20: Voiding Dysfunction

Este capítulo durará aproximadamente 39 minutos para leer.

Introduction

Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS), bladder and bowel dysfunction (BBD) or dysfunctional elimination syndrome are all terms that describe what are the common array of symptoms which range from overactive bladder syndrome (OAB), voiding postponement, stress incontinence, giggle incontinence to dysfunctional voiding aside from others.1 The impact of daytime wetting in children can be quite profound—with social, emotional and behavioral effect on daily life.2 From our understanding of OAB we know that if it continues over a prolonged period of time, we will see thickening of the bladder wall, which can have an lifelong impact. As patients become older, the consequences become more profound and require more of an effort to correct.3,4

From a pediatric urology perspective, the child with OAB is likely to becoming an adult OAB problems. This correlation has been seen in two published reports. In the first study Fitzgerald et al3 revealed that frequent daytime voiding in childhood correlated with adult urgency, and a correlation existed between childhood and adult nocturia. Childhood daytime incontinence and nocturnal enuresis were associated with a more than 2 fold increased association with adult urge incontinence. In addition, history of childhood urinary tract infection (UTI) correlated with adult UTI. In another study by Minassian et al involving 170 adult women they found that there was a higher prevalence of childhood voiding dysfunction in women who had urinary frequency, urgency, and stress or urge incontinence.4 They also noted that symptomatic patients had a greater likelihood of higher BMI. The trend has been to reassure parents that these problems are self-limiting and will resolve as the child matures. It appears that spontaneous resolution may not always occur and some children as they mature are better at compensating for their problems and eventually fail to follow up. A better understanding of the potential causes of childhood OAB can prevent undue problems in adulthood and make many children, parents and teachers much happier.

Genetics

Increasing evidence exists that genetic factors have a major role in urinary incontinence. Children of parents that have OAB and/or underlying psychiatric problems tend to be more refractory to conventional treatments of OAB.3,5 These findings have been corroborated by Labrie et al, whose research shows that mothers of children with OAB or dysfunctional voiding are more likely to have similar symptoms in childhood than mothers of children without LUT symptoms (28.9% vs 16.3% p<0.02, respectively).5 Fathers of children with LUT symptoms were more likely to have had delayed resolution of their nocturnal enuresis (6% and 6.5% boys and girls respectively) and also fathers who had daytime incontinence had a statistically significant rate of incontinence as children 9.25% vs 4.6% (p<0.0001).5 Adult data can be used as a proxy for children. Looking at the data available, some studies that indicate a genetic predisposition to LUTS for some patients. A commonly used methodology to ascertain the importance of genetic influence is the use of twin studies. A Swedish study involving over 25000 twins revealed evidence of a genetic link for susceptibility to urinary incontinence, frequency and nocturia in women.6 There was insufficient data in male patients to make any conclusions. On the other hand, in a study looking at a metanalysis of candidate polymorphism/genes in men they found five genes ACE, ELAC2, GSTM1, TERT, and VDR. The heterogeneity was high in three of these meta-analyses. The rs731236 variant of the vitamin D receptor had a protective effect for LUTS (odds ratio: 0.64; 95% confidence interval, 0.49–0.83) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 27.2%).7

When looking at the psychiatric literature there is a large number of studies linking psychological conditions and LUTS. The association of urinary incontinence and psychological well-being in adults has also been noted by Botlero et al.8 Major depression can predict the onset of urinary incontinence in women in an at-risk population based sample.9 One study found increased rates of enuresis in adult bipolar disorder (18%).10 An association with panic disorder and interstitial cystitis has also been described.11 Day wetting also was found to be a premorbid developmental marker for schizophrenia (SCZ).12 The authors found that patients with SCZ had higher rates of childhood enuresis (21%) compared with siblings (11%) or control patients (7%), and the relative risk for enuresis was increased in siblings. Patients with enuresis performed worse on two frontal lobe cognitive tests (letter fluency and category fluency) as compared with non-enuretic patients. Notably cerebral defects associated with these disorders tend to cluster around the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and prefrontal cortex (PFC) exactly where defects are being seen in patients with urgency and urge incontinence on fMRI.13,14

Epidemiology

The prevalence of daytime incontinence varies widely from study to study. By 7 years of age, daytime incontinence rate ranges from 4.9 to 11.7%.15,16 At 11–12 years of age, prevalence rate ranges between 0.8% and 12.5%.17,18,19,20,21 A meta-analysis of these 3 studies was performed resulting in an overall prevalence of 6.4%. The most important study shedding light on a continual basis is the English ALSPAC longitudinal study which found the following trajectories for daytime incontinence over the age range 4.5-9.5 years:22

i. Normative (86.2%); dry by 4.5 years ii. Delayed (6.9%); steadily decreasing probability of daytime incontinence from 80% at 4.5 years of age to < 10% at 9.5 years of age iii. Persistent (3.7%); probability of daytime incontinence > 80% until 7.5 years of age with steady reduction to 60% at 9.5 years of age iv. Relapsing (3.2%); probability of daytime incontinence <10% at 5.5 years of age increasing to 60% at 6.5 years with slow decline thereafter.

There was no gender difference in the delayed group but girls outnumbered boys in the persistent and relapsing groups. A study by Stone et al that evaluated children with persistent urinary incontinence who underwent urodynamic investigation and imaging of their spines revealed that, if extrapolated to 18 years of age, up to 33% of the children that were wetting at 10 years of age were likely to persist with some form of urinary symptoms.23

Neuropsychiatric Comorbidity

Children with elimination disorders have an increased rate of coexistent behavioral and psychological disorders; approximately 20–40% of children with daytime urinary incontinence are affected by behavioral disorders.24,25,26 In a large epidemiological study of 8213 children aged 7.5–9 years, children with daytime wetting had significantly increased rates of psychological conditions, especially separation anxiety (11.4%), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (24.8%), oppositional behavior (10.9%), and conduct problems (11.8%).27 In the same cohort, 10,000 children aged 4–9 years were evaluated; delayed development, difficult temperament, and maternal depression/anxiety were associated with daytime wetting and soiling.28 In another population-based study that included 2856 children, the incidence of incontinence was 16.9% within the previous 6 months.29 In a retrospective study of patients with ADHD, 20.9% wet at night and 6.5% wet during the day. The odds ratios were 2.7 and 4.5, respectively, which demonstrates a non-specific association of ADHD with nighttime and daytime wetting.30 Of the possible gastrointestinal elimination disorders, children with fecal incontinence (or encopresis) had the highest rates of comorbid behavioral disorders: 30–50% of all children had clinically relevant behavioral disturbances.24,25 In an epidemiological study of over 8242 children, those who were 7- to 8-years of age had a wide range of coexistent disorders (DSM-IV) including separation anxiety (4.3%), social phobias (1.7%), specific phobias (4.3%), generalized anxiety (3.4%), depressive disorders (2.6%), ADHD (9.2%), and oppositional defiant behavior (11.9%). A previous study found that patients described as having psychoneuroticism were less likely to respond to treatment of detrusor instability than those who had no form of psychoneuroticism. Most good responders and one third of non-responders were free of psychiatric issues.31 Of importance, 25% of the patients in this study had irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.

Evaluation

History

Evaluation of the child with BBD begins with detailed history and physical examination. A clear history helps determine prevailing symptomatology and when the symptoms tend to occur. Generally, it is best to try to obtain the pertinent history from the child if they are cooperative. When obtaining the history from the child is not possible, there may be no choice but to obtain it from the parents. Signs of urgency such as crossing the legs, running to the bathroom, grabbing the penis, rubbing the clitoris, squatting and sitting on the heels (Vincent’s curtsy) are all signs of urgency. Maintenance of a voiding diary is critical. Urinary frequency is another manifestation of OAB and quantifying the amount and number of times the patient voids is useful in determining if there is true frequency. Urinary urge incontinence is a classic hallmark of overactive bladder. The time at which incontinence occurs should be documented to help identify any association with the bowel. It is not uncommon in children with large stool burdens to have urgency and urge incontinence after a meal. This is most likely due to stimulation of colonic contractions by the gastrocolic reflex. It is well understood that there is cross talk occurring in the spinal cord between the colon and the bladder.32,33,34,35 This may trigger bladder contractions or at least lead to symptoms of urgency. Post void dribbling is a sign of either incomplete relaxation of the whole sphincter complex or the external sphincter. It is common in children with dysfunctional voiding. Also commonly seen in dysfunctional voiding patients is dysuria or urethrorrhagia that is not associated with infection but rather due to dyssynergic voiding.33

Internal sphincter dyssynergia has been associated with dizziness and autonomic dysfunction (hypotension on standing without concomitant increase in heart rate) for both males and females when patients are asked if they get dizzy on standing.36

A thorough history of the patient’s bowel habits should be obtained from the patient directly. Many parents are not cognizant of the true nature of their children's bowel movements and many will report that their children's bowel movements are normal while the children will steadfastly contradict them. Documentation of the size and nature of the bowel movements should be obtained. Use of a diagram is quite beneficial and it facilitates communication with the child.37 It is important to note if the bowel movements are painful or associated with rectal bleeding. Large massive bowel movements are usually an indicator of infrequent bowel movements. Pain or rectal bleeding can be associated with external sphincter dyssynergia. Patients who have diarrhea or symptoms of colitis can also have issues with overactive bladder. Chronic periumbilical pain is another sign that there is a problem with constipation or issues with serotonin homeostasis in the gut. Many children will complain of this pain and once a bowel regimen is instituted the pain goes away.

