40: DSD—Current Understanding, Workup and Treatment

This chapter will take approximately 21 minutes to read.

Introduction and Terminology

Disorders/differences of sex development (DSD, also referred to as intersex) are congenital conditions in which chromosomal, gonadal or phenotypic sex are different from what is seen as typically male or female. A new, broad DSD classification was introduced in 2006 via the “Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders.”1 This newer classification incorporates a wide range of conditions, including congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), ovotesticular DSD, androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS). The 2006 consensus definition is more expansive than what were previously referred to as intersex conditions, also including anatomic anomalies such as cloacal and bladder exstrophy and vaginal agenesis, and chromosomal abnormalities that do not cause atypical genitalia (e.g., Klinefelter Syndrome [47, XXY]). Table 1 provides an overview of previous nomenclature, and recommended terminology updates proposed in the 2006 consensus statement. Give the wide range of conditions under the DSD ‘umbrella’, an individualized, multidisciplinary approach to care is paramount.

Table 1 Revised DSD Nomenclature. Source: Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF. Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders. Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines &Amp; Policies 2006; 118: 1317–1317. DOI: 10.1542/9781610021494-part06-consensus_statement2.

| Previous | Proposed |

|---|---|

| Intersex | DSD |

| Male pseudohermaphrodite | 46,XY DSD |

| Female pseudohermaphrodite | 46,XX DSD |

| True hermaphrodite | Ovotesticular DSD |

| Mixed gonadal dysgenesis | Mixed gonadal dysgenesis (unchanged) |

| XX male or XX sex reversal | 46,XX testicular DSD |

| XY sex reversal | 46,XY complete gonadal dysgenesis |

There has been near universal uptake of the new DSD terminology by the medical community since it was introduced. Among individuals affected by DSD conditions, variability of terminology preferences exist, and there is a lack of consensus about exactly which conditions should be considered a DSD.2,3,4 In particular, some members of the CAH community identify as having an endocrine disorder, not a DSD/intersex condition.5 It is also unclear which individuals with proximal hypospadias should be considered to have “a DSD”.6 Clinicians who care for DSD conditions should be aware of the nomenclature evolution and controversies, and use the terms that their patients prefer during individual medical encounters. For the purposes of this chapter, the current, medically accepted terminology will be utilized.

Embryology

Typical Development of Internal/External Genitalia

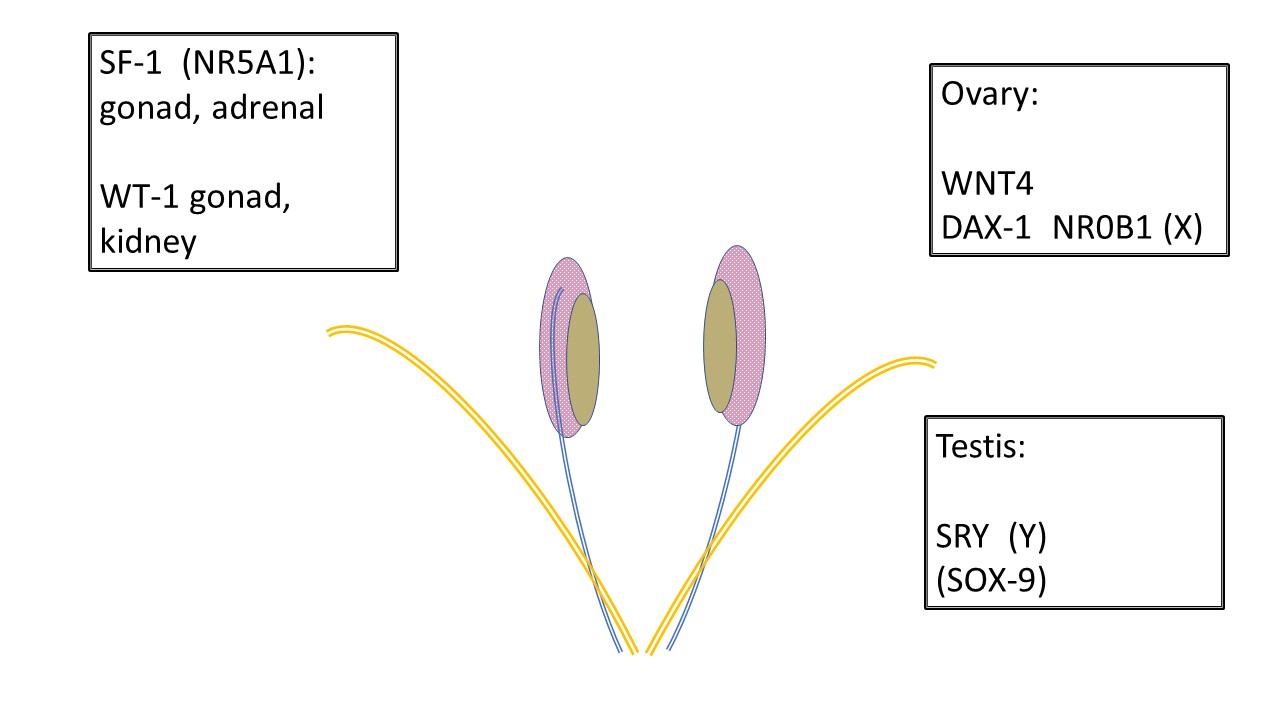

All developing fetuses begin the same. Anatomical resources for either male or female development and variations are present in the early weeks of gestation (Table 2) including gonadal ridge, Wolffian (mesonephric) and Müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts, cloaca and subsequent urogenital sinus, genital tubercle and labioscrotal swellings. Figure 1 shows genes responsible for development of the undifferentiated gonad to either a testis or an ovary.

Table 2 Embryologic Precursors and Typical Male/Female Structures.

| Embryologic Structure | Female-Typical Structure | Male-Typical Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Gonadal Ridge | Ovary | Testicle |

| Wolffian (mesonephric) duct | Paroophoron, epoophoron, Gartner’s duct cyst | Vas defrens, epididymis, seminal vesicles |

| Müllerian (paramesonephric) duct | Fallopian tubes, uterus, proximal vagina | Appendix testis, prostatic utricle |

| Cloaca and subsequent urogenital sinus | Bladder, distal vagina, urethra | Bladder, prostate, urethra |

| Genital tubercle | Clitoris | Penis |

| Labioscrotal swellings | Labial complex | Scrotum |

Figure 1 Development of undifferentiated gonads. All gonads begin the same. Primordial germ cells migrate to the gonadal ridge prior to 6 weeks and the infrastructure to support gonad development is further influenced by various genes. SF-1 and WT-1 have influence over gonadal development and subsequent endocrine communication to the Wolffian (mesonephric-blue) and Müllerian (paramesonephric-orange) ducts. Note the relationship between the mesonephros (pink), mesonephric duct and undifferentiated gonad (tan). WNT4 is the ovary determining gene. DAX-1 is considered the “anti-testis gene.” Duplication of DAX-1 results in XY sex reversal. SRY on the Y chromosome is the testis determining gene. SOX-9 supports Sertoli development but also has homology to participate in testis development in absence of SRY.

