioridades. También es necesaria la administración de antibióticos para evitar infecciones que podrían conducir a sepsis.

El tratamiento quirúrgico de las perforaciones vesicales ha sido y sigue siendo un tema controvertido.18

Lesiones extraperitoneales

La mayoría de las lesiones extraperitoneales pueden tratarse mediante drenaje con catéter uretral. Lo importante es vigilar el funcionamiento del catéter para evitar la obstrucción; si se produce obstrucción, debe realizarse un lavado cuidadoso. Un enfoque eficaz para evitar la obstrucción es colocar un catéter de triple luz con irrigación continua. En los niños, sin embargo, esta posibilidad no existe, dado el calibre de los catéteres de triple luz disponibles en el mercado; por lo tanto colocamos un catéter uretrovesical de un calibre apropiado para la edad del niño y suficiente para permitir irrigación continua, con el uso de un catéter suprapúbico de mayor calibre para el drenaje. El catéter puede lavarse y aspirarse para evitar la obstrucción si es necesario Los catéteres uretrales de mayor calibre pueden provocar estenosis uretrales a largo plazo.

Con este enfoque no quirúrgico, la tasa de corrección es del 90 %, y el 87 % de las lesiones se han resuelto a los 10 días. Cabe señalar que, cuando se observa una espícula ósea sobresaliendo de la vejiga o localizada dentro de ella, y en el caso de laceraciones del cuello, la intervención quirúrgica es obligatoria.

No debe olvidarse la asociación de las lesiones extraperitoneales con las lesiones uretrales. Para descartar estas últimas, debe realizarse una cistouretrografía. El tratamiento quirúrgico es una urgencia, con anastomosis uretrovesical protegida por drenaje perivesical y una sonda vesical.19

Lesiones intraperitoneales

La mayoría de las lesiones intraperitoneales cerradas se localizan en la cúpula vesical. Suelen ser grandes y, a veces, no pueden evaluarse radiológicamente.

En principio, el tratamiento debe ser conservador, con la colocación de un catéter uretrovesical durante 8–10 días. En caso de persistencia de la rotura, complicaciones infecciosas o asociación con otras lesiones graves, se debe considerar la cirugía. El tratamiento quirúrgico solo se justifica si el drenaje vesical es inadecuado o prolongado a través del drenaje peritoneal y/o si no hay mejoría clínica.

Las lesiones vesicales intraperitoneales ocurren tras una fuerza de gran magnitud, con la consiguiente rotura vesical importante. Estas lesiones suelen asociarse a otras lesiones abdominales, que requieren exploración quirúrgica.

El tratamiento quirúrgico se indica con mayor frecuencia en los niños porque el menor calibre de los catéteres uretrales utilizados en los niños (mencionado anteriormente) dificulta un drenaje urinario eficaz y, por lo tanto, la resolución de las lesiones, y porque existe una mayor probabilidad de inestabilidad hemodinámica.20,21,22

Lesiones iatrogénicas

La mayoría de las lesiones iatrogénicas pueden ocurrir en el contexto de cualquier procedimiento quirúrgico, ya sea pélvico, abdominal o vaginal. En estos casos, el reconocimiento de la lesión ocurre intraoperatoriamente, por lo que debe corregirse en ese momento.

Declaraciones de tratamiento

- La contusión vesical no requiere tratamiento específico y puede observarse clínicamente.

- La rotura vesical intraperitoneal debe tratarse mediante exploración quirúrgica y reparación primaria.

- Puede considerarse la laparoscopia para la reparación de lesiones intraperitoneales aisladas en casos con estabilidad hemodinámica y sin otras indicaciones de laparotomía.

- En casos de rotura vesical intraperitoneal grave, durante procedimientos de control de daños, puede emplearse derivación urinaria mediante drenaje vesical y perivesical o tutorización ureteral externa.

- Las lesiones vesicales extraperitoneales por traumatismo cerrado o penetrante no complicadas pueden manejarse de forma no operatoria, con drenaje urinario mediante sonda uretral o suprapúbica en ausencia de cualquier otra indicación de laparotomía.

- Las roturas vesicales extraperitoneales complejas, es decir, lesiones del cuello vesical, lesiones asociadas a fractura del anillo pélvico y/o lesiones vaginales o rectales, deben explorarse y repararse.