A standardized questionnaire should be used to evaluate patients when first seen and on follow up. There are 2 commonly used questionnaires that have been validated for children, the first is the DVSS and the other is the Vancouver Scale.38,39 Additionally, there is a questionnaire that evaluates the psychiatric makeup of the child and is quite useful to quickly screen for underlying attention, hyperactivity, depression and anxiety issues in children which are commonly associated with LUTS.40

Physical Examination

Physical examination is helpful in evaluation and can be very revealing. Examination of the abdomen is critical in determining whether there is palpable stool in the colon. Palpation of the left lower quadrant up to the left upper quadrant typically will yield large amounts of stool present in these abdomens. In many cases the parents may deny issues with their bowels. Gaseous distention of the colon is just as troublesome and should be noted since this can lead to the same problems as constipation.

Examination of the back will typically reveal a normal appearing back and anocutaneous folds. The rare instance of flattening of the buttocks or abnormal creasing at the SI joint is indicative of a sacral anomaly (Figure 1) and (Figure 2) Observing the child walk can also help identify a potential neurologic problem if the child performs toe walking. High arched feet are another potential clue to some form of neurologic condition. Low lying sacral dimples are typically not of concern. Only dimples that are associated with tuffs of hair or a placed higher up on the back are of concern and should be evaluated with an MRI of the lumbar-sacral spine.

Figure 1 Abnormal sacral cleft associated with tethered cord.

Figure 2 Parasacral appendage associated with cord thethering.

Diagnostic Testing

Below we discuss the diagnostic tests we perform in the order in which we perform them to optimize our management and minimize invasive testing in patients.

Urinalysis

The first and most important clinical test that should be performed in all children that present with BBD is the urinalysis. A simple urinalysis should help determine if the symptoms are due to infection or BBD. It is not uncommon to see microhematuria in patients that have dyssynergic voiding which is commonly associated with BBD.

Post Void Residual

A PVR should be done on all patients seen for LUTS and DV. This is the most important piece of information that you have to go on in the early stages of the evaluation and can give you further immediate insight into the potential issues that need to be addressed. Elevated residuals can be associated with recurrent UTIs or frequent voiding, while low PVR can be also associated with frequency, but the underlying etiology of the frequency will be different.

A device capable of providing a real image of the bladder is preferred over a device that gives a representative image. This is valuable since one can also measure rectal diameter. Rectal diameters in excess of 4 cm are associated with BBD and studies have shown correction of this dilation is associated with improvements in symptoms.

Uroflow/EMG

Uroflowmetry is an important tool in helping to determine if the child voids abnormally. The use of the 5 classic curves, bell, the tower or hypervoider, the staccato, interrupted and the plateau curve is in the process of being supplanted by a modified system that relies on whether the curve is smooth or fractionated and a flow index. The flow index is volume agnostic so therefore can be used to compare flows at all volumes and across multiple ages.41,42,43 Additionally flow indexes are a measure of voiding efficiency which is much more accurate representation of flow than shape descriptions.

The use of the uroflow is further augmented by the concomitant use of an EMG of the perineal muscles. Utilizing the perineal EMG allows us to determine if the child is voiding with external sphincter dyssynergia (increased perineal muscle activity) and to diagnose internal sphincter dyssynergia based on lag time and the shape of the flow curve (typically plateau or Flow index <=0.7).44

Renal and Bladder Ultrasonography

Renal-bladder ultrasound is not essential for children with LUTS not associated with infection. On the other hand, a patient with repeat infections should have the upper tracts examined to look for size discrepancies and hydronephrosis which could be indicative of reflux or consequences thereof. In patients with persistent incontinence an ultrasound is useful to rule out a duplication of the kidney associated with an ectopic ureter. Dilation of a ureter may be another clue to suggest an ectopic ureter. In patients with obstructive voiding, the bladder ultrasound is helpful in identifying the presence of an obstructing ureterocele. Bladder wall thickening can be discerned from the ultrasound and is a useful indicator of obstruction or overactivity.

KUB and AP Lateral of Spine

In some children where body habitus makes palpation of stool unreliable, it may be necessary to consider KUB to evaluate the colonic stool burden or to assess progress with a bowel regimen. If a KUB is performed, it is reasonable to consider an AP and lateral film of the sacrum to confirm that there are no sacral anomalies (Figure 3) In some children, a KUB can be inadequate to verify the spine is normal due to overlying stool obscuring the sacrum.

Figure 3 Lateral fim of spine clearly shows sacral segments that would not be visible due to large stool burden in this patient.

Voiding Cystourethrography

A well-tempered VCUG provides a tremendous amount of information on the dynamics of voiding in addition to the presence or absence of reflux, ectopic ureters or valves. The bladder neck can be seen opening and the external sphincter can also be seen as it opens and closes. The presence of the spinning top urethra is a classic example of external sphincter dyssynergia (Figure 4) A VCUG is not indicated in all patients with LUTS. A VCUG should be obtained in refractory cases to further delineate the dynamics of voiding and confirm no anatomic problem is missed.

Figure 4 Spinning top urethra in female with reflux and recurrent UTIs.

MRI of Spine

Sacral imaging is indicated when the patient has an obvious lesion of the back, as previously mentioned in the physical examination section. In patients who have failed all treatment attempts and incontinence persists an MRI of the spine may also be indicated. We recommend the MRI be completed prior to urodynamics since detrusor overacitivity on urodynamics is not diagnostic of neurogenic bladder dysfunction. Therefore, the patient will need an MRI of spine regardless and best to proceed with the definitive test first. Occult tethered cord occurs very infrequently when there is no cutaneous stigmata.45

Urodynamics

In patients with LUTS, urodynamic study often only confirms a thorough history that uninhibited contractions (UIC) are present. Bael et al justify this statement as they demonstrated there was no benefit to performing a urodynamic study in children with BBD.46 The presence of UICs does not rule in or out the presence of a neurologic lesion. The only finding of significance is the absence of a detrusor contraction already evident from the uroflow study demonstrating a poor flow curve. This is not to say that there is no indication to perform UDS in children. In some instances, urodynamics are performed simultaneously with VCUG. In some cases, UDS can help identify the source of the wetting especially when combined with fluoroscopy.

Treatment Options

Urotherapy

Urotherapy is an umbrella term for all non-surgical, non-pharmacological interventions for functional bladder and bowel problems in children and adolescents. It is the mainstay treatment for daytime urinary incontinence, as well as for nocturnal incontinence, functional constipation, and fecal incontinence.47,48

The goal of urotherapy is to normalize micturition and bowel pattern and to prevent further functional disturbances. A distinction is made between standard urotherapy and specific urotherapy. Three conditions must be met before urotherapy can start. First, a clear diagnosis of functional incontinence. Second, the child must be school-ready, when the child is too immature, he/she may not have the cognitive skills or motor abilities to understand and complete urotherapy. Third, a good psychosocial anamnesis as psychosocial or behavioral problems may also influence the effectiveness of therapy and may require psychiatric evaluation or family therapy.49,50

Standard urotherapy consists of education and demystification, behavioral modification instructions, lifestyle advice regarding fluid intake, registration of voiding frequencies, voiding volumes and incontinence episodes, and support and encouragement to children and their parents.51 Urotherapy starts with an explanation of bladder and bowel function and dysfunction, explaining the causes of incontinence. Instructions should be given on correct fluid intake and regular voiding during the day. Instruction as to proper toilet posture should also be provided. A bladder diary should be kept for self-monitoring and motivation. The diary provides the child and parents insight into treatment progress. After explanation and instructions, the child practices at home for a maximum of three months. During this period, frequent counseling should be provided and progressed should be assessed frequently. These interval assessments can be done by telemedicine and/or regular visits to the clinic.

