26: Congenital and Traumatic Urethral Stricture

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 13 minutos para leer.

Introduction

Urethral strictures were initially thought to be uncommon in children.1 Later reports suggested that they are not so rare.2 The impression of low incidence was mainly due to under-reporting and sparse literature. Johanson was the first to observe the stricture formation in 1953 after complete urethral disruption.1 Urethral strictures are broadly classified based on their etiology into congenital/idiopathic, iatrogenic, inflammatory, and traumatic. It is unclear whether strictures with no definite cause should be classified into congenital or idiopathic.

Harshman et al and Kaplan & Brock recommended to avoid the designation of congenital urethral stricture and described such lesions as strictures of unknown etiology.3,4 It is unclear whether catheter-induced strictures can be classified as iatrogenic or inflammatory. Since such a stricture would not have occurred without an indwelling catheter in the first place, one may argue that it should be classified as iatrogenic.2 Iatrogenic causes like catheterization or post hypospadias repair stricture account for the majority of anterior urethral stricture disease in the pediatric population, especially the younger age-group. However, as the child grows, there is a gradual preponderance of traumatic urethral strictures, including posterior urethral strictures.

Congenital and Idiopathic Strictures

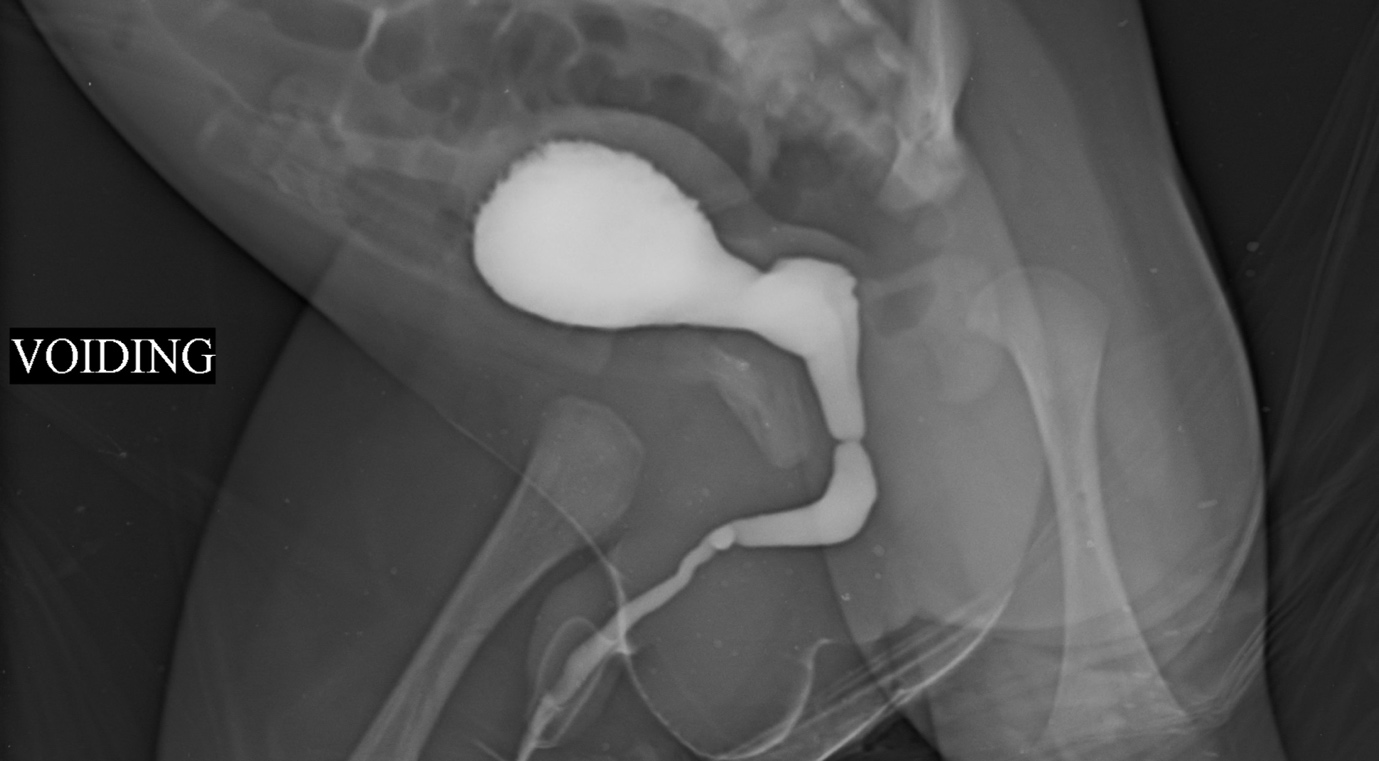

Mori et al reported that congenital urethral stenosis/stricture was an important cause of recurrent urinary tract infections, enuresis, frequency or hematuria in in boys.5 It is recognized as a typical straight line filling (Figure 1) Also referred to as Cobb’s collar or Moorman’s ring or congenital obstructing posterior urethral membrane (COPUM), their etiology is obscure. It is debated whether this entity could be referred to as a stricture.

