54: Urethral Injury

This chapter will take approximately 7 minutes to read.

Introduction

Urethral traumas are part of the urological emergency conditions that often require multidisciplinary co-assessment. In the case of septic symptoms, all possible traumas in other organs and sources of infection should also be considered. In the case of acute symptoms of the scrotum or gross hematuria, immediate urological evaluation is required. The therapy depends on the severity of the injury; the options range from primary splinting using a catheter, possibly under visual control, to an end-to-end surgical anastomosis.

Urethral injuries are mostly caused by traffic accidents. In principle, the trauma mechanism can be classified as blunt or penetrating. In addition, urethral injuries after iatrogenic interventions (catheterization, cystoscopy, etc.) or due to foreign bodies being introduced into the urethral lumen. In addition, iatrogenic injuries are much more common in children due to their more fragile and vulnerable urethra. As a result, transurethral instruments should only be performed by experienced urologists, and endoscopic stone treatment should not be extracted primarily, but if possible, lithotripsed in situ before extraction.

Different degrees of injury to a urethral lesion is defined:

- Mild laceration with preservation of epithelial continuity

- Partial tear of the urethral epithelium

- Complete avulsion of the urethra

Evaluation

The physical examination often reveals a perineal tenderness and hematoma.

Blood on/from the urethral meatus, difficulty/inability to micturate, rapidly increasing perineal/perianal hematoma or urinoma, penile swelling after injury to the Buck fascia must indicate the presence of a urethral lesion.

The patient can complain of gross hematuria and a possible difficult micturition up to urinary retention. However, the severity of the injury cannot be assessed from the hematuria.

The rupture of the proximal urethra (above the sphincter) with subsequent urinary retention is often seen in the context of a pelvic ring fracture near the symphysis.

Hematuria

Gross hematuria is a possible sign of urethral and bladder injuries. In extreme cases, increased clot formation (urinary bladder tamponade) with possible urinary retention may occur. In the event of excessive bleeding, hemorrhagic shock can also occur. Myoglobinuria, rifampicin therapy or the consumption of particular foods such as beetroot or blueberries can also cause urine discoloration and must be taken into account in the anamnesis. The most common source of bleeding is in the urinary bladder or prostate, less often ıs the urethra or from the upper urinary tract. The urine is constantly red in total gross hematuria from the bladder or the upper urinary tract. Any accompanying symptoms such as dysuria indicate an inflammatory cause.

Urethral bleeding after accidentally pulling a urinary catheter is also possible. Usually, the injuries are minor, but the bleeding can appear very pronounced. The re-installation of a large-lumen urinary catheter for a few days is the treatment option of choice. The pressure generated on the urethral lesion usually leads to a rapid cessation of the bleeding.

If the hematuria is accompanied by proteinuria or microscopically deformed erythrocytes, a nephrologist should urgently evaluate a glomerular pathology.

In the case of painless hematuria, a prompt urological evaluation with cystoscopy and, if necessary, CT urography to rule out a malignant tumor of the urinary tract should be recommended.