Constipation or urinary tract infections (UTIs) should be addressed before urotherapy.47,48 As bowel and bladder dysfunction affect each other, urotherapy is less successful if bowel function and/or UTIs are not addressed during treatment.51,52

Successful treatment is determined by the degree that the child and parents are satisfied with the results. Satisfaction and improved quality of life may be a reason to end treatment instead of endeavoring the best results. When treatment is not successful, it is important to identify the reason.

When the results of standard urotherapy are unsatisfactory, specific urotherapy is recommended. This therapy combines specialist interventions such as biofeedback of the pelvic floor, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychotherapy, neuro-stimulation, or clean intermittent catheterization.47,48,51,53 Specific urotherapy is tailored to the specific type of bladder-bowel dysfunction and is composed of specific programs for children with treatment-resistant symptoms. These programs help children to learn how to void, when to void, and how often to void. Repeated practice is necessary to habituate the new voiding behavior.50

Children with behavioral problems require a tailored plan to the unique needs of the child.54 For comorbidities and severe bladder-overactivity, medication may be necessary.47

Urotherapy is an effective treatment that achieves continence in 56% of children within a year, whilst the spontaneous cure rate of incontinence is 15% per year. Urotherapy addresses all aspects of incontinence, leading to the best clinical outcome. This includes somatic, psychosocial, and behavioral problems and quality of life.55

Bowel Management

Acute, simple constipation or colonic distention in many cases may be addressed by simply increasing hydration and/or adding juices high in sorbitol, such as prune, pear and apple juice along with pureed fruits and vegetables to the child’s normal diet. Barley malt extract or corn syrup can also be used to soften stools. Other dietary changes include decreasing excessive milk intake as calcium saponifies the stool and leads to hardening. In addition, no evidence currently exists supporting the use of prebiotic and/or probiotic dietary supplements as a treatment of constipation.56 Following the failure of dietary interventions, other treatment options include osmotic laxatives such as polyethylene glycol (0.7 g/kg body weight per day) lactulose, sorbitol or milk of magnesia (dose: 1–3 mL/kg body weight per day). No evidence exists that dietary fiber supplementation or biofeedback alone are effective interventions for constipation that requires medical treatment.56 Many patients require maintenance therapy in order to manage their ongoing constipation symptoms. In our own experience, osmotic agents are not as effective alone as when used in combination with senna laxatives or bisacodyl. The concern that senna alkaloids are habit forming or impair colonic motility is an ‘old wives tale’ and should be ignored: aggressive use of such medications is warranted in some children.57

Use of osmotic agents by themselves has been borne out by Bush et al whose research showed that polyethylene glycol 350 was not superior to placebo during a 1-month trial.58 Management of constipation can result in up to a 50% resolution in voiding symptoms or greater.59

Pharmacological

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergics, (also known as antimuscarinics) are typically used as first-line treatments of OAB in children whose symptoms have persisted following urotherapy. Currently, only three antimuscarinics (oxybutynin [FDA and EMA] , Solfenacin [FDA and EMA] and tolterodine [EMA]) have formally received approval for use in children. The clinical trials that have been performed in children (oxybutynin, solifenacin, darifenacin studies) have generally included patients with proven neurogenic voiding problems and have not investigated the effects of antimuscarinics on patients with non-neurogenic, or idiopathic LUT symptoms. Data published in 2006 suggest that the therapeutic effects of antimuscarinics in patients considered to have no neurological deficits are mediated predominantly by interactions with the sensory/afferent limb of the reflex arc rather than with the efferent/motor side.60 Muscarinic receptors are found in urothelial cells, suburothelial cells of Cajal and on afferent nerves.61 Antimuscarinics are active during the filling/storage phase of micturition when the cholinergic (efferent or motor) nerves are not active. Acetylcholine can be generated and released from the urothelium as a response to bladder filling/increases in tension and also might ‘leak’ from the cholinergic nerve terminals during bladder filling62 followed by binding to M2 and M3 receptors and might be a mechanism of overactivity in patients with bladder diseases..63

Five distinct subtypes of muscarinic, cholinergic receptors have been identified (M1–M5), and the bladder smooth muscle predominantly expresses two of these subtypes: M2 (70–80%) and M3 (20–30%). Activation of M3 receptors has been demonstrated to evoke smooth muscle contraction, which is the primary stimulus for bladder contraction. M2 and M3 receptors have been postulated to be involved not only in activation of smooth muscle contraction by efferent nerves, but also in the activation of sensory/afferent nerves.61 The activation of M2 receptors in the urothelium might reverse the sympathetically mediated smooth muscle relaxation that enables the filling, or storage phase of the micturition cycle; although, activation of the M2 receptors might cause smooth muscle contraction through other poorly understood mechanisms.64

M1 receptors are found in the brain, glands (such as salivary glands), and sympathetic ganglia. Activation of these receptors’ accounts for most of the adverse effects of antimuscarinic drugs. Dry mouth is the most common symptom. Constipation, gastroesophageal reflux, blurred vision, urinary retention and cognitive side effects can also occur; these symptoms are generally less bothersome in children. The potential for adverse cognitive effects and delirium does also exist in children but is generally limited to overdosing situations.65,66,67 In clinical trials in adults, quantitative electroencephalographic data suggests that oxybutynin has more effects on the CNS than either trospium or tolterodine.68,69

Alpha Blockers

α-blockers (also known as α-adrenoceptor antagonists) on non-neuropathic voiding dysfunction was popularized by Austin et al to treat voiding dysfunction in children.70 These medications have been used in the management of patients with bladder-neck dysfunction and urinary retention, these agents are also useful in ameliorating the symptoms of urgency and urge incontinence in some children.71 Studies in adults indicate that alpha blockers are effective in managing irritative symptoms due to stents and in older men with benign prostatic hyperplasia.72,73 There is some evidence that alfuzosin reduced anal pressure at rest and during simulated evacuation in healthy and constipated women compared with placebo but did not improve bowel symptoms in constipated women.74 In many patients, terazosin, a non-selective α-blocker, is the first-line drug for treatment of urgency and increased urinary frequency, owing to the non-selective properties of this agent and the potential to cross the blood brain barrier; however, more-selective blockers of the α1-receptor such as tamsulosin or alfuzosin are better suited for the management of bladder neck dysfunction that can lead to detrusor hypertrophy and instability. Non-selective α-blockers can cause postural hypotension. Therefore, these agents must be used carefully, and a gradual titration of the dose is required. In patients with a family history of fainting easily or postural hypotension, dose titration is essential even with the use of more-selective α- blockers. For the most part, children tolerate α-blockers well.75

Beta-3 Agonists

Agonists of the β3 adrenoceptor, such as mirabegron can increase bladder capacity without increasing voiding pressure or post-void residual volume.76 Treatment with these agents leads to smooth muscle relaxation and the generally accepted mechanism of relaxation is via downstream activation of adenyl cyclase with the subsequent production of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) followed by inhibition of the Rho-kinase pathway.77,78 However, evidence also indicates that elevated cAMP also activates protein kinase A, which then activates large-conductance calcium-dependent K+ (BK) channels. Activation of these BK channels leads to hyperpolarization of bladder smooth muscle and increased detrusor stability.79 Mirabegron is approved for treatment of OAB in adults and children in the US and Europe.

Other Medications

Imipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant that affects both muscarinic receptors and α-adrenoceptors with a possible central effect on voiding reflexes.80 When imipramine was introduced to treat depression it was found to have marked effects on patients’ urinary incontinence. We have found imipramine to be an effective agent in controlling urge incontinence in some children who were previously found to be refractory to antimuscarinic therapy.81 The effects of imipramine on urinary incontinence might be the result of an effect in the frontal areas of the brain which are involved in executive functioning including control of urinary urgency. Alternatively, the urological effects of imipramine might reflect an effect on dopamine levels in the striatum thereby affecting ɣ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in the PAG. Increased GABA levels in the PAG impart suppression of the voiding reflex.82,83

Imipramine has also been found to be useful in treating our patients with giggle incontinence. Imipramine can cause postural hypotension and can also be dangerous in patients with cardiac conduction abnormalities and must be used with caution.

SSRIs and SNRIs

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to function at Onuf’s nucleus by modulating the voiding and storage reflexes which are dependent on glutamate. In the presence of glutamate, SSRIs augment the effects of incoming signals for bladder storage and also augment output to the external urethral sphincter thereby maintaining contraction of this sphincter. In the absence of glutamate, SSRIs have no effect upon signaling and normal parasympathetic activation resulting in contraction of the bladder and relaxation of the sphincter.84 This effect of SSRIs on the storage side of the reflex arc might explain how some patients’ bladder overactivity improves following treatment with SSRIs. These agents might also be acting in brain regions that are associated with processing of urgency signals, such as the ACG and PFC.

