34: Other Penile Abnormalities

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 16 minutos para leer.

Introduction

This chapter aims to discuss other penile conditions that may be encountered (apart from hypospadias) which may potentially warrant surgical intervention or correction. These include chordee, penile torsion, buried penis and congenital megaprepuce.

Chordee and penile torsion may be associated with hypospadias or other urological conditions; or may be an isolated entity. The term congenital chordee has been used interchangeably as chordee without hypospadias, congenital short urethra and congenital penile curvature throughout literature. Snodgrass proposed that ‘chordee without hypospadias’ be replaced by ‘congenital penile curvature’ and will be referred to as such throughout this chapter.1 There are varying degrees of congenital penile curvature. This can be ventral, dorsal, and lateral or a combination of the three.

Penile torsion is an abnormal rotation of the penile shaft that occurs most frequently in the counterclockwise direction. Congenital penile curvature and penile torsion have also been reported to occur simultaneously.2

There are varied presentations of the buried penis or congenital megaprepuce. These conditions can vary in the spectrum they present and are commonly confused with micropenis, however, the size of the penis is usually normal. A presenting complaint may be difficulty with voiding as a result of urine entrapment in boys with a congenital megaprepuce. There are many terms and descriptors that have been used to describe the condition: hidden, concealed, inconspicuous, invisible, entrapped, and buried penis amongst others. These broad encompassing terms correlate to describing the appearance of the penis but may not be the defining the anatomical cause.3 As with its nomenclature, many approaches for its correction have been documented.

Embryology

During its growth, the external genitalia develops swiftly which can result in large morphological variations.4 Between the 4th and 7th weeks of gestation, the genital tubercle is formed by migration of mesodermal mesenchyme to the cranial region of the cloacal membrane. The caudal region of the cloacal membrane forms the urogenital folds. The cloacal membrane is a dual-layered structure, having an endoderm and an ectoderm. From the 7th week of gestation, external genital differentiation in the male sex occurs. This is completed by 16–17 weeks of gestation. The SRY gene on the Y chromosome signals the development of the primitive sex cords to form testes. Leydig cells within the testes produce testosterone which is converted to dihydrotestosterone to promote development of external genitalia of males.5

In the male, androgens cause the mesoderm of the genital tubercle to form the corpora cavernosa and glans penis. The proximal penile urethra is a result of tubularization of the endoderm. This is in comparison to the distal penile urethra that occurs as a result of recanalisation.6 During the 8th week of gestation, the ectoderm develops into penile skin and prepuce. Bellinger and Kaplan demonstrated that penile curvature is a normal state of development, with resolution by the 16th week of gestation,7,8

Congenital Penile Curvature

History

Nesbit first described three cases of congenital penile curvature in 1965. He suggested that this condition was secondary to disproportionate fascial lengths surrounding the corporal bodies.9

Congenital penile torsion was first described by Verneuil in 1857. At the time, operative intervention was advised against as attempts to mobilise skin were unsuccessful in correcting the spiral alignment of the corpora cavernosa. Fevre described a technique for repair of penile torsion in 1947, where he removed the crura from the pubis and reinserted them into a normal position.10,11

Epidemiology

Early papers have noted that congenital penile curvature occurs in 4–10% of males.12,13 The incidence of dorsal curvature is low in the absence of hypospadias, with rates of ~5% being described.14

The incidence of congenital penile torsion ranges from 1.5–27%.15,16 Significant penile torsion of more than 90 degrees is less frequent, affecting 0.7% of newborn males.16

Pathogenesis

In 1937, Young theorised that penile curvature was secondary to a congenitally short urethra. Abnormal development of periurethral fascia was proposed by Devine and Horton as a cause.17 Kramer proposed that corporal body disproportion was the contributor to penile curvature.13 In their series, Donnahoo noted penile curvature secondary to tethering of skin and dartos as the most common cause (65%), corporeal body disproportion (28%), and a congenitally shortened urethra (7%). This study noted rates of ventral (84%), dorsal (11%), and lateral (5%) curvature.12 Histopathological study of the urethral plate demonstrated the absence of fibrosis and dysplasia in samples taken intraoperatively.18 This evidence however, refutes the theory of fibrous bands causing penile curvature. Arrest in penile development whilst the penis has a physiological curve has also been proposed as a cause to persistent penile curvature.7

Acquired dorsal curvature may occur as a result of scar contraction or abnormal scarring following a circumcision.19

The exact aetiology of congenital penile torsion is unknown. Proposed theories include abnormal skin attachment, asymmetric development of corpora cavernosa, and rotational defect of either the corporal bodies or the glans.11,20

Evaluation and Diagnosis

In the male with hypospadias, the presence of congenital penile curvature and torsion is frequently assessed intra-operatively following an artificial erection test.

In children without hypospadias, it is often parental observation that raises the concern of penile curvature. During adolescence, penile curvature becomes evident following natural erections. Another instance that may lead to the detection of these conditions is as an incidental finding during a routine medical examination. Torsion may be suspected if the penile raphae deviates from the midline. The presence of these conditions, however, is less obvious in children with a physiological phimosis. Assessment in the clinic can also be limited by poor patient cooperation and body habitus.19 Intraoperative assessment of penile curvature is achieved by an artificial erection test.

