35: Foreskin Anomalies

This chapter will take approximately 15 minutes to read.

Embryology

The embryology of the external male genitalia is a complex process. Before the ninth week of gestation, the development of the external genitalia is similar in both sexes. During the 9 to 13 weeks of gestation, testosterone production by Leydig cells, its conversion to Dihydrotestosterone (5α-reductase enzyme) and interaction with androgen receptors will result in the normal differentiation of the genital tubercle, folds and swelling.

Androgen stimulation causes elongation of the genital tubercle as well as fusion of the urethral folds creating the urethra from proximal to distal. The prepuce forms between the 13th and 18th week of gestation overlapping with the development of the urethra. The preputial folds move from the base of the shaft distally until its fusion with the glans creating the midline raphae. Normal subsequent desquamation of the epithelial fusion between the glans and the prepuce will allow foreskin separation and future retraction.1

Phimosis

Phimosis is the inability to retract the prepuce exposing the glans. Physiologic phimosis exists because of natural adhesions between the inner preputial skin and the glans and in some cases because of the presence of a constrictive ring (Figure 1). Normal separation is produced by the normal accumulation of epithelial debris called smegma and intermittent erections during the first years of life.

Figure 1 Physiologic Phimosis in a 1-year-old boy.

Physiologic phimosis reduces with age: only 10% will remain with this condition by 3 years and less than 1% by 17 years of age. Primary phimosis commonly resolves spontaneously during childhood.1,2

It is important to differentiate phimosis from glandular adhesions (gland-preputial adhesions) which are attachments between the inner prepuce to the glans. They can also be secondary, traditionally after a circumcision, between the incision line and the glans. Physiologic adhesions will resolve spontaneously due to epithelial separation and erections during the childhood. In patients with asymptomatic preputial adhesions manual retraction should be avoided. Uncommonly, persistent adhesions in older patients can be lysed in the office after the application of topical analgesics.1,2

Secondary phimosis may result from different causes like forced and traumatic retractions with secondary scar formation or the presence of balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) (Figure 2). Prevention of secondary phimosis by avoiding forceful retraction should be advocated during the consult.

Figure 2 Balanitis Xeroticans obliterans.

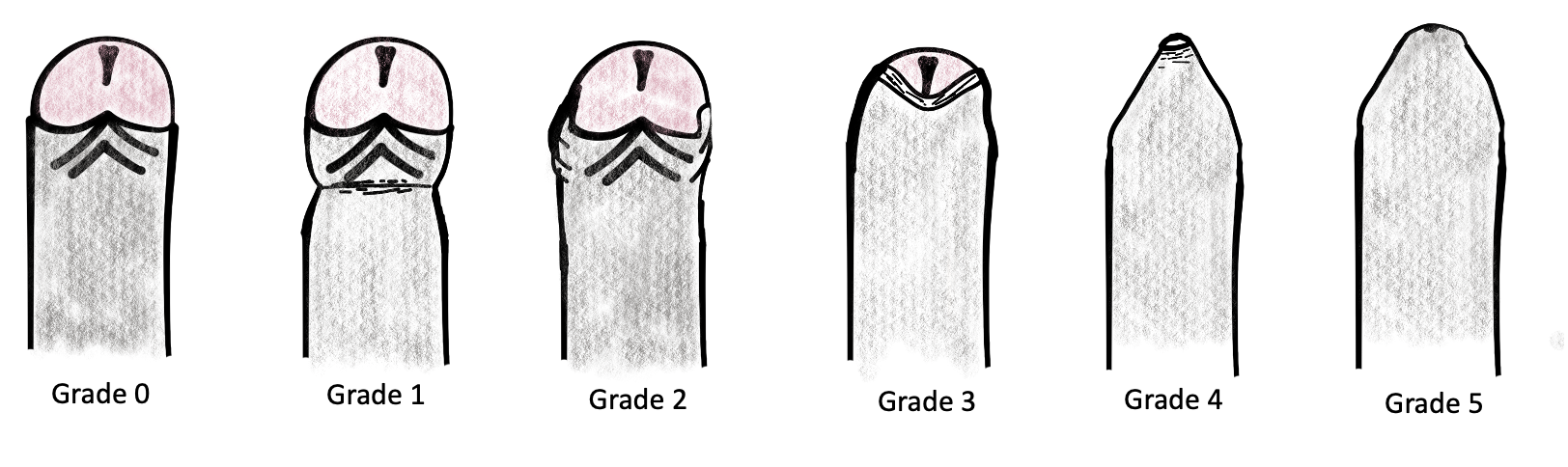

Different grading systems have been proposed to stratify the severity of the phimosis. One of them is the one proposed by Sookpotarom et al, which goes from a grade 0 with a complete and full retraction to a grade with no retraction (grade 5) (Figure 3).3

Figure 3 Phimosis retraction grading scale by Sookpotarom et al.