Electrical Stimulation

Sacral Neurostimulation

Sacral neurostimulation (also known as sacral neuromodulation) involves the placement of a wire lead into the S3 foramina and along the sacral nerve with subcutaneous implantation of a stimulator to provide continuous low-intensity stimulation of the nerve. Spinal cord stimulation is frequently used in adult patients and interest in the use of this approach in children is increasing. In a series of 20 prospectively monitored patients with dysfunctional elimination syndrome, described by Roth et al cessation of symptoms or a >50% improvement in symptoms occurred in 88% of children of whom 63% had nocturnal enuresis, 89% had increased daytime urinary frequency, and 59% had constipation. This group now has experience with sacral neurostimulation in 187 patients, with consistent outcomes.85,86

Parasacral Stimulation with Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

Parasacral stimulation involves the use of a TENS device and parasacral conducting pads, which are placed parasacrally in the S2–3 region while the electrodes are connected on the surface to a current generator. Studies have used stimulation at various frequencies, ranging from 10–80 Hz and frequencies of treatment ranging from weekly to daily. Durations of stimulation have also varied from 20 minutes up to 1 hour daily. Walsh et al first described the use of TENS in adults in 1999 followed by Hoebeke et al in 2001 who described usage in children.87,88 In subsequent studies, complete resolution of symptoms has ranged from 47–61.9% of children treated with this modality.89,90,91 This modality has also been found useful in stimulating bowel motility using cross inferential current.92

Tibial Peripheral Nerve Stimulation

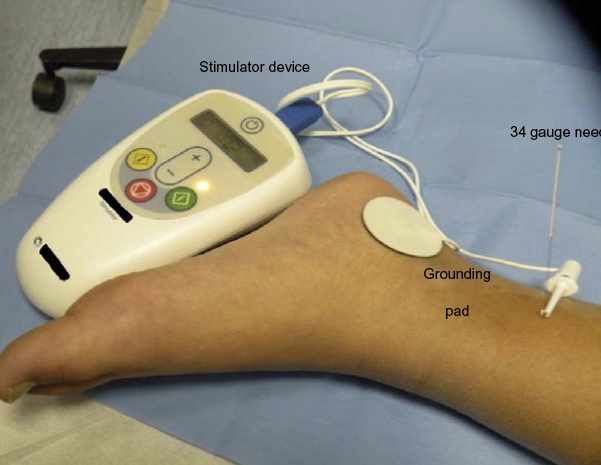

Percutaneous electrical tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS) is based on the traditional Chinese practice of using acupuncture points over the common peroneal posterior tibial nerves to inhibit bladder activity.87,88 One technique involves using a 34-gauge stainless steel needle, which is inserted approximately 5 cm cephalad to the medial malleolus, just posterior to the margin of the tibia. A stick-on electrode is placed on the medial surface of the calcaneus. This approach has been evaluated in clinical trials with variable results. Hoebeke et al reported that 17 out of 28 children whose OAB symptoms were refractory to medical treatment had either resolution or improvement of their symptoms in response to weekly 30-minute PTNS sessions.91 DeGennaro et al reported after long-term follow-up monitoring that 12 of 14 children with OAB and 14 of 14 with dysfunctional voiding were asymptomatic after two years.88 The authors did note that ‘chronic’ persistent long term PTNS use was required in 50% and 29% of children with OAB and dysfunctional voiding respectively to maintain these results. In a study that compared the efficacy of TENS delivered to the parasacral region with that of PTNS in children with OAB, significantly better outcomes were observed with use of TENS compared with PTNS (complete resolution observed in 70% versus 9% of patients, respectively; P = 0.02).93 Figure 5 shows such a device.

Figure 5 PTNS stimulation in a child.

Another form of tibial nerve stimulation is to apply patches over the nerve and stimulate the nerve like parasacral TENS. In a study comparing transcutaneous posterior tibial stimulation and sham stimulation in 40 children QoL scores, overall and day-time DVISS scores were significantly decreased in both sham and test groups (p < 0.05). Additionally, the frequency of incontinence and urgency episodes were also significantly reduced (p < 0.05) in the PTNS treatment group. This effect in the test group was still valid 2 years after intervention.94

Surgical Options

Botulinum Toxin A

Intravesical injections of botulinum toxin A (BoNT-A) into the detrusor have been approved for use in adults with OAB. A recent study published by Austin et al in neurogenic patients has proven safety of BoNT-A in children and resulted in FDA approval in children with NDO.95 In adults, BoNT-A injections have proven a useful treatment of patients with refractory OAB and offer an alternative to patients that cannot tolerate anticholinergic therapy. Limited published studies are available on the use of BoNT-A in children primarily consisting of nonrandomized selected clinical cohorts of neurologically healthy children with treatment refractory OAB and urge incontinence.96,97,98 The dose of BoNT-A is variable in these studies and ranges from 50–200 units.96,97,98 The follow-up data from these three studies, total of 55 patients, reveal that a full response defined by complete continence was achieved in 38–70% of these children after a single, or repeat injections. Few clinically significant adverse events were reported; one patient had a UTI and one patient had temporary urinary retention.96,97

Biofeedback

Biofeedback is the process of gaining greater awareness of pelvic floor muscle/sphincter action using external instruments that provide information about the action of these muscles with the goal of increasing awareness and voluntary control by the child.

Within specific urotherapy, the focus is often on pelvic floor rehabilitation using biofeedback training. The theoretical benefit of biofeedback is that children are able to directly visualize the activity of their pelvic floor muscles by EMG or uroflow curve.99 This facilitates defecation and helps the child to get awareness of pelvic floor muscle (contraction vs relaxation). In dysfunctional voiding due to external sphincter dyssynergia the aim is to achieve relaxed unobstructed voiding and complete bladder emptying. Feedback can be given immediately about performance as with EMG or ultrasound or knowledge of results as with uroflowmetry and post void residual measurement.100

The feedback from EMG can be used to teach the child to contract and relax the pelvic floor muscles at will.99 Using real time flowmetry helps the child to observe the flow curve during voiding. Children can be taught to urinate with a relaxed pelvic floor muscle and normal urine volume by achieving a continuous, bell-shaped flow curve. Ultrasound can be used to check if the bladder is empty after urination and report this to the child.

The impact of biofeedback in dysfunctional voiders who have reflux is significant in that we saw 60% spontaneous resolution of reflux in children 6 years and older treated with biofeedback.101 Some have claimed that biofeedback is effective for urgency as well its mechanism may be via reduction of the outlet resistance during voiding which leads to detrusor hypertrophy thereby leading to detrusor instability. On the other hand there are studies in adults that indicate it may be effective in OAB patients due to the continual one to one therapy received by the patient and improvement in the mental well-being of the patient.102

Biofeedback therapy is limited by the ability of the child to cooperate with the healthcare provider running the session. Children younger than five years of age typically are incapable of doing biofeedback on a regular basis. Children with significant learning disabilities, behavior problems and other neurologic problems are not ideal candidates for biofeedback. Additional studies reveal that biofeedback therapy is useful in the elimination of reflux in children that exhibit evidence of external sphincter dyssynergia.103,104

It is a misunderstanding that biofeedback alone is sufficient to achieve continence. In practice, professionals inadvertently combine biofeedback with education and instructions. By doing this, they also provide behavioral modification whilst thinking that they only provide biofeedback training. In urotherapy, biofeedback is merely one of the elements of treatment, type of biofeedback is not a decisive factor in treatment outcome.51

Disorders

Overactive Bladder

Evaluation and Diagnosis

The hallmark of OAB is urgency and by definition, children with this symptom can be said to have an OAB. Incontinence and increased voiding frequency are often present. Urge incontinence simply means incontinence in the presence of urgency and is applicable to many children with OAB. There is mounting evidence that OAB is a sensory problem; whether it is located in the central nervous system (CNS) or at the bladder level is a matter for debate. Children with incontinence not associated with a sudden urge to void or who are late to recognize the urge are more likely to have a neurologic problem or are more likely to have an issue with frontal lobe processing such as ADHD.

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Urotherapy, bowel program

- Avoid diarrhea or fecal accidents with poorly controlled or over aggressive use of osmotic agents and cathartics

- Avoid excessive gas from overloading with fiber; gas is just as detrimental as constipation and results in distention of the gut

- Fiber supplementation without water leads to worsening of the constipation

- Anticholinergics or Terazosin or Doxazosin

- Dry mouth or memory problems can be due to anticholinergic medications. Watch for constipation becoming worse with anticholinergics

- Dizziness and fatigue due to alpha blockers can be prevented by ensuring patients hydrate and increase salt intake.