An operative classification of congenital penile curvature was proposed by Devine and Horton into three categories. Group I, secondary to deficient corpus spongiosum, dartos, and Buck fascia; Group II due to deficient dartos and Buck fascia; and Group III involved only dartos fascia.17 This classification system was expanded upon to include Group IV which was representative of corporal body disproportion.13 An additional operative classification system by Donnahoo et al described three types of congenital penile curvature; Type I is curvature secondary to skin tethering (Figure 1) and (Figure 2) Type II is due to fascial chordee, and Type III is a result of corporal body disproportion.12

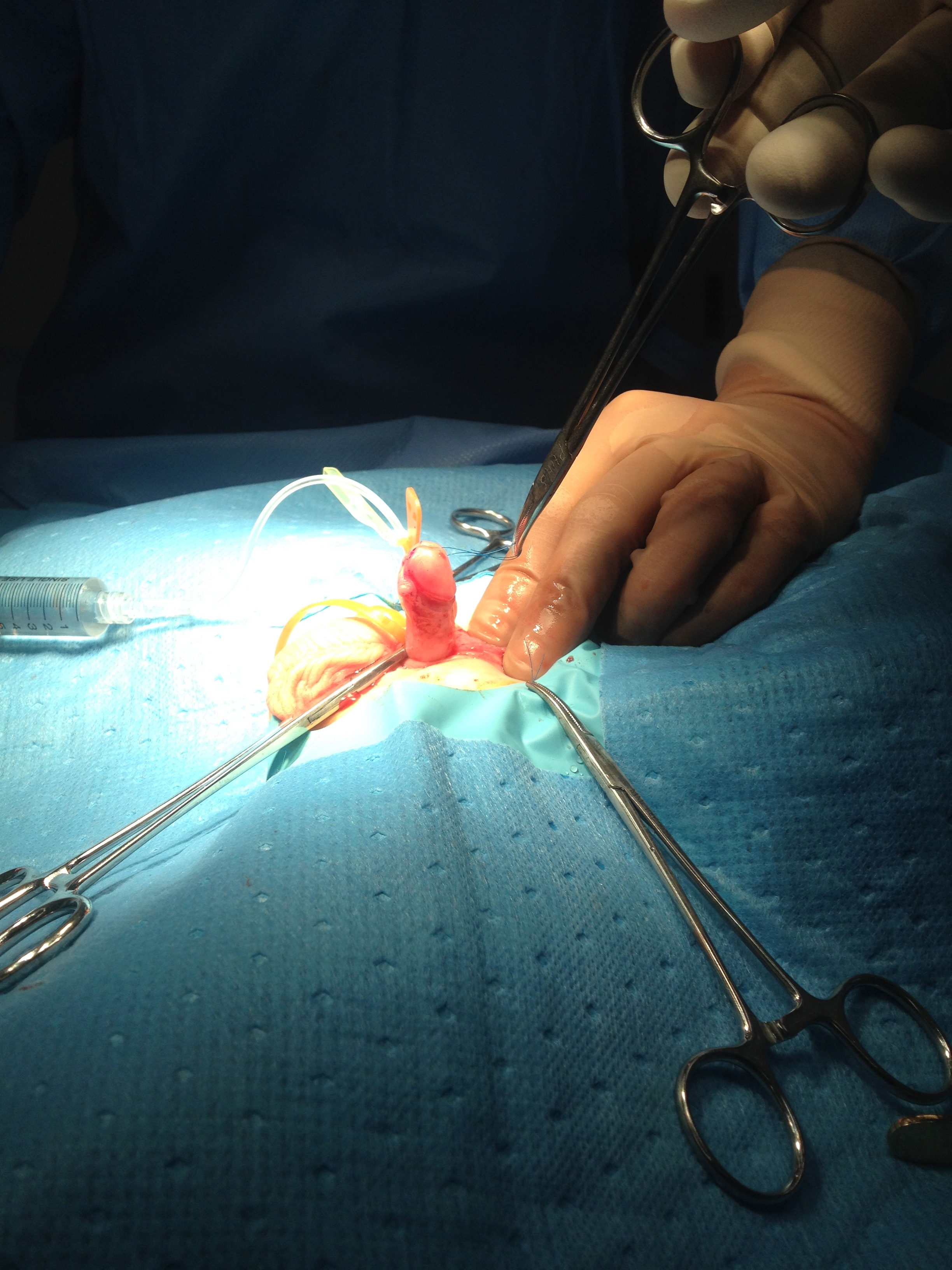

Figure 1 Type 1 curvature with hooded foreskin and apical meatus.

Figure 2 Erection test after degloving showing curvature corrected.

