44: Testicular and Paratesticular Tumors in Children

This chapter will take approximately 20 minutes to read.

Introduction

Testicular and paratesticular tumours are uncommon in children. They can be primary or secondary, benign or malignant. This chapter gives an overview of the range of lesions clinically encountered in children. Intratesticular lesions are considered, for clinical relevance, in two pediatric age groupings:

- The prepubertal child

- The adolescent and young adult (AYA)

In either of these age groups, testicular tumors have characteristic features to consider, impacting on management and outcome. Testicular sparing surgery (TSS) can be planned for most of the benign prepubertal testicular lesions; whereas most AYA tumors are suspected to be malignant from the outset, and radical orchidectomy is standard surgical care for primary intratesticular or paratesticular malignancy.

Embryology

The fetal testis develops from the undifferentiated mesodermal gonad after 6 weeks. In a male fetus, the Müllerian duct regresses in response to AMH secreted by the developing testis. The Wolffian system develops in response to testosterone secreted by the developing testis. Leydig cells producing testosterone arise from the gonadal mesoderm and are found in the interstitium of the mature testis. The mesodermal stromal sex cords develop into seminiferous tubules and supporting epithelial cells give rise to Sertoli cells. The somatic cells of the testis are derived from the mesoderm of the gonadal ridge, but the primordial germ cells originate from the epiblast/yolk sac after around 8 days of embryonal development, and migrate to the gonadal ridge, settling in close proximity to the gonadal mesoderm.1

This derivation of cells from different embryological origins within the developing testis underlies the myriad of possible tumors, with differing behaviours, that may present in the pediatric testis.

Epidemiology

Testicular tumors in children account for 1-2% of all solid pediatric tumors.2 The incidence is estimated at 0.5-2 per 100,000 children.3 In the pediatric age group, there is a peak incidence in adolescence, with a smaller peak under 3 years of age.4

It is now very clear that most intra-testicular tumors in prepubertal children are benign. 60-70% of prepubertal intratesticular tumors are reported to be benign.5,6 75% of intratesticular tumors in post-pubertal AYA are malignant.7 The commonest benign tumor in the prepubertal age group is teratoma, presenting at a median age of 13 months.8 Yolk-sac tumours are the commonest malignant testicular tumor in the prepubertal age group, with a median age of presentation around 16 months.9 These two germ cell origin tumors form a big proportion of the early under-age-3 peak in incidence of testicular tumors.

The commonest testicular malignancy in the AYA group is mixed germ cell tumors.10 Pure seminoma is rare in AYA. Unlike prepubertal children, who predominantly get pure yolk cell tumors, the germ cell tumors in AYA are non-seminomatous and generally of mixed histology, including embryonal carcinoma as the most common histological subtype.10 Teratoma presenting in AYA is usually malignant, unlike in prepubertal children.7

Pathogenesis and Overview of Testicular and Paratesticular Tumor Types in Children

Primary testicular tumors can arise from germ cells (Germ cell tumors, GCTs) or stromal cells (Sex cord/Stromal cell tumors) of the testis. GCTs are far more common than stromal tumors .

GCTs are classified as per the World Health Organisation 2016 classification - either Germ cell neoplasia in situ derived (GCNIS-derived), which are mostly postpubertal in presentation; or not Germ cell neoplasia in situ derived (not GCNIS-derived), which mostly present in the prepubertal period.11

The not GCNIS-derived group of GCTs includes prepubertal yolk-sac tumors, prepubertal type teratoma including dermoid and epidermoid cysts, and spermatocytic tumour (which occurs mainly in adults). Carcinoma in situ or intratubular germ cell neoplasia is almost non-existent in the pre-pubertal age group, unlike in AYA and older adults.12,13

The GCNIS-derived group of GCTs includes postpubertal-type teratoma, yolk sac tumor, embryonal carcinoma, trophoblastic tumors including choriocarcinoma, all of which can present in the AYA group; and seminoma, which is more common in older adults.

Sex cord and stromal testicular tumors are rare in children. Leydig cell tumors are almost always benign in prepubertal children.14,15 Juvenile granulosa cell tumors are usually benign in the prepubertal group.16 Sertoli cell tumors are mostly benign but can be malignant in around 10%, especially in older children.17 Sertoli cell tumors may be associated with syndromes such as Carney Syndrome and Peutz-Jeghers syndrome.

Gonadoblastoma is a unique malignancy of the gonad in childhood. Gonadoblastoma cells encompass both stromal and germ cells of the gonad. Gonadoblastoma almost always presents in the context of differences or variances of sex development.18

Rare developmental anomalies of the testis such rete dysplasia of the testis can present as a mass of the prepubertal testis. Rete dysplasia is almost always associated with ipsilateral renal agenesis.19 Simple testicular cysts and epididymal cysts can also present in childhood as testicular or scrotal masses.