- Evaluate for neuropsychiatric problems and treating accordingly

- SSRIs can be associated with irritability and suicidal thoughts

- Sympathomimetics for ADHD can lead to tightening of the bladder neck and potential negative effects on flow rates and even dysuria. Weight loss and constipation are associated with sympathomimetics.

- Consider PTNS or TENS

- Some children have a fear of needles and PTNS is not feasible

- Some children can overreact to the sensation and not tolerate therapy

- If resistant, can consider imipramine if failed treatments

- Can be associated with irritability and suicidal thoughts

- Can unmask bipolar disorder especially if a family history exists

- Do not give the medication to patients with a familial history of conduction defects or sudden cardiac death

- Medication must be under control of an adult at all times

- If no evidence of elevated residuals can consider Botulinum Toxin A injections to detrusor

- Patients with flow indexes below 0.3 or elevated residuals >150 cc should not receive Botulinum Toxin A injections due to the possibility of retention/CIC

- If all else fails can consider sacral neuromodulation

- Complications with lead displacement

Dysfunctional Voiding

Evaluation and Diagnosis

The child with dysfunctional voiding habitually contracts the urethral sphincter during voiding. Uroflowmetry with EMG is necessary to confirm the presence of sphincter contraction during voiding. Note that the term describes malfunction during the voiding phase only. The term dysfunctional voiding is independent of the storage phase. It is entirely possible for a child to experience dysfunctional voiding and storage symptoms such as incontinence, urgency or frequency thereby presenting two issues that require correction.

Treatment Options and Their Pitfalls

- Urotherapy, bowel program

- Avoid diarrhea or fecal accidents with poorly controlled or over aggressive use of osmotic agents and cathartics

- Avoid excessive gas from overloading with fiber; gas is just as detrimental as constipation and results in distention of the gut

- Fiber supplementation without water leads to worsening of the constipation

- Behavioral problems, like ADHD and ASS

- Even if the child seems cooperative, an avoidant attitude towards correct voiding behavior can still prevail, failing to make the real effort needed to achieve the result.

- Urinary tract infections

- Repeat uroflowmetry and confirm if the problem persists

- If etiology is external sphincter dyssynergia (ESS)

- Biofeedback

- Timed voiding to prevent infrequent voiding

- Manage detrusor overactivity if present. If overactivity is not adequately managed patients will continue to have urgency which will undo the biofeedback performed.

- If etiology is internal sphincter dyssynergia (ISS)

- Alpha blockers

- Dizziness and fatigue due to alpha blockers can be prevented by ensuring patients hydrate well and increase salt intake.

- If evidence of ESS, treat with biofeedback

- Continue bowel regimen

- Manage detrusor overactivity if present

- Anticholinergics or Terazosin or Doxazosin

- problems with dry mouth or memory problems can be due to anticholinergic medications. Watch for constipation becoming worse with anticholinergics.

- Dizziness and fatigue due to alpha blockers can be prevented by ensuring patients hydrate well and increase salt intake.

- Anticholinergics or Terazosin or Doxazosin

- Alpha blockers

Bulbar Urethritis/Urethrorrhagia

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Pain associated with voiding is commonly seen in patients with some form of dyssynergic voiding. In patients who have bulbar urethritis (dysuria/urethrorrhagia syndrome), the pain at the tip or along the shaft of the penis is most likely due to dyssynergic voiding. Correction of the voiding pattern eliminated the symptoms.33 In girls, vaginal or urethral pain can also indicate an abnormal pattern.

Underactive Bladder

Evaluation and Diagnosis

The old entity “lazy bladder” has replaced by the neutral term underactive bladder and is reserved for children with low voiding frequency and a need to increase intra-abdominal pressure to initiate, maintain or complete voiding (i.e., strainin). Children often produce an interrupted pattern on uroflowmetry. Formal diagnosis is confirmed with the use of urodynamics that demonstrate low voiding pressures. Unfortunately, there are no formal definitions for normal voiding pressures in children so we tend to use the pressures for adults.

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Evaluations will include a uroflowmetry with pelvic floor EMG and if possible a second abdominal muscle EMG.

- If abdominal straining is evident with a weak inefficient flow rate (flow index <0.7) and elevated postvoid residual, consider the diagnosis of UAB.

- Confirm with urodynamics

- Start urotherapy

- Consider alpha blockers to help open bladder neck and improve emptying

- Up to 50% of patients also have OAB and need treatment of OAB to prevent incontinence or recurrent UTIs

- ISS is commonly seen in UAB patients and treatment with alpha blockers is necessary in these patients.

- Consider CIC if patients have high PVR and or have recurrent UTIs; some have utilized sacral neuromodulation but with limited success

Pollakiuria

Evaluation and Diagnosis

This term applies to children who void often and with small volumes during the daytime only. Daytime voiding frequency is at least once hourly and average voided volumes are less than 50% of estimated bladder capacity (EBC), usually much smaller. Incontinence is not a usual or necessary ingredient in the condition and nocturnal bladder behavior is normal for the age of the child. The term is applicable from the age of daytime bladder control or 3 years.

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Evaluate the environment, commonly seen when a recent life event has occurred or there is an upcoming event such as the start of school, camp or holiday

- Make sure there is no new constipation or change in diet

- Initiate urotherapy, bowel program

- Avoid diarrhea or fecal accidents with poorly controlled or over aggressive use of osmotic agents and cathartics

- Avoid excessive gas from overloading with fiber; gas is just as detrimental as constipation and results in distention of the gut

- Fiber supplementation without water leads to worsening of the constipation

- Consider Anticholinergics or Terazosin or Doxazosin

- Dry mouth or memory problems can be due to anticholinergic medications. Watch for constipation becoming worse with anticholinergics

- Dizziness and fatigue due to alpha blockers can be prevented by ensuring patients hydrate well and increase salt intake.

- Evaluate for neuropsychiatric problems if present consider treating accordingly

- SSRIs can be associated with irritability and suicidal thoughts

- Sympathomimetics for ADHD can lead to tightening of bladder neck and potential negative effects on flow rates and even dysuria. Weight loss and constipation are associated with sympathomimetics.

- Can resolve spontaneously

Giggle Incontinence

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Giggle incontinence is associated with complete voiding which occurs specifically during or immediately after laughing. Bladder function is normal when the child is not laughing. Giggle incontinence is clearly different than stress incontinence where voiding can be prevented or stopped volitionally.

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Confirm the diagnosis with a good history

- Commonly seen in children with underlying neuropsychiatric disorders

- Urotherapy and bowel regimen to make sure that this is not simple OAB

- If no response, then initiate therapy

- Imipramine: Initiate dosing at 10 mg and increase to max of 75 mg

- Atomoxetin: Initiate dosing at 10 mg and increase accordingly

- Sympathomimetics: Dosing depends on medication chosen, should be long-acting version otherwise the patient is at risk of accidents when the medication wears off

- SSRIs: Dosing is dependent on medication, chose the lowest dose and gradually escalate.

- All the above carry the same problems

- can be associated with irritability and suicidal thoughts

- can unmask bipolar disorder if a family history exists

- do not give the medication to patients with a familial history of conduction defects or sudden cardiac death

- Medication must be under control of an adult at all times

Vaginal Voiding

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Toilet trained prepubertal girls who wet their underwear within 10 minutes of voiding likely to be experiencing vaginal reflux if no underlying mechanism other than vaginal entrapment of urine is obvious. Vaginal voiding is not associated with other LUT symptoms. It is essential to differentiate vaginal voiding from post void dribbling since the treatment is quite different.

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Confirm the diagnosis and differentiate from post void dribbling, stress and urge incontinence

- Commonly seen in young girls who do not pull clothes below the knee

- Commonly seen in girls who have prominent labial fat

- Commonly seen in girls who are obese

- Recommend patients sit on toilet with legs spread and thighs apart or sit facing the wall behind the toilet which forces the legs to be spread

- Frequently is associated with vaginal discharge and vaginitis

- Can be associated with lichen sclerosis of the labia

Stress Incontinence

Evaluation and Diagnosis

Stress incontinence is the leakage of small amounts of urine at exertion or with increased intraabdominal pressure, typically associated with valsalva. It is rare in neurologically normal children. There is an increased association with hyperflexible girls involved in gymnastics and dance.105

Treatment Options and Pitfalls

- Confirm diagnosis and differentiate from post void dribbling, stress and urge incontinence

- Surgical correction with open or laparoscopic burch106,107

Key Points

Conclusions

asdf

References

- Ruarte AC, E Q. Urodynamic Evaluation in Normal Children. J Urol 1987; 127 (4): 831–831. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)54062-8.