- Debe considerarse la reparación quirúrgica de la rotura vesical extraperitoneal durante la laparotomía por otras indicaciones y durante la exploración quirúrgica del espacio prevesical para fijaciones ortopédicas.

- En pacientes adultos, el drenaje urinario mediante sonda uretral (sin sonda suprapúbica) tras el manejo quirúrgico de las lesiones vesicales es obligatorio. En pacientes pediátricos, se recomienda cistostomía suprapúbica.6

Seguimiento

Debido a que el objetivo es cerrar la rotura vesical, el catéter vesical se mantiene en su lugar durante 9–11 días en casos de tratamiento conservador, mientras que en pacientes que han sido sometidos a corrección quirúrgica, 7 días pueden ser suficientes. Sin embargo, antes de retirar el catéter vesical, debe realizarse una cistografía para comprobar que no haya extravasación. Si se ha utilizado un catéter suprapúbico, primero se pinza y, si no hay problemas con la micción, luego se retira, valorando asimismo si existe residuo posmiccional.22

Complicaciones

Las complicaciones son más frecuentes en los casos con retraso en el diagnóstico y, por lo tanto, en el tratamiento. Las más frecuentes son el hematoma, las infecciones, la peritonitis y la sepsis.

Pueden presentarse fístulas urinarias, y su persistencia requiere endoscopia. Según el resultado, el tratamiento será mediante maniobras endoscópicas o cirugía abierta.21

Traumatismo ureteral

Epidemiología y diagnóstico

Las lesiones ureterales son raras (menos del 1%). La causa más frecuente de lesión ureteral es el traumatismo penetrante, en especial las heridas por arma de fuego; solo un tercio de los casos se debe a traumatismo contuso. En el traumatismo contuso, las lesiones ureterales ocurren con frecuencia en la unión ureteropélvica, especialmente en niños y en lesiones por desaceleración de alta energía. Las lesiones de órganos asociadas son comunes en pacientes con lesiones ureterales. La presentación clínica de las lesiones ureterales puede ser sutil, pero la hematuria aislada es un hallazgo frecuente.23

Debe sospecharse lesión del uréter en los pacientes que han sufrido traumatismo contuso de alta energía, particularmente en presencia de lesiones por desaceleración con afectación multisistémica y en casos de traumatismo abdominal penetrante.24

La estriación de la grasa perirrenal o los hematomas, la extravasación de contraste al espacio perirrenal y la presencia, en las imágenes, de líquido retroperitoneal de baja atenuación alrededor de los elementos genitourinarios son indicativos de lesiones ureterales. La hematuria macroscópica o microscópica no es un signo fiable de lesión ureteral porque está ausente en hasta el 25 % de los casos. Un retraso en el diagnóstico puede tener un impacto negativo en los desenlaces. La ecografía no tiene ningún papel en el diagnóstico de la lesión ureteral. En la TC en fase tardía, el hematoma periureteral, la obstrucción parcial o completa de la luz, la discreta distensión del uréter, la hidronefrosis, el pielograma tardío y la ausencia de contraste en el uréter distal a la lesión son signos sugestivos de lesión ureteral. La ascitis urinaria y el urinoma se consideran hallazgos subagudos/crónicos. Una TC con fase tardía a los 10 min constituye una herramienta diagnóstica válida en el diagnóstico de lesiones ureterales y ureteropélvicas.25,26

Si los resultados de la tomografía computarizada no son concluyentes, la pielografía retrógrada representa el método de elección. La urografía intravenosa (IVU) es una prueba poco fiable (con una tasa de falsos negativos de hasta el 60%).27

Si se requiere una laparotomía de urgencia, está indicada la inspección directa del uréter, y puede asociarse al uso de un colorante intravenoso de excreción renal (es decir, índigo carmín o azul de metileno). Una UIV de una sola toma puede estar indicada intraoperatoriamente.

La sospecha de lesión ureteral es crucial en cualquier niño con traumatismo abdominal de alta energía que presente múltiples lesiones concomitantes. Asimismo, aunque las lesiones ureterales traumáticas son raras, cualquier lesión causada por traumatismo penetrante debe hacer sospechar una lesión ureteral.

La tomografía computarizada (TC) es el mejor método para diagnosticar el traumatismo ureteral. Ya en la fase excretora, puede no mostrar el paso de contraste hacia el uréter distal, lo que puede llevar a sospechar una avulsión ureteral.