Figure 1 VCUG showing idiopathic/ congenital urethral stricture/ stenosis. Ring like narrowing is seen at the junction of anterior and posterior urethra. Often the upper tracts are not dilated and they present with UTI or dribbling

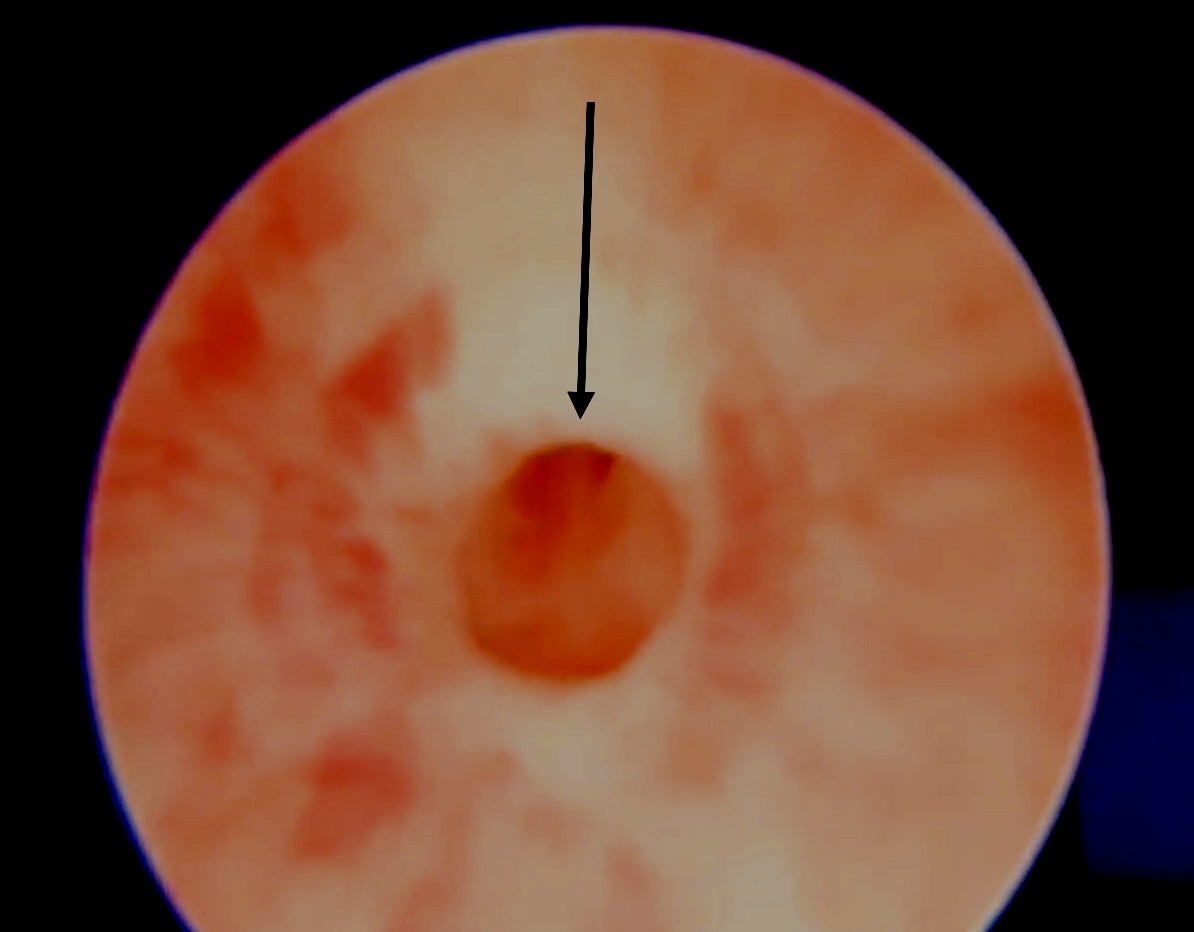

This lesion is noticed as a ring-form of stenosis on cystoscopy (Figure 2) just distal to the external urethral sphincter.6 Typically the features like bladder irregularity, thickening or upper tract changes seen in posterior urethral valves (PUV) are absent. The most effective treatment of this lesion is optic internal urethrotomy (OIU) under direct vision. This is performed at 12 O’ clock position using a cold knife (arrow of (Figure 2) In boys with daytime wetting and a congenital bulbar urethral stenosis, wetting episodes improved in 69.4% after OIU.5 Furthermore, urinary tract infections and vesicoureteral reflux reduced by prompt treatment of this pathology.