Treatment Options

If diagnosed early, surgical correction of congenital penile curvature should ideally occur during the first year of life.21 The surgical options for managing penile curvature are dependent on the severity, preferably with the least invasive technique attempted initially.19 A survey of paediatric urologists run by AAP, found that penile curvature up to 10 degrees would frequently be left untreated. A penile curvature of more than 20 degrees to 30 degrees requires intervention, hence this severity was labelled as significant chordee.22,23 The survey found that any penile curvature less than 50 degrees was often managed by dorsal plication, whereas curvature greater than 50 degrees would commonly require a ventral lengthening procedure.22

In the presence of glans tilt, an initial frenular release is recommended as a first step. The penis is degloved to its base to address skin tethering. An artificial erection test is performed to demonstrate persistent penile curvature. Plication is suggested for residual penile curvature up to 30 degrees.1 The Nesbit technique was one of the earliest methods to correct penile curvature. This involved dissection of the dorsal neurovascular bundle off the corpora followed by plication of the tunica albuginea to correct the existent length disproportion with the ventral aspect. This technique was later modified after observing a recurrence and involved the excision of a diamond-shaped wedge at the site of maximal curvature and transverse apposition of the tunica edges.9 Neuroanatomical studies demonstrated that nerve branches to the penis are located at 11 and 1 o’clock and spread ventrally.5 Therefore, dorsal midline plication is performed in the 12 o’clock position avoiding the neurovascular bundle. This area is also the thickest and strongest region of the tunica.21,24 Whether a single plication suture or multiple plication sutures are used remains the choice of the surgeon.

There are various techniques to manage penile curvature that is greater than 30 degrees, including urethral plate transection and ventral corporotomy (with or without grafting the corporal defect) and staged urethroplasty.1,13 This provides ventral lengthening to address corporal disproportion. The initial dermal graft was described by Devine and Horton.17

To avoid urethral plate transection, Mollard and Castagnola proposed dissection of the urethra from underlying corpora cavernosa in addition to dorsal plication.25 Similarly, dissection of the urethra from corpora was performed and extended to the bulbar urethra.26

Congenital penile curvature was managed by Donnahoo et al using complete mobilisation of the urethra with ventral dermal grafting.12 This was similar to the experience by Tang in up to a quarter of their patients.23

Other techniques to manage complex presentations of chordee associated with hypospadias or epispadias include corporal body dissociation and penile disassembly and grafting with small intestinal submucosa,27,28,29,30

Modification of preceding Shaeer I and II techniques, involved rotation of the corpora with suture fixation without a corporotomy.31

Correction of penile torsion is argued to be a cosmetic procedure, as the penis remains functionally acceptable. Some authors have advocated for repair of penile torsion if the degree of torsion is more than 45 degrees. There are multiple surgical options for correction of penile torsion. A step-wise operative approach has been proposed which involves penile degloving, broad dartos-based rotation flap, mobilisation of urethral plate and spongiosum, mobilisation of proximal urethra, and mobilisation of urethral plate/hypoplastic urethra with spongiosum into the glans.32,33 An additional method described is lateral suturing of the tunica albuginea to the pubic periosteum.20 Some have described penile degloving and reattaching the skin, however these results have not always been successful.20

Complications

Complications after penile curvature repair vary from 5% up to 50% depending on the severity of curvature with an overall rate of 8% and include glans dehiscence, urethrocutaneous fistula, recurrent curvature and erectile dysfunction being the most common,23,12,34

Complications of repair of penile torsion include haematoma, residual penile torsion, reduced parental or patient satisfaction.35

Suggested Follow-Up and Outcomes

Initial postoperative outpatient review can range from six to twelve weeks dependent on the surgeon’s preference. Regarding penile curvature, assessment is via parental and or patient observation of natural erections in addition to physical examination in the outpatient clinic. There are limited studies focussing on appropriate duration of post operative follow-up.23

Congenital Megaprepuce

History

The first published description of buried penis was by Keyes in 1919 where he described the condition arose because the penis lacked its proper ‘sheath of skin’ and remained ‘buried beneath the integument of the abdomen, thigh or scrotum’.36,37 Since 1919, there have been several documented case reports and discussions in this topic with its early contributors laying the platform for the greater work that has been done in the last twenty to thirty years. Campbell in 1951 described “concealed penis” as “a rudimentary organ hidden beneath the skin of the scrotum, perineum, lower abdomen or thigh in the fatty tissues which may be unusually thick”, Glanz in 1968 reported a case in an adult, Warkany in 1971 described a “micropenis or concealed penis”. Williams in 1974 described and illustrated with an example. In 1977, apart from describing his six cases, Crawford proposed the first classification for buried penis.38

Interestingly, two early contributing landmark reports included radiological studies. In 1974 Gwinn and colleagues described in their “radiological case of the month” an 18-month-old boy who had an intravenous urogram done for Hodgkin lymphoma staging. During the voiding phase, they noted that “all of the contrast in his bladder descended into a striking bulbous distention of the prepuce”.