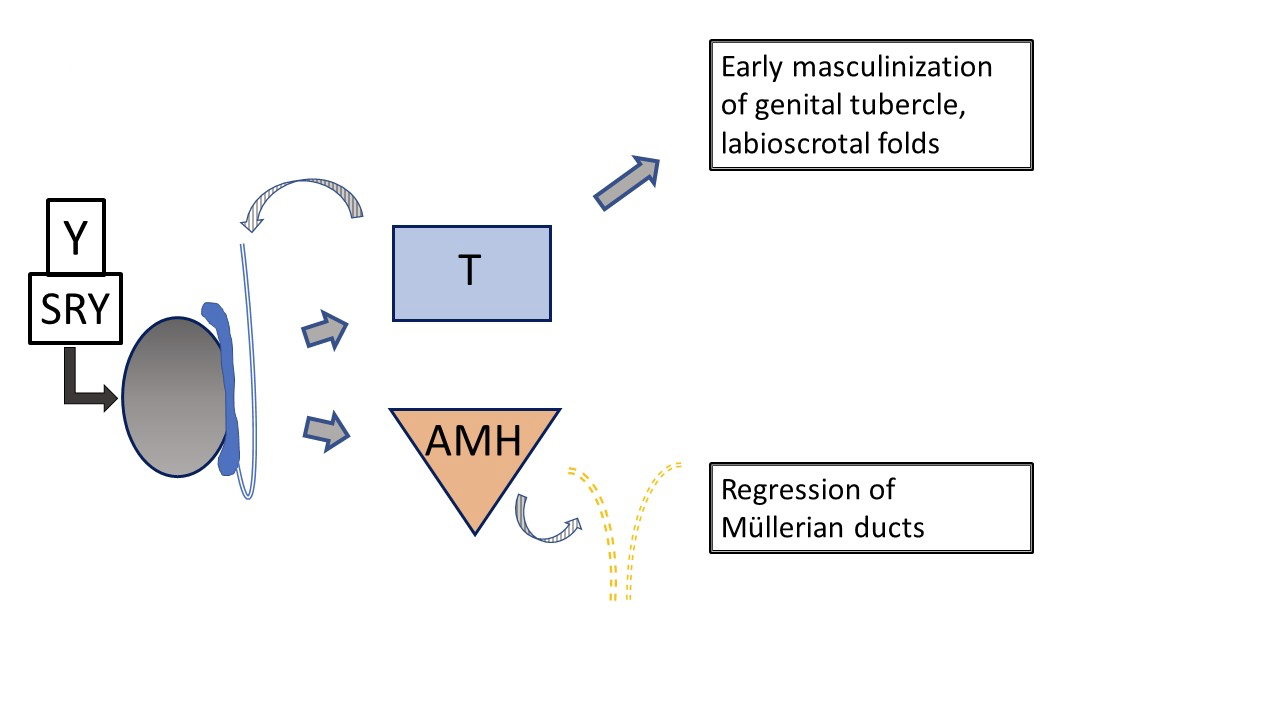

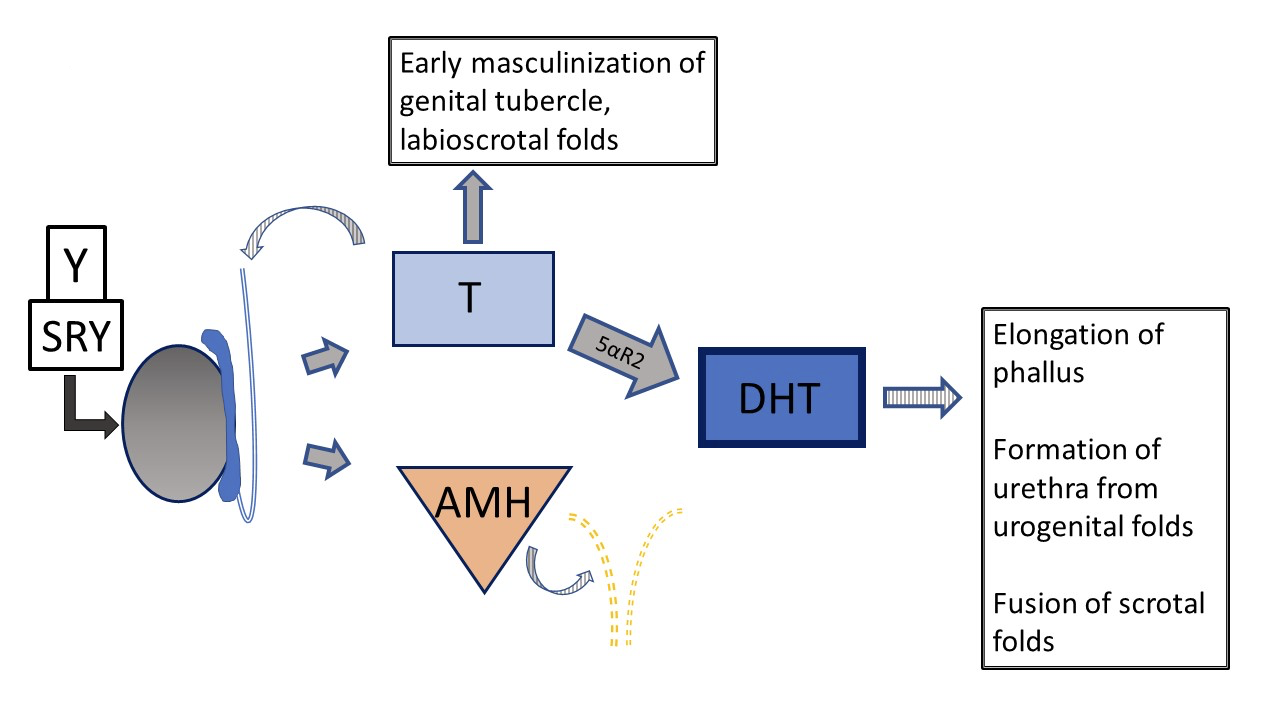

Typical male development (Figure 2) is initiated very early in gestation by the Y chromosome, specifically SRY, determining testicular development. WT-1, SF-1 are involved in development of testis and ovary, and SOX-9 is involved in Sertoli cell differentiation. The Leydig cells of the testis subsequently begin testosterone production at approximately 8 weeks gestation and the Sertoli cells produce anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), inhibiting maturation of the Müllerian ducts into uterus, Fallopian tubes and upper vagina. Testosterone dictates early growth of the genital tubercle and development of the Wolffian duct into vas deferens, epididymis and seminal vesicle. Development or lack thereof in the Wolffian and Müllerian systems occurs as a paracrine rather than systemic action, explaining asymmetric development of ductal structures when the gonad composition is asymmetric. Conversion of testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone (DHT) by 5α-reductase-2 occurs in various tissues and is responsible for further maturation of the penis, tubularization of the urogenital sinus and urethral plate, and closure of the scrotum by 14 weeks gestation. Subsequent growth of the phallic structure occurs because of waning fetal androgen and somatic growth.

Figure 2 Typical early development of male external and internal genital tract, as influenced by fetal testis. Testosterone and AMH production by the fetal testis result in early masculinization of the genital tubercle and regression of Müllerian ducts. Subsequent development of the external genitalia and urethra is influenced by conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. (not depicted here, see Figure 4).

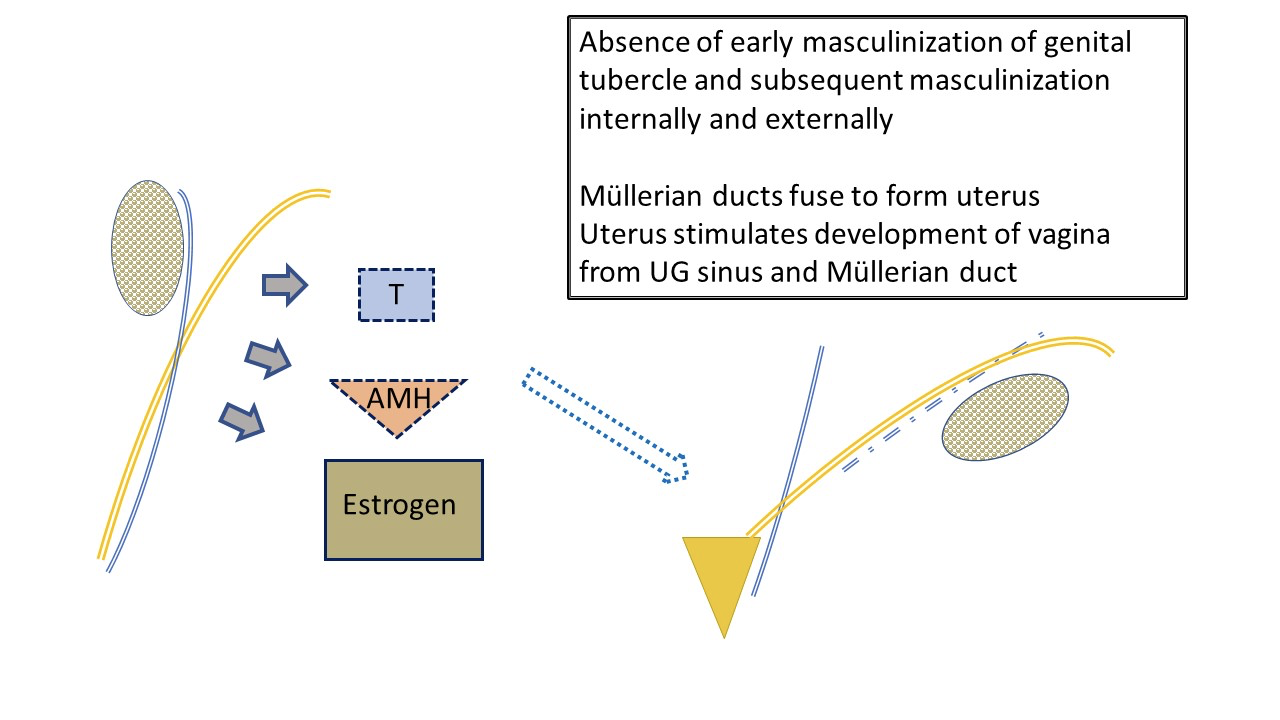

Typical female development (Figure 3) is often viewed as occurring by default since it is not overseen by hormones produced by the testes. Ovarian determination does not figure prominently in embryologic development of the genitalia. Low levels of androgen and AMH allow female typical development of the genital tubercle as clitoris, labioscrotal folds as labial complex, and distal urogenital sinus as urethra and vagina. The paired Müllerian bodies migrate and fuse to form the uterus. Together they stimulate the sinovaginal bulb on the urogenital sinus to begin development of the lower vagina.