Figure 2 Optical internal urethrotomy (OIU) for idiopathic/ congenital narrowing involves cold knife division at 12 O’clock position

Iatrogenic Strictures

Catheter Induced Strictures

Urethral catheterization is an important iatrogenic cause (12.3% overall), and is the main cause of multifocal and pan anterior urethral stricture in a study by Ansari et al.2 Iatrogenic strictures due to prolonged catheterisation (often inserted for output monitoring in neuro ICUs) are often located at bulbo membranous region. While some of them may be due to oversized catheters, some may be due to inflation of bulb in urethra or traumatic catheter removal (often urethral bleeding is noted in such a situation). Prolonged catheterisation itself causes urethral inflammation, ischemia and ultimately urethral stricture. Often they present with retention following catheter removal. In such a situation the author prefers to perform a supra pubic catheter (SPC) insertion under ultrasound guidance. This helps in future trial voiding by clamping the SPC. Also the SPC may be used for a voiding cysto urethrogram (VCUG) to assess the extent of stricture. Often these strictures are short segment narrowing amenable to OIU under general anaesthesia. Following OIU, a repeat VCUG and trial voiding are needed to ensure resolution of stricture. Clear and well defined indications for catheterization, skilled urethral catheter insertion, and consideration of SPC when prolonged catheterization is likely should decrease the incidence of these iatrogenic strictures.

Strictures Following Posterior Urethral Valve

Transurethral valve fulguration is another important cause of pediatric stricture urethra. Although specific data on contribution of valve fulguration to pediatric strictures are lacking, the incidence ranges from 0% to 25% in various series.7 In a latest series, 11 of 62 patients (5.6% of overall) had an iatrogenic stricture after valve fulguration.2 While various causes have been proposed in the development of these strictures, the most important is traumatic insertion of an oversized resectoscope in a narrow urethral lumen and monopolar current leakage due to insufficient insulation of the resectoscope or overzealous buzzing. It is felt that this is an avoidable cause of strictures in kids, which can be prevented by gentleness in surgical technique, using appropriate-sized small instruments for fulguration in a narrow infant urethra, decreasing the contact time during fulguration to avoid deep cuts and fulguration under direct vision only at the area of valves.8 The authors prefer to use cold knife ablation over diathermy fulgration for PUV ablation to prevent thermal injury and reduce stricture formation.9 Often strictures following valve ablation are narrow segment strictures amenable to OIU. This has to be performed carefully with an upfront guide wire insertion.

Hypospadias Strictures

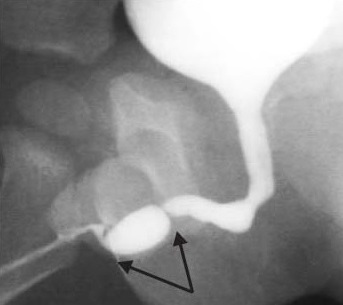

Strictures following hypospadias repair account for a good proportion of anterior urethral strictures in adolescents and young adults. They may present early with poor stream and dribbling or late with recurrent urinary tract infections (UTI) and upper tract changes. Their presentation is highly variable, and they may be diagnosed late, especially in the early adulthood after a supposedly ‘successful’ repair in childhood with no fistulas. Ansari emphasized the need to warn parents that children undergoing hypospadias repair could develop strictures in the future and should be monitored during adolescence for stricture formation.2 Often the uroflow shows a flat trace with a large post void residual urine. Hypospadias strictures following distal urethral repair (tubularised incised plate- TIP) are often long segment stenosis due to poor urethral lumen. These present early with straining and dribbling. They often need to be laid open until normal calibre urethra is reached. They may need local prepucial skin graft/ oral mucosa graft (OMG) or buccal mucosa graft (BMG) as an inlay while being laid open. After a period of 6 months, these can be tubularised to provide a wider calibre urethra. Hypospadias stricture following proximal urethra repair (after a single stage tubularised repair – Duckett) often are due to narrowing at the junction of native urethra and skin lined neourethra. An ascending urethrogram (AUG) is needed to demonstrate the exact location and extent of narrowing (Figure 3) If a narrow ring stricture is found at the junction of neo urethra with native urethra, an OIU alone may suffice. On the other hand a dense long segment stricture may need OMG/BMG staged repair.10 (Figure 4) depicts a flow chart in the management of hypospadias anterior urethral strictures (HAUS). The entire narrow scarred segment is excised and OMG is quilted in place. Following a period of 6 months to 1 year, tubularisation is performed. Barbagli reported that stricture length, but not the number of previous operations needed for primary hypospadias repair, was associated with the risk of failure.11 Some surgeons favour a single stage dorsal OMG inlay repair for these situations while the author favours a two staged approach.12,13

Figure 3 Anterior urethral stricture following hypospadias repair often noticed at the junction of native urethra and neo urethra. Multiple fold like narrowing are amenable to OIU while long anterior urethral strictures need oral mucosa grafting with two stage repair.