Aunque una pielografía retrógrada es probablemente el método más preciso para evaluar la integridad ureteral, [no es práctico en un entorno de trauma agudo]{:.text-decoration-underline}.

También se puede realizar una evaluación intraoperatoria mediante inspección directa del uréter con la ayuda de una inyección de azul de metileno por vía urinaria o mediante administración parenteral de índigo carmín.28,29

Tratamiento

El tipo de tratamiento depende de la clasificación adecuada de la lesión del órgano, del estado general del paciente, del tiempo transcurrido desde el diagnóstico y de la localización de la lesión.

Si la lesión ureteral se reconoce de forma precoz, el uréter debe repararse de inmediato (anastomosis sin tensión con espatulación de ambos extremos). Si es posible, el sitio de la anastomosis también debe recubrirse con grasa retroperitoneal u omento. Se recomienda la colocación de una derivación urinaria (nefrostomía o stent ureteral).

Debido a que la mayoría de las lesiones ureterales se diagnostican tarde, la reparación inmediata durante la exploración abdominal es diagnosticada. Los tratamientos “mínimamente invasivos” se han vuelto cada vez más populares en este contexto. Se ha demostrado que el drenaje percutáneo de urinomas y la colocación de un tubo de nefrostomía son útiles en casos de traumatismo cerrado y penetrante del uréter. La cateterización ureteral sin cirugía abierta también se ha utilizado con éxito.

El manejo de las contusiones ureterales no requiere tratamiento activo salvo que exista necrosis tisular, en cuyo caso están indicados la cateterización ureteral y el drenaje periureteral.30

Las laceraciones ureterales parciales pueden ser candidatas a reparación primaria o tratamiento con un catéter ureteral. El manejo de las laceraciones completas y las avulsiones dependerá de la cantidad de uréter perdido y de su localización. Si existe una longitud adecuada de uréter sano, la realización de una uretero-ureterostomía tras el desbridamiento de la herida puede ser una opción. De lo contrario, la cirugía reconstructiva es la elección adecuada y, en el caso de lesiones proximales, la transuretero-ureterostomía, el autotrasplante y el reemplazo ureteral con intestino o apéndice parecen opciones razonables.

Si el estado general del paciente impide una reparación inmediata, una ureterostomía temporal con tratamiento reconstructivo en una segunda etapa es una opción que proporciona un buen drenaje sin necesidad de sondas.

Las avulsiones de la unión ureteropélvica deben manejarse con una reanastomosis primaria si es posible. Si la longitud ureteral es inadecuada, la ureterocalicostomía es una opción adecuada.30

Declaraciones de tratamiento

- Las contusiones pueden requerir la colocación de un stent ureteral cuando el flujo urinario está comprometido.

- Las lesiones parciales del uréter deben tratarse inicialmente de forma conservadora con el uso de un stent, con o sin nefrostomía de derivación, en ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía.

- Las transecciones o avulsiones ureterales, parciales y completas, no aptas para manejo no operatorio pueden tratarse con reparación primaria más un stent doble J o con reimplante ureteral en la vejiga en el caso de lesiones distales.

- Las lesiones ureterales deben repararse de forma quirúrgica cuando se descubren durante una laparotomía o en casos en los que ha fracasado el manejo conservador.

- Debe intentarse la colocación de un stent ureteral en los casos de lesiones parciales del uréter diagnosticadas de forma tardía; si este enfoque falla y/o en casos de transección completa del uréter, está indicada la nefrostomía percutánea con reparación quirúrgica diferida.

- En cualquier reparación ureteral, se recomienda encarecidamente la colocación de un stent.24

Complicaciones

La extravasación urinaria puede presentarse como una masa en crecimiento en el flanco abdominal, sin signos de sangrado. El manejo inicial debe incluir una derivación urinaria, con la colocación de un catéter doble J o de un catéter de nefrostomía percutánea. Si ya existe un urinoma y/o un absceso, puede drenarse percutáneamente. La mayoría de los casos evolucionan sin la formación de una estenosis ureteral.31