Figure 3 Typical early development of female external and internal genital tract, as influenced by fetal ovary. Low level AMH and androgen by the ovary results in development of typical female anatomy: uterus and fallopian tubes, upper vagina. Fetal estrogen production has less impact on female line development than environment with minimal androgen and AMH levels. The labia will be affected by maternal estrogens. Note also the ultimate “water under the bridge” relationship of ureter (branched off mesonephric duct) and fallopian tube. Note mesonephric duct remnants associated with fallopian tube.

Different Pathways that Can Cause DSD

Developmental differences can occur through atypical:

- Genetic determination of the gonads (e.g., mixed gonadal dysgenesis, ovotesticular DSD)

- Hormone production (e.g., 5α-reductase deficiency, 3-β hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency, 21-hydroxylase deficiency CAH, or Luteinizing Hormone [LH] receptor mutations)

- Hormone action (e.g., complete or partial AIS)

- Variations in precursor tissue development/separation of the cloaca (e.g., Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser [MRKH] syndrome, cloacal exstrophy, cloacal anomalies)

Even with a 46,XX or 46,XY karyotype, there is no certainty that development will be along the typical female or male line. In 46,XY alone, numerous differences occur due to Y chromosome mutations that alter testis determination or function, somatic mutations that lead to dysgenesis of the developing testicle, variations in testosterone biosynthesis or conversion, and X-linked mutations that impact androgen receptor function. External phenotype, internal development, potential for spontaneous puberty or fertility, and identification along the gender spectrum can all be affected. In considering the features of the various DSD conditions described below, is important to note that hormone production and action occur on a spectrum. Therefore, deficiencies in receptor function or hormone and converting enzyme production are not necessarily complete deficits. Phenotype can vary widely, even among individuals with the same diagnosis.

Pathophysiology

Variations in development of the internal and external genitalia are directed by sex chromosome and somatic mutations, resultant gonadal function, and tissue response. When receptor function or presence of a pertinent enzyme is atypical due to a known or yet to be identified genetic mutation, the effect on the target organs can be complete (no evident function) or partial. The phenotype varies accordingly. As one example, various phenotypes of androgen insensitivity (complete CAIS, partial PAIS and mild MAIS: spectrum of genital phenotype from typical female—ambiguous—typical male) occur via numerous distinct mutations of the Androgen Receptor gene on the X Chromosome (X-linked recessive condition). Table 3 shows a DSD classification system, divided by karyotype.

Table 3 An Example of a DSD Classification

| Sex Chromosome DSD | 46,XY DSD | 46,XX DSD |

|---|---|---|

| 45,X (Turner syndrome and variants) | Disorders of gonadal (testicular) development: (1) complete gonadal dysgenesis (Swyer syndrome); (2) partial gonadal dysgenesis; (3) gonadal regression; and (4) ovotesticular DSD |

Disorders of gonadal (ovarian) development: (1) ovotesticular DSD; (2) testicular DSD (eg, SRY+, duplicate SOX9); and (3) gonadal dysgenesis |

| 47,XXY (Klinefelter syndrome and variants) | Disorders in androgen synthesis or action: (1) androgen biosynthesis defect (e.g., 17-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency, 5RD2 deficiency, StAR mutations); (2) defect in androgen action (e.g., CAIS, PAIS); (3) luteinizing hormone receptor defects (e.g., Leydig cell hypoplasia, aplasia); and (4)disorders of anti-Müllerian hormone and anti-Müllerian hormone receptor (persistent Müllerian duct syndrome) |

Androgen excess: (1) fetal (eg, 21-hydroxylase deficiency, 11-hydroxylase deficiency); (2) fetoplacental (aromatase deficiency, POR [P450 Oxidoreductase]); and (3) maternal (luteoma, exogenous, etc) |

| 45,X/46,XY (MGD, ovotesticular DSD) | Other (eg, cloacal exstrophy, vaginal atresia, MURCS [Müllerian, renal, cervicothoracic somite abnormalities], other syndromes) | |