Figure 4 A flow chart in the management of hypospadias anterior urethral strictures (HAUS).

Inflammatory Strictures

Unlike adult series, strictures due to lichen sclerosis (LS) or infectious causes are rare in children.14 Although LS is often thought to be a disease of adulthood, balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) akin to LS is an important cause of urethral strictures especially in older children. Recent reports show they are not so uncommon as thought before.15 These strictures are more difficult to treat and need multiple interventions as they are a chronic inflammatory process and have a tendency to recur.2 Pediatric urologists operating these strictures should explain to the caregivers about the condition and the need for prolonged follow-up to identify recurrences.

Buccal and Oral Mucosa Graft Substitution Urethroplasty

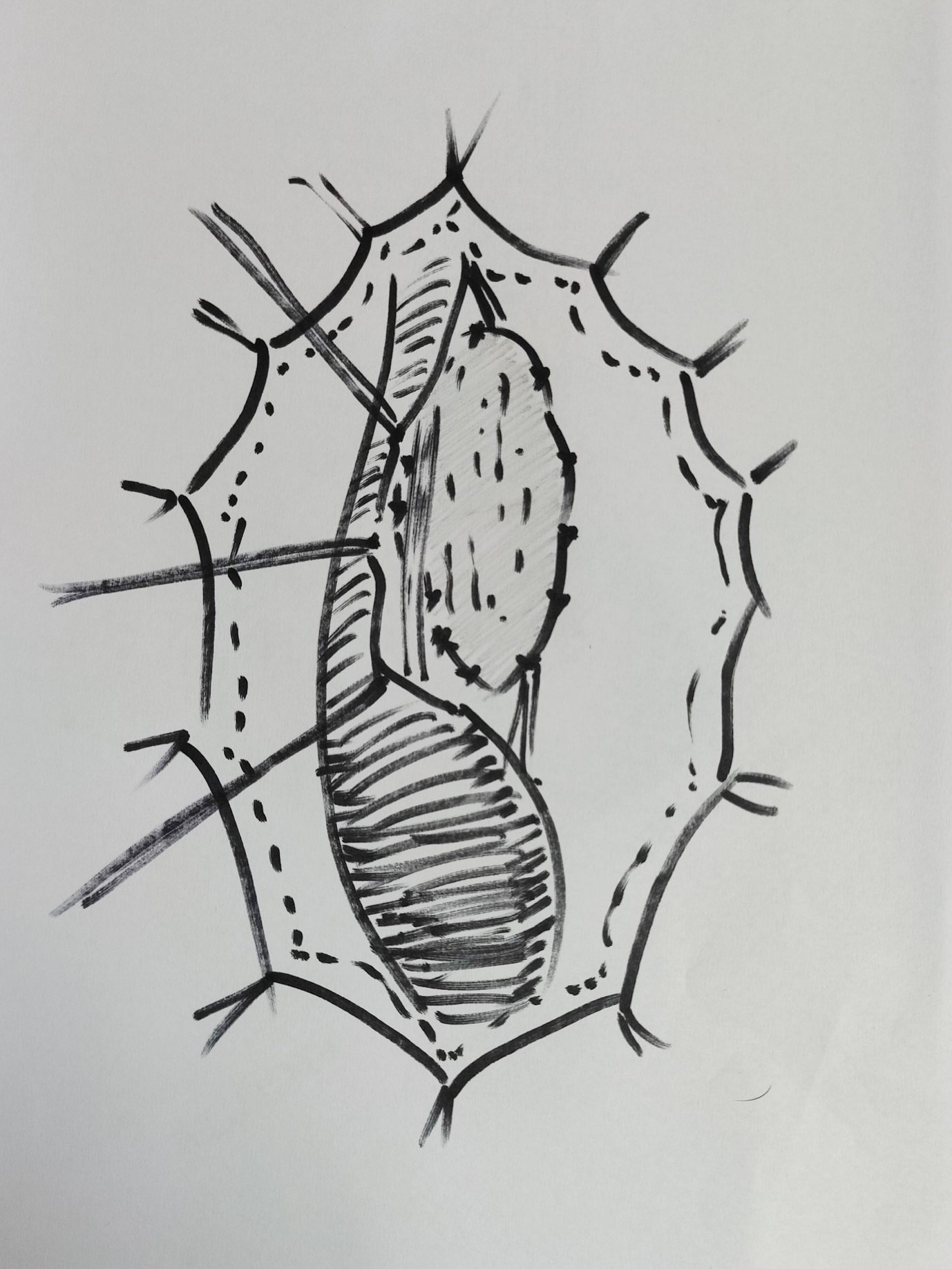

Anterior urethral strictures not amenable to end-to-end anastomosis, require substitution urethroplasty. This can be achieved by using penile skin flaps or free grafts of full-thickness skin, bladder oral mucosa (OMG) or buccal mucosa (BMG). OMG/ BMG substitution urethroplasty is fast emerging as the most preferable technique for pan urethral strictures involving distal urethra.16 In those with pendulous urethral strictures a circum-coronal incision is used, while for more proximal strictures a midline perineal incision is used. The spongiosum is then detached dorsally from the corpora and a urethrotomy is made at 12 o'clock position. In patients with inflammatory or traumatic strictures this approach is easier while in those with hypospadias stricture spongiosum is typically scarred/ absent making only ventray lay opening at 6 o’clock position feasible. In such cases a two-stage procedure involves complete excision of the fibrotic tissue and BMG quilting in the first stage. The urethra is reconstructed in the second stage, 4–6 months after the first.

In a single stage dorsal onlay repair, for inflammatory or traumatic strictures, BMG/OMG is quilted to the corpora with interrupted 6–0 polyglactin sutures, and subsequently sutured to the cut edges of the urethra with continuous sutures. Barbagli et al have described the detailed operative steps (Figure 5)17 For meatal reconstruction, the distal most BMG is fixed with interrupted 5–0 polyglactin sutures to the dorsally cut margins of the meatus. The patient is discharged 3–5 days after surgery with an indwelling urethral and a suprapubic catheter. Catheters are removed 3 weeks later, after a voiding cystourethrography. While some authors favour the dorsal onlay technique others have reported excellent long-term outcomes with ventral onlay techniques,5,18,19

Figure 5 BMG dorsal onlay substitution urethroplasty; urethra has been mobilised; opened at 12 0’clock position dorsally; BMG quilted dorsally and being anastomosed to edges.

Traumatic Strictures