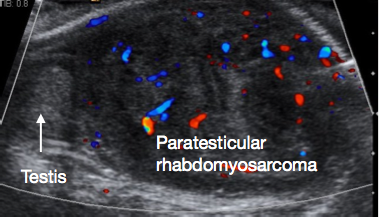

Paratesticular tumors in childhood can be benign or malignant. Benign paratesticular tumors are rare include lesions such as hemangioma, leiomyoma and lipoma.2 Malignant paratesticular tumors include rhabdomysarcoma, which is the commonest paratesticular malignancy in children.2 and the rare melanotic neuroectodermal tumour of infancy, which is mostly benign, but can exhibit malignant behaviour.20

It must be remembered that the testis in childhood is a common location for metastatic or infiltrative malignancy, such as metastatic leukemia or lymphoma.7

Whilst cryptorchidism is a known risk factor for testicular malignancy, majority of reported childhood testicular tumors are not associated with cryptorchidism. Cryptorchidism is associated with an increased risk of post-pubertal malignancy, bilaterally, by 2-5 times that of the general population.21 This risk appears to be reduced by orchidopexy early in childhood.22 Malignancy type occurring most commonly in uncorrected or late-operated cryptorchidism is seminoma.23

Testicular microlithiasis, usually incidentally detected on ultrasound scan in children, has not been shown to be associated with an increased risk of childhood testicular tumors . Testicular microlithiasis may be associated with an increased risk of testicular malignancy in adult life, especially if associated with other risk factors such as cryptorchidism. Postpubertal testicular self examination is thus advised to facilitate early detection.24

Evaluation and diagnosis

The commonest mode of presentation of testicular or paratesticular tumor is a painless scrotal mass, noted by the child or carer. Sometimes, a reactive hydrocele may be present. Scrotal swelling may herald review and investigation, and occasionally the mass may be detected incidentally after presentation with trauma, or on ultrasound scan (USS). There may be few other discerning clinical characteristics noted if a scrotal lump is palpated. However, Leydig cell tumors may be associated with signs of precocious puberty, and 10% of Sertoli cell tumors may also present with signs of precocious puberty.25

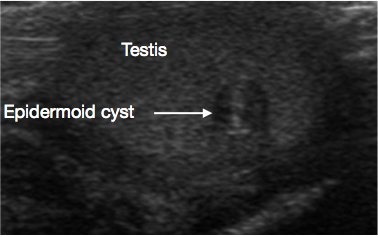

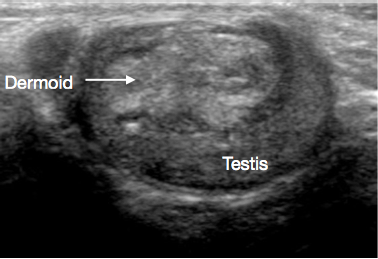

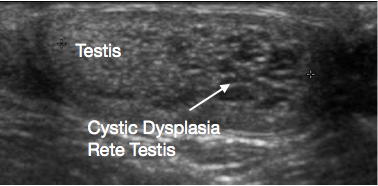

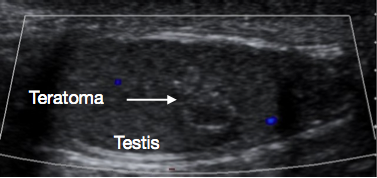

USS of the scrotum and testis is a very useful initial investigation. It usually provides a clear indication of location and size of mass, whether solid or cystic, whether diffuse or well defined, whether intratesticular or paratesticular, its vascularity and whether uni or multifocal. Some prepubertal lesions have characteristic features on USS, such as the ‘onion peel’ layers of an epidermal cyst (Figure 1), lobulated appearance of dermoid cyst (Figure 2), and characteristic cystic appearance of rete dysplasia of the testis (Figure 3).26 Teratomas may have a variegated cystic/solid appearance (Figure 4). Benign lesions tend to display low vascularity on USS. Malignant lesions are usually hypoechoic, solid and homogenous on USS.

Figure 1 Ultrasound of Testicular epidermoid cyst, onion peel appearance (Arrow)

Figure 2 Ultrasound of Testicular dermoid cyst, lobulated cyst filled with debris

Figure 3 Ultrasound of Cystic dysplasia rete testis, testis on left and cystic dysplasia on right of image

Figure 4 Ultrasound of Prepubertal testicular teratoma, variegated appearance

Serum tumor markers may be helpful in discerning benign from malignant lesions. For testicular tumours, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (BHCG) and Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) are the most commonly used markers. BHCG is usually not useful in prepubertal tumor evaluation as choriocarcinoma and embryonal carcinoma, which may secrete BHCG, are almost never noted in this age group.7,27 However, BHCG is very important in the post-pubertal AYA group, where these lesions can occur. AFP is the most important marker in the prepubertal age group, as it is markedly raised in almost all yolk cell tumors, commonly seen in this age group.9 Teratoma may have a mildly elevated AFP, but AFP levels over 100ng/mL have not been reported in prepubertal teratoma.9 This marked difference in AFP levels between benign teratoma and malignant yolk cell tumor also helps in planning for TSS versus radical orchidectomy. It should be noted whilst interpreting AFP levels, that infants up to 8 months of age may have naturally high serum AFP levels.28

Clinical characteristics, imaging characteristics of the lesion, and serum tumor marker levels will help guide further management. If the lesion is suspected to be malignant, staging abdominal pelvic and chest CT to assess for locoregional spread and metastases would be important. 20% of prepubertal yolk cell tumors have lung metastases at presentation.29

A lesion with clinical and USS characteristics of a benign tumor, and with no elevation in tumor marker serum levels, does not usually require staging CT prior to resection.