| 46,XX/46,XY (chimeric, ovotesticular DSD) |

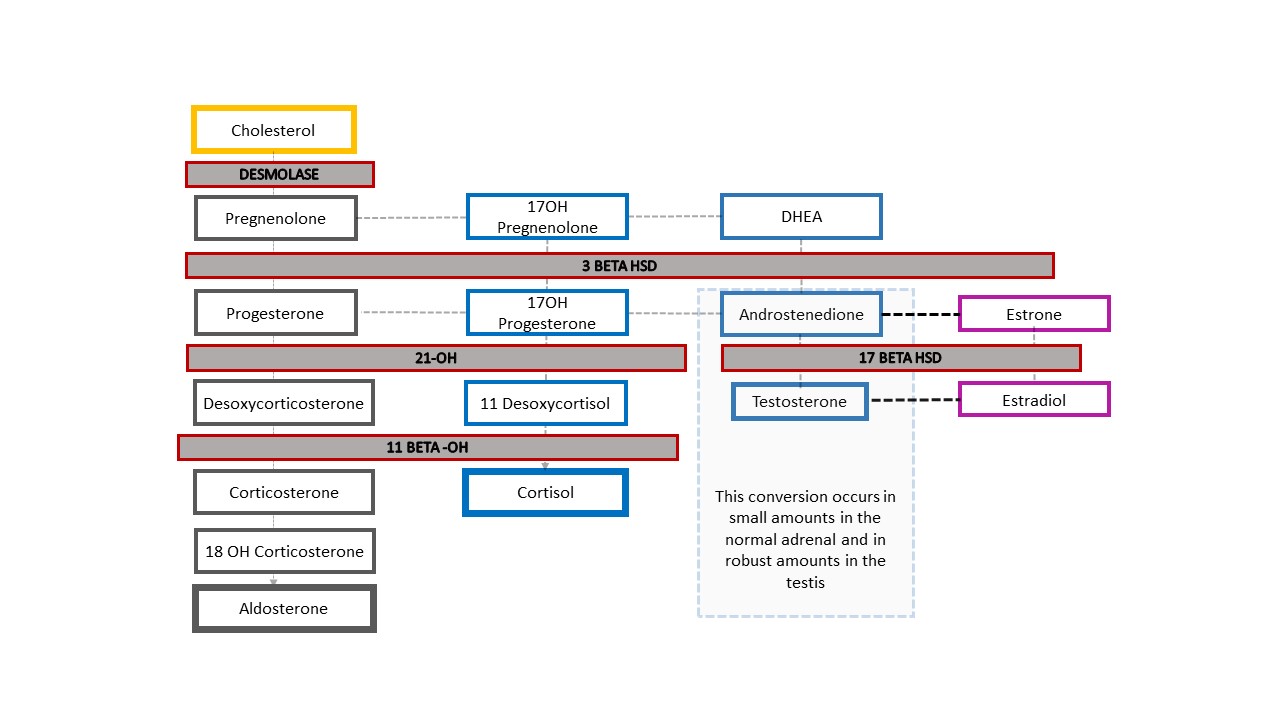

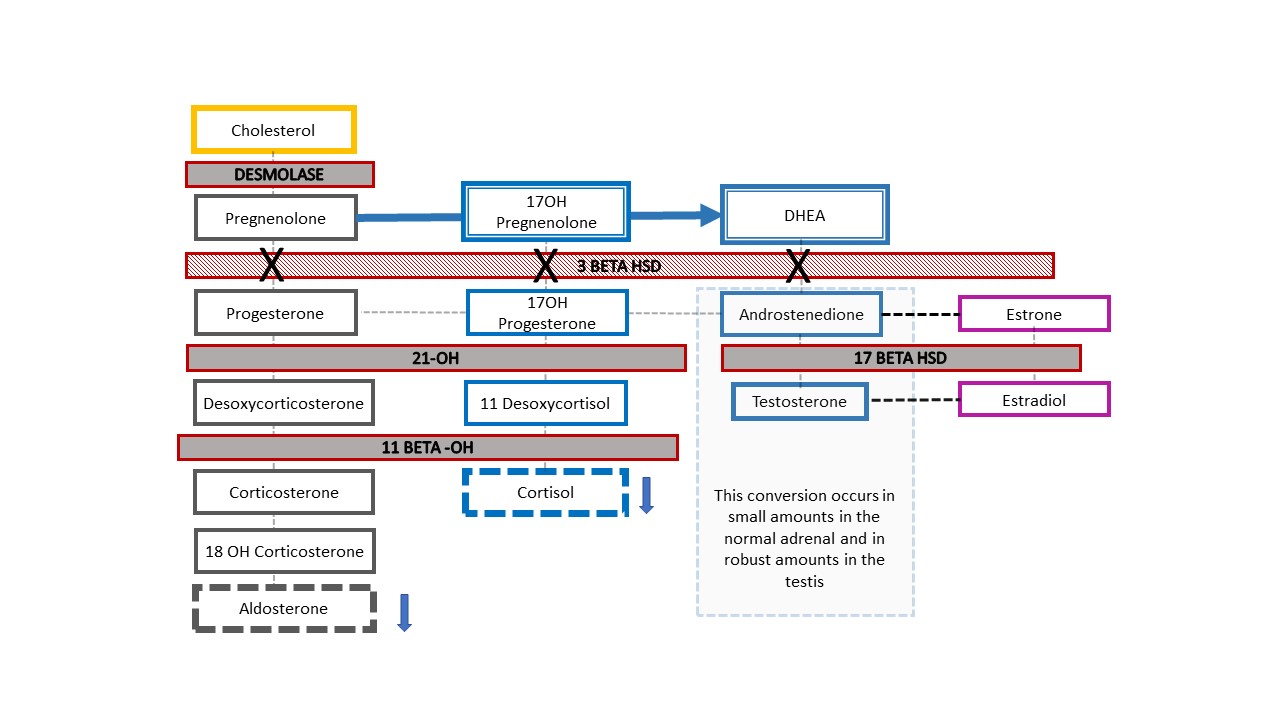

46,XX DSD

The most common form of 46,XX DSD is CAH, in which adrenal enzymatic function is impaired. Figure 4 shows the typical adrenal steroid cascade, which begins with cholesterol. End products are aldosterone, cortisol, and sex steroids. The sex steroid arm of the cascade ends with androstenedione which is converted to a small amount of testosterone. Production of testosterone in the Leydig cells of the testis likewise begins with cholesterol. In CAH, reduced enzyme function causes reduced mineralocorticoids (aldosterone) and glucocorticoids (cortisol), and shunting toward sex steroid production. The result is masculinization of a fetus with 46,XX karyotype. Although a complete absence of enzymatic function and downstream adrenal steroid products is easiest to remember, the function may be only partially impaired and feedback in the hypothalamic-pituitary axis affected accordingly.

Figure 4 Steroid cascade and spectrum of CAH diagnoses. Any degree of defect in production of an enzyme results in decreased downstream product and shunting of the cascade toward the sex steroids. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is stimulated to compensate. Increased ACTH results in adrenal cortex hyperplasia and further increased production of precursors.

Typical anatomy of a patient with 46,XX CAH includes varying degrees of clitoral enlargement and urogenital sinus formation. Gonads are ovaries and are not palpable. There are several mutations that lead to different characteristic textbook adrenal steroid milieus and physical and physiological phenotypes. The most common form is 21-hydroxylase deficiency. Infants with 46,XX CAH can experience life-threatening salt wasting at about 1 week of life, so this diagnosis must considered for all infants with ambiguous genitalia. An elevated 17-OH-progesterone is diagnostic. Female gender identity and sex of rearing is most frequent, though not universal.

46,XY DSD

Within the category of 46,XY DSD, a range of disorders of gonadal development and androgen synthesis and action exist, as detailed in Table 3. Along with the spectrum of AIS conditions detailed above, complete or partial gonadal dysgenesis can result in similar anatomic variations: an infant with 46,XY chromosomes and either typical female or ambiguous phenotype (e.g., proximal hypospadias with penoscrotal transposition, and one or both gonads undescended). Individuals with complete AIS and complete gonadal dysgenesis are typically raised female, and identify as female; those with partial forms of either condition have more variability in sex of rearing and gender identity.

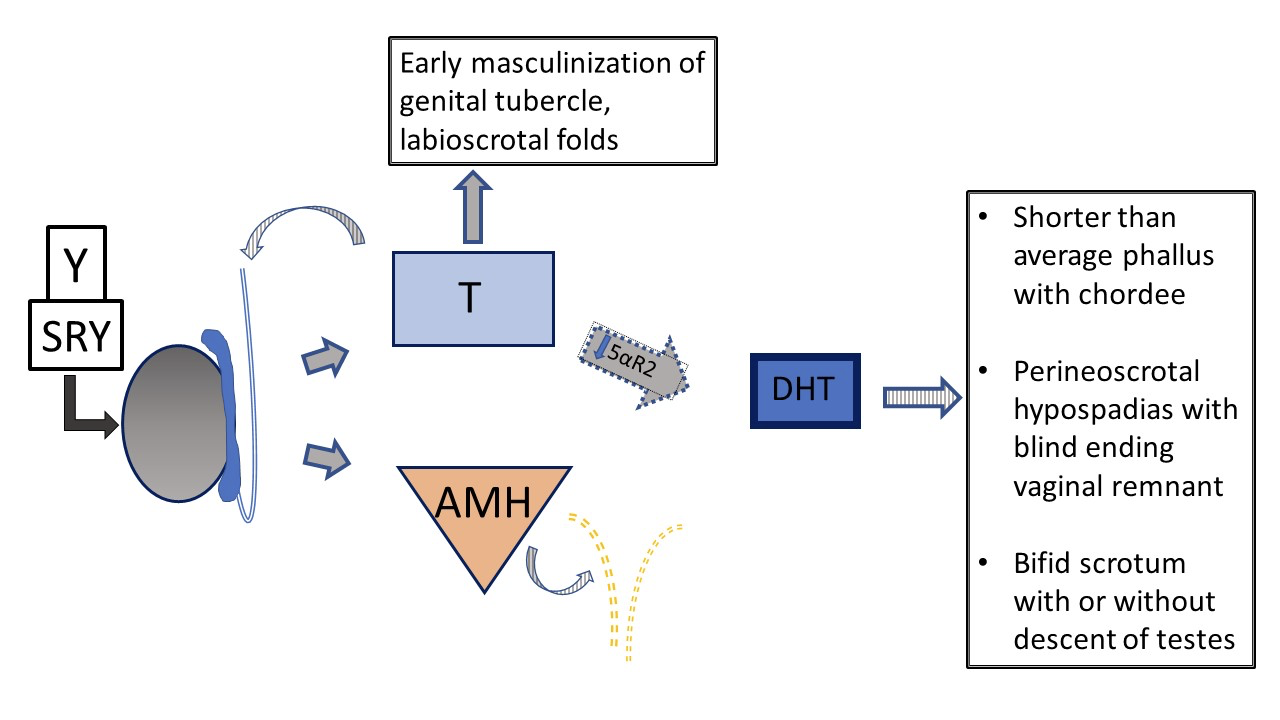

Another 46,XY DSD, 5α-reductase deficiency, causes reduced conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), resulting in variable genital phenotype. Figure 5 and Figure 6 compare the typical testicular development pathway to the pathway that occurs in patients with 5α-reductase deficiency.

Figure 5 Typical 46XY prenatal genital development Development can deviate from “typical” at several different steps. Striped arrows signify paracrine type function. Dashed lines indicate regression of Müllerian ducts early in development.

Figure 6 46XY prenatal genital development in patients with vs 5-α-reductase deficiency. Testes are determined and have normal testosterone and AMH production. There is no uterus. Due to impaired 5-α-reductase function, the ratio of T /DHT is notably increased. In the setting of lower DHT, there is variability in phenotype from typical female to typical male to ambiguous genital anatomy. With severe deficiency, phallus and urogenital sinus development are arrested at early stage of masculinization, with a single urogenital orifice in the perineal region and no fusion of the labioscrotal folds.

Figure 7 shows the resultant adrenal cascade in the rare example of a patient with 46,XY CAH who presents clinically with ambiguous genitalia: 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [HSD] deficiency. The enzyme blockage occurs before conversion of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) to androstenedione in the adrenal steroid cascade, so infants experience reduced mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids along with a difference in genital development. Like babies with 46,XX CAH and 21-hydroxylase or 11β-hydroxylase deficiency, infants with 3-β-HSD deficiency can experience life threatening salt wasting. Diagnosis is made through elevated 17-OH pregnenolone and DHEA.

Figure 7 3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency steroid pathway. This relatively proximal defect in the adrenal cholesterol cascade results in severe corticosteroid and mineralocorticoid deficiency. It is unique, in that 46,XY babies with CAH have under-masculinized genital appearance while 46,XX babies have genital appearance of typical (or nearly typical) female. When a newborn with prenatally detected Y chromosome is born with ambiguous appearance of the genitalia, this is the one CAH diagnosis to rule out. Elevated 17-OH-pregnenolone and DHEA help make the diagnosis.