Traumatic etiology becomes a major contributor to stricture disease as the age advances. In a series by Ansari, 36.9% of the overall strictures were due to traumatic etiology.2 While 18% of strictures in children younger than 10 years were secondary to trauma, 45% of the strictures in patients older than 10 years were traumatic in origin. Pelvic fracture an important cause of stricture urethra in adolescents is usually after a fall from height or road traffic accidents or perineal trauma due to straddle injury.

Turner Warwick introduced the term “complex” pelvic fracture posterior urethral distraction defect (PFPUDD) when one or more of the following features are present: (a) the length of the distraction defect is long (≥3 cm) surrounded by extensive pelvic fibrosis and (b) are accompanied by para-urethral diverticulae, false passages, or simultaneous bladder neck lesion.20 Most of the complex urethral distraction defects require a wider surgical exposure to restore urethral continuity.21

Although pathogenesis of PFPUDD in children tends to follow a similar pattern to the one in adults, several key elements require consideration. Location of traumatic urethral injury in children is often unpredictable due to the abdominal position of the bladder and immaturity of the prostate.22 Some other factors to be considered in children are: (a) urethral distraction defects tend to be longer than in adults because of marked upwards displacement of the bladder and prostate, (b) double injuries at the bladder neck and the membranous urethra are more frequently observed in children and (c) pre-pubertal size of the perineum may make it difficult to reach a high lying proximal urethral end.23

Colapinto and McCallum24 classified traumatic posterior urethral injuries into three categories based on the radiological appearance. In type 1 the prostate or urogenital diaphragm is dislocated but the membranous urethra is merely stretched and not severed. In type 2 the membranous urethra is ruptured above the urogenital diaphragm at the apex of the prostate. In type 3 the membranous urethra is ruptured above and below the urogenital diaphragm Recently, a new classification of posterior urethral injury in patients with fractured pelvis was proposed.25 The new classification scheme allows us to compare different therapeutic strategies and their outcomes (Table 1)

Table 1 Unified anatomical and mechanical classification of traumatic urethral strictures.

| Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| I | The posterior urethra stretched but intact |

| II | Tear of the prostatomembranous urethra above the urogenital diaphragm |

| III | Partial or complete tear of both anterior urethra and posterior urethra with disruption of the urogenital diaphraqm |

| IV | Bladder injury extending into the urethra |

| IVa | Injury of the bladder base with periurethral extravasation simulating posterior urethral injury |