Although not specifically named, their report probably gives the first description of a megaprepuce.39,40 Twenty years later, in 1994, O’Brien et al reported a case of an eleven-month-old boy who was noted to have a “large spheroidal swelling, about the size of an orange” and how his mother “demonstrated how the swelling could be readily deflated by manual compression”. At urethroscopy, they failed to find the meatus because of the redundant prepuce. A suprapubic catheter was placed and a micturating cystogram was performed. Apart from demonstrating a normal bladder and urethra, it was noted that contrast flowed into a large preputial bladder with a capacity as great as his urinary bladder”. They coined the term congenital megaprepuce to describe this which was the first documented use,40,41

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of inconspicuous penis is unknown. However, it has been proposed that this is an emerging condition.42 In a recent literature review, case numbers ranged from 1 to 134 patients, with ages ranging from 2 months to 33 years. On average, surgery was performed before 24 months of age.43

Pathogenesis

Inconspicuous penis may develop as a result of multiple factors rather than a single one. These may include deficiency of penile skin, abnormal attachment of the shaft skin at the base of the penis, penile skin being tethered forward because of dysgenetic dartos and prominent prepubic fat pad. Secondary causes result from complications of cicatricial scarring after circumcision or a large hernia or hydrocele.44

The exact etiology of congenital megaprepuce is not understood but the widely proposed theory is that it results from the tethering effects of abnormal dartos on the shaft of the penis. This is supported by early approaches to the correction of the buried penis, which noted that correction of the defect was successfully achieved by resection of the dartos tissue. A prospective study looking at the histology of dartos noted that almost 80% of patients had abnormal dartos tissue that either had poorly developed smooth muscle fibers or randomly distributed smooth muscle fibers. Interestingly patients with buried penis were more likely to have abnormal dartos compared to the hypospadias group (78% compared to 70%).45 Increased urine volume production after the neonatal period and an abnormal voiding stream due to a narrow preputial opening are what contributes to the ballooning effect of the condition.46

Evaluation and Diagnosis

It is important to distinguish between a normal sized penis that is hidden versus a micropenis. This is the first assessment necessary as the management path is quite different for the two. The former would need ongoing care and most likely operative intervention with the Urologist while the latter would require further evaluation and combined care with the Endocrine and Genetics team. This chapter will not be discussing the management of micropenis.

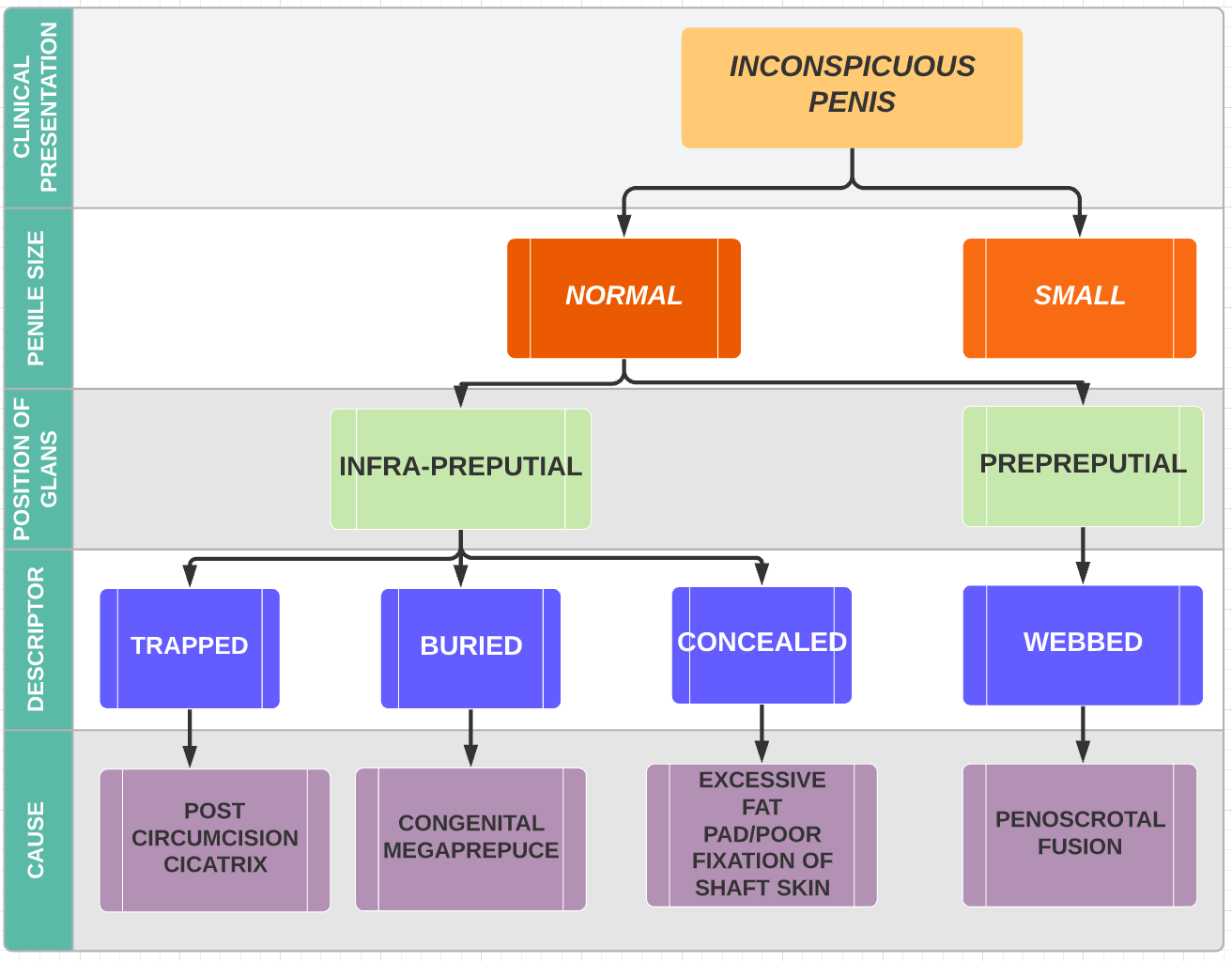

Crawford first classified the buried penis into concealed, buried and penoscrotal web.38 Maizels et al described the different etiologies as: buried, webbed, trapped or micro/ diminutive. This classification has been the most widely used as it encompasses what groups the child may fall into based on clinical examination.47 While describing their surgical approach (Ventral V-plasty) for the correction of the congenital megaprepuce, Alexander and colleagues suggested a classification with more accurate anatomical description and the potential underlying cause (Figure 3), (Figure 4), (Figure 5), (Figure 6), and (Figure 7)3