Summary of Testicular Tumors in Prepubertal Children

Table 1 Testicular and Paratesticular Tumors in Childhood

| Classification | Type | Subtype | Benign | Mostly benign, may be malignant | Malignant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Testicular/Gonadal tumors | Prepubertal Testicular Tumors | GCT - not GCNIS derived | Prepubertal Teratoma | Yolk sac tumor | |

| Epidermoid cyst | |||||

| Dermoid cyst | |||||

| Sex Cord / Stromal Tumors | Juvenile granulosa cell tumor | Leydig cell tumor | |||

| Sertoli cell tumor | |||||

| Developmental Anomalies and Simple Cysts | Cystic Dyplasia Rete Testis | ||||

| Testicular cyst | |||||

| Epididymal cyst | |||||

| Testicular Tumors in Adolescents and Young Adults (AYA) | GCT - GCNIS derived | Postpubertal Teratoma | |||

| Embryonal carcinoma | |||||

| Yolk cell tumor | |||||

| Choriocarcinoma | |||||

| Mixed GCTs | |||||

| Seminoma | |||||

| Gonadal tumor in Differences of Sex Development (DSD) | Gonadoblastoma | ||||

| Secondary Testicular metastases/infiltration | Leukemia e.g., acute lymphoblastic leukemia | ||||

| Lymphoma e.g., Burkitts Lymphoma | |||||

| Paratesticular Tumors | Hemangioma | Melanotic Neuroectodermal Tumor of Infancy | Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma | ||

| Leiomyoma | |||||

| Lipoma | |||||

GCT=Germ cell tumor, GCNIS=Germ cell neoplasia in situ

Primary Testicular/ Gonadal Tumors

Testicular Benign GCTs (not GCNIS derived)

Teratoma

These are almost always benign when presenting prepubertally.8 Median age of presentation is 13 months.2 They often have a heterogenous appearance on USS (Figure 4) because teratomas can have elements from any or all of the three embryonal germ cell layers - endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. Teratomas usually contain mature elements in this age group, with immature elements occasionally reported. Even with immature elements, outcome after TSS is usually good in this age group.30 TSS is usually feasible for prepubertal teratoma, and after successful excision and histological confirmation of benign nature, usually no further follow up is required.27

Epidermoid cyst

These are benign cysts of ectodermal origin, lined by epithelium that produces keratin. The cyst has a characteristic layered ‘onion-peel’ appearance on USS (Figure 1).11 They are easily enucleated, so TSS is standard of care. Routine long-term surveillance is not required post-excision, but rare recurrence is reported.26

Dermoid cyst

Dermoid cysts comprise cutaneous-type elements, including appendages such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands. They are benign. USS appearances often show thick walled, smooth contoured cystic lesions with avascular echogenic debris (Figure 2).31,32 TSS is standard of care, and routine surveillance post excision is not usually required.27

Testicular Malignant GCTs (not GCNIS derived)

Yolk cell tumor

This is the commonest intratesticular malignancy in the prepubertal child.The usual age of presentation is in the early peak under age 3, at median 16 months of age.9 The tumors are usually solid and homogenous usually on USS. Serum AFP is markedly elevated. 80% of prepubertal yolk cell tumors are stage 1 at presentation.33 20% have lung metastases at presentation.2 If a yolk sac tumor is suspected, staging CT chest, abdomen and pelvis should be performed, and radical orchidectomy planned. Radical lymph node dissection (RLND) is not routinely performed for prepubertal yolk cell tumor, as hematogenous spread without locoregional spread is common in yolk cell tumor; which RLND, with its significant risk of morbidity, will not address.34

For confirmed Stage 1 disease, with normalisation of serum AFP post surgery, chemotherapy is usually not required. Recurrence rates are around 20% . Regular post-surgical oncological surveillance with AFP level screening plus imaging such as MRI is thus advised, and salvage rates after treatment of recurrence are excellent.2,35 For clinical stage 2 disease with lymph node involvement, and metatstatic disease, chemotherapy is indicated in most protocols. Platinum-based chemotherapy is highly effective for yolk sac tumor. RLND is reserved for locoregional residual or recurrent disease.2,33

Testicular Sex Cord and Stromal tumors

Juvenile Granulosa cell tumors

These usually benign tumors usually occur in infants, and are the most common neonatal testicular tumors. Histologically, they are comprised of sheets of granulosa like cells, often with cystic change.16,36 TSS is usually successful and curative, recurrences have not been reported, and long-term surveillance after excision is not usually required.27