| V | Partial or complete pure anterior urethral injury |

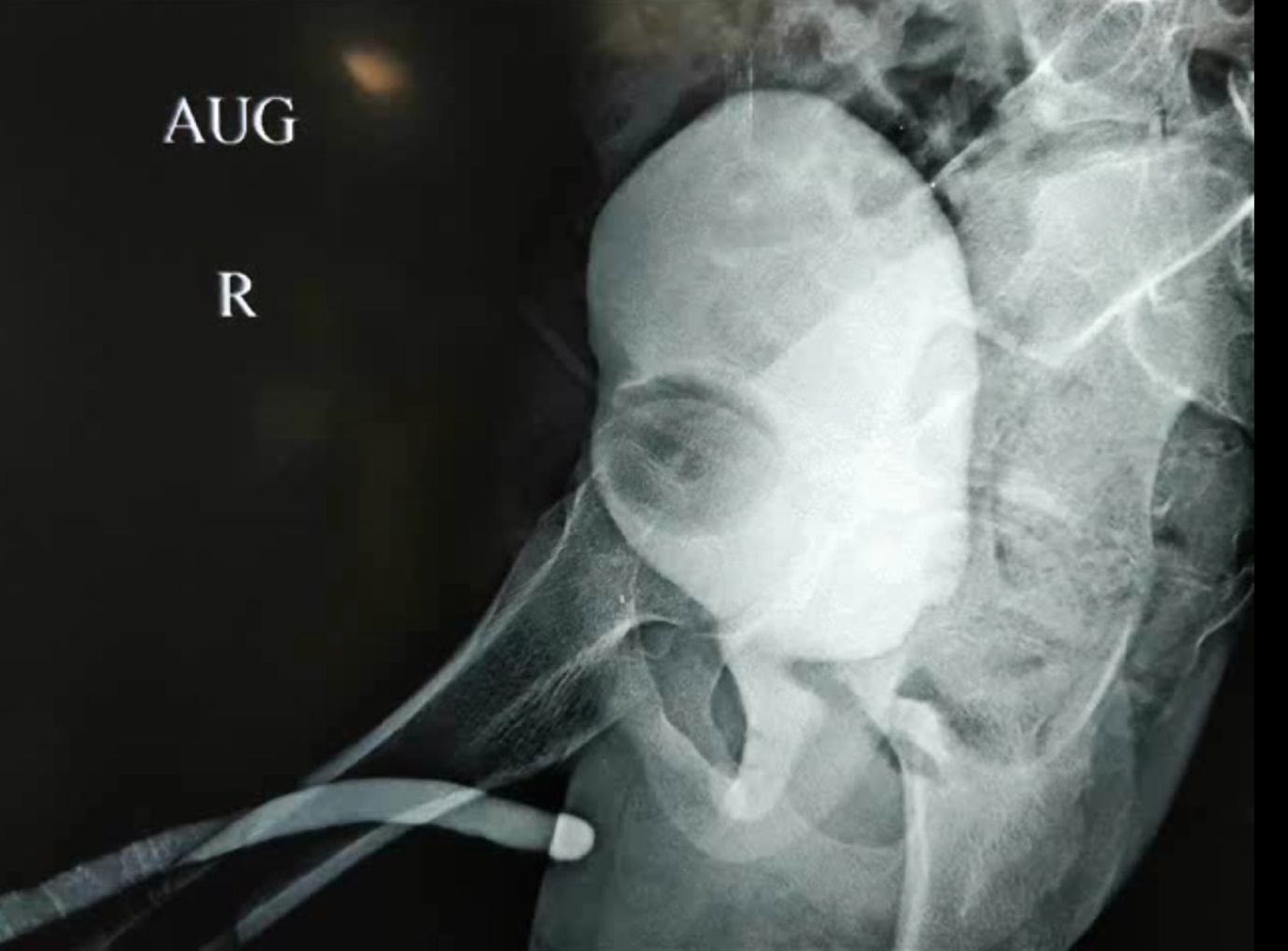

Debate is still present among pediatric urologists on the superior approach: early urethral realignment with or without primary reconstruction of the transected urethra vs. primary SPC and deferred repair of the urethra. Nerli et al.26 reported that half of the children undergoing primary realignment needed additional endoscopic urethrotomies, while some required urethroplasty to manage a resultant stricture. The author favours primary SPC to tide over the acute phase of retention following trauma. We also prefer to avoid urethral instrumentation which may further urethral damage or a risky pelvic exploration that can disturb a hematoma and prevent a proper approximation. After a period of 6-8 months when orthopaedic stabilisation is removed, an opposing urethrogram is performed to assess the location and length of the stricture (Figure 6) Several surgical procedures have been proposed for the delayed repair of PFPUDDs. These include urethral dilatation, endoscopic techniques like OIU, substitution procedures and deferred tension-free anastomotic repair.

Figure 6 Opposing urethrogram is an essential step in assessing the extent of post traumatic urethral distraction defects. It is typically performed by injecting contrast from SPC to fill posterior urethra while injecting via meatus to fill anterior urethra.