Figure 3 Classification of the causes of an inconspicuous penis (Alexander et al).

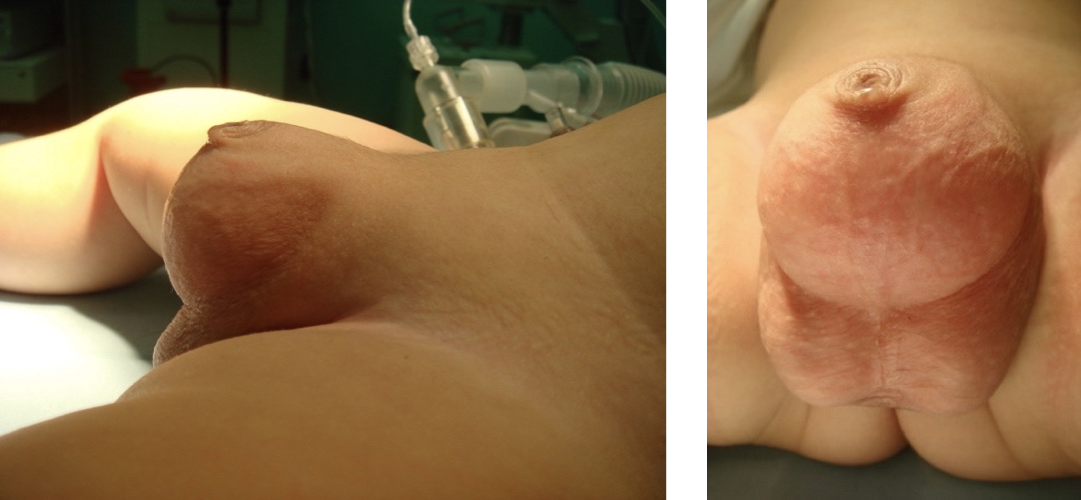

Figure 4 Trapped penis post circumcision

Figure 5 Congenital megaprepuce

Figure 6 Concealed penis

Figure 7 Penoscrotal fusion

Hadidi proposed dividing patients with buried penis into three groups according to their operative findings. Grade 1 – patients with an abnormally long inner prepuce (LIP), Grade 2 – LIP and abnormal distal attachments of the fundiform and suspensory ligaments into the midshaft of the penis, Grade 3 – Grade 1 and 2 plus excess suprapubic fat.37

Treatment Options

Multiple surgical approaches have been described for the exhumation and correction of this group of conditions. The exact timing for surgery has been a contentious issue and essentially influenced by the underlying cause. Advocates for early intervention state reasons that are similar for the timing of hypospadias repair – early intervention (6-12months of age) is advisable to avoid psychological consequences.44,48 Those that are symptomatic (urinary retention, recurrent balanitis, urine tract infections) will benefit from earlier surgery. Other authors recommend surgical correction as soon as the diagnosis is made to resolve both urinary and cosmetic aspects,49,50 On the other hand, correction of a concealed penis resulting from a prominent prepubic fat pad can be delayed as it can improve spontaneously with time, with Donahoe and Keating describing that an adequate skin coverage of the penile shaft was observed with erections.51

There is an array of literature and techniques that describe the correction of congenital megaprepuce.3,42,43,46,52 The main surgical steps are listed below with variations in how each step is performed leading to the diversity of techniques. They can be classified predominantly into either a single (majority of techniques) or a two-stage approach. In the latter a preputioplasty is initially performed with later reassessment of the anatomy after toilet training.

The surgical steps are:

- Removal of the stenotic or phimotic ring

- Unfurling of the prepuce

- Resection or reduction of redundant inner prepuce

- Excising the dysplastic dartos muscle

- Recreation of the peno-pubic and penoscrotal angle by attaching shaft dermis to Buck’s fascia at 4 and 8 o’clock

- Penile shaft coverage–most techniques differ in the tissue used to cover the penile shaft. This can be achieved by utilising penile skin, the redundant inner prepuce or a combination of the two.