Leydig cell tumors

In children Leydig cell tumors are usually benign, although they can be malignant in adults. Leydig cell tumors usually present in children of around 5-10 years of age.14,15 Most present as a painless testicular mass. However, Leydig cell tumors can present with precocious puberty due to testosterone production . In addition, 10-15% of children with Leydig cell tumors can have signs of feminisation such as gynaecomastia due to estradiol secretion.2 The intraoperative appearance of Leydig cell tumors is of yellow homogenous nodules. In prepubertal children, TSS is recommended as Leydig cell tumors are almost always benign in this age group. If precocious puberty is an associated feature, then endocrinology review and follow up is advised. Pubertal changes do not reverse after the tumor is excised, as the pubertal hormonal axis has been activated.2

Sertoli cell tumors

These present at a young median age of 6 months, although they can occur at any prepubertal age. A third are associated with syndromes such as Peutz-Jeghers or Carney syndrome. 10% present with changes of precocious puberty because they are hormonally active; or even gynaecomastia, due to tumor secretion of aromatase, resulting in conversion of androstenedione to estrone.37 They are mostly benign, but can be malignant in older children. Hence, pre-operative staging CT would be prudent, especially in children over age 5 years. Current guidelines recommend considering TSS for Sertoli cell tumors in children.27

Developmental anomalies and cysts

Cystic dysplasia of the rete testis is a rare developmental anomaly that presents as a testicular lump. It is almost always associated with ipsilateral renal agenesis. USS shows the lesion to be cystic, usually at the upper pole of testis, with compression of adjacent normal testicular tissue (Figure 3). Traditionally TSS for the lesion was recommended. Significant rates of recurrence after TSS have been reported. With the characteristic appearance on ultrasound and associated ipsilateral renal anomaly, its benign nature, and increasing reports of regression of the lesion over time, conservative testicular-sparing management with surveillance is now being suggested. A biopsy of the lesion, if there is any doubt about the diagnosis prior to conservative management, may be considered.38,39

Simple epididymal cysts and intratesticular cysts may occur in childhood. Occasionally they are symptomatic. They are usually amenable to enucleation or deroofing if required.

Summary of Testicular Tumors in AYA

Testicular tumors in AYA are usually malignant, and usually GCTs, mainly GCNIS-derived. Testicular GCTs comprise 14% of adolescent malignancies, and are the commonest solid tumor in this age bracket .

Histologically, they mostly tend to be embryonal carcinomas, with mixed non-seminomatous GCT components. They often present with metastatic disease and have a higher rate of relapse. Assessment of suspected malignancies includes imaging with USS, tumour markers - AFP, BHCG and LDH, and staging CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis.10 Postpubertal teratoma is also GCNIS derived unlike its prepubertal counterpart. Metastases occur in 22-37% of AYA teratoma.40 It should also be noted that malignant testicular tumours in AYA may not necessarily have elevated tumor markers.41

Standard of care for a suspected testicular malignancy in AYA is radical orchidectomy by inguinal approach. For localised disease, radical orchidectomy is usually curative. AYAs who have clinical stage 1 disease after orchidectomy, usually undergo active surveillance for detection of recurrence; 20-30% will have clinical recurrence, and survival with salvage chemotherapy is excellent.10 This conservative approach limits over-treatment of majority with clinical stage 1 disease, and limits exposure to platinum based chemotherapy side effects, by targeting the treatment to those who have demonstrable recurrent disease. Tumors >4cm, lymphovascular invasion, and an increasing component of embryonal carcinoma are associated with a higher risk of metastatic disease.42

AYAs with clinical stage II and III disease usually receive chemotherapy. RLND is selectively used for those with residual disease or mass post chemotherapy, despite tumor markers being negative, as the residual lesion may be teratoma, usually less responsive to chemotherapy.10

Summary of Paratesticular Tumors in Children

TSS with focal excision of the lesion is usually considered for rare benign paratesticular lesions such as lipoma.

Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of infancy is a rare tumor affecting the epididymal and paratesticular region.20 It is usually benign, but histologically differentiating it from round blue cell malignancies on biopsy can be a challenge. Typically benign, orchidectomy is usually curative; but 10% can display malignant behaviour with recurrence and/or metastases. After surgery, follow up surveillance with cross sectional imaging such as MRI is advised.2

Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma is the most commonly encountered paratesticular malignancy in childhood. It comprises 5% of all intrascrotal malignancies, and 40% of all paratesticular malignancies.43 There is a bimodal peak in incidence, one in the AYA group and one in infants under 6 months of age. The tumor originates from the mesenchymal elements of paratesticular tissues. Presentation is usually with a painless scrotal mass, and a significant proportion have metastatic disease at presentation. USS usually shows a solid paratesticular lesion (Figure 5). Staging abdominal, pelvis and chest CT is required to assess for locoregional and metastatic spread. Tumour markers are usually negative.