OIU can be advantageous for both the management of annular membranous strictures following partial urethral injuries or for short non-obliterative strictures after failed post-traumatic primary anastomotic repair.27 The current understanding is urethral dilatation and OIU for PFPUDD are not acceptable in children; as the reported results have been poor, and patients undergoing these procedures often need additional surgical operations.23,28

Anastomotic Urethroplasty

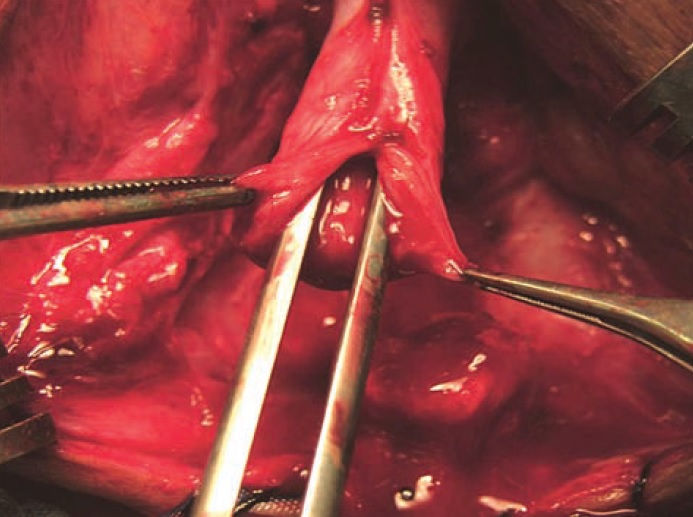

Anastomotic urethroplasty is currently favoured approach for restoration of urethral continuity in children and adults with PFPUDDs. Success of anastomotic urethroplasty is often dependent on adequate surgical exposure, excision of all fibrous tissue occupying the distraction defect, mobilization of the normal bulbar urethra, fixation of healthy mucosa at the edges of the bulbar and prostatic urethral ends and performing a tension-free spatulated anastomosis (Figure 7), (Figure 8), when appropriate blood supply is present through the urethra. Anastomotic repair can be attempted by many approaches: (a) perineal approach, (b) elaborated 1-stage perineal access, (c) transpubic (partial or total) approach, (d) progressive perineal-abdominal (transpubic) approach, and (e) posterior sagittal access.

Figure 7 Proper mobilisation of bulbar urethra and wide anastomosis after spatulation are crucial steps

Figure 8 Mobilisation of crura and chipping away of inferior pubic ramus help in shorter route and better alignment

Perineo-abdominal (transpubic) approach enables progression from a perineal to a perineal-abdominal access with or without partial pubectomy, according to the intra operative anatomical features of the urethral distraction defect and allows supracrural re-routing of the mobilized urethra if needed. The elaborated 1-stage perineal access provides stepwise maneuvers to accomplish a tension-free anastomosis: (a) adequate mobilization of the bulbar urethra, (b) separation of the proximal corporeal bodies, (c) resection of the inferior margin of the pubic arch, and (d) the possibility to reroute the anterior urethra around one corporeal body to shorten the course of the mobilized urethra

An overall success rate of 75-85% is reported for anastomotic urethroplasty.29 Failed perineal urethroplasty was attributed to improper patient selection - a distraction defects of at least 3 cm of length with significant cephalic displacement of the prostate. In children with PFPUDD, surgical repair should begin through a perineum exposure and when tension–free anastomosis is not possible an abdominal (partial pubectomy) approach is required for the correction of the distraction defect.21

Conclusions

Iatrogenic causes (catheterization, PUV, hypospadias repair) account for the majority of anterior urethral strictures in the younger age-group; while as the child grows, traumatic and posterior urethral strictures take preponderance. Initial treatment of traumatic posterior urethral injuries associated with pelvic fractures should aim at stabilizing the patient, SPC and treating the life-threatening associated injuries. Preoperative evaluation of the established urethral distraction defect includes opposing urethrogram and cystoscopy to define the anatomical extent of the urethral distraction defect. When a healthy anterior urethra is present anastomotic urethroplasty is ideal to treat PFPUDDs. BMG/OMG inlay substitution urethroplasty are mainly indicated for pan urethral strictures.

References

- Herle K, Jehangir S, Thomas RJ. Stricture Urethra in Children: An Indian Perspective. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2018; 23 (4): 192–197, DOI: 10.4103/jiaps.JIAPS_146_17.

- Ansari MS, Yadav P, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Shekar PA. Etiology and characteristics of pediatric urethral strictures in a developing country in the 21st century. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (4): 403 1–403 8, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2019.05.020.

- Harshman MW, Cromie WJ, Wein AJ, Duckett JW. Urethral Stricture Disease in Children. J Urol 1981; 126 (5): 650–654, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)54675-3.

- Kaplan GW, Brock WA. Urethral Strictures in Children. J Urol 1983; 129 (6): 1200–1203, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)52641-5.

- Mori Y. Treatment of congenital urethral stenosis (urethral ring) in children. Optic internal urethrotomy in the congenital bulbar urethral stenosis in boys. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1989; 80 (5): 704–710, DOI: 10.5980/jpnjurol1989.80.704.