- Landgraf JM, Abidari J, Cilento BG, Cooper CS, Schulman SL, Ortenberg J. Coping, Commitment, and Attitude: Quantifying the Everyday Burden of Enuresis on Children and Their Families. Pediatrics 2004; 113 (2): 334–344. DOI: 10.1542/peds.113.2.334.

- Rovner ES. Childhood Urinary Symptoms Predict Adult Overactive Bladder Symptoms. Yearbook of Urology 2006; 2007: 65–66. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(08)70046-0.

- Minassian VA, Lovatsis D, Pascali D, Alarab M, Drutz HP. The Effect of Childhood Dysfunctional Voiding on Urinary Incontinence in Adult Women. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107 (Supplement): 47s. DOI: 10.1097/00006250-200604001-00112.

- Labrie J, Jong TPVM de, Nieuwhof-Leppink A, Deure J van der, Vijverberg MAW, Vaart CH van der. The Relationship Between Children With Voiding Problems and Their Parents. J Urol 2010; 183 (5): 1887–1891. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.01.004.

- Wennberg A-L, Altman D, Lundholm C, Klint Å, Iliadou A, Peeker R, et al.. Genetic Influences Are Important for Most But Not All Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: A Population-Based Survey in a Cohort of Adult Swedish Twins. Eur Urol 2011; 59 (6): 1032–1038. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.03.007.

- Kaplan SA. Re: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Candidate Gene Association Studies of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms in Men. J Urol 2014; 195 (6): 1839–1840. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.03.051.

- Botlero R, Bell RJ, Urquhart DM, Davis SR. Urinary incontinence is associated with lower psychological general well-being in community-dwelling women. Menopause 2010; 17 (2): 332–337. DOI: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ba571a.

- Melville JL, Fan M-Y, Rau H, Nygaard IE, Katon WJ. Major depression and urinary incontinence in women: temporal associations in an epidemiologic sample. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009; 201 (5): 490.e1–490.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.05.047.

- Henin A, Biederman J, Mick E, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Sachs GS, Wu Y, et al.. Childhood antecedent disorders to bipolar disorder in adults: A controlled study. J Affect Disord 2007; 99 (1-3): 51–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.09.001.

- Weissman MM, Gross R, Fyer A, Heiman GA, Gameroff MJ, Hodge SE, et al.. Interstitial Cystitis and Panic Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61 (3): 273. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.3.273.

- Stockman JA. Enuresis as a premorbid developmental marker of schizophrenia. Yearbook of Pediatrics 2008; 2010: 396–398. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-3954(09)79524-7.

- Fowler CJ, Griffiths DJ. A decade of functional brain imaging applied to bladder control. Neurourol Urodyn 2010; 29 (1): 49–55. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20740.

- Fowler CJ, Griffiths D, Groat WC de. The neural control of micturition. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9 (6): 453–466. DOI: 10.1038/nrn2401.

- Hansen A, Hansen B, Dahm TL. Urinary tract infection, day wetting and other voiding symptoms in seven-to eight-year-old Danish children. Acta Paediatr 1997; 86 (12): 1345–1349. DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1997.tb14911.x.

- Hellström A-L, Hanson E, Hansson S, Hjälmås K, Jodal U. Micturition habits and incontinence in 7-year-old Swedish school entrants. Eur J Pediatr 1990; 149 (6): 434–437. DOI: 10.1007/bf02009667.

- Lee SD, Sohn DW, Lee JZ, Park NC, Chung MK. An epidemiological study of enuresis in Korean children. BJU Int 2000; 85 (7): 869–873. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00617.x.

- Safarinejad MR. Prevalence of nocturnal enuresis, risk factors, associated familial factors and urinary pathology among school children in Iran. J Pediatr Urol 2007; 3 (6): 443–452. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2007.06.001.

- Wekke J Spee-van der, Hirasing RA, Meulmeester JF, Radder JJ. Childhood Nocturnal Enuresis in the Netherlands. Urology 1998; 51 (6): 1022–1026. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00106-x.

- Swithinbank LV, Brookes ST, Shepherd AM, Abrams P. The natural history of urinary symptoms during adolescence. BJU Int 1998; 81 (s3): 90–93. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1998.00016.x.

- Deshpande AV, Craig JC, Smith GHH, Caldwell PHY. Management of daytime urinary incontinence and lower urinary tract symptoms in children. J Paediatr Child Health 2003; 48 (2): E44–e52. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02216.x.

- Heron J, Joinson C, Croudace T, Gontard A von. Trajectories of Daytime Wetting and Soiling in a United Kingdom 4 to 9-Year-Old Population Birth Cohort Study. J Urol 2008; 179 (5): 1970–1975. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.01.060.

- Stone JJ, Rozzelle CJ, Greenfield SP. Intractable Voiding Dysfunction in Children With Normal Spinal Imaging: Predictors of Failed Conservative Management. Urology 2010; 75 (1): 161–165. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.100.

- Tekgul S, R. N, Hoebeke P, Canning D, Bower W, Gontard A. Incontinence. 2009: 701–792.

- Gontard A, Nevéus T. Management of disorders of bladder and bowel control in childhood. 2006. DOI: 10.1136/adc.2006.110023.

- Gontard A, Hussong J, Yang SS, Chase J, Franco I, Wright A. Neurodevelopmental disorders and incontinence in children and adolescents: Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and intellectual disability–A consensus document of the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2021; 41 (1): 102–114. DOI: 10.1002/nau.24798.

- Joinson C, Heron J, Butler U, Gontard A von, Parents the Avon Longitudinal Study of, Team CS. Psychological Differences Between Children With and Without Soiling Problems. Pediatrics 2006; 117 (5): 1575–1584. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1773.

- Joinson C, Heron J, Gontard A von, Butler U, Golding J, Emond A. Early Childhood Risk Factors Associated with Daytime Wetting and Soiling in School-age Children. J Pediatr Psychol 2008; 33 (7): 739–750. DOI: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn008.

- Sureshkumar P, Jones M, Cumming R, Craig J. A Population Based Study of 2,856 School-Age Children With Urinary Incontinence. J Urol 2009; 181 (2): 808–816. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.044.

- ROBSON WMLANEM, JACKSON HAROLDP, BLACKHURST DAWN, LEUNG ALEXANDERk. C. Enuresis in Children With Attention–Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. South Med J 1997; 90 (5): 503–505. DOI: 10.1097/00007611-199705000-00007.

- MOORE KATEH, SUTHERST JR. Response to Treatment of Detrusor Instability in Relation to Psychoneurotic Status. Br J Urol 1990; 66 (5): 486–490. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1990.tb14993.x.

- WARNE STEPHANIEA, GODLEY MARGARETL, WILCOX DUNCANT. Surgical Reconstruction Of Cloacal Malformation Can Alter Bladder Function: A Comparative Study With Anorectal Anomalies. J Urol 2381; 172 (6 Part 1): 2377–2381. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000145201.94571.67.

- Coplen DE. Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome as an Etiology of Idiopathic Urethritis in Childhood. Yearbook of Urology 2005; 2006: 257–258. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(08)70411-1.

- Pezzone MA, Liang R, Fraser MO. A Model of Neural Cross-Talk and Irritation in the Pelvis: Implications for the Overlap of Chronic Pelvic Pain Disorders. Gastroenterology 2005; 128 (7): 1953–1964. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.008.

- Ustinova EE, Fraser MO, Pezzone MA. Colonic irritation in the rat sensitizes urinary bladder afferents to mechanical and chemical stimuli: an afferent origin of pelvic organ cross-sensitization. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006; 290 (6): F1478–f1487. DOI: 10.1152/ajprenal.00395.2005.

- Franco I, Grantham EC, Cubillos J, Franco J, Collett-Gardere T, Zelkovic P. Can a simple question predict prolonged uroflow lag times in children? J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (3): 157.e1–157.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.12.009.

- Lewis SJ, Heaton KW. Stool Form Scale as a Useful Guide to Intestinal Transit Time. Scand J Gastroenterol 1997; 32 (9): 920–924. DOI: 10.3109/00365529709011203.

- FARHAT WALID, B??GLI DARIUSJ, CAPOLICCHIO GIANPAOLO, O???REILLY SHEILA, MERGUERIAN PAULA, KHOURY ANTOINE, et al.. The Dysfunctional Voiding Scoring System: Quantitative Standardization Of Dysfunctional Voiding Symptoms In Children. J Urol 2000; 164: 1011–1015. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00023.