Sex Chromosome DSD

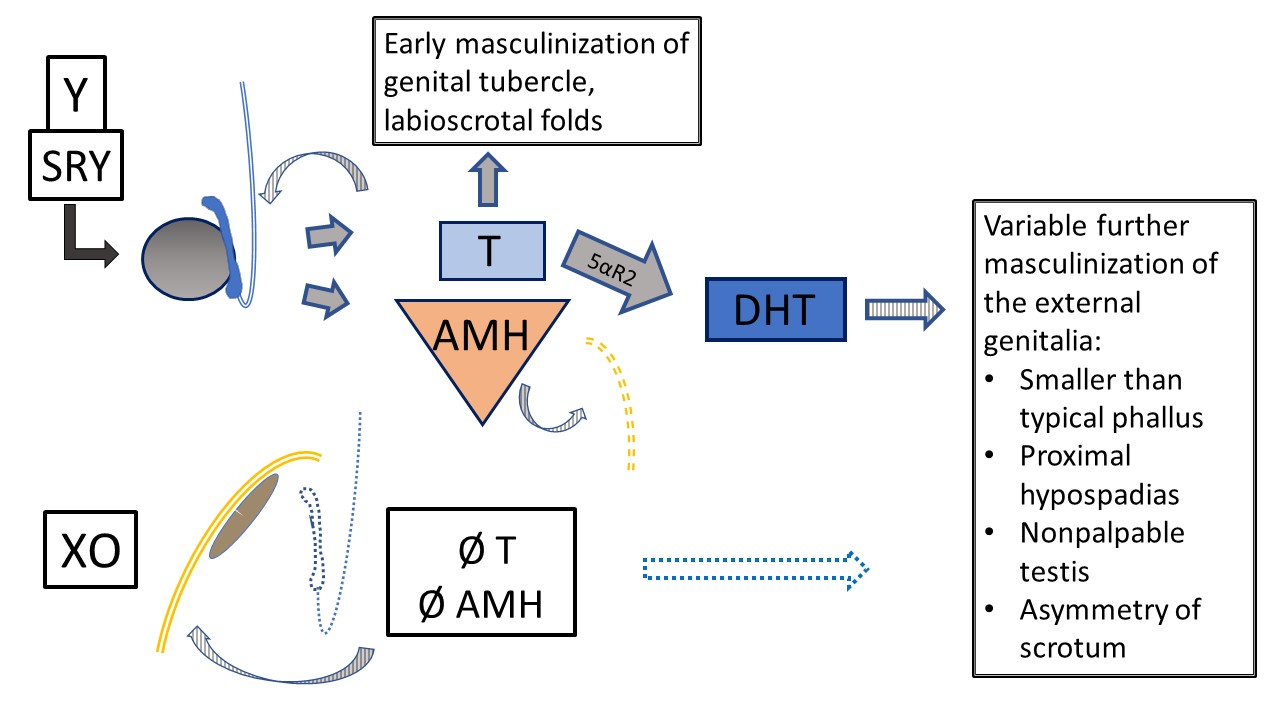

Of the sex chromosome DSD diagnoses listed in Table 3, the conditions with a 45,X/46,XY (or similar) mosaic karyotype warrant particular mention. Patients with this karyotype can have female-typical external genitalia (Tuner Syndrome with Y chromosome material [TS+Y]), ambiguous genitalia (mixed gonadal dysgenesis [MGD]), or male-typical external genitalia. Patients with TS+Y have increased risk of gonadal tumors, differing from patients with 45,X Turner syndrome. Phenotype and sex of rearing/gender identity is variable in MGD, though result is frequently gonadal and labioscrotal asymmetry, as detailed in Figure 8. Any patient with 45,X/46,XY karyotype can have manifestations of TS (e.g., aortic coarctation, renal anomalies), so should undergo the same systemic screening tests as classic TS patients.7,8

Figure 8 45,X/46,XY Mixed gonadal dysgenesis. Multiple phenotypes occur with this mosaic karyotype. This diagram represents internal and external development in the setting of one testis (determined by Y chromosome) and one streak gonad (default development, ovarian-type stroma). The classic phenotype, when a degree of ambiguity is observed, is one nonpalpable gonad, one descended testis, and proximal hypospadias. As T and AMH have paracrine function, the streak gonad is associated with hemiuterus and fallopian tube with no Wolffian structures. Due to Y material, there is risk of gonadoblastoma and dysgerminoma. The testis has variable dysgenetic development impacting early and future function and tumor risk. Primary masculinization occurs but further development of the urethra and scrotum is variably impacted by testis function.

Ovotesticular DSD

Ovotesticular DSD occurs when there is both ovarian and testicular tissue present in the same individual (former name – true hermaphroditism). Typically, the ovarian tissue is more well developed, and the testicular tissue is dysgenetic. Phenotype, sex of rearing/gender identity, and fertility potential are all variable. Importantly, patients with ovotesticular DSD can have any karyotype (though 46, XX is most common), so this diagnosis must be considered for any patient who presents with ambiguous genitalia.

Multidisciplinary Evaluation

Beyond proposing less pejorative nomenclature, other cornerstones of the 2006 consensus statement are paradigm are counseling by a multidisciplinary team and longitudinal psychosocial support of patients and parents.1

The Multidisciplinary Team

The team who works with a family as a newborn inpatient consultation is preferably the same who will work with patients and families longitudinally. The team is responsible for educating the family on the condition and all potential management options; it provides support and engages the family in shared decision making where decisions are required (e.g., sex of rearing, disclosure, surgery). The team ideally includes the following members:

- Endocrinology

- Mental Health (Psychologist, Social Worker)

- Urology / Pediatric Surgery / Gynecology

- Genetic Counselor / Geneticist

- Nursing

- Patient advocate / Patient educator

- Neonatologist (inpatient consultation)

Each specialist brings different perspectives, relevant clinical expertise, and interpersonal skills to the multidisciplinary team. Surgeons are an important part of the team despite early or urgent surgical needs being uncommon. All are exposed to team discussions and contribute to the patient and family experience. Ideally, mutual respect and willingness to consider all perspectives enhances team functioning and allows the team to provide even higher-level care over time, particularly as standards of care evolve.

Each individual living with a DSD condition may not have access to a functional multidisciplinary team. Some may not embrace work with the team or may find longitudinal follow-up burdensome. Each early opportunity for education about the diagnosis and potential long-term concerns or medical needs is therefore very important. In situations where long-term follow-up is feasible and acceptable, this can be accomplished in the context of more regular single specialty care, as appropriate for the patient. For example, some of the patients with CAH at the authors’ institution follow with their endocrinologist quarterly and participate a full multidisciplinary team visit yearly.

Actively working together, learning from each other and from patients/families, facilitates team functioning and advances care. The team draws upon prior experiences and assimilates new knowledge, particularly in the realms of patient experience and next generation genetic testing. The team also identifies gaps in knowledge and within the care paradigm that can be addressed through collaborations and intentional research. Periodic case- or topic-based multidisciplinary conference helps build fluency in the various conditions for team members and learners and allows opportunity to understand differences in philosophy.

Initial Approach to the Patient with a Suspected DSD

Patients with suspected DSD classically present in infancy with ambiguous genitalia, or in adolescence with primary amenorrhea. DSD conditions can also come to medical attention due to incidental imaging or intraoperative findings, an inguinal hernia in a girl, or if girl experiences masculinization at the time of puberty Increasingly, DSD conditions are suspected prenatally due to cell free DNA-ultrasound discordance, or concern for a difference in genital development seen on ultrasound.