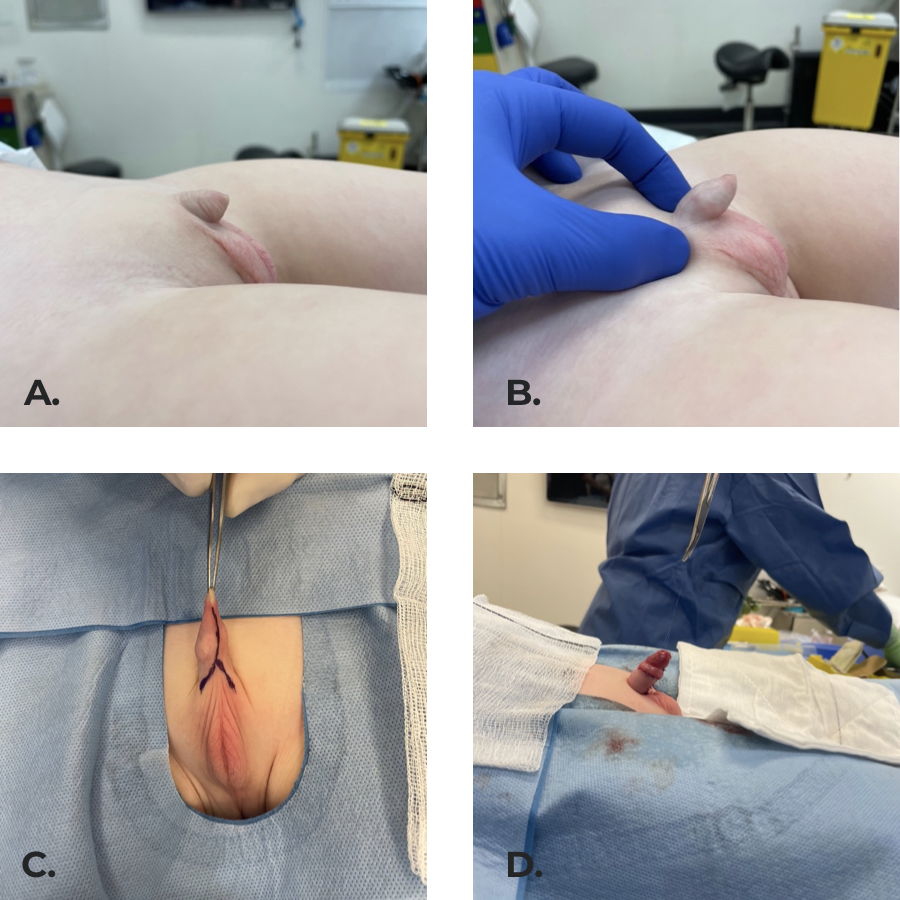

It is our preference to use the anatomical approach as we have had good outcomes in our experience (Figure 8),52,53

Figure 8 Inconspicuous penis secondary to penoscrotal fusion and poorly defined peno-pubic angle. (b) penis exposed on examination. (c) Surgical incisions marked. (d) Final result with the penile shaft covered by skin, pubic and scrotal angles created by securing dermis to Buck’s fascia at 4 and 8 o’clock.

Figure 8 Inconspicuous penis secondary to penoscrotal fusion and poorly defined peno-pubic angle. (b) penis exposed on examination. (c) Surgical incisions marked. (d) Final result with the penile shaft covered by skin, pubic and scrotal angles created by securing dermis to Buck’s fascia at 4 and 8 o’clock.

Complications

Short term postoperative complications are hematoma, wound dehiscence and penile / scrotal oedema. Medium to long term complications include the need for redo surgery due to lymphoedema leading to excessive inner preputial skin, meatal stenosis and retraction of the penis,3,42,46,52,54

Suggested Follow-Up and Outcomes

Given that some of the complications have been reported later in life, long term follow up for these patients is recommended. Shalaby and Cascio reported a median follow up of 17 to 61 months.40

Conclusions

Congenital penile conditions are uncommon, therefore, referral to a pediatric urologist for a correct diagnosis and management is recommended.

Key Points

- Surgical correction is recommended for congenital penile curvature greater than 20 degrees

- A step-wise approach with protection of neurovascular structures and preservation of urethral plate is preferred when repairing penile curvature (without hypospadias)

- Consider correction of penile torsion greater than 45 degrees

- Excision of the dysplastic dartos and skin fixation to Buck’s fascia are key steps when correcting a congenital megaprepuce

- Limit skin excision until adequate coverage of the penile shaft is ensured

- Initial nonoperative management is preferred for the concealed penis

Suggested Readings

- Mingin G, Baskin LS. Management of chordee in children and young adults. Urol Clin North Am 2002; 29 (2): 277–284, DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00044-7.

- Smeulders N, Wilcox DT, Cuckow PM. The buried penis-an anatomical approach. BJU Int 2000; 86 (4): 523–526, DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00752.x.

- Alexander A, Lorenzo AJ, Salle JLP, Rode H. The Ventral V-plasty: a simple procedure for the reconstruction of a congenital megaprepuce. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45 (8): 1741–1747, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.03.033.

- Shalaby M, Cascio S. Megaprepuce: a systematic review of a rare condition with a controversial surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int 2021; 37 (6): 815–825, DOI: 10.1007/s00383-021-04883-5.

References

- Snodgrass WT. Management of penile curvature in children. Curr Opin Urol 2008; 18 (4): 431–435, DOI: 10.1097/mou.0b013e32830056d0.

- Slawin KM, Nagler HM. Treatment of congenital penile curvature with penile torsion: a new twist. J Urol 1992; 147 (1): 152–154, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37169-0.