- Afshar K, Mirbagheri A, Scott H, MacNeily AE. Development of a Symptom Score for Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome. J Urol 2009; 182 (4s): 1939–1944. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.009.

- Van Hoecke E, Baeyens D, Vanden Bossche H, Hoebeke P, Vande Walle J. Early Detection of Psychological Problems in a Population of Children With Enuresis: Construction and Validation of the Short Screening Instrument for Psychological Problems in Enuresis. J Urol 2007; 178 (6): 2611–2615. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.025.

- Franco I, Shei-Dei Yang S, Chang S-J, Nussenblatt B, Franco JA. A quantitative approach to the interpretation of uroflowmetry in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2016; 35 (7): 836–846. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22813.

- Franco I, Franco JA, Nussenblatt B. Can the idealized voider derived flow indexes be a measure of voiding efficiency and how accurate are they? Neurourol Urodyn 2018; 37 (6): 1913–1924. DOI: 10.1002/nau.23585.

- Franco I, Franco J, Lee YS, Choi EK, Han SW. Can a quantitative means be used to predict flow patterns: Agreement between visual inspection vs. flow index derived flow patterns. J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (4): 218.e1–218.e8. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.05.026.

- COMBS ANDREWJ, GRAFSTEIN NEIL, HOROWITZ MARK, GLASSBERG KENNETHI. Primary Bladder Neck Dysfunction In Children And Adolescents I: Pelvic Floor Electromyography Lag Time–a New Noninvasive Method To Screen For And Monitor Therapeutic Response. J Urol 2005; 173 (1): 207–211. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000147269.93699.5a.

- Tuite GF, Thompson DNP, Austin PF, Bauer SB. Evaluation and management of tethered cord syndrome in occult spinal dysraphism: Recommendations from the international children’s continence society. Neurourol Urodyn 2018; 37 (3): 890–903. DOI: 10.1002/nau.23382.

- Coplen DE. The Relevance of Urodynamic Studies for Urge Syndrome and Dysfunctional Voiding: A Multicenter Controlled Trial in Children. Yearbook of Urology 2008; 2009: 83–84. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(09)79276-0.

- Birder LA. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Treatment of daytime urinary incontinence: A standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2017; 36: 43–50, DOI: 10.3410/f.725854188.793540473.

- Yang S, Chua ME, Bauer S, Wright A, Brandström P, Hoebeke P, et al.. Diagnosis and management of bladder bowel dysfunction in children with urinary tract infections: a position statement from the International Children’s Continence Society. Pediatr Nephrol 2018; 33 (12): 2207–2219. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-017-3799-9.

- Gontard A von, Kuwertz-Bröking E. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Enuresis and Functional Daytime Urinary Incontinence. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019; 116: 279–285, DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2019.0279.

- MacNeily AE. Should Psychological Assessment be a Part of Incontinence Management in Children and Adolescents? J Urol 2016; 195 (5): 1327–1328. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.02.071.

- Nieuwhof-Leppink AJ, Hussong J, Chase J, Larsson J, Renson C, Hoebeke P, et al.. Definitions, indications and practice of urotherapy in children and adolescents: - A standardization document of the International Children’s Continence Society (ICCS). J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (2): 172–181. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.11.006.

- Borch L, Hagstroem S, Bower WF, Siggaard Rittig C, Rittig S. Bladder and bowel dysfunction and the resolution of urinary incontinence with successful management of bowel symptoms in children. Acta Paediatr 2013; 102 (5): e215–e220. DOI: 10.1111/apa.12158.

- Hagstroem S, Mahler B, Madsen B, Djurhuus JC, Rittig S. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation for Refractory Daytime Urinary Urge Incontinence. J Urol 2009; 182 (4s): 2072–2078. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.05.101.

- Niemczyk J, Equit M, Hoffmann L, Gontard A von. Incontinence in children with treated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr Urol 2015; 11 (3): 141.e1–141.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2015.02.009.

- Schäfer SK, Niemczyk J, Gontard A von, Pospeschill M, Becker N, Equit M. Standard urotherapy as first-line intervention for daytime incontinence: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2018; 27 (8): 949–964. DOI: 10.1007/s00787-017-1051-6.

- Medina-Centeno R. Medications for constipation in 2020. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020; 32 (5): 668–673. DOI: 10.1097/mop.0000000000000938.

- Wald A. Constipation. Jama 2016; 315 (2): 185. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2015.16994.

- Cruz F. Faculty of 1000 evaluation for Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of polyethylene glycol (MiraLAX(®)) for urinary urge symptoms. F1000 - Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2013; 9: 597–604, DOI: 10.3410/f.717964565.793474432.

- Loening-Baucke V. Urinary Incontinence and Urinary Tract Infection and Their Resolution With Treatment of Chronic Constipation of Childhood. Pediatrics 1997; 100 (2): 228–232. DOI: 10.1542/peds.100.2.228.

- Finney SM, Andersson KE, Gillespie JI, Stewart LH. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Antimuscarinic drugs in detrusor overactivity and the overactive bladder syndrome: motor or sensory actions? Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2006; 98: 503–507, DOI: 10.3410/f.1040721.489750.

- Andersson K-E. Antimuscarinic Mechanisms and the Overactive Detrusor: An Update. Eur Urol 2011; 59 (3): 377–386. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.11.040.

- Wein AJ, Rackley RR. Overactive Bladder: A Better Understanding of Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. J Urol 2006; 175 (3s): 5–10, DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)00313-7.

- Kullmann FA, Artim DE, Birder LA, Groat WC de. Activation of Muscarinic Receptors in Rat Bladder Sensory Pathways Alters Reflex Bladder Activity. J Neurosci 2008; 28 (8): 1977–1987. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.4694-07.2008.

- Andersson K. Step-by-Step Guide to Treatment of Overactive Bladder (OAB)/Detrusor Overactivity. Urogynecology: Evidence-Based Clinical Practice 2004; 2: 77–91. DOI: 10.1007/1-84628-165-2_7.

- Ferrara P, D’Aleo CM, Tarquini E, Salvatore S, Salvaggio E. Side-effects of oral or intravesical oxybutynin chloride in children with spina bifida. BJU Int 2001; 87 (7): 674–678. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02152.x.

- SOMMER BARBARAR, O’HARA RUTH, ASKARI NUSHA, KRAEMER HELENAC, KENNEDY WILLIAMA. The Effect Of Oxybutynin Treatment On Cognition In Children With Diurnal Incontinence. J Urol 2AD; 173 (6): 2125–2127. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000157685.83573.79.

- Giramonti KM, Kogan BA, Halpern LF. The effects of anticholinergic drugs on attention span and short-term memory skills in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2008; 27 (4): 315–318. DOI: 10.1002/nau.20507.

- Todorova A, Vonderheid-Guth B, Dimpfel W. Effects of Tolterodine, Trospium Chloride, and Oxybutynin on the Central Nervous System. J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 41 (6): 636–644. DOI: 10.1177/00912700122010528.

- GUPTA S, SATHYAN G, LINDEMULDER E, HO P, SHEINER L, AARONS L. Quantitative characterization of therapeutic index: Application of mixed-effects modeling to evaluate oxybutynin dose–efficacy and dose–side effect relationships. Clin Pharmacol Ther 1999; 65 (6): 672–684. DOI: 10.1016/s0009-9236(99)90089-9.

- AUSTIN PAULF, HOMSY YVESL, MASEL JONATHANL, CAIN MARKP, CASALE ANTHONYJ, RINK RICHARDC. alpha-ADRENERGIC BLOCKADE IN CHILDREN WITH NEUROPATHIC AND NONNEUROPATHIC VOIDING DYSFUNCTION. J Urol 1999; 162: 1064–1067. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199909000-00029.

- Franco I, S. C, Collett T, Reda E. Unknown. American Academy of Pediatrics Meeting. San Francisco, CA: 2007.

- Dellis AE, Keeley FX, Manolas V, Skolarikos AA. Role of \ensuremathα-blockers in the Treatment of Stent-related Symptoms: A Prospective Randomized Control Study. Urology 2014; 83 (1): 56–62. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2013.08.067.

- Lepor H, Kaplan SA, Klimberg I, Mobley DF, Fawzy A, Gaffney M, et al.. Doxazosin for Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: Long-term Efficacy and Safety in Hypertensive and Normotensive Patients. J Urol 1997; 157 (2): 525–530. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65193-0.