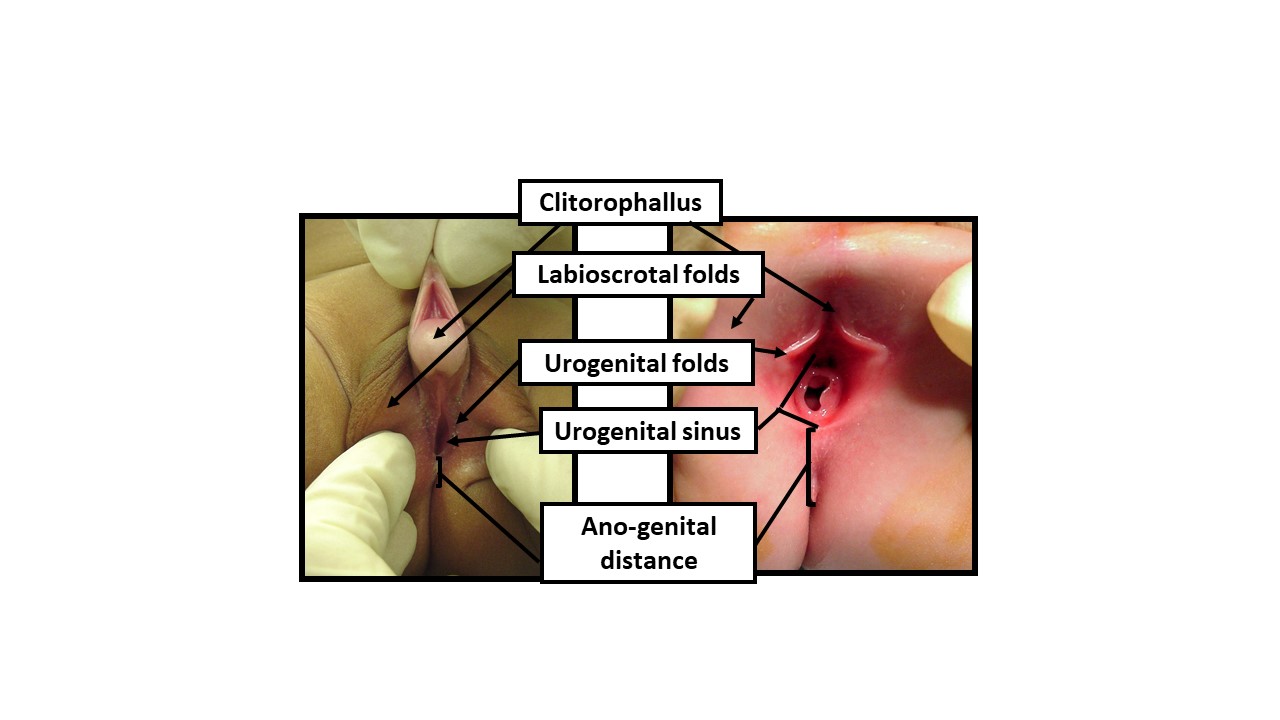

When an infant with a suspected DSD is born, consultation with a multidisciplinary team (described above) is recommended whenever feasible. Remember to congratulate the family on their new baby (a step that is often overlooked, especially when there is surprise about, or of lack of familiarity with, DSD). Utilize gender-neutral terms, (“your baby”, not “it”) when referring to the infant if there is any question about sex assignment. Figure 9 shows recommendations for describing the newborn genital exam, including gender neutral terms to use. Along with a detailed prenatal history, family history, and physical exam, recommendations for initial evaluation of a patient with suspected DSD include:

- Karyotype

- Endocrine testing (17-OH-progesterone, testosterone, luteinizing hormone, follicle stimulating hormone, electrolytes)

- Pelvic ultrasound to evaluate for gonadal position and type, and for presence of Mϋllerian structures

Figure 9 Describing the newborn exam with gender-neutral anatomical terms. When examining a newborn with an ambiguous appearance of the genitals, gender-neutral terminology should be utilized until sufficient data permits shared decision-making with the parents for determination of sex of rearing. The exam should document the following reflections of androgen exposure: 1) Length of clitorophallic structure, 2) Width of glans, 3) Number and position of perineal orifices, 4) Degree of fusion of labioscrotal folds, 5) Hyper-pigmentation and rugation of labioscrotal folds, 6) Anogenital distance, 7) Location of any palpable gonads

An algorithmic approach based on the number of palpable gonads and results of endocrine, genetic, and imaging as above can efficiently help to narrow the differential diagnosis. Most medically critical in the newborn is to rule out life-threatening salt-wasting CAH. The entire multidisciplinary team described above plays a role during this critical diagnostic period to help the family integrate new pieces of information, and to make decisions about sex of rearing, disclosure, and surgery.

Surgical Management Options

Surgical options for patients with DSD are highly individualized, and decisions about surgical treatment should ideally be made in the context of a multidisciplinary team. Depending on the patient’s needs and goals, procedures can be diagnostic, reconstructive, or extirpative.

Diagnostic Procedures

Diagnostic procedures are often pursed when the anatomy or diagnosis remain unclear after endocrine and genetic evaluation, and detailed radiologic imaging.

Endoscopy provides for detailed visualization and measurements of the urogenital tract. For example, the length and configuration of a urogenital sinus can be characterized. Vaginal structures can be evaluated for depth, number, and presence or absence of a cervix.

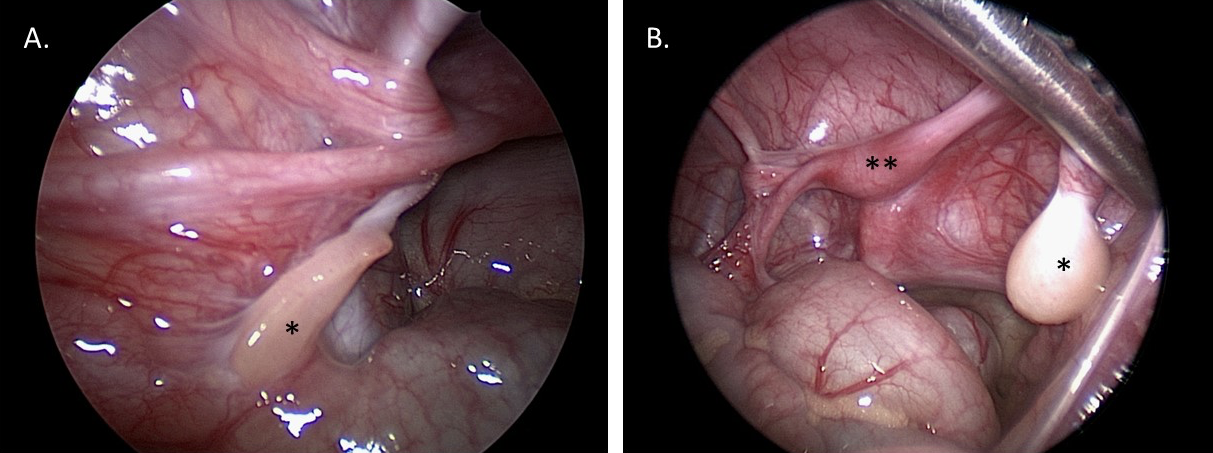

Diagnostic laparoscopy assists with visualization of gonads and Müllerian structures. This visualization can aid in diagnosis, and provide information for future reconstructive surgical planning. Gonadal biopsy can be performed via laparoscopic or open approach to determine tissue type (for example, if ovotesticular DSD is suspected), or sent for karyotype if Y chromosome material is suspected but has not been identified on peripheral blood karyotyping. Figure 10 shows laparoscopic still images from a patient with MGD: the MGD diagnosis was suspected clinically, and confirmed with the gross and histological gonadal appearance provided by diagnostic laparoscopy and biopsy.

Figure 10 Diagnostic laparoscopic images of the pelvis in a 1-year-old patient with mixed gonadal dysgenesis. A. *Left streak gonad. B. *Right dysgenetic testis. **Uterus.

Masculinizing Genitoplasty

For patients with DSD, masculinizing genitoplasty most frequently involves a proximal hypospadias repair, often with scrotoplasty to correct penoscrotal transposition and/or a bifid configuration. The technical details of hypospadias repair are similar to patients without a defined DSD condition. Hypospadias repair in patients with DSD typically requires a two-stage procedure to achieve correction of chordee and a terminal urethral meatus. There is controversy in the literature about whether patients with a known DSD diagnosis have poorer hypospadias surgical outcomes as compared to patients with proximal hypospadias who do not have a specific DSD.9,10,11

Feminizing Genitoplasty

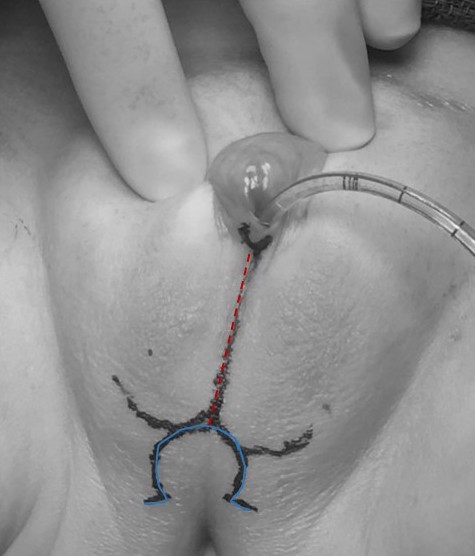

Components include clitoroplasty (with labioplasty), and vaginoplasty. A variety of approaches exist, which can be tailored based on patient anatomy and goals. Example preoperative surgical markings for a patient with CAH who underwent a partial urogenital mobilization (PUM) and labioplasty without clitoroplasty is illustrated in Figure 11.

Clitoroplasty and Labiaplasty

The most frequently reported modern clitoroplasty procedures involve a nerve sparing clitoral reduction.12 The clitoris is degloved and corporal (erectile) tissue removed, avoiding the dorsal neurovascular bundles. The tunica albuginea sparing approach to reduction clitoroplasty was introduced further preserve glandular blood supply and sensation, and involves ventral corporal incisions, and excision of erectile tissue, while preserving the surrounding tunica. The glans of the clitoris is frequently preserved, recessed proximally, and secured beneath the pubis. Glans reduction can be performed by excising a ventral wedge of tissue and reapproximating the ventral edges to one another. However, this approach carries a risk of reduced glandular sensation. A concealed clitoris can often be achieved with clitoroplasty along with labioplasty such that glans reduction is becoming less frequent.

Several corporal sparing techniques have emerged as alternatives to the clitoral reduction procedure described above. As one example, Pippi Salle described a corporal disassembly procedure.13 For this procedure, the corporal bodies are completely separated from the glans and neurovascular bundle, and from one another. The corporal bodies are then individually tunneled into their respective ipsilateral labia majora, and the glans repositioned proximally, similar to the clitoral reduction procedures. This ‘Pippi Salle procedure’ has the theoretical advantage of reversibility, as no tissue is removed, though attempts at reversal, and other long-term outcomes, have not yet been reported.