- Alexander A, Lorenzo AJ, Salle JLP, Rode H. The Ventral V-plasty: a simple procedure for the reconstruction of a congenital megaprepuce. J Pediatr Surg 2010; 45 (8): 1741–1747, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2010.03.033.

- Gredler ML. Evolution of external genitalia: insights from reptilian development. Sex Dev 2014; 8 (5): 311–326, DOI: 10.1159/000365771.

- Yiee JH, Baskin LS. Penile embryology and anatomy. ScientificWorldJournal 2010; 10: 1174–1179, DOI: 10.1100/tsw.2010.112.

- Baskin L. Development of the human penis and clitoris. Differentiation 2018; 103: 74–85, DOI: 10.1016/j.diff.2018.08.001.

- Kaplan GW, Lamm DL. Embryogenesis of chordee. J Urol 1975; 114 (5): 769–772, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)67140-4.

- Bellinger MF. Embryology of the Male External Genitalia. Urologic Clinics of North America 1981; 8 (3): 375–382, DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(21)01293-3.

- Nesbit RM. CONGENITAL CURVATURE OF THE PHALLUS: REPORT OF THREE CASES WITH DESCRIPTION OF CORRECTIVE OPERATION. J Urol 1965; 93: 230–232, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)63751-0.

- Fevre. Treatment of bends and twists of the penis. Sem Hop 1947; 23 (14): 895,.

- Azmy A, Eckstein HB. Surgical correction of torsion of the penis. Br J Urol 1981; 53 (4): 378–379, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1981.tb03202.x.

- Donnahoo KK. Etiology, management and surgical complications of congenital chordee without hypospadias. J Urol 1998; 160 (3 Pt 2): 1120–1122, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)62713-7.

- Kramer SA, Aydin G, Kelalis PP. Chordee without hypospadias in children. J Urol 1982; 128 (3): 559–561, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80141-9.

- Kelâmi A. Classification of Congenital and Acquired Penile Deviation. Urologia Internationalis 1983; 38 (4): 229–233, DOI: 10.1159/000280897.

- Sarkis PE, Sadasivam M. Incidence and predictive factors of isolated neonatal penile glanular torsion. J Pediatr Urol 2007; 3 (6): 495–499, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.03.002.

- Ben-Ari J, Merlob P, Mimouni F, Reisner SH. Characteristics of the male genitalia in the newborn: penis. J Urol 1985; 134 (3): 521–522, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47272-7.

- Devine CJ Jr, Horton CE. Chordee without hypospadias. J Urol 1973; 110 (2): 264–271, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)60183-6.

- Snodgrass W, Patterson K, Plaire JC, Grady R, Mitchell ME. Histology of the urethral plate: implications for hypospadias repair. J Urol 2000; 164 (3 Pt 2): 988–989 989–990, DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00017.

- Montag S, Palmer LS. Abnormalities of penile curvature: chordee and penile torsion. ScientificWorldJournal 2011; 11: 1470–1478, DOI: 10.1100/tsw.2011.136.

- Zhou L, Mei H, Hwang AH, Xie H-W, Hardy BE. Penile torsion repair by suturing tunica albuginea to the pubic periosteum. J Pediatr Surg 2006; 41 (1): 7–9, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.065.

- Mingin G, Baskin LS. Management of chordee in children and young adults. Urol Clin North Am 2002; 29 (2): 277–284, DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00044-7.

- Bologna RA, Noah TA, Nasrallah PF, McMahon DR. Chordee: varied opinions and treatments as documented in a survey of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Section of Urology. Urology 1999; 53 (3): 608–612, DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00656-6.

- Tang Y-M, Chen S-J, Huang L-G, Wang M-H. Chordee without hypospadias: report of 79 Chinese prepubertal patients. J Androl 2007; 28 (4): 630–633, DOI: 10.2164/jandrol.106.002436.

- Baskin LS, Erol A, Li YW, Cunha GR. Anatomical studies of hypospadias. J Urol 1998; 160 (3 Pt 2): 1108–1115. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)62711-3.

- Mollard P, Castagnola C. Hypospadias: the release of chordee without dividing the urethral plate and onlay island flap (92 cases. J Urol 1994; 152 (4): 1238–1240, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32557-0.

- Bhat A. Extended urethral mobilization in incised plate urethroplasty for severe hypospadias: a variation in technique to improve chordee correction. J Urol 2007; 178 (3 Pt 1): 1031–1035, DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.074.

- Koff SA, Eakins M. The treatment of penile chordee using corporeal rotation. J Urol 1984; 131 (5): 931–932, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)50716-8.

- Perovic SV, Djordjevic ML. A new approach in hypospadias repair. World J Urol 1998; 16 (3): 195–199, DOI: 10.1007/s003450050052.

- Ballesteros N. Use of small intestinal submucosa for corporal body grafting in cases of epispadias and epispadias/exstrophy complex. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (4): 406 1–406 6, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.024.

- Castellan M, Gosalbez R, Devendra J, Bar-Yosef Y, Labbie A. Ventral corporal body grafting for correcting severe penile curvature associated with single or two-stage hypospadias repair. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (3): 289–293, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.03.008.