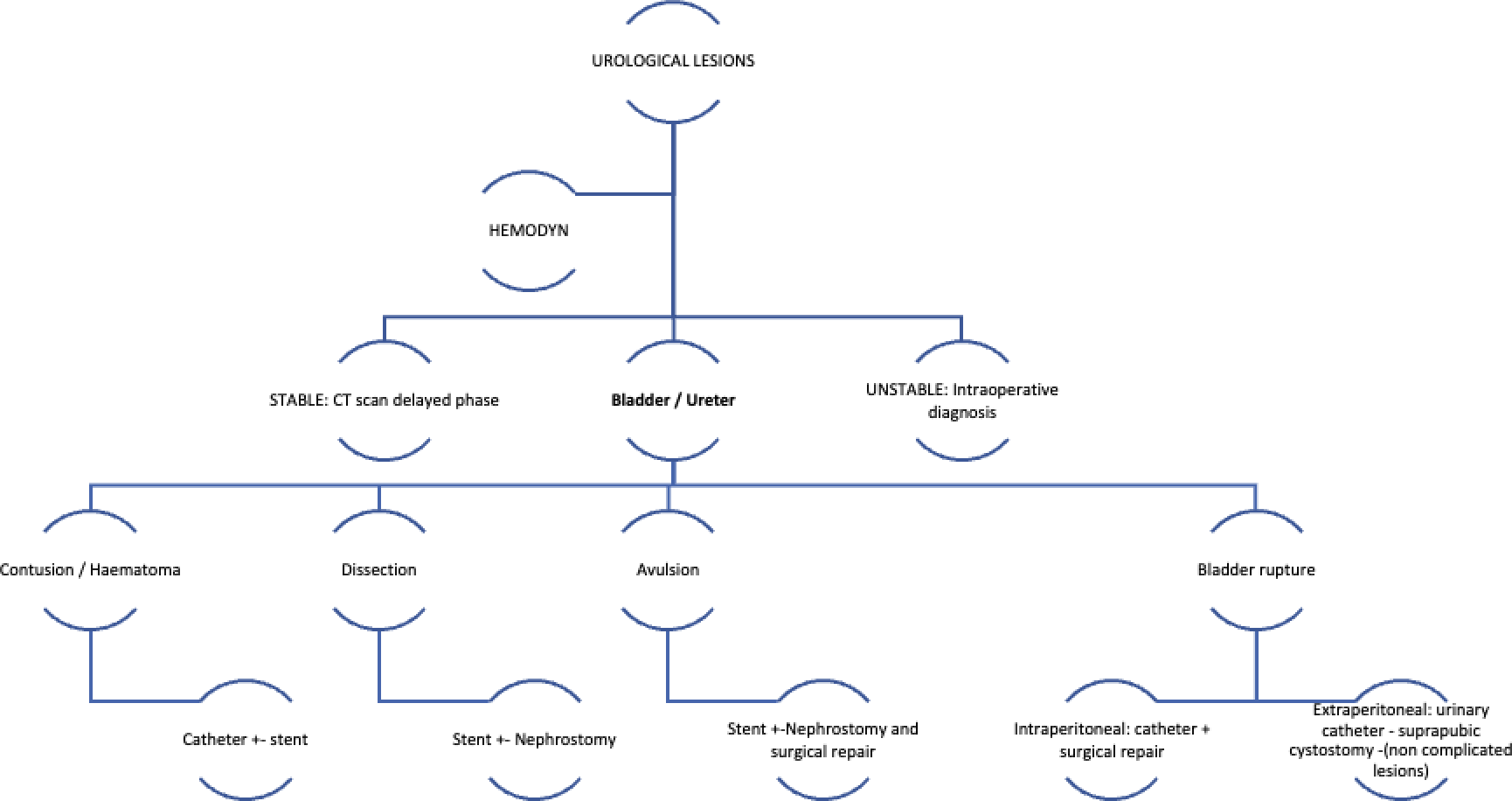

Figura 1 Tipos de lesiones vesicales y ureterales y su manejo6,24

Tabla 1 Guías para el manejo del trauma ureteral.

| Recomendación | Nivel de evidencia |

|---|---|

| Las contusiones pueden requerir la colocación de un stent ureteral cuando el flujo de orina está comprometido. | 1C |

| Las lesiones parciales del uréter deben tratarse inicialmente de forma conservadora con el uso de un stent, con o sin nefrostomía derivativa, en ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía. | 1C |

| Las transecciones o avulsiones ureterales parciales y completas no adecuadas para manejo no operatorio pueden tratarse con reparación primaria más un stent doble J o con reimplante ureteral en la vejiga en caso de lesiones distales. | 1C |

| Las lesiones ureterales deben repararse de forma quirúrgica cuando se descubran durante una laparotomía o en casos en los que el manejo conservador haya fracasado. | 1C |

| Debe intentarse la colocación de un stent ureteral en casos de lesiones ureterales parciales diagnosticadas de forma tardía; si esta estrategia fracasa y/o en caso de transección completa del uréter, está indicada una nefrostomía percutánea con reparación quirúrgica diferida. | 1C |

| En cualquier reparación ureteral, se recomienda firmemente la colocación de un stent. | 1C |

En ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía, la mayoría de las lesiones ureterales de bajo grado (contusión o transección parcial) pueden manejarse mediante observación y/o colocación de un stent ureteral. Si la colocación del stent no tiene éxito, se debe colocar un tubo de nefrostomía.

Si se sospechan lesiones ureterales durante una laparotomía, la visualización directa del uréter es obligatoria. Siempre que sea posible, las lesiones ureterales deben repararse. De lo contrario, debe preferirse una estrategia de control de daños, con ligadura del uréter lesionado y derivación urinaria (nefrostomía temporal), seguida de reparación diferida.

En casos de sección completa del uréter, está indicada la reparación quirúrgica. Las dos opciones principales son la uretero-ureterostomía primaria o el reimplante ureteral con suspensión vesical al psoas o un colgajo de Boari. Se recomienda el uso de stents ureterales tras todas las reparaciones quirúrgicas para reducir los fracasos (fugas) y las estenosis. Las lesiones distales del uréter (caudales a los vasos ilíacos) suelen tratarse mediante reimplante del uréter en la vejiga (ureteroneocistostomía), ya que la agresión traumática puede comprometer el riego sanguíneo.

En casos de diagnóstico tardío de lesiones ureterales incompletas o de presentación tardía, se debe intentar la colocación de un stent ureteral; sin embargo, la colocación retrógrada del stent suele ser infructuosa. En estos casos, se debe considerar la reparación quirúrgica diferida (32)

Tabla 2 Directrices para el manejo de la lesión vesical.

| Recomendación | Nivel de evidencia |

|---|---|

| La contusión vesical no requiere tratamiento específico y puede observarse clínicamente | 1C |

| La rotura vesical intraperitoneal debe manejarse mediante exploración quirúrgica y reparación primaria | 1B |

| Puede considerarse la laparoscopia para la reparación de lesiones intraperitoneales aisladas en casos de estabilidad hemodinámica y ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía. | 2B |

| En casos de rotura vesical intraperitoneal grave, durante procedimientos de control de daños, puede emplearse la derivación urinaria mediante drenaje vesical y perivesical o la colocación de un stent ureteral externo. | 1C |

| Las lesiones vesicales extraperitoneales contusas o penetrantes no complicadas pueden manejarse de manera no operatoria, con drenaje urinario mediante sonda uretral o suprapúbica, en ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía. | 1C |

| Las roturas vesicales extraperitoneales complejas, es decir, lesiones del cuello vesical, lesiones asociadas a fractura del anillo pélvico y/o lesiones vaginales o rectales, deben explorarse y repararse. | 1C |

| Debe considerarse la reparación quirúrgica de la rotura vesical extraperitoneal durante una laparotomía por otras indicaciones y durante la exploración quirúrgica del espacio prevesical para fijaciones ortopédicas. En casos de inestabilidad hemodinámica, puede colocarse una sonda uretral o suprapúbica como medida temporal y posponerse la reparación de la lesión vesical. | 1C |

En general, todas las lesiones vesicales penetrantes y los casos de rotura vesical intraperitoneal (IBR) requieren exploración quirúrgica y reparación primaria. La reparación laparoscópica de la IBR aislada es una opción viable. La reparación quirúrgica abierta de las lesiones vesicales se realiza en doble capa utilizando sutura monofilamento absorbible. La reparación en una sola capa es común durante un abordaje laparoscópico.

En ausencia de otras indicaciones para laparotomía, las EBR por traumatismo contuso o penetrante no complicadas pueden manejarse de forma conservadora, con observación clínica, profilaxis antibiótica y la colocación de un catéter uretral o de una cistostomía suprapúbica percutánea en los casos de lesión uretral concomitante. La cicatrización de la lesión ocurre en un plazo de 10 días en más del 85% de los casos. La reparación quirúrgica de la EBR está indicada en lesiones complejas como las lesiones del cuello vesical, las lesiones asociadas a fracturas pélvicas que requieren fijación interna y las lesiones rectales o vaginales. Además, puede considerarse la reparación quirúrgica de la EBR en casos de persistencia de la extravasación de orina 4 semanas después del evento traumático.