Labioplasty is typically the final step of a clitoroplasty (with or without vaginoplasty) procedure. The goals are to reconfigure the clitoral hood and shaft tissue over the clitoris to conceal the glans, and to advance the skin edges posteriorly, lateral to the vestibule/vaginal opening.

Vaginoplasty

The approach to vaginoplasty involves an assessment of whether the patient has a urogenital sinus with a low confluence (short common channel with separation of vagina and urethra close to perineum) or high confluence (longer common channel and higher separation.14

A perineal skin flap vaginoplasty (Fortunoff technique) can be sufficient for patients with a low confluence urogenital sinus. For this technique, a posterior U-shaped flap is created (as in Figure 11) The posterior wall of the vagina is then incised proximal to the dysplastic confluence, and the flap positioned and secured within this vaginal incision to increase the vaginal caliber.

Figure 11 Preoperative surgical marking for a patient with congenital adrenal hyperplasia who is to undergo a partial urogenital mobilization and labioplasty without clitoroplasty. A catheter is noted within the urogenital sinus opening. The midline marking (dashed red) extends through the fused labioscrotal folds, and the omega shaped mark (solid blue) will form the posterior skin flap for vaginoplasty.

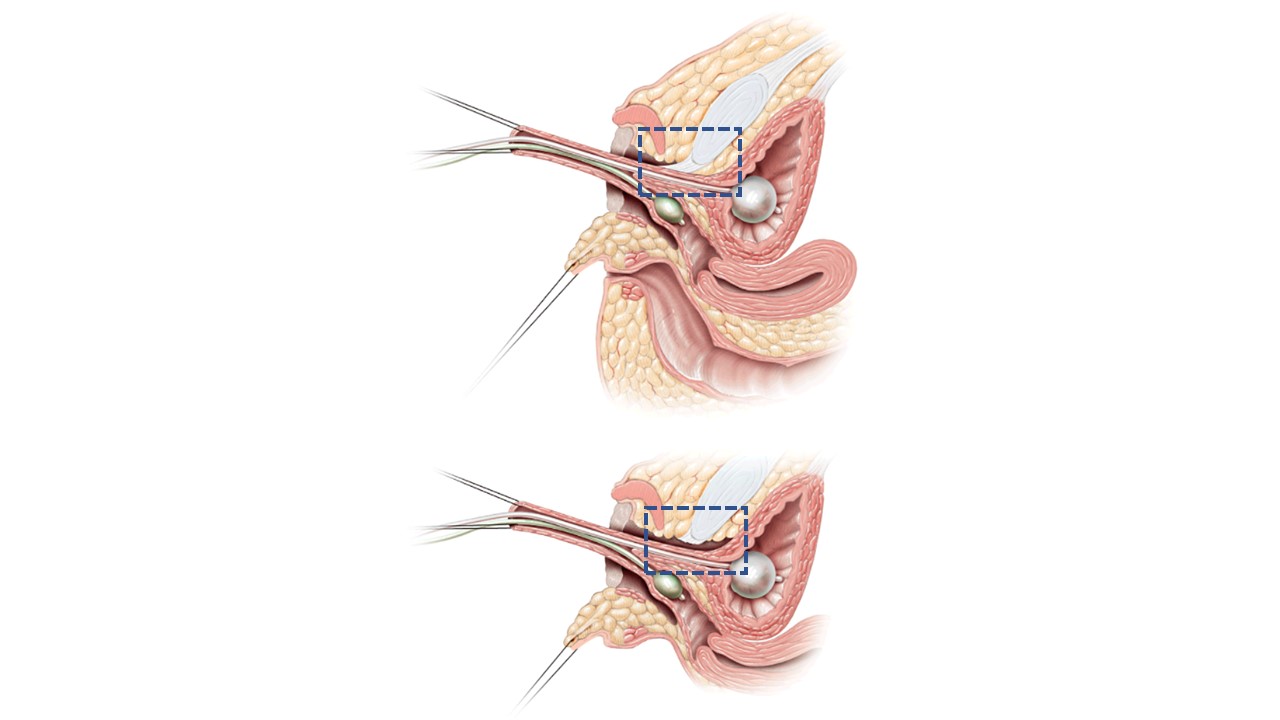

In total urogenital mobilization (TUM) or partial urogenital mobilization (PUM), the urethra and vagina are be mobilized toward the perineum as a unit.15 The distinction between the two is whether anterior dissection behind the pubis takes the pubourethral ligament, as shown in Figure 12. There is the potential concern for urinary incontinence with more extensive mobilization but that has not been definitively demonstrated, and is likely more of a concern if the distance from confluence to bladder neck is foreshortened. If applied to low confluence cases, PUM generally brings vagina to a range where it can be exteriorized or bridged with a posterior based perineal flap (see above). High confluence signifies a more complex anatomy including a longer distance to reach the perineum, a closer relationship between vagina and bladder neck, and often a shorter vagina. Direct pull-through may not be advantageous in the long run. In the high confluence cases, even with urogenital mobilization, the vagina will need to be separated from the urogenital sinus and pulled through to the perineum. In this scenario, the urogenital sinus becomes the urethra. The vagina reaches the perineum with the assistance of perineal skin flaps or use of excess mobilized urogenital sinus tissue as a flap.

Figure 12 Sagittal cross-sectional images of partial vs total urogenital mobilization. A. Partial urogenital mobilization: urethra and vagina are advanced towards the perineum as a unit. Pubourethral ligament (blue dashed line box) is left intact. B. Total urogenital mobilization: urethra and vagina are advanced towards the perineum as a unit. Pubourethral ligament (blue dashed line box) is divided. Adapted From: Rink RC, Cain MP. Urogenital mobilization for urogenital sinus repair. BJU Int 2008; 102 (9): 1182–1197. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.08091.x. (permission granted 2/1/2022)

For patients who are born with absent or poorly developed Müllerian structures, vaginoplasty involves blunt creation of a neovagina in the retrovesical space between the bladder and rectum, and then lining the new potential space with either autologous tissue (e.g., skin graft, buccal mucosa graft, peritoneal flap) or other biologic grafts (e.g., small intestinal submucosa [SIS]). These techniques can also be used as an adjunct to the procedures described above, or in the reoperative setting.

Vaginal Dilations

Some patients with DSD (e.g., complete AIS) can achieve a vagina that will permit comfortable, pleasurable sexual activity with regular vaginal dilations, without needing a surgical vaginoplasty. All patients who undergo a surgical vaginoplasty also require vaginal dilations while healing from surgery, and until they are having vaginal intercourse on a consistent basis.

Gonadectomy and Gonadal Management

The paradigm for gonadal management in patients with DSD has evolved over time. Traditionally, patients with DSD conditions where there is an increased risk for tumor formation were counseled to undergo gonadectomy. Infertility was assumed. Over time, it has become evident that there is a wide range of tumor risk, and that the tumors that form are frequently gonadoblastoma (not malignant).16,17 Dysgerminomas (malignant germ cell tumors) are possible, but exceedingly rare before puberty. There also may be non-traditional fertility potential for some who were previously considered to be infertile.18 Thus, gonadal management recommendations are becoming more individualized, considering patient diagnosis (and thus predicted tumor risk), age, and potential for endogenous gonadal function (both hormonal and reproductive). For patients who elect for gonadectomy, gonadal tissue cryopreservation is an emerging option that may allow for biology fertility, assuming expected future advances in assisted reproductive technologies occur.19 No evidence-based surveillance protocols are yet available for patients who elect to retain their gonads; the authors’ institution typically recommends pelvic ultrasound every 6–12 months. Table 4 shows gonadal recommendation strategies for several DSD diagnoses.

Table 4 Gonadal Management Options by Diagnosis. * consider experimental gonadal tissue cryopreservation.

| Diagnosis | Estimated Tumor Risk | Germ Cells Expected? | Puberty Expected? | Gonad Management Options |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 46, XY Complete Gonadal Dysgenesis (Swyer Syndrome) | High – Up to 35% |

No (maybe precursor germ cells) |

No | -Gonadectomy* |

| Partial Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome | High – Up to 50% depending on gonad location |

Yes Sperm possible |

Yes, variable | -Orchidopexy, consider biopsy -Observation w/ ultrasounds -Gonadectomy* |

| Turner Syndrome + Y Chromosome | Medium – ~10-30% |

Maybe – Eggs possible | Possible | -Observation w/ultrasounds -Gonadectomy* (standard, low level of evidence) |

| Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome | Low – ~2-10% |

Yes – Sperm precursors |

Yes – due to aromatization of testosterone to estrogen | -Postpubertal gonadectomy* -Observation w/ultrasounds, MRI |

Management of Mϋllerian Structures

For patients who are being raised male and have persistent Mϋllerian structures (i.e., a large utricle), are typically left in place unless they become symptomatic. Excision risks potential damage to vasal structures (and possibly or pelvic nerves), and patients are frequently asymptomatic. Hypospadias repair is safe, and excision of even large utricular structures is not mandatory before hypospadias repair. If symptoms such as infections or bothersome cyclic hematuria occur, then surgical excision can be pursued through an open, laparoscopic or robotic approach. Hormonal management with menstrual suppression can also be considered for patients who experience cyclic pain to due to an obstructed Mϋllerian remnant, or bothersome cyclic hematuria.