Figure 5 Ultrasound of Paratesticular Rhabdomyosarcoma, normal testis on left of image, large paratesticular mass on right of image

A consensus statement from the Children’s Oncology Group (COG), the European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group (EpSSG) and the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe (CWS) about surgical management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma has been recently published.44 Radical orchidectomy with en-bloc resection of the tumor, testis and cord to the internal ring, is current recommended surgical management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma. Scrotal approach for resection is contraindicated as it makes proximal clearance at the level of the internal ring difficult; trans-scrotal biopsy should also be avoided as it increases risk of tumor spill.

Most paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma in childhood are histologically embryonal. If the lesion is embryonal, then for children over age 10 years, retroperitoneal lymph node evaluation is advised for any clinical stage; but for boys under age 10 years, retroperitoneal lymph node evaluation is performed only if there is evidence of local spread or enlarged nodes. If there are enlarged nodes on imaging and no lymph node evaluation is done, recommendation is to treat with chemotherapy as though nodes are involved.44

For histologically alvaeolar rhabdomyosarcoma, retroperitoneal lymph node evaluation is recommended for all patients regardless of imaging findings. If lymph nodes are positive, then chemotherapy and radiotherapy are indicated.44

Outcomes after paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma treatment are better for the prepubertal group than AYA group. There is a 90% failure-free survival in the prepubertal age group versus 63% in adolescents.45

Metastases or Infiltrative Malignancy in Testes in Childhood

Testes are a common site of infiltration in leukemia and lymphoma - such as acute lymphoblastic leukemia, follicular lymphoma or Burkitt’s lymphoma in children. Presentation is usually with a significantly enlarged testis unilaterally or bilaterally. Ultrasound scan findings often delineate a diffusely hypoechoic enlarged testis with hypervascularity.46

TSS and Radical Orchidectomy

Clinical guidelines now strongly recommend TSS for prepubertal testicular tumors that are strongly suspected to be benign on work-up.27 TSS is performed by inguinal approach. Atraumatic vessel clamping of the spermatic cord prior to testicular mobilisation and dissection is considered a standard oncological technique, and allows to minimise bleeding and optimise visualisation of the dissection in the usually small prepubertal organ. (Figure 6).

Figure 6 TSS - Atraumatic vascular clamp on cord, Leydig cell tumor at lower pole testis

Frozen section assessment is useful to help confirm that the lesion is benign and that margins are clear. In many experienced centres, frozen section is not routinely performed now for prepubertal tumor-marker-negative lesions with benign clinical and ultrasound characteristics.41 If there is doubt or suspicion of malignancy despite the steps of TSS, then TSS is abandoned and radical orchidectomy is performed. If TSS is successfully performed, the tunica albuginea is sutured closed after lesion resection, and the testis replaced in the scrotum.

In all children with clinically suspected testicular and paratesticular malignancy, preoperative staging for locoregional and metastatic spread should be performed. Standard of care for malignant lesions is radical orchidectomy, performed via inguinal approach and with vascular clamping prior to mobilisation of the testis and lesion. The cord should be ligated and resected at the level of the internal ring. For paratesticular lesions, the tumor should be resected en-bloc with the testis and cord; if there is scrotal skin invasion, then the affected scrotal skin should be resected en-bloc with the lesion as well.44

Clinical Staging for Malignant Tumors

The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) use a Stage I-IV clinical staging system for prepubertal testicular malignancies (Table 2). Stage I is essentially disease localised to the testis at time of resection.

Table 2 Children’s Oncology Group Staging for Testicular Tumors

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| I | Limited to testis, completely resected by high inguinal orchidectomy; no clinical, radiographic, or histologic evidence of disease beyond the testes |

| Patients with normal or unknown tumor markers at diagnosis must have a negative ipsilateral RPLND to confirm stage I disease if imaging demonstrates LNs >2 cm | |

| Patients who have undergone scrotal orchidectomy with high ligation of cord are stage I” | |

| II | “Trans-scrotal biopsy; microscopic disease in scrotum or high in spermatic cord (<5 cm from proximal end) |

| Failure of tumor markers to normalize or decrease with an appropriate half-life” | |

| III | Trans-scrotal biopsy; microscopic disease in scrotum or high in spermatic cord (<5 cm from proximal end) |

| LNs >4 cm by CT or 2–4 cm with biopsy proof” | |

| IV | Distant metastases, including liver |

| III | Retroperitoneal LN involvement, but no visceral or extra-abdominal involvement |

The American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) generally uses the Tumor (T), Nodes (N) and Metastases (M) system with an S delineation for post surgical tumor markers (Table 3).