Conditions related with the uncircumcised penis are shown next.

Balanitis and Posthitis

These are inflammation process of the glans and foreskin, respectively, secondary to a poor hygiene in a phimotic patient. These conditions often occur simultaneously. A meticulous hygiene is the cornerstone of prevention. History of these episodes should encourage an enhanced preputial management.

Paraphimosis

It is the entrapment of the prepuce behind the glans, producing pain, swelling, edema and even necrosis of the foreskin if it is not reduced in time (See later paraphimosis).

UTI

Phimosis causes inner preputial skin and perimeatal colonization by uropathogens increasing the risk of UTI. Circumcision reduces this risk of UTI, with a relative risk of 4.5 in uncircumcised versus circumcised infants < 1 month of age, and relative risk of 3.7 during the first year of life. Calculated number to treat is more than 100 to prevent one UTI, but this number reduces to 4 in boys with dilated vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) (grade 3–5). Patients with more severe phimosis have also an increased prevalence of UTI compared with patients with mild grade of phimosis.4,5 Circumcision should be considered as an option in patients with VUR to reduce the risk of UTI by the American Urological Association.4

Cancer

Phimosis has been described as a significant risk factor for penile carcinoma.1

Treatment

In asymptomatic patients with physiologic phimosis active management should start after 2-3 years of age or according to the caregiver preference.2 Medical or surgical management of phimosis should be encouraged in some situations like: posthitis, balanitis, secondary phimosis, BXO or recurrent UTIs.

Medical Treatment with Topical Corticosteroids

Combined preputial management with the use of topical corticosteroid and manual retraction has shown high rate of success.2 Betamethasone cream (0.05%) is one of the most frequently used topical treatment in symptomatic or persistent primary phimosis with no pathologic changes of the prepuce. The physiologic mechanism is believed to be secondary to improvement in the preputial skin elasticity.

The European Urological Association recommends the use of topical corticosteroids in case of physiologic phimosis persistence with an 80% success rate and a 17% recurrence rate.2 The most common protocol is ointment administration twice a day for a minimum period of 4 to 8 weeks.

Neonatal Circumcision

Elective circumcision during the neonatal period is a controversial topic of discussion. The American Academics of Pediatrics, in the Task Force published in 2012, emphasized that routine circumcision should not be recommended for all male newborn, but the benefits are sufficient to justify the access to this procedure for families who consider it.1

One of the most important points when this kind of circumcision is performed is the analgesia and local anesthesia. Different options are recommended like topical anesthetic, dorsal penile nerve block or a penile ring block. Several techniques and devices have been developed to facilitate this procedure like the Gomco Clamp, the Mogen Clamp and the Plastibell device.

It is imperative not to perform neonatal circumcision in patients with other urological conditions that will require an intact prepuce for their surgical correction in the future, as hypospadias. In order to exclude these kinds of anomalies, proper genital examination with a complete separation of the prepuce from the glans should be performed before the procedure.

Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans

BXO (also named as lichen sclerosus) is a chronic inflammatory disease which can affect the foreskin, glans and urethra. The name derives from the three components of the disease, which are balanitis (chronic inflammation of the glans penis), xerotic (abnormally dry appearance of the lesion) and obliterans (association of occasional endarteritis).6

The reported incidence is 0.4 cases/1000 boys per year and the published prevalence of BXO in phimotic patients varies between 9 and 50%. The average age at presentation has been reported to be 8.9 - 10.6 years with a peak incidence between 9 and 11 years of age.7,8,9

In a recent publication by Filho et al, BXO was diagnosed histologically in 32% of phimotic patients with no clinical suspected BXO after circumcision. The degree of phimosis was no correlated with the presence of BXO.7,9

The diagnosis is mostly clinical. In mild cases with BXO, areas of greyish white discoloration on the glans or the inner layer of the foreskin can be found (Figure 2). As this condition progresses, the skin becomes inelastic with whitish discoloured plaques along with progressive fibrous phimosis. In more severe cases, ulceration and involvement of the meatus and urethra can be found.6,9

Most pediatric patients are asymptomatic but some of them described dysuria or episodes of urinary retention and prepuce ballooning. The diagnosis is confirmed via histology revealing hyperkeratosis and atrophy of the basal layer of the epidermis with loss of elastic fibbers and collagen alterations with inflammatory infiltration.