Las lesiones vesicales por arma de fuego se asocian con frecuencia a lesiones rectales, las cuales ameritan una derivación fecal. Habitualmente, estas lesiones son transfixiantes (orificio de entrada/salida), por lo que requieren una exploración pélvica cuidadosa y completa.

La cateterización uretral, siempre que sea posible, tiene la misma eficacia que la cistostomía suprapúbica; por lo tanto, ya no se recomienda la colocación rutinaria de una sonda suprapúbica. La cateterización suprapúbica puede reservarse para pacientes con lesiones perineales asociadas. Se recomienda el drenaje suprapúbico en niños tras la reparación quirúrgica de la ruptura vesical.6

Puntos clave: traumatismo vesical

- La incidencia de la rotura vesical durante la infancia es baja, y esta entidad representa alrededor del 5% de las lesiones del tracto urinario.

- Las lesiones vesicales son principalmente de cuatro tipos: rotura vesical intraperitoneal (IBR), rotura vesical extraperitoneal (EBR), contusión vesical y avulsión del cuello vesical. La IBR ocurre en el 15–25% de los casos y la EBR es el tipo más común, encontrándose en el 60–90% de los pacientes, y se asocia con mayor frecuencia a fracturas pélvicas.

- Las indicaciones absolutas para realizar estudios de imagen de la vejiga después de un traumatismo abdominal se limitan a la hematuria macroscópica asociada a una fractura pélvica.

- La estabilización del paciente y la evaluación de las lesiones asociadas son las prioridades.

- La contusión vesical no requiere tratamiento específico y puede observarse clínicamente.

- La rotura vesical intraperitoneal debe tratarse mediante exploración quirúrgica y reparación primaria.

- Las lesiones vesicales extraperitoneales contusas o penetrantes no complicadas pueden manejarse de forma no operatoria, con drenaje urinario mediante un catéter uretral o suprapúbico en ausencia de cualquier otra indicación para laparotomía.

- Las roturas vesicales extraperitoneales complejas, es decir, lesiones del cuello vesical, lesiones asociadas con fractura del anillo pélvico y/o lesiones vaginales o rectales, deben explorarse y repararse.

Puntos clave: Traumatismo ureteral

- Las lesiones ureterales traumáticas son poco frecuentes (menos de 1%).

- La causa más frecuente de lesión ureteral es el trauma penetrante, especialmente las heridas por arma de fuego; solo un tercio de los casos se debe a trauma contuso.

- La estriación de la grasa perirrenal o los hematomas, la extravasación de contraste hacia el espacio perirrenal y la presencia de líquido retroperitoneal de baja densidad alrededor de los elementos genitourinarios en las pruebas de imagen son indicativos de lesiones ureterales.

- La tomografía computarizada (TC) es el mejor método para diagnosticar el trauma ureteral. Ya en la fase excretora, puede no mostrar el paso de contraste hacia el uréter distal, lo que puede hacer sospechar una avulsión ureteral.

- Las contusiones pueden requerir la colocación de un stent ureteral cuando el flujo urinario está comprometido.

- Las lesiones parciales del uréter deben tratarse inicialmente de forma conservadora mediante el uso de un stent, con o sin nefrostomía derivativa, en ausencia de otras indicaciones de laparotomía.

- Las secciones o avulsiones ureterales parciales y completas no susceptibles de manejo no quirúrgico pueden tratarse con reparación primaria más un catéter doble J o reimplante ureteral en la vejiga en el caso de lesiones distales.

- Las lesiones ureterales deben repararse quirúrgicamente cuando se descubren durante una laparotomía o en los casos en que el manejo conservador ha fracasado.

Referencias

- Husman D. Traumatismo genitourinario pediátrico. In: J WA, R KL, W PA, A PC, editors. Cambell-Walsh, vol. 132. 9a ed. Carroll PR, Mcaninch JW: J Urol; 2007. DOI: 10.4067/s0370-41062000000500014.