- Chakraborty S, Feuerhak K, Muthyala A, Harmsen WS, Bailey KR, Bharucha AE. Effects of Alfuzosin, an \ensuremathα1-Adrenergic Antagonist, on Anal Pressures and Bowel Habits in Women With and Without Defecatory Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 17 (6): 1138–1147.e3. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.08.036.

- VanderBrink BA, Gitlin J, Toro S, Palmer LS. Effect of Tamsulosin on Systemic Blood Pressure and Nonneurogenic Dysfunctional Voiding in Children. J Urol 2009; 181 (2): 817–822. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.10.045.

- Andersson K. Ch. 8. Incontinence 2009.

- Uchida H, Shishido K, Nomiya M, Yamaguchi O. Involvement of cyclic AMP-dependent and -independent mechanisms in the relaxation of rat detrusor muscle via \ensuremathβ-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2005; 518 (2-3): 195–202. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.06.029.

- Frazier EP, Mathy M-J, Peters SLM, Michel MC. Does Cyclic AMP Mediate Rat Urinary Bladder Relaxation by Isoproterenol? J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2005; 313 (1): 260–267. DOI: 10.1124/jpet.104.077768.

- Kobayashi H, Adachi-Akahane S, Nagao T. Involvement of BKCa channels in the relaxation of detrusor muscle via \ensuremathβ-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 2000; 404 (1-2): 231–238. DOI: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00606-3.

- Hunsballe JM, Djurhuus JC. Clinical options for imipramine in the management of urinary incontinence. Urol Res 2001; 29 (2): 118–125. DOI: 10.1007/s002400100175.

- Franco I, Arlen AM, Collett-Gardere T, Zelkovic PF. Imipramine for refractory daytime incontinence in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Urol 2018; 14 (1): 58.e1–58.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2017.08.016.

- Groat WC de, Griffiths D, Yoshimura N. Neural Control of the Lower Urinary Tract. Compr Physiol 2015; 5: 327–396. DOI: 10.1002/cphy.c130056.

- Numata A, Iwata T, Iuchi H, Taniguchi N, Kita M, Wada N, et al.. Micturition-suppressing region in the periaqueductal gray of the mesencephalon of the cat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2008; 294 (6): R1996–r2000. DOI: 10.1152/ajpregu.00393.2006.

- Schuessler B. What do we know about duloxetine’s mode of action? Evidence from animals to humans. Bjog 2006; 113: 5–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.00877.x.

- Roth TJ, Vandersteen DR, Hollatz P, Inman BA, Reinberg YE. Sacral Neuromodulation for the Dysfunctional Elimination Syndrome: A 10-Year Single-center Experience With 105 Consecutive Children. Urology 2008; 84 (4): 911–918. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2014.03.059.

- Boswell TC, Hollatz P, Hutcheson JC, Vandersteen DR, Reinberg YE. Device outcomes in pediatric sacral neuromodulation: A single center series of 187 patients. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (1): 72.e1–72.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.10.010.

- BOWER WF, MOORE KH, ADAMS RD. A Pilot Study Of The Home Application Of Transcutaneous Neuromodulation In Children With Urgency Or Urge Incontinence. J Urol 2001; 166: 2420–2422. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200112000-00112.

- Lordelo P, Teles A, Veiga ML, Correia LC, Barroso U Jr. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation in children with overactive bladder: a randomized clinical trial. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2010; 184: 683–689, DOI: 10.3410/f.4324972.4410069.

- HOEBEKE P, RENSON C, PETILLON L, WALLE JVANDE, DE PAEPE H. Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation in Children With Therapy Resistant Nonneuropathic Bladder Sphincter Dysfunction: A Pilot Study. J Urol 2002; 168: 2605–2608. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200212000-00085.

- CHASE JANET, ROBERTSON VALJ, SOUTHWELL BRIDGET, HUTSON JOHN, GIBB SUSIE. Pilot study using transcutaneous electrical stimulation (interferential current) to treat chronic treatment-resistant constipation and soiling in children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 20 (7): 1054–1061. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2005.03863.x.

- BALKEN MICHAELR van, VERGUNST HENK, BEMELMANS BARTLH. The Use Of Electrical Devices For The Treatment Of Bladder Dysfunction: A Review Of Methods. J Urol 2004; 172 (3): 846–851. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000134418.21959.98.

- Capitanucci ML, Camanni D, Demelas F, Mosiello G, Zaccara A, De Gennaro M. Long-Term Efficacy of Percutaneous Tibial Nerve Stimulation for Different Types of Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction in Children. J Urol 2009; 182 (4s): 2056–2061. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.03.007.

- Barroso U, Viterbo W, Bittencourt J, Farias T, Lordêlo P. Posterior Tibial Nerve Stimulation vs Parasacral Transcutaneous Neuromodulation for Overactive Bladder in Children. J Urol 2013; 190 (2): 673–677. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.02.034.

- Jafarov R, Ceyhan E, Kahraman O, Ceylan T, Dikmen ZG, Tekgul S, et al.. Efficacy of transcutaneous posterior tibial nerve stimulation in children with functional voiding disorders. Neurourol Urodyn 2021; 40 (1): 404–411. DOI: 10.1002/nau.24575.

- Austin PF, Franco I, Dobremez E, Kroll P, Titanji W, Geib T, et al.. OnabotulinumtoxinA for the treatment of neurogenic detrusor overactivity in children. Neurourol Urodyn 2021; 40 (1): 493–501. DOI: 10.1002/nau.24588.

- Hoebeke P, De Caestecker K, Vande Walle J, Dehoorne J, Raes A, Verleyen P, et al.. The Effect of Botulinum-A Toxin in Incontinent Children With Therapy Resistant Overactive Detrusor. J Urol 2006; 176 (1): 328–331. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(06)00301-6.

- Lahdes-Vasama TT, Anttila A, Wahl E, Taskinen S. Urodynamic assessment of children treated with botulinum toxin A injections for urge incontinence: a pilot study. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2011; 45 (6): 397–400. DOI: 10.3109/00365599.2011.590997.

- Marte A, Borrelli M, Sabatino MD, Balzo BD, Prezioso M, Pintozzi L, et al.. Effectiveness of Botulinum-A Toxin for the Treatment of Refractory Overactive Bladder in Children. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2010; 20 (03): 153–157. DOI: 10.1055/s-0029-1246193.

- Chase J, Austin P, Hoebeke P, McKenna P, International Children’s Continence S. The Management of Dysfunctional Voiding in Children: A Report From the Standardisation Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. J Urol 2010; 183 (4): 1296–1302. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.12.059.

- Clothier JC, Wright AJ. Dysfunctional voiding: the importance of non-invasive urodynamics in diagnosis and treatment. Pediatr Nephrol 2018; 33 (3): 381–394. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-017-3679-3.

- PALMER LANES, FRANCO ISRAEL, ROTARIO PAUL, REDA EDWARDF, FRIEDMAN STEVENC, KOLLIGIAN MARKE, et al.. Biofeedback Therapy Expedites the Resolution of Reflux In Older Children. J Urol 2002; 168: 1699–1703. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210020-00010.

- Resnick NM, Perera S, Tadic S, Organist L, Riley MA, Schaefer W, et al.. What Predicts and what Mediates the response of urge urinary incontinence to biofeedback? Neurourol Urodyn 2013; 32 (5): 408–415. DOI: 10.1002/nau.22347.

- Kibar Y, Demir E, Irkilata C, Ors O, Gok F, Dayanc M. Effect of Biofeedback Treatment on Spinning Top Urethra in Children with Voiding Dysfunction. Urology 2007; 70 (4): 781–784. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.04.054.

- Kibar Y, Ors O, Demir E, Kalman S, Sakallioglu O, Dayanc M. Results of Biofeedback Treatment on Reflux Resolution Rates in Children with Dysfunctional Voiding and Vesicoureteral Reflux. Urology 2007; 70 (3): 563–566. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2007.03.085.

- Bauer SB, Vasquez E, Cendron M, Wakamatsu MM, Chow JS. Pelvic floor laxity: A not so rare but unrecognized form of daytime urinary incontinence in peripubertal and adolescent girls. J Pediatr Urol 2018; 14 (6): 544.e1–544.e7. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.04.030.

- Dobrowolska-Glazar BA, Groen LA, Nieuwhof-Leppink AJ, Klijn AJ, Jong TPVM de, Chrzan R. Open and Laparoscopic Colposuspension in Girls with Refractory Urinary Incontinence. Front Pediatr 2017; 5: 284, DOI: 10.3389/fped.2017.00284.

- Colposuspension in girls: clinical and urodynamic aspects. J Pediatr Urol 2005; 1 (2): 69–74. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2004.11.011.

Última actualización: 2023-02-22 15:40