Etiology of this disease is still unknown. There is evidence that supports an underlying autoimmune mechanism. The lesions are histologically characterized by an abundance of infiltrating, auto reactive cytotoxic T lymphocytes and impaired metabolism of extracellular matrix. Also, autoantibodies to extracellular matrix protein have been detected in serum of affected patients. Infectious causes, genetic predisposition, chronic irritation through urine exposure and hormonal influences are other postulated theories.6

BXO Management

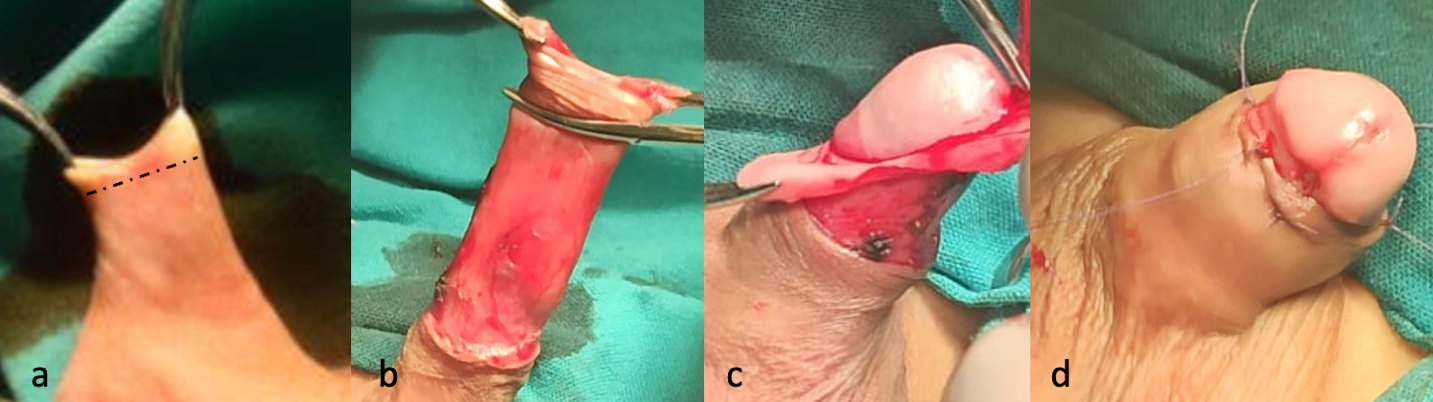

The most accepted and recommended treatment for BXO is circumcision which can be a definitive treatment in many cases (Figure 4). However, a significant number of centres are performing foreskin conservative surgery such as a preputioplasty, as a less aggressive surgical option. Wilkinson et al reported their results comparing boys with BXO treated with preputioplasty combined with injections of triamcinolone in the lesions intraoperatively against those ones treated with circumcision. During the follow up, 19% of circumcised boys required subsequent meatal surgery, compared to 6% of those who underwent preputioplasty. The success rate of the conservative surgery reported was 81%.10 Recently Green et al published a similar study comparing circumcision and preputioplasty in patients with BXO reporting no significant difference in meatal adjunct procedure rate, re-intervention rate postoperative infection or secondary haemorrhage between preputioplasty and circumcision group of patients. They conclude that preputioplasty with intralesional steroids may be a valid first-line operative treatment for BXO.11

Figure 4 Surgical circumcision: (a) Skin incision is performed under the phimotic ring (b) Inner prepuce dissected from the outer prepuce (c) Excision of inner prepuce leaving a 5 mm mucosal collar (d) Suturing between the mucosal collar and skin with resorbable suture.

A systematic review done by Folaranmi addressing the proposal of topical corticosteroid as an alternative to circumcision found that the average success rate of response was 35% for topical treatment in patients with BXO. The only prospective double blind randomized controlled trial that was included in this review demonstrated that no single patient with BXO responded to topical corticosteroids and all required circumcision.9

Use of topic immunosuppressant such as tacrolimus has also been described. Ebert et al reported that application of tacrolimus 0.1% ointment after circumcision resulted in recurrence in 9%, which was successfully treated with a new cycle of the drug. They conclude that this therapy is an option after surgery if there is a risk of complicated outcome caused by meatal or glandular involvement.6

When meatal involvement with BXO is detected, an endoscopy should be performed to determine the extension of the inflammatory process. A meatoplasty combined with topical corticoids or immunosuppressants is mandatory in these cases.

In some patients, especially with history of recurrent meatal stenosis or poor response with the local treatment, reconstructive surgeries using buccal mucosa graft should be considered.6

Complications

The complication rate of circumcision has been reported between 0.2% to 5%. Complications can occur immediately after the procedure or many years later. The most frequent complication described is bleeding which is more common in older children. Although compression will be effective for control this complication in most of the cases, cauterization might be needed in a few of them (Figure 5).1

Figure 5 Postoperative hematoma. Bleeding is the most common complication after circumcision.