- Djakovic N, Plas E, Piñeiro LM, Th. Lynch YM, Santucci RA, Serafetinidis E, et al.. Guía de consenso sobre los contenidos de los protocolos de ensayos clínicos. Medicina Clínica 2010; 141 (4): 161–162. DOI: 10.1016/j.medcli.2013.01.033.

- Armenakas NA, Pareek G, Fracchia JA. Iatrogenic bladder perforations: longterm followup of 65 patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2004; 198 (1): 78–82. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2003.08.022.

- Dobrowolski ZF, Lipczyñski W, Drewniak T, Jakubik P, Kusionowicz J. External and iatrogenic trauma of the urinary bladder: a survey in Poland. BJU International 2002; 89 (7): 755–756. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02718.x.

- Schneider RE. Genitourinary Trauma. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 1993; 11 (1): 137–145. DOI: 10.1016/s0733-8627(20)30663-5.

- En GJMT, M GJ, R G. "Xxiv Congress Sociedad Iberoamericana De Urología Pediátrica (Siup) ". Xxiv Congress Sociedad Iberoamericana De Urología Pediátrica (Siup) 1987: 529–530. DOI: 10.3389/978-2-88963-089-9.

- Stein RJ, Matoka DJ, Noh PH, Docimo SG. Spontaneous perforation of congenital bladder diverticulum. Urology 2005; 66 (4): 881.e5–881.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.04.004.

- Crandall ML, Agarwal S, Muskat P, Ross S, Savage S, Schuster K, et al.. Application of a uniform anatomic grading system to measure disease severity in eight emergency general surgical illnesses. Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 2014; 77 (5): 705–708. DOI: 10.1097/ta.0000000000000444.

- Bakal U, Sarac M, Tartar T, Ersoz F, Kazez A. Bladder perforations in children. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 2015; 18 (4): 483. DOI: 10.4103/1119-3077.151752.

- Hwang EC, Kwon DD, Kim CJ, Kang TW, Park K, Ryu SB, et al.. Eosinophilic cystitis causing spontaneous rupture of the bladder in a child Int J Urol. 2006; 13 (4): 449–450. DOI: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2006.01320.x.

- Giutronich S, Scalabre A, Blanc T, Borzi P, Aigrain Y, O’Brien M, et al.. Spontaneous bladder rupture in non-augmented bladder exstrophy. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2016; 12 (6): 400.e1–400.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.04.054.

- Morgan DE, Nallamala LK, Kenney PJ, Mayo MS, Rue LW. CT Cystography. American Journal of Roentgenology 2000; 174 (1): 89–95. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.174.1.1740089.

- Abou-Jaoude WA, Sugarman JM, Fallat ME, Casale AJ. Indicators of genitourinary tract injury or anomaly in cases of pediatric blunt trauma. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 1996; 31 (1): 86–90. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(96)90325-5.

- Morey AF, Iverson AJ, Swan A, Harmon WJ, Spore SS, Bhayani S, et al.. Bladder Rupture after Blunt Trauma: Guidelines for Diagnostic Imaging. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care 2001; 51 (4): 683–686. DOI: 10.1097/00005373-200110000-00010.

- Horstman WG, McClennan BL, Heiken JP. Comparison of computed tomography and conventional cystography for detection of traumatic bladder rupture. Urologic Radiology 1991; 12 (1): 188–193. DOI: 10.1007/bf02924005.

- Morey AF, Hernandez J, McAninch JW. Reconstructive surgery for trauma of the lower urinary tract. Urologic Clinics of North America 1999; 26 (1): 49–60. DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(99)80006-8.

- Deck AJ, Shaves S, Talner L, Porter JR. Computerized Tomography Cystography For The Diagnosis Of Traumatic Bladder Rupture. The Journal of Urology 2000; 64 (1): 43–46. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200007000-00011.

- Shin SS, Jeong YY, Chung TW, Yoon W, Kang HK, Kang TW, et al.. The Sentinel Clot Sign: a Useful CT Finding for the Evaluation of Intraperitoneal Bladder Rupture Following Blunt Trauma. Korean Journal of Radiology 2007; 8 (6): 492. DOI: 10.3348/kjr.2007.8.6.492.

- Karmazyn B. CT cystography for evaluation of augmented bladder perforation: be safe and know the limitations. Pediatric Radiology 2016; 46 (4): 579–579. DOI: 10.1007/s00247-015-3501-y.