Conclusions

DSDs encompass a wide range of conditions that result from abnormal chromosomal, gonadal, or anatomic development. A wide range of phenotype exists, even within specific DSD diagnoses and categories. A multidisciplinary approach to evaluation and long-term follow up is recommended, whenever possible.

Key Points

- Medically accepted DSD terminology is not preferred by all affected individuals and their families. In individual clinical encounters, ask patients and families which terms they prefer to use when referring to diagnosis and anatomy.

- DSD conditions occur due to atypical chromosomes, gonads, or hormone action. Thinking through the level of abnormality, and determining whether the defect identified is complete or partial, can help predict patient phenotype.

- The number of palpable gonads sets the foundation for a DSD differential diagnosis. The differential is further refined through karyotype, endocrine labs, and pelvic ultrasound.

- Remember to congratulate new parents who have an infant with a suspected DSD—this critical step is often forgotten.

- CAH is the most common form of 46, XX DSD. Clinical features include masculinized external genitalia with non-palpable gonads. Life threatening salt wasting can occur at 1 week of life.

- Ovotesticular DSD can occur in a patient with any karyotype.

- A patient with a 45, X/46, XY karyotype can have female-typical, ambiguous, or male-typical external genitalia. Any patient with this karyotype can have systemic manifestations of Turner Syndrome.

Suggested Readings

- Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF. Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders. Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines &Amp; Policies 2006; 118: 1317–1317. DOI: 10.1542/9781610021494-part06-consensus_statement2.

- Kaefer M, Diamond D, Hendren WH. The Incidence Of Intersexuality In Children With Cryptorchidism And Hypospadias: Stratification Based On Gonadal Palpability And Meatal Position. J Urol 1999; 162 (3 Part 2): 1006–1007. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68049-2.

- Kim S, Rosoklija I, Johnson EK. Surgical, Patient, and Parental Considerations in the Management of Children with Differences of Sex Development. Curr Pediatr Rep 2018; 6 (3): 209–219. DOI: 10.1007/s40124-018-0177-4.

- Mouriquand PD, Gorduza DB, Gay CL. Re: “Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?” J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (6): 442–443. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.07.013.

- Nixon R, Cerqueira V, Kyriakou A, Lucas-Herald A, McNeilly J, McMillan M, et al.. Prevalence of endocrine and genetic abnormalities in boys evaluated systematically for a disorder of sex development. Hum Reprod 2017; 32 (10): 2130–2137. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dex280.

- Van Batavia JP, Kolon TF. Fertility in disorders of sex development: A review. J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (6): 418–425. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.09.015.

References

- Lee PA, Houk CP, Ahmed SF. Consensus Statement on Management of Intersex Disorders. Pediatric Clinical Practice Guidelines &Amp; Policies 2006; 118: 1317–1317. DOI: 10.1542/9781610021494-part06-consensus_statement2.

- Johnson EK, Rosoklija I, Finlayson C. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Attitudes towards "disorders of sex development" nomenclature among affected individuals. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2017; 13: 608. DOI: 10.3410/f.727655647.793533819.

- D’Oro A, Rosoklija I, Jacobson DL, Finlayson C, Chen D, Tu DD, et al.. Patient and Caregiver Attitudes toward Disorders of Sex Development Nomenclature. J Urol 2020; 204 (4): 835–842. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001076.

- Davies JH, Knight EJ, Savage A, Brown J, Malone PS. Evaluation of terminology used to describe disorders of sex development. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (4): 412–415. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.07.004.

- Lin-Su K, Lekarev O, Poppas DP, Vogiatzi MG. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia patient perception of ‘disorders of sex development’ nomenclature. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol 2015; 2015 (1): 9. DOI: 10.1186/s13633-015-0004-4.

- Snodgrass W, Macedo A, Hoebeke P, Mouriquand PDE. Hypospadias dilemmas: A round table. J Pediatr Urol 2011; 7 (2): 145–157. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.11.009.

- Wu Q, Wang C, Shi H, Kong X, Ren S, Jiang M. The Clinical Manifestation and Genetic Evaluation in Patients with 45,X/46,XY Mosaicism. Sex Dev 2017; 11 (2): 64–69. DOI: 10.1159/000455260.

- Das DV, Jabbar PK. Clinical and Reproductive Characteristics of Patients with Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis (45,X/46, XY). J Obstet Gynaecol India 2021; 71 (4): 399–405. DOI: 10.1007/s13224-021-01448-3.

- Saltzman AF, Carrasco A, Colvin A, Campbell JB, Vemulakonda VM, Wilcox D. Patients with disorders of sex development and proximal hypospadias are at high risk for reoperation. World J Urol 2018; 36 (12): 2051–2058. DOI: 10.1007/s00345-018-2350-3.

- Ochi T, Ishiyama A, Yazaki Y, Murakami H, Takeda M, Seo S, et al.. Surgical management of hypospadias in cases with concomitant disorders of sex development. Pediatr Surg Int 2019; 35 (5): 611–617. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-019-04457-6.

- Palmer BW, Reiner W, Kropp BP. Proximal Hypospadias Repair Outcomes in Patients with a Specific Disorder of Sexual Development Diagnosis. Adv Urol 2012; 2012: 1–4. DOI: 10.1155/2012/708301.

- Kaefer M, Rink RC. Treatment of the Enlarged Clitoris. Front Pediatr 2017; 5. DOI: 10.3389/fped.2017.00125.

- Pippi Salle JL, Braga LP, Macedo N, Rosito N, Bagli D. Corporeal Sparing Dismembered Clitoroplasty: An Alternative Technique for Feminizing Genitoplasty. J Urol 2007; 178 (4s): 1796–1801. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.03.167.

- Guarino N, Scommegna S, Majore S, Rapone AM, Ungaro L, Morrone A, et al.. Vaginoplasty for Disorders of Sex Development. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2013; 4: 29, DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00029.

- Rink RC, Cain MP. Urogenital mobilization for urogenital sinus repair. BJU Int 2008; 102 (9): 1182–1197. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.08091.x.

- Looijenga LHJ, Hersmus R, Oosterhuis JW, Cools M, Drop SLS, Wolffenbuttel KP. Tumor risk in disorders of sex development (DSD). Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007; 21 (3): 480–495. DOI: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.05.001.

- Looijenga LHJ, Hersmus R, Leeuw BHCGM de, Stoop H, Cools M, Oosterhuis JW, et al.. Gonadal tumours and DSD. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010; 24 (2): 291–310. DOI: 10.1016/j.beem.2009.10.002.

- Finlayson C, Fritsch MK, Johnson EK, Rosoklija I, Gosiengfiao Y, Yerkes E, et al.. Presence of Germ Cells in Disorders of Sex Development: Implications for Fertility Potential and Preservation. J Urol 2017; 197 (3 Part 2): 937–943. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.108.

- Harris CJ, Corkum KS, Finlayson C, Rowell EE, Laronda MM, Reimann MB, et al.. Establishing an Institutional Gonadal Tissue Cryopreservation Protocol for Patients with Differences of Sex Development. J Urol 2020; 204 (5): 1054–1061. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000001128.

- Kaefer M, Diamond D, Hendren WH. The Incidence Of Intersexuality In Children With Cryptorchidism And Hypospadias: Stratification Based On Gonadal Palpability And Meatal Position. J Urol 1999; 162 (3 Part 2): 1006–1007. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)68049-2.

- Kim S, Rosoklija I, Johnson EK. Surgical, Patient, and Parental Considerations in the Management of Children with Differences of Sex Development. Curr Pediatr Rep 2018; 6 (3): 209–219. DOI: 10.1007/s40124-018-0177-4.

- Mouriquand PD, Gorduza DB, Gay CL. Re: “Surgery in disorders of sex development (DSD) with a gender issue: If (why), when, and how?” J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (6): 442–443. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.07.013.

- Nixon R, Cerqueira V, Kyriakou A, Lucas-Herald A, McNeilly J, McMillan M, et al.. Prevalence of endocrine and genetic abnormalities in boys evaluated systematically for a disorder of sex development. Hum Reprod 2017; 32 (10): 2130–2137. DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dex280.

- Van Batavia JP, Kolon TF. Fertility in disorders of sex development: A review. J Pediatr Urol 2016; 12 (6): 418–425. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.09.015.

Last updated: 2025-09-25 12:10