- Gobbi D, Leon FF, Gnech M, Midrio P, Gamba P, Castagnetti M. Management of Congenital Urethral Strictures In Infants. Case Series. Urol J 2019; 16 (1): 67–71, DOI: 10.22037/uj.v0i0.4045.

- Lal R, Bhatnagar V, Mitra DK. Urethral strictures after fulguration of posterior urethral valves. J Pediatr Surg 1998; 33 (3): 518–519, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90102-6.

- Myers DA, Walker RD. Prevention of Urethral Strictures in the Management of Posterior Urethral Valves. J Urol 1981; 126 (5): 655–656, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)54676-5.

- Babu R, Kumar R. Early outcome following diathermy versus cold knife ablation of posterior urethral valves. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (1). DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.02.014.

- Payne CE, Sumfest JM, Deshon GEJ. Buccal mucosal graft for hypospadias repairs. Tech Urol 1998; 4 (4): 173–176.

- Barbagli G. Correlation Between Primary Hypospadias Repair and Subsequent Urethral Strictures in a Series of 408 Adult Patients. Eur Urol Focus 2017; 3 (2–3): 287–292, DOI: 10.1016/j.euf.2017.02.005.

- Ye W-J, Ping P, Liu Y-D, Li Z, Huang Y-R. Single stage dorsal inlay buccal mucosal graft with tubularized incised urethral plate technique for hypospadias reoperations. Asian J Androl 2008; 10 (4): 682–686, DOI: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2008.00398.x.

- Schwentner C. Interim outcome of the single stage dorsal inlay skin graft for complex hypospadias reoperations. J Urol 2006; 175 (5): 1872–1877, DOI: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)01016-5.

- Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Verze P, Nunzio C, Vitarelli A, Carmignani L. Contemporary urethral stricture characteristics in the developed world. Urology 2013; 81 (1): 191–196, DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.062.

- Celis S. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and adolescents: A literature review and clinical series. J Pediatr Urol 2014; 10 (1): 34–39, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.09.027.

- Dubey D, Kumar A, Mandhani A, Srivastava A, Kapoor R, Bhandari M. Buccal mucosal urethroplasty: a versatile technique for all urethral segments. BJU Int 2005; 95 (4): 625–629, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05352.x.

- Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Kulkarni SB, Romano G, Lazzeri M. Dorsal onlay oral mucosal graft bulbar urethroplasty. BJU Int 2012; 109 (11): 1728–1741, DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11006.x.

- Dubey D. Substitution urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures: a critical appraisal of various techniques. BJU Int 2003; 91 (3): 215–218, DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.03064.x.

- Heinke T, Gerharz EW, Bonfig R, Riedmiller H. Ventral onlay urethroplasty using buccal mucosa for complex stricture repair. Urology 2003; 61 (5): 1004–1007, DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(02)02523-2.

- Turner-Warwick R. Prevention of complications resulting from pelvic fracture urethral injuries–and from their surgical management. Urol Clin North Am 1989; 16 (2): 335–358. DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(21)01515-9.

- Podesta M, Podesta MJ. Traumatic Posterior Urethral Strictures in Children and Adolescents. Front Pediatr 2019; 7: 24, DOI: 10.3389/fped.2019.00024.

- Hagedorn JC, Voelzke BB. Pelvic-fracture urethral injury in children. Arab J Urol 2015; 13 (1): 37–42, DOI: 10.1016/j.aju.2014.11.007.

- Koraitim MM. Posttraumatic posterior urethral strictures in children: a 20-year experience. J Urol 1997; 157 (2): 641–645. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65239-x.

- Colapinto V, McCallum RW. Injury to the male posterior urethra in fractured pelvis: a new classification. J Urol 1977; 118 (4): 575–580, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58110-0.

- Goldman SM, Sandler CM, Corriere JNJ, McGuire EJ. Blunt urethral trauma: a unified, anatomical mechanical classification. J Urol 1997; 157 (1): 85–89, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65291-1.

- Nerli RB, Koura AC, Ravish IR, Amarkhed SS, Prabha V, Alur SB. Posterior urethral injury in male children: long-term follow up. J Pediatr Urol 2008; 4 (2): 154–159, DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.11.002.

- Helmy TE, Hafez AT. Internal urethrotomy for recurrence after perineal anastomotic urethroplasty for posttraumatic pediatric posterior urethral stricture: could it be sufficient? J Endourol 2013; 27 (6): 693–696, DOI: 10.1089/end.2012.0592.

- Hsiao KC. Direct vision internal urethrotomy for the treatment of pediatric urethral strictures: analysis of 50 patients. J Urol 2003; 170 (3): 952–955, DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082321.98172.4e.

- Singla M. Posttraumatic Posterior Urethral Strictures in Children—Management and Intermediate-term Follow-up in Tertiary Care Center. Urology 2008; 72 (3): 540–543, DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.02.078.

Última actualización: 2023-02-22 15:40