Table 3 AJCC Staging

| T-Primary Tumor | N-Regional LNs | M-Distant Metastasis | S-Serum Tumor Markers |

|---|---|---|---|

| pT0 – no evidence of primary tumor | cN0 – no regional LN metastasis | M0 – no distant metastasis | S0 – marker levels within normal limits |

| pTis – intratubular germ cell neoplasia (carcinoma in-situ) | pN0 – no regional LN metastasis | M1 – distant metastasis | S1 - LDH < 1.5 X N and hCG (mIU/mL) <5000 and AFP (ng/mL) <1000 |

| pT1 – tumor limited to the testis and epididymis without LVI; tumor may invade into the tunica albuginea but not the tunica vaginalis | cN1 – metastasis with an LN mass≤ 2 cm or multiple LNs, none>2 cm | M1a – nonregional nodal or pulmonary metastasis | S2 LDH 1.5–10 X N or hCG (mIU/mL) 5000–50,000 or AFP (ng/mL) 1000–10,000 |

| pT2 – tumor limited to the testis and epididymis with LVI, or tumor extending through the tunica albuginea with involvement of the tunica vaginalis | pN1 – metastasis with an LN mass≤2 cm and ≤5 nodes positive, none >2 cm | M1b – distant metastasis other than to nonregional LNs and lung | S3 LDH >10 x N or hCG (mIU/mL) >50,000 or AFP (ng/mL) >10,000 |

| pT3 – tumor invades the spermatic cord with or without LVI | cN2 – metastasis with an LN mass 2–5 cm or multiple LNs, any one>2 cm but not >5 cm | ||

| pT4 –tumor invades the scrotum with or without LVI | pN2 – metastasis with an LN mass 2–5 cm, or >5 nodes positive, none >5 cm, or evidence of extranodal tumor extension | ||

| cN3 – metastasis with an LN mass >5 cm | |||

| pN3 – metastasis with an LN mass>5 cm |

AFP: alpha fetoprotein; hCG : beta human chorionic gonadotropin; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; LN: lymph node; LVI: lymphovascular invasion; N: normal; c: clinical; p: pathologic; T: primary tumor; N: regional lymph nodes; M: metastasis; S: serum tumor markers.

The now superseded Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma Studies (IRS) established both a ‘grouping’ system based on surgical resectability, and an IRS- modified TNM Staging system for paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma.

Complications of Treatment

Both TSS and radical orchidectomy are procedures associated with good recovery, with small associated risks of bleeding with scrotal haematoma, infection and lesion recurrence. Testicular atrophy is rare after TSS.41

In recent years, focus of managing pediatric testicular and paratesticular tumors has been on reducing the risks and long term negative effects of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, by stratifying tumour risk, and only offering further treatment to children who meet the required criteria. Most children with stage I disease will be offered active surveillance after tumor resection now, and only those with demonstrated recurrent disease will require chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy side effects such as cisplatin nephrotoxicity and peripheral neuropathy, and lung fibrosis after Bleomycin, are well reported.

Long term negative effects of chemo and radiotherapy include fertility impairment and secondary malignancies.

Suggested Follow Up and Surveillance After Treatment

Confirmed benign lesions with clear margins such as prepubertal teratoma do not generally require routine long term surveillance after TSS. However, clinical guidelines suggest initial post surgical follow up with ultrasound scan 3-6 monthly for the first post-operative year.27

All children with testicular and paratesticular malignancy require appropriate follow up and surveillance for a few years as per oncological protocols. This is to maintain active surveillance for recurrent disease, and to monitor for long term effects after surgery and treatment with chemotherapy and /or radiotherapy.

Key Points

- Majority of prepubertal testicular tumors are benign

- Majority of malignant prepubertal testicular tumors are pure yolk cell tumors

- Sex cord / Stromal testicular tumors are rare in childhood and largely tend to be benign

- Majority of testicular tumors in AYA are malignant

- Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma is the commonest paratesticular malignancy in children, but remains rare

Conclusions

Majority of prepubertal testicular tumors are benign. TSS is safe to consider and recommended for prepubertal testicular tumours with clinical and USS characteristics of a benign lesion, and negative tumor markers.

Majority of malignant prepubertal testicular tumors are pure yolk cell tumors. AFP is markedly elevated in most yolk cell tumors. After staging CT work-up, treatment is by radical orchidectomy. Most have Stage I disease localised to the testis and surgery is curative. Chemotherapy is reserved for children with disease Stage II or higher, or for those with Stage I who have recurrence after surgery.

Majority of testicular tumors in AYA are malignant. They tend to be embryonal carcinomas and mixed germ cell tumors.

Sex cord / Stromal testicular tumors are rare in childhood and largely tend to be benign and amenable to TSS.

Paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma is the commonest paratesticular malignancy in children. After appropriate staging and work-up, treatment is usually radical orchidectomy en-bloc with the paratesticular tumor mass, by inguinal approach. If the lesion is embryonal on histology, retroperitoneal lymph node evaluation is recommended for children older than age 10 years, regardless of stage; and for boys under 10 years old who have evidence of locoregional disease or nodal recurrence. If the lesion is alveolar on histology, retroperitoneal lymph node evaluation is recommended for all regardless of imaging findings.

References

- Silber S. Testis Development, Embryology, and Anatomy. 2018. In: Fundamentals of Male Infertility \[Internet\]. Springer; , DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-76523-5_1.

- Ahmed HU, Arya M, Muneer A, Mushtaq I, Sebire NJ. Testicular and paratesticular tumours in the prepubertal population. Lancet Oncol 2010; 11 (5): 476–483. DOI: 10.1016/s1470-2045(10)70012-7.