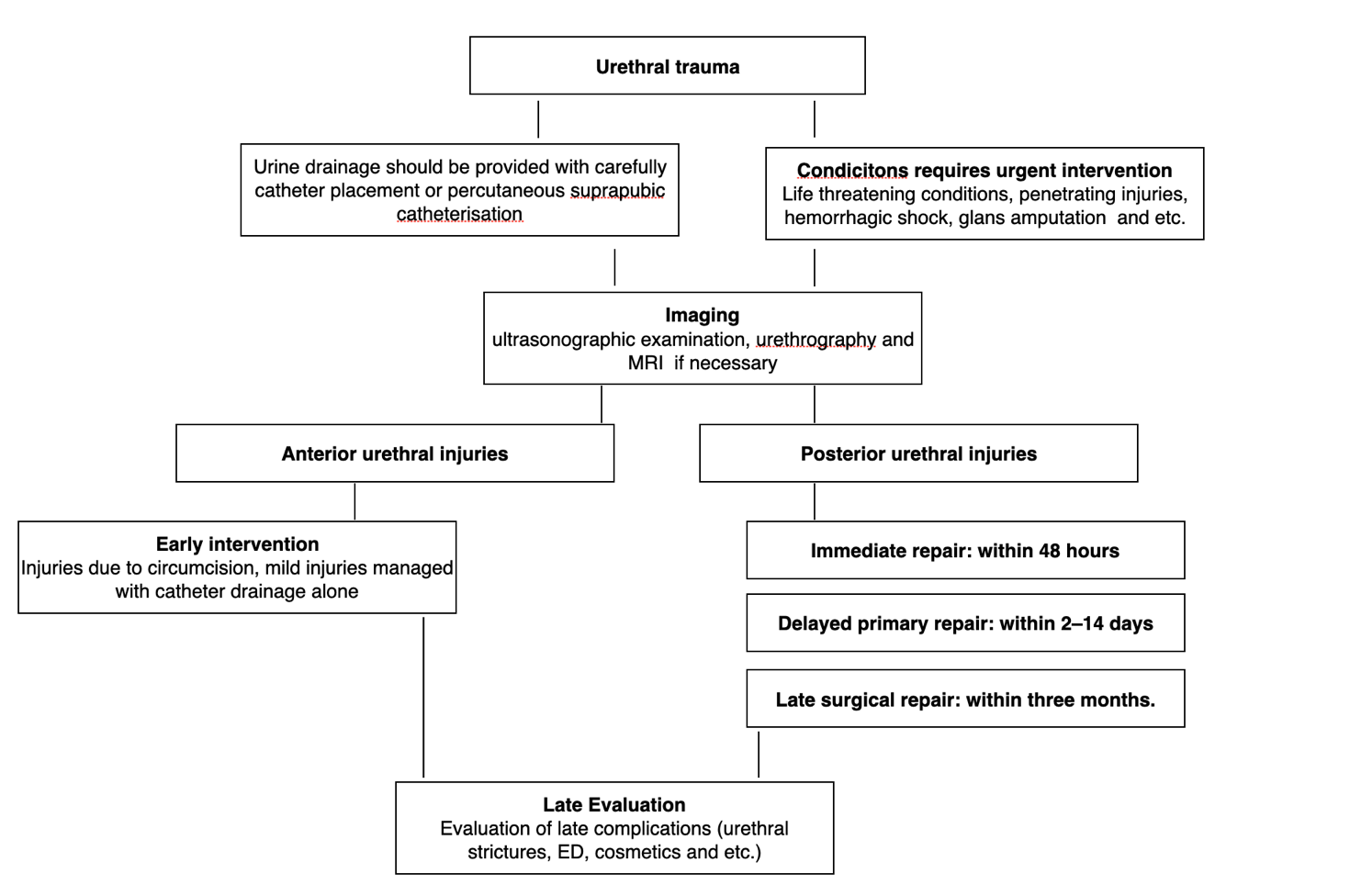

Imaging

A sonographic examination of the bladder is helpful. In the case of a full urinary bladder, relief with a suprapubic catheter is preferred. Also, carefully inserting a transurethral catheter, supported by a retrograde urethrocystography, helps assess the location of the injury. Retrograde urethrography is a gold standard for diagnosing urethral traumas, especially in boys. Endoscopically, the urethra can be realigned using a transurethral catheter inserted over a wire.

Urethral injuries in girls usually present as a partial tear in the anterior wall, rarely as a complete tear in the proximal or distal urethra. In cases of suspicion, urethrocystoscopy is indicated for evaluation.

Management

Since urethral trauma is not a life-threatening injury, it does not become the top priority in emergency management. However, it is essential to consider that this type of injury determines the patient's quality of life in the long term. Such an injury is associated with high rates of stenosis, recurrent urinary tract infections, multiple reoperations, impotence, and incontinence.

Prompt information about possible complications and risks should be provided: the more proximal the urethral injury, the higher the risk of incontinence, impotence, and stricture formation over the long term.

If urethral injuries are suspected, the catheter should not be inserted without prior specialist urological assessment. Urine drainage should be provided, and preventing infections is essential to accelerate the healing process.

Urethral injuries in children differ from adult patients because they have an immature pelvis, and the bladder is located relatively more intra-abdominal.

When a pelvic fracture occurs, the fracture becomes more unsteady. A complete posterior urethral avulsion is more common than in adults. The coexistence of bladder and urethral injuries in children is seen at about 20% traumas, and anterior longitudinal tears are detected twice as often. Prepubertal girls are four times more likely to have a urethral injury with pelvic fractures than an adult woman. The incidence of anterior urethral injury in children is less than posterior urethral injury.

Female Urethral Injuries

Minor straddle injuries to the urethra or vagina can occasionally result in substantial perineal bleeding. External and endoscopic examinations under anesthesia, suture closure of lacerations, and catheter drainage if necessary are the best management options.

Significant injuries are usually related to severe trauma and pelvic fracture and can result in longitudinal trauma to the bladder neck and urethra or total urethral dehiscence by bone fragments. In the case of difficulty in catheter placement, patients should undergo prompt cystoscopy, vaginoscopy, and rectum examination.

Stable patients should promptly have urethroplasty with urethral realignment, bladder neck repair, and vaginal laceration repair, as well as a diverting colostomy if a rectal injury occurs.

Male Urethral Injuries

Male Anterior Urethral Injuries

Circumcision complications are among the leading male distal urethral injuries. Circumcisions can result in significant urethral damage, progress to urethrocutaneous fistulas, and urethral stenosis. In contrast, meatal stenosis can occur due to routine circumcision.