Excessive skin removal after circumcision can produced a trapped penis from a cicatricial scar. It can be treated with betamethasone in conjunction with manual retraction as a first option. In some cases, relaxation incisions or formal repair with skin flaps might be necessary.

Meatal stenosis almost only occurs in patients after circumcision, and it is consequence of a local inflammatory reaction and cicatrix formation. Patients with a suspected meatal stenosis can complain of penile pain at the beginning of the micturition and/or a narrow urinary stream.

Paraphimosis

Paraphimosis is a urological emergency which affects uncircumcised males where the penile foreskin is retracted behind the coronal sulcus resulting in strangulation of the glans (Figure 6). If it is not reduced in time, the retracted foreskin can cause preputial and glans edema, venous congestion, and finally necrosis and gangrene of the glans. This condition may occur at any age, but it is more common among adolescents with a reported incidence of 0.7% in uncircumcised boys.12,13,14

Figure 6 Paraphimosis.

Management consists in reducing penile and glans edema followed by retracting the foreskin back over the glans to its anatomical position. Before attempting any manoeuvre, it is very important to achieve adequate analgesia. Local anaesthetics commonly utilized are 2% lidocaine gel or EMLA cream (2.5% lidocaine and 2.5% prilocaine). Oral or intravenous narcotics can be used in combination topical anaesthetics to achieve optimal pain control.

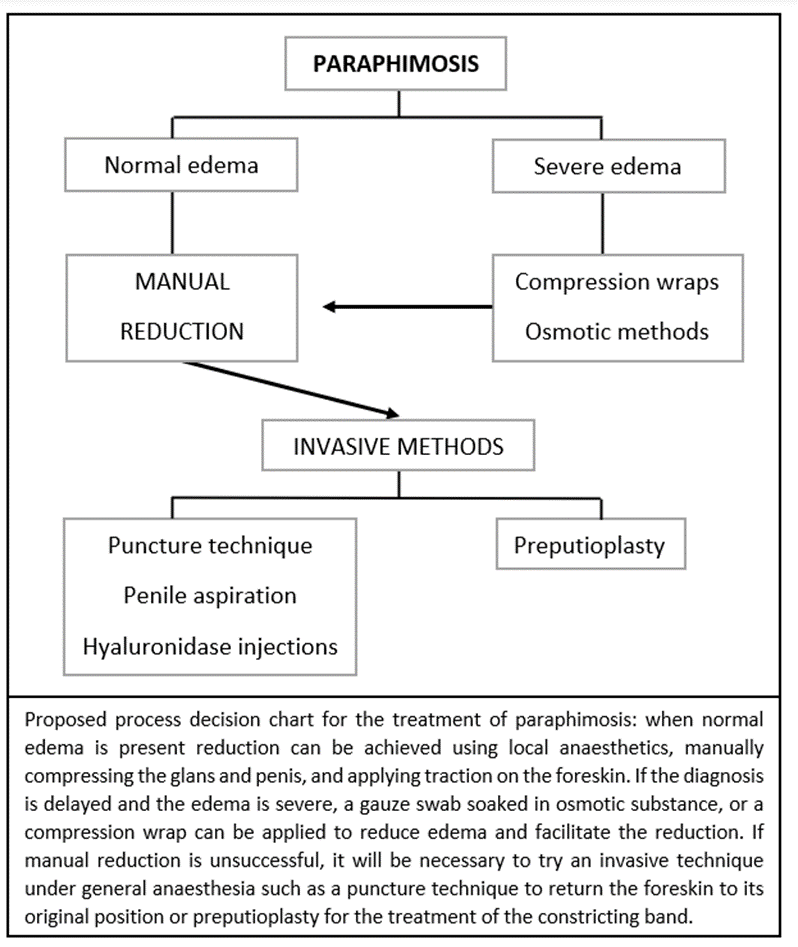

Several non-invasive techniques have been described to reduce paraphimosis. When conservative measures fail, more invasive methods can be employed (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Paraphimosis management algorithm.

Non-invasive techniques:

- Manual reduction: First, circumferential pressure is applied with a gloved hand to the distal part of the penis for several minutes to reduce swelling. After a few minutes of compression, both thumbs are placed compressing on the glans, while counter-traction is applied on the foreskin just proximal to the tight constrictive band. This technique can be facilitated by applying ice over the zone some minutes before the maneuver is started.

- Compression wraps: a flexible self-adhering bandage is wrapped around the penis starting at the glans and removed after 5 to 20 min. The wrap generates constant gentle pressure pushing fluid proximally back underneath the tight constrictive band of tissue. If spontaneous reduction does not occur, gentle manual reduction can be employed.