- Shaeer O, Shaeer K. Shaeer’s Corporal Rotation III: Shortening-Free Correction of Congenital Penile Curvature-The Noncorporotomy Technique. Eur Urol 2016; 69 (1): 129–134, DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2015.08.004.

- Bhat A, Bhat MP, Saxena G. Correction of penile torsion by mobilization of urethral plate and urethra. J Pediatr Urol 2009; 5 (6): 451–457, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2009.05.013.

- Fisher PC, Park JM. Penile torsion repair using dorsal dartos flap rotation. J Urol 2004; 171 (5): 1903–1904, DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000120148.79867.5c.

- Badawy H, Morsi H. Long-term followup of dermal grafts for repair of severe penile curvature. J Urol 2008; 180 (4 Suppl): 1842–1845, DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.082.

- Bar-Yosef Y, Binyamini J, Matzkin H, Ben-Chaim J. Degloving and realignment-simple repair of isolated penile torsion. Urology 2007; 69 (2): 369–371, DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.01.014.

- Keyes EL, Others. Phimosis, paraphimosis, tumors of the penis. Urology 1919; 67: 649,.

- Hadidi AT. Buried penis: classification surgical approach. J Pediatr Surg 2014; 49 (2): 374–379, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.09.066.

- Crawford BS. Buried penis. Br J Plast Surg 1977; 30 (1): 96–99, DOI: 10.1016/s0007-1226(77)90046-7.

- Gwinn JL, Lee FA, Haber K. Radiological case of the month. Unusual presentation of phimosis. Am J Dis Child 1974; 128 (6): 835–836,.

- Shalaby M, Cascio S. Megaprepuce: a systematic review of a rare condition with a controversial surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int 2021; 37 (6): 815–825, DOI: 10.1007/s00383-021-04883-5.

- O’Brien A, Shapiro AM, Frank JD. Phimosis or congenital megaprepuce? Br J Urol 1994; 73 (6): 719–720, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1995.tb07856.x.

- Summerton DJ, McNally J, Denny AJ, Malone PS. Congenital megaprepuce: an emerging condition-how to recognize and treat it. BJU Int 2000; 86 (4): 519–522, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2001.0003c.x.

- Werner Z, Hajiran A, Al-Omar O. Congenital Megaprepuce: Literature Review and Surgical Correction. .

- Park NC, Kim SW, Moon DG. Penile Augmentation. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2016, DOI: 10.1007/978-3-662-46753-4.

- Spinoit A-F, Praet C, Groen L-A, Laecke E, Praet M, Hoebeke P. Congenital penile pathology is associated with abnormal development of the dartos muscle: a prospective study of primary penile surgery at a tertiary referral center. J Urol 2015; 193 (5): 1620–1624, DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2014.10.090.

- Ruiz E. Simplified surgical approach to congenital megaprepuce: fixing, unfurling and tailoring revisited. J Urol 2011; 185 (6 Suppl): 2487–2490, DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.015.

- Maizels M, Zaontz M, Donovan J, Bushnick PN, Firlit CF. Surgical correction of the buried penis: description of a classification system and a technique to correct the disorder. J Urol 1986; 136 (1 Pt 2): 268–271, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)44837-3.

- Shapiro SR. Surgical treatment of the ’buried’ penis. Urology 1987; 30 (6): 554–559, DOI: 10.1016/0090-4295(87)90435-3.

- Ferro F, Spagnoli A, Spyridakis I, Atzori P, Martini L, Borsellino A. Surgical approach to the congenital megaprepuce. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2006; 59 (12): 1453–1457, DOI: 10.1016/j.bjps.2005.12.033.

- Philip I, Nicholas JL. Congenital giant prepucial sac: case reports. J Pediatr Surg 1999; 34 (3): 507–508, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(99)90515-8.

- Donahoe PK, Keating MA. Preputial unfurling to correct the buried penis. J Pediatr Surg 1986; 21 (12): 1055–1057, DOI: 10.1016/0022-3468(86)90007-2.

- Betancor CEL, Cherian A, Smeulders N, Mushtaq I, Cuckow P. Mid- to long-term outcomes of the ’anatomical approach’ to congenital megaprepuce repair. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (3): 243 1–243 6, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.02.007.

- Hirsch K, Schwaiger B, Kraske S, Wullich B. Megaprepuce: presentation of a modified surgical technique with excellent cosmetic and functional results. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (4): 401 1–401 6, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.018.

- Rod J, Desmonts A, Petit T, Ravasse P. Congenital megaprepuce: a 12-year experience (52 cases) of this specific form of buried penis. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (6 Pt A): 784–788, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.10.010.

- Callewaert PRH, Rahnama’i MS, Guimarães MNC, Vrijens DMJ, Kerrebroeck PEVA. DOuble LOngitudinal Megapreputium Incision TEchnique: the DOLOMITE. Urology 2014; 83 (5): 1149–1154, DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.12.014.

- Lin H-W. An arc incision surgical approach in congenital megaprepuce. Chin Med J 2015; 128 (4): 555–557, DOI: 10.4103/0366-6999.151117.

- Smeulders N, Wilcox DT, Cuckow PM. The buried penis-an anatomical approach. BJU Int 2000; 86 (4): 523–526, DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00752.x.

Última actualización: 2023-02-22 15:40