- Coppes MJ, Rackley R, Kay R. Primary testicular and paratesticular tumors of childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol 1994; 22 (5): 329–340. DOI: 10.1002/mpo.2950220506.

- Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Koch S, Teske C, Schmidt P, Haas RJ. Epidemiologic analysis of 1,442 children and adolescents registered in the German germ cell tumor protocols. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2004; 42 (2): 169–175. DOI: 10.1002/pbc.10321.

- Nerli RB, Ajay G, Shivangouda P, Pravin P, Reddy M, Pujar VC. Prepubertal testicular tumors: our 10 years experience. Indian J Cancer 2010; 47 (3): 292–295. DOI: 10.4103/0019-509x.64730.

- Woo LL, Ross JH. Partial orchiectomy vs. radical orchiectomy for pediatric testis tumors. Transl Androl Urol 2020; 9 (5): 2400–2407. DOI: 10.21037/tau-19-815.

- Jarvis H, Cost NG, Saltzman AF. Testicular tumors in the pediatric patient. Semin Pediatr Surg 2021; 30 (4). DOI: 10.1016/j.sempedsurg.2021.151079.

- Grady RW, Ross JH, Kay R. Epidemiological features of testicular teratoma in a prepubertal population. J Urol 1997; 158 (3 Pt 2): 1191–1192. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199709000-00129.

- Ross JH, Rybicki L, Kay R. Clinical behavior and a contemporary management algorithm for prepubertal testis tumors: a summary of the Prepubertal Testis Tumor Registry. J Urol 2002; 168 (4 Pt 2): 8–9. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210020-00004.

- Saltzman AF, Cost NG. Adolescent and Young Adult Testicular Germ Cell Tumors: Special Considerations. Adv Urol 2018; 2018 (2375176). DOI: 10.1155/2018/2375176.

- Williamson D SR, B M-G, C A, F E, L U, T.M.. The World Health Organization 2016 classification of testicular germ cell tumours: a review and update from the International Society of Urological Pathology Testis Consultation Panel. Histopathology 2017; 70: 335–346. DOI: 10.1111/his.13102.

- Renedo DE, Trainer TD. Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN) with p53 and PCNA expression and adjacent mature teratoma in an infant testis. An immunohistochemical and morphologic study with a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 1994; 18 (9): 947–952. DOI: 10.1097/00000478-199409000-00010.

- Hawkins E, Heifetz SA, Giller R, Cushing B. The prepubertal testis (prenatal and postnatal): its relationship to intratubular germ cell neoplasia: a combined Pediatric Oncology Group and Childrenś Cancer Study Group. Hum Pathol 1997; 28 (4): 404–410. DOI: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90027-7.

- Agarwal PK, Palmer JS. Testicular and paratesticular neoplasms in prepubertal males. J Urol 2006; 176 (3): 875–881. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.04.021.

- Luckie TM, Danzig M, Zhou S, Wu H, Cost NG, Karaviti L. A Multicenter Retrospective Review of Pediatric Leydig Cell Tumor of the Testis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2019; 41 (1): 74–76. DOI: 10.1097/mph.0000000000001124.

- Grogg JB, Schneider K, Bode PK, Kranzbuhler B, Eberli D, Sulser T. Risk factors and treatment outcomes of 239 patients with testicular granulosa cell tumors: a systematic review of published case series data. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2020; 146 (11): 2829–2841. DOI: 10.1007/s00432-020-03326-3.

- Talon I, Moog R, Kauffmann I, Grandadam S, Becmeur F. Sertoli cell tumor of the testis in children: reevaluation of a rarely encountered tumor. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2005; 27 (9): 491–494.

- Chung JM, Lee SD. Overview of pediatric testicular tumors in Korea. Korean J Urol 2014; 55 (12): 789–796. DOI: 10.4111/kju.2014.55.12.789.

- Ulbright TM, Young RH. Testicular and paratesticular tumors and tumor-like lesions in the first 2 decades. Semin Diagn Pathol 2014; 31 (5): 323–381. DOI: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.07.003.

- Calabrese F, Danieli D, Valente M. Melanotic neuroectodermal tumor of the epididymis in infancy: case report and review of the literature. Urology 1995; 46 (3): 415–418. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80234-9.

- Pettersson A, Richiardi L, Nordenskjold A, Kaijser M, Akre O. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med 2007; 356 (18): 1835–1841. DOI: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2007.08.002.

- Schneuer FJ, Milne E, Jamieson SE, Pereira G, Hansen M, Barker A. Association between male genital anomalies and adult male reproductive disorders: a population-based data linkage study spanning more than 40 years. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2018; 2 (10): 736–743. DOI: 10.1016/s2352-4642(18)30254-2.

- Wood HM, Elder JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: separating fact from fiction. J Urol 2009; 181 (2): 452–461. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-4071(09)79277-2.

- LAt H, NR B, C R, HS D, RJM N, J Q. The prognostic value of testicular microlithiasis as an incidental finding for the risk of testicular malignancy in children and the adult population: A systematic review. On Behalf of the EAU Pediatric Urology Guidelines Panel Epub Ahead of Print Journal of Pediatric Urology 2021. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.06.013.