- Osmotic methods: a substance with a high solute concentration is used on the surface of the penis and foreskin reducing the edema of the tissues and facilitating the reduction. Soaked gauzes are wrapped around the edematous prepuce, with minimal intermittent hand compression for 1 to 2 hours. Several substances have been used for osmotic reduction of paraphimosis: glycerine magnesium sulphate, granulated sugar, 50% dextrose solution and 20% Mannitol solution.

Invasive methods:

- Puncture technique: A 26-gauge needle is used to make approximately 20 puncture holes in the prepuce reducing edema to permit reduction.15,16

- Penile Aspiration: a tourniquet is applied in the shaft of the penis and then a 20-gauge needle is inserted parallel to the urethra to aspirate 3 to 12 ml of blood from the glans. This procedure reduces the volume of the glans to facilitate manual reduction.16

- Hyaluronidase injections: 1 ml of 150 units/mL of hyaluronidase is injected through 2 or 3 sites into the prepuce. Hyaluronidase breaks down the viscous hyaluronic acid in the extracellular fluid and facilitates dissipation of edema so the foreskin can then be gently retracted over the glans.

- Preputioplasty: the constricting band is identified and a 1–2 cm dorsal longitudinal incision is performed. Release of the constricting band permits reduction of glandular edema so the foreskin can be reduced. The incision is then sutured in a transverse fashion with non-continuous reabsorbable sutures (Figure 8).15,17

Figure 8 Preputioplasty.

Inconspicuous Penis

It is a penile anomaly where a penis with a normal length (from the tip of the glans to the pubis) and shaft diameter, appears smaller. Different entities are included in this definition as buried penis, trapped penis or webbed penis.1,18

Buried Penis

It is a normal penis hidden by the suprapubic fat pad. It is also called concealed or hidden penis

Several different categories have been described according to the cause of concealing:

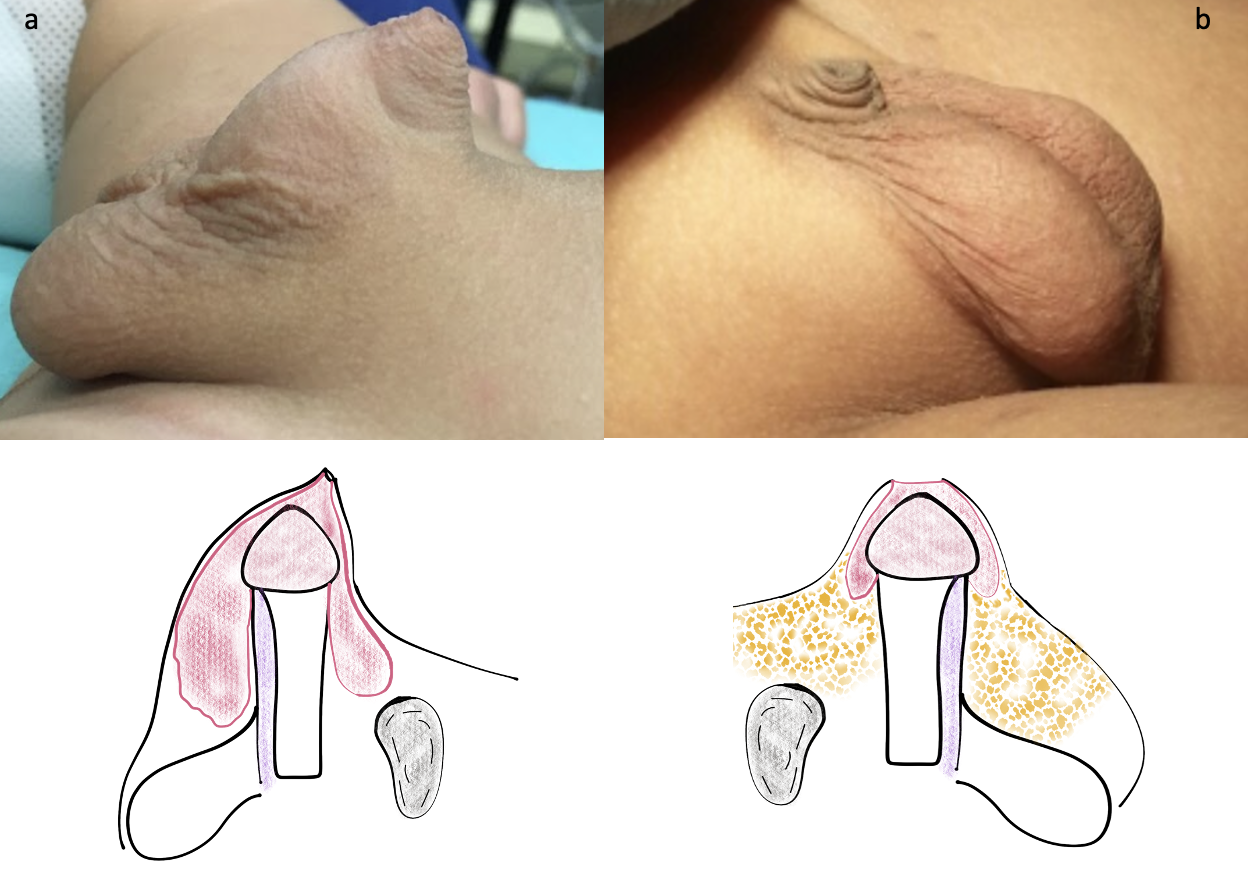

- A congenital form with a lack of fixation between the skin and the base of the penis resulting in tenting. Its embryological origin is believed to be secondary from a failure of separation of the migrational planes during the development of the male external genitalia. This anomaly results in penile corporal tethered to the deep fascia and the scrotum located high in the groin (Figure 9).

- Two different sub-categories can be easily identified based on the presence or not of megaprepuce which is an association of a phimotic ring with a major ballooning of the inner prepuce during micturition (Figure 10). This phenomenon can cause some degree of discomfort to the patient. The hemispheric tumefaction is also named as preputial bladder and it is usually diagnosed by the parents during the first months of life who need to compress it manually to allow the exit of the urine through the phimotic orifice.

- An acquired form due to obesity (Figure 9). This one should be differentiated from the transient form in the early childhood that resolves with increased age and deambulation

- A cicatrized form secondary to penile surgeries like circumcision.

Figure 9 Different forms of buried penis: (a) Congenital with megaprepuce (b) Secondary to obesity

An important step in the physical examination is to differentiate this entity from a true micropenis which has an abnormal stretched penile length.

Figure 10 Megaprepuce with ballooning of the inner prepuce during micturition.

Management

In patients with buried penis secondary to obesity, treatment should be first focused in losing weight with a diet and exercise program provided by the primary care provider.

Physiologic or secondary phimosis in symptomatic patients with this condition should be actively managed with topical corticosteroids and manual traction. In those patients where this treatment is ineffective, an elective repair should be planned by the age of 6 months or older.

Standard circumcision should be avoided in this group of patients because of the poor cosmesis and the need of further procedures in the future.

Various surgical correction techniques of this malformation have been described, all of them with the same goals:

- To remove the stenotic preputial ring relieving voiding symptoms

- To restore the penopubic and penoscrotal angles

The main difference between these techniques results in how to cover the penile shaft skin deficiency which is a common feature in these patients.