- Kessler DO, Francis DL, Esernio-Jenssen D, D.. Bladder Rupture After Minor Accidental Trauma. Pediatric Emergency Care 2010; 26 (1): 43–45. DOI: 10.1097/pec.0b013e3181c8c5f2.

- Chan DPN, Abujudeh HH, Cushing GL, Novelline RA. CT Cystography with Multiplanar Reformation for Suspected Bladder Rupture: Experience in 234 Cases. American Journal of Roentgenology 2006; 187 (5): 1296–1302. DOI: 10.2214/ajr.05.0971.

- Hayes EE, Sandler CM, Corriere JN. Management of the Ruptured Bladder Secondary to Blunt Abdominal Trauma. Journal of Urology 1983; 129 (5): 946–947. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)52472-6.

- JN C Jr, CM S. Management of the ruptured bladder: seven years of experience with 111 cases J Trauma. 1986; 26 (9): 830–833. DOI: 10.1097/00005373-198609000-00009.

- Parra RO. Laparoscopic Repair of Intraperitoneal Bladder Perforation. Journal of Urology 1994; 151 (4): 1003–1005. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35150-9.

- Osman Y, El-Tabey N, Mohsen T, El-Sherbiny M. Nonoperative Treatment Of Isolated Posttraumatic Intraperitoneal Bladder Rupture In Children—is It Justified? Journal of Urology 2005; 173 (3): 955–957. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152220.31603.dc.

- Bhanot A, Bhanot A. Laparoscopic Repair in Intraperitoneal Rupture of Urinary Bladder in Blunt Trauma Abdomen. Surgical Laparoscopy, Endoscopy &Amp; Percutaneous Techniques 2007; 17 (1): 58–59. DOI: 10.1097/01.sle.0000213760.55676.47.

- Tander B, Karadag CA, Erginel B, Demirel D, Bicakci U, Gunaydin M, et al.. Laparoscopic repair in children with traumatic bladder perforation. Journal of Minimal Access Surgery 2016; 12 (3): 292. DOI: 10.4103/0972-9941.169973.

- Coccolini F, Moore EE, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Leppaniemi A, Matsumura Y, et al.. Kidney and uro-trauma: WSES-AAST guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2019; 14 (1): 1–25. DOI: 10.1186/s13017-019-0274-x.

- McAleer IM, Kaplan GW, Scherz HC, Packer MG, P.Lynch F. Genitourinary trauma in the pediatric patient. Urology 1993; 42 (5): 563–567. DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(93)90274-e.

- Coccolini F, Moore EE, Kluger Y, Biffl W, Leppaniemi A, Matsumura Y, et al.. Kidney and uro-trauma: WSES-AAST guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery 2019; 14 (1): 1–25. DOI: 10.1186/s13017-019-0274-x.

- McGahan JP, Rose J, Coates TL, Wisner DH, Newberry P. Use of ultrasonography in the patient with acute abdominal trauma. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 1997; 16 (10): 653–662. DOI: 10.7863/jum.1997.16.10.653.

- Mutabagani KH, Coley BD, Zumberge N, McCarthy DW, Besner GE, Caniano DA, et al.. Preliminary experience with focused abdominal sonography for trauma (FAST) in children: Is it useful? Journal of Pediatric Surgery 1999; 34 (1): 48–54. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90227-0.

- Buckley JC, McAninch JW. Revision of Current American Association for the Surgery of Trauma Renal Injury Grading System. Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection &Amp; Critical Care 2011; 70 (1): 35–37. DOI: 10.1097/ta.0b013e318207ad5a.

- Buckley JC, Mcaninch JW. Pediatric Renal Injuries: Management Guidelines From A 25-year Experience. Journal of Urology 2004; 172 (2): 687–690. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000129316.42953.76.

- Broghammer JA, Langenburg SE, Smith SJ, Santucci RA. Pediatric blunt renal trauma: Its conservative management and patterns of associated injuries. Urology 2006; 67 (4): 823–827. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.062.

- Wright JL, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Wessells H. Renal and Extrarenal Predictors of Nephrectomy from the National Trauma Data Bank. Journal of Urology 2006; 175 (3): 970–975. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)00347-2.

- Armenakas NA. Ureteral Trauma: Surgical Repair. Atlas of the Urologic Clinics 1998; 6 (2): 71–84. DOI: 10.1016/s1063-5777(05)70167-5.

Última actualización: 2025-09-21 13:35