- Thomas JC, Ross JH, Kay R. Stromal testis tumors in children: a report from the prepubertal testis tumor registry. J Urol 2001; 166 (6): 2338–2340. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65583-8.

- Friend J, Barker A, Khosa J, Samnakay N. Benign scrotal masses in children - some new lessons learned. J Pediatr Surg 2016; 51 (10): 1737–1742. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.07.016.

- Stein R, Quaedackers J, Bhat NR, Dogan HS, Nijman RJM, Rawashdeh YF. EAU-ESPU pediatric urology guidelines on testicular tumors in prepubertal boys. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 17 (4): 529–533. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2021.06.006.

- Wu JT, Book L, Sudar K. Serum alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal infants. Pediatr Res 1981; 15 (1): 50–52. DOI: 10.1203/00006450-198101000-00012.

- Haas RJ, Schmidt P, Gobel U, Harms D. Testicular germ cell tumors, an update. Results of the German cooperative studies 1982-1997. Klin Padiatr 1999; 211 (4): 300–304.

- A DB, GC M, R P, P H, FG H-C, JW O. Influence of tumor site and histology on long-term survival in 193 children with extracranial germ cell tumors. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2008; 18 (1): 1–6. DOI: 10.1055/s-2007-989399.

- Ulbright TM, Srigley JR. Dermoid cyst of the testis: a study of five postpubertal cases, including a pilomatrixoma-like variant, with evidence supporting its separate classification from mature testicular teratoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2001; 25 (6): 788–793.

- P GA, LM HF, M JG, C SF, D SA, S NL. \[Mature cystic teratoma of the testis (dermoid cyst. Case Report and Literature Review\] Arch Esp Urol 2009; 62 (9): 747–751.

- Grady RW. Current management of prepubertal yolk sac tumors of the testis. Urol Clin North Am 2000; 27 (3): 503–508. DOI: 10.1016/s0094-0143(05)70097-5.

- Grady RW, Ross JH, Kay R. Patterns of metastatic spread in prepubertal yolk sac tumor of the testis. J Urol 1995; 153 (4): 1259–1261. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-199504000-00068.

- Ye YL, Zheng FF, Chen D, Zhang J, Liu ZW, Qin ZK. Relapse in children with clinical stage I testicular yolk sac tumors after initial orchiectomy. Pediatr Surg Int 2019; 35 (3): 383–389. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-018-04426-5.

- Kao CS, Cornejo KM, Ulbright TM, Young RH. Juvenile granulosa cell tumors of the testis: a clinicopathologic study of 70 cases with emphasis on its wide morphologic spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol 2015; 39 (9): 1159–1169. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.07.011.

- Dursun F, Su Dur SM, Sahin C, Kirmizibekmez H, Karabulut MH, Yoruk A. A Rare Cause of Prepubertal Gynecomastia: Sertoli Cell Tumor. Case Rep Pediatr 2015; 2015 (439239). DOI: 10.1155/2015/439239.

- Gelas T, Margain Deslandes L, Mestrallet G, Pracros JP, Mouriquand P. Spontaneous regression of suspected cystic dysplasia of the rete testis in three neonates. J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (6): 1–4. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.05.032.

- Helman T, Epelman M, Ellsworth P. Cystic Dysplasia of the Rete Testis: Does Pathophysiology Guide Management? Urology 2020; 141: 150–153. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.03.026.

- Farci F, Teratoma SST. StatPearls. .

- Bois JI, Vagni RL, Badiola FI, Moldes JM, Losty PD, Lobos PA. Testis-sparing surgery for testicular tumors in children: a 20 year single center experience and systematic review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int 2021; 37 (5): 607–616. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-020-04850-6.

- Vergouwe Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Albers P, Habbema JD. Predictors of occult metastasis in clinical stage I nonseminoma: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol 2003; 21 (22): 4092–4099. DOI: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2004.02.005.

- Shapiro E, Strother D. Pediatric genitourinary rhabdomyosarcoma. J Urol 1992; 148 (6): 1761–1768. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37023-4.

- Rogers TN, Seitz G, Fuchs J, Martelli H, Dasgupta R, Routh JC. Surgical management of paratesticular rhabdomyosarcoma: A consensus opinion from the Childrenś Oncology Group, European paediatric Soft tissue sarcoma Study Group, and the Cooperative Weichteilsarkom Studiengruppe. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2021; 68 (4). DOI: 10.1002/pbc.28938.

- Crist WM, Anderson M JR, JL F, C R, RB R, F.B.. Intergroup rhabdomyosarcoma study-IV: results for patients with nonmetastatic disease. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19 (12): 3091–3102. DOI: 10.1200/jco.2001.19.12.3091.

- Sanguesa C, Veiga D, Llavador M, Serrano A. Testicular tumours in children: an approach to diagnosis and management with pathologic correlation. Insights Imaging 2020; 11 (1). DOI: 10.1186/s13244-020-00867-6.

Last updated: 2025-09-25 12:10