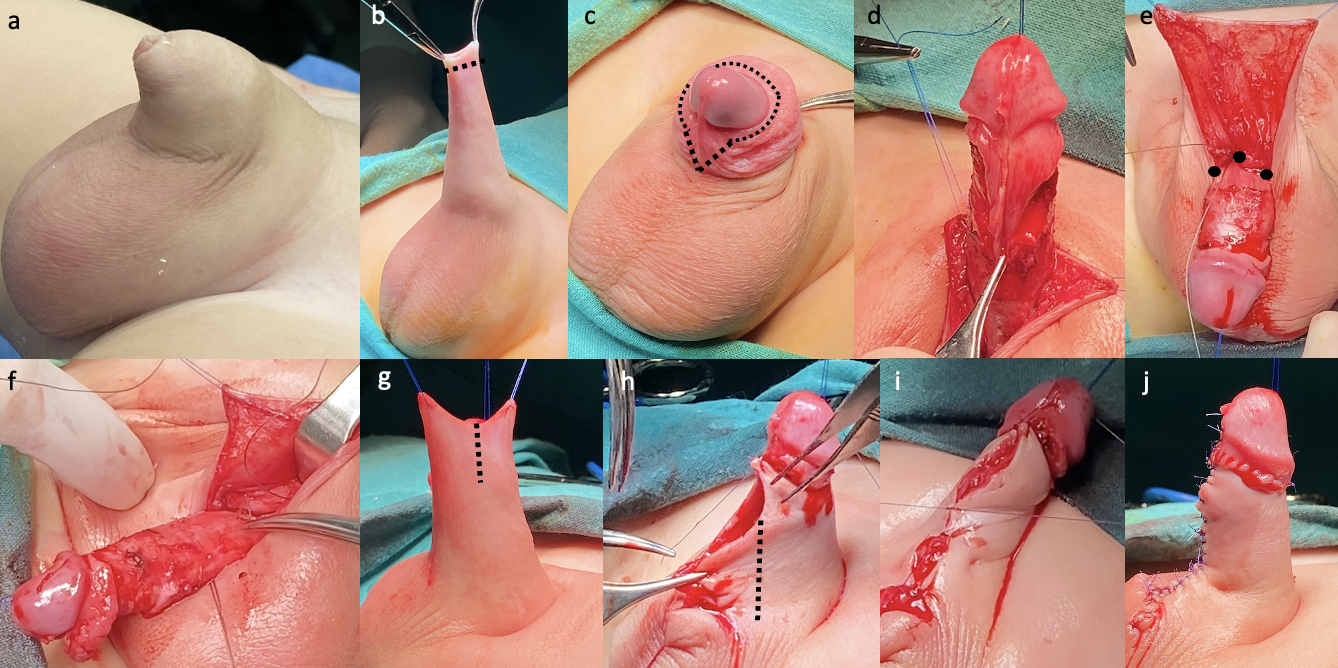

Surgical techniques using penile skin (Figure 11):

- Dorsal neurovascular bundle infiltration or caudal blocking with bupivacaine is performed depending on the anesthesiologist and surgeon preference.

- The first step is retraction of the skin which can be obtained with a limited circumferential incision at the narrow ring of the outer prepuce (Figure 11 b).

- A traction suture is placed on the glans to facilitate the dissection.

- The preputial skin and Dartos’s tunica are dissected off the Bucks’s fascia freeing the penile shaft from its abnormal attachments.

- A vertical incision is made in the ventral part of the preputial skin allowing a better exposure and dissection at the base of the penis near to the pubic bones.

- The inner prepuce is resected completely leaving only a 5 mm mucosal cuff under the glans (Figure 11 c-d).

- One of the most important steps is to use at least 3 anchoring sutures (at 3, 9 and 12 o’clock positions) between the skin and the Buck’s fascia to create the penopubic angle. We prefer non absorbable sutures like Polypropylene 5-0.

- A Ventral transverse incision at the level of the penoscrotal junction allows the scrotal skin to be mobilized caudally and reconfigure the penoscrotal angle after is closed in a vertical way (Figure 12 h-i).

- A compression dressing is left for a week to prevent wound edema and bleeding.

- In the anatomical approach described by Smeulders et al, a longitudinal ventral and a curved incision in the penoscrotal limit line are made. Then a deep dissection of the penis close to Buck’s fascia is carried out and the redundant inner prepuce is removed close to the sulcus. A dorsal quadrilateral skin flap is thinned and anchored to the Buck’s fascia and then wrapped around the penis and sutured to the mucosal cuff. The ventral incision is sutured in a transverse way creating the penoscrotal angle.19

Figure 11 Surgical reconstruction technique of buried penis with megaprepuce using penile skin: (b) Outer prepuce skin incision and retraction of the phimotic prepuce (c-d) Excision of the inner prepuce (a V shaped ventral mucosa is left in place for an eventual skin defincency) (e-f) Anchoring non-absorbable sutures (at 3, 9 and 12 o’clock) creating penopubic angle (g) Dorsal skin Byars flap are used to wrap the penis shaft (h-i) Ventral incision is performed to create penoscrotal angle (j) Final appearance.

Surgical Techniques Using the Inner Prepuce

The concept of covering the shaft with the inner prepuce was first described by Donahue and Keating in 1986. The unfurling techniques facilities the reconstruction without tension using the redundant inner prepuce which will acquire a foreskin appearance in the future.

In the publication by Ruiz et al, a simplified approach of this malformation was proposed. Using Donahue’s inner prepuce concept, a fixation of the outer prepuce to the Buck’s fascia is created and the unfurled and tailored inner prepuce is used to cover the penile shaft.20

On the other hand, Rod et al highlights the importance of reducing the inner prepuce in length and circumference to avoid an unesthetic appearance. They also described the importance of removing the subcutaneous tissue of the inner prepuce to reduce the probability of local lymphedema.21

The ventral V plasty is a combined technique where a V shaped incision is performed in the ventral inner preputial layer. This preputial layer will be leaved in place to be interposed and facilitate the skin closure in the ventral part of the shaft (Figure 12).18

Figure 12 Ventral V plasty in an older patient with a severe ventral skin deficiency.

A two staged approach was also proposed, where a first limited preputioplasty is performed to relieve the urinary flow obstruction. This approach preserves the preputial skin and allows physiologic remodeling while the patient grows. If a second procedure is needed, it will be scheduled after toilet training.

Webbed Penis

It is a congenital condition where the scrotal skin extends to the ventral part of the penis. It is also called penoscrotal fusion. It is asymptomatic and produces an abnormal appearance of the ventral surface of the penis.

The surgical correction consists in a transversal skin incision on the web, creating a separation between the penis and the scrotum which is closed in a vertical fashion.1,18

[Video 1](#video-1){:.video-link}. Surgical repair Buried penis

References

- L. P, J P. Management of abnormalities of the external genitalia in boys. 44: 871–904 10. DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4160-6911-9.00131-6.