Amputation of the glans is a potentially morbid complication of circumcision. Circumcision clamp methods, such as the Gomco and Plastibell clamps, have gained popularity due to their convenience. Such injuries are assumed to be the consequence of the incomplete release of the balano-preputial adhesions around the frenulum. Surgeons should verify that the mucosa has been completely released from the glans before inserting a circumcision clamp to avoid this issue.

If instant reimplantation is impossible or the amputated issue is unavailable, repair using buccal mucosa grafts should be performed after the initial injury heals.

Bulbar urethral injuries can often be managed with catheter drainage alone or with observation in the case of a minor injury. Retrograde urethrograms and endoscopies are not essential unless there is considerable urethral bleeding or a history of unsuccessful instrumentation efforts with blood at the meatus. Despite early management, late urethral strictures can occur. Endoscopic incisions could be used to manage these strictures if they are very short.

Male Posterior Urethral Injuries

Posterior urethral injuries are commonly associated with blunt trauma and pelvic fractures.

Due to a lack of large series in children, male posterior urethral injuries remain controversial regarding the appropriate timing and approach for repair. Broad-spectrum antibiotics and optimal urine drainage are essential for whatever surgical method is chosen.

According to several authors, three points in time for surgical intervention are described below:

- immediate repair: within 48 hours,

- delayed primary repair: within 2–14 days,

- late surgical repair: within three months.

Primary anastomosis is recommended only in combination with a bladder neck or rectal injury, as it has been associated with late high incontinence rates and erectile dysfunction.

The majority of posterior urethral defects are short and may be repaired with perineal anastomosis. Initially, lengthy strictures were repaired in two stages; even so, as the field of urethral reconstruction has progressed, a paradigm shift toward one-stage repair has occurred, using free and pedicle-based grafts of the skin or buccal mucosa, or a combination of these methods.

Summary

Urethral traumas in children are uncommon and require multidisciplinary co-assessment to ensure the best possible management and avoid complications and long-term comorbidities. Management principles are noted in the Key Points section below.

Key Points

- Penetrating injuries caused by external trauma should be managed surgically promptly.

- Retrograde urethrography is essential for diagnosing urethral traumas.

- Urine drainage should be provided, and preventing infections is essential to accelerate the healing process.

- Initial suprapubic cystostomy is recommended for major urethral injuries.

- Circumcision complications are among the leading male iatrogenic distal urethral injuries.

- Primary realignment may be performed in stable patients with short defects.

- The treatment of choices for posterior urethral distraction injuries are posterior urethroplasty with primary and staged anastomosis.

- The goal of therapy should be to prevent secondary complications such as urethral stricture, incontinence, urethrocutaneous fistula, periurethral diverticula, and impotence.

Figure 1 Evaluation and management of urethral injuries.

References

- Chapple CR. Urethral injury. BJU Int 2000; 86 (3): 318–326. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00101.x.

- Pippi Salle JL, Jesus LE, Lorenzo AJ, Romão RLP, Figueroa VH, Bägli DJ, et al.. Glans amputation during routine neonatal circumcision: Mechanism of injury and strategy for prevention. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (6): 763–768. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.09.012.

- Baskin LS, Canning DA, Snyder HM, Duckett JW. Surgical Repair Of Urethral Circumcision Injuries. J Urol 1997; 158 (6): 2269–2271. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68233-8.

- Weiss HA, Larke N, Halperin D, Schenker I. Complications of circumcision in male neonates, infants and children: a systematic review. BMC Urol 2010; 10 (1). DOI: 10.1186/1471-2490-10-2.

- PARK SANGTAE, McANINCH JACKW. Straddle Injuries to the Bulbar Urethra: Management and Outcomes in 78 Patients. J Urol 2004; 171 (2): 722–725. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000108894.09050.c0.

- MD AFM, F.A.C.S., MD JS. Genital and Lower Urinary Tract Trauma. Campbell-Walsh Urology 2012 (Edition , 133): 2507–2520.e5. DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4160-6911-9.00088-8.

- Morey AF, Broghammer JA, Hollowell CMP, McKibben MJ, Souter L. Urotrauma Guideline 2020: AUA Guideline. J Urol 2014; 205 (1): 30–35. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001408.

- BLANDY JP, SINGH MANMEET. The Technique and Results of One-stage Island Patch Urethroplasty. Br J Urol 1976; 47 (1): 83–87. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1975.tb03922.x.

- Chapple C, Barbagli G, Jordan G, Mundy AR, Rodrigues-Netto N, Pansadoro V, et al.. Consensus statement on urethral trauma. BJU Int 2004; 93 (9): 1195–1202. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04805.x.

Last updated: 2023-02-22 15:40