- Hoen LA ’t, Bogaert G, Radmayr C, Dogan HS, Nijman RJM, Quaedackers J, et al.. Update of the EAU/ESPU guidelines on urinary tract infections in children. Eur Urol 2021; 79: S446–s448. DOI: 10.1016/s0302-2838(21)00695-3.

- Sookpotarom P, Asawutmangkul C, Srinithiwat B, Leethochawalit S, Vejchapipat P. Is half strength of 0.05 % betamethasone valerate cream still effective in the treatment of phimosis in young children? Pediatr Surg Int 2013; 29 (4): 393–396. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-012-3253-9.

- AUA Practice Guidelines Committee. Management and Screening of Primary Vesicoureteral Reflux in Children. 2017.

- Holzman SA, Chamberlin JD, Davis-Dao CA, Le DT, Delgado VA, Macaraeg AM, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Retractable foreskin reduces urinary tract infections in infant boys with vesicoureteral reflux. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2021; 7 (2): 09 1–209 6. DOI: 10.3410/f.739509971.793583981.

- Celis S, Reed F, Murphy F, Adams S, Gillick J, Abdelhafeez AH, et al.. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and adolescents: a literature review and clinical series. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2014; 0 (1): 4–9. DOI: 10.3410/f.718196548.793513188.

- Aziz Filho AM, Azevedo LMS de, Rochael MC, Jesus LE de. Frequency of lichen sclerosus in children presenting with phimosis: A systematic histological study. J Pediatr Urol 2022; 18 (4): 529.e1–529.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2022.06.030.

- Jayakumar S, Antao B, Bevington O, Furness P, Ninan GK. Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and its incidence under the age of 5 years. J Pediatr Urol 2012; 8 (3): 272–275. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.05.001.

- Folaranmi SE, Corbett HJ, Losty PD. Does application of topical steroids for lichen sclerosus (balanitis xerotica obliterans) affect the rate of circumcision? A systematic review. J Pediatr Surg 2018; 53 (11): 2225–2227. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.12.021.

- Chapple C, Osman N. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Foreskin preputioplasty and intralesional triamcinolone: a valid alternative to circumcision for balanitis xerotica obliterans. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2012; 7 (4): 56–59. DOI: 10.3410/f.724694941.793513186.

- Green PA, Bethell GS, Wilkinson DJ, Kenny SE, Corbett HJ. Surgical management of genitourinary lichen sclerosus et atrophicus in boys in England: A 10-year review of practices and outcomes. J Pediatr Urol 2019; 15 (1): 45.e1–45.e5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2018.02.027.

- Burstein B, Paquin R. Comparison of outcomes for pediatric paraphimosis reduction using topical anesthetic versus intravenous procedural sedation. Am J Emerg Med 2017; 35 (10): 1391–1395. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.04.015.

- Pohlman GD, Phillips JM, Wilcox DT. Simple method of paraphimosis reduction revisited: Point of technique and review of the literature. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (1): 104–107. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.06.012.

- Barberan Parraga C, Peng Y, Cen E, Dove D, Fassassi C, Davis A, et al.. Paraphimosis Pain Treatment with Nebulized Ketamine in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med 2022; 62 (3): e57–e59. DOI: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.12.011.

- Little B, White M. Treatment options for paraphimosis. Int J Clin Pract 2005; 59 (5): 591–593. DOI: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2004.00356.x.

- Anand A, Kapoor S. Mannitol for Paraphimosis Reduction. Urol Int 2013; 90 (1): 106–108. DOI: 10.1159/000343737.

- DeVries CR, Miller AK, Packer MG. Reduction of paraphimosis with hyaluronidase. Urology 1996; 48 (3): 464–465. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(96)00198-7.

- Shalaby M, Cascio S. Megaprepuce: a systematic review of a rare condition with a controversial surgical management. Pediatr Surg Int 2021; 37 (6): 815–825. DOI: 10.1007/s00383-021-04883-5.

- Smeulders N, Wilcox DT, Cuckow PM. The buried penis - an anatomical approach. BJU Int 2000; 86 (4): 523–526. DOI: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00752.x.

- Ruiz E, Vagni R, Apostolo C, Moldes J, Rodríguez H, Ormaechea M, et al.. Simplified Surgical Approach to Congenital Megaprepuce: Fixing, Unfurling and Tailoring Revisited. J Urol 2011; 185 (6s): 2487–2490. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.015.

- Rod J, Desmonts A, Petit T, Ravasse P. Congenital megaprepuce: A 12-year experience (52 cases) of this specific form of buried penis. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (6): 784–788. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.10.010.

Last updated: 2025-09-25 12:10