6: General Anesthesia Considerations In Children

This chapter will take approximately 27 minutes to read.

Introduction

Pediatric urology procedures cover a wide range of patient types, surgical approaches, and a broad spectrum of anesthetic requirements and approaches. Anesthesia plans may vary to include anesthesia for same-day outpatient surgery procedures in healthy patients with an isolated urologic concern or they may be more involved and complex.

Anesthesia in medically complex patients or those involving multiple stages of surgical intervention may include multimodal analgesia, various neuraxial or regional anesthetic block techniques in addition to general anesthesia and may require inpatient stays where postoperative acute pain services can be provided. Medically complex patients may benefit from a visit to the pre-anesthesia or pre-surgical optimization clinic to ensure that all follow-up information is up to date (e.g., echocardiogram and cardiology clearance in patients with congenital heart disease) and to allow for timely completion of any necessary laboratory work or imaging.

Good pre-operative communication between the surgical and anesthesia teams is ideal and may include any special peri-operative needs, anticipated post-operative admission or pain issues.

Parents may have accessed information regarding anesthesia online or they may have questions for the urologist regarding anesthetics. These parents can typically be reassured that they will speak to an anesthesia provider on the day of surgery, or they can be provided with the anesthesia group’s contact information for further questions.

Preoperative Assessment

Anxiolysis

Preoperative anxiety in children can result in significant morbidity and postoperative behavior changes. Data from the US and Europe have shown that up to 54% of patients will exhibit general anxiety, nightmares, nighttime crying, enuresis, separation anxiety, and temper tantrums for 2 weeks after their surgical procedure. Some children continue to have maladaptive behavior changes 6 months to a 1 year after their procedure. The quality of their medical experience is crucial in limiting postoperative behavior changes and decreasing anxiety in subsequent visits. Several methods are available to help decrease patients’ preoperative anxiety and improve their perioperative experience.1

Both pharmacologic agents and distraction technologies can be effective in anxious children.2 Separation anxiety begins around the age of 1 year. Situational anxiety peaks in the preschool- age child. Therefore, we administer an oral anxiolytic (such as midazolam oral liquid, 0.5–0.75 mg/kg) in the pre-operative holding area 15–30 minutes prior to inhalational anesthesia induction to allow optimal timing of medication effect. Intranasal and intramuscular delivery of pharmacologic agents are other options for anxiolytic administration.

Developmentally normal children are generally able to sit for an intravenous (IV) catheter placement in pre-operative holding at our institution after the age of 7 years, so it is more typical to offer an IV induction for older children, though inhalational induction may still be more feasible in certain patients. Child life specialists (persons trained to provide distraction and reassurance to children during medical visits) are available to teach coping skills, provide play, description of induction process and assist with IV placement. Additional devices may be used, such as jet-delivered buffered lidocaine (creates a wheal of numb skin using pressurized lidocaine and no needle) through which the IV catheter can be inserted, causing minimal pain. Topical anesthetics may also be applied to the skin, if timing allows, for reducing the pain of IV placement.3

Parental presence for induction can also help decrease anxiety and increase parental satisfaction. Some parents may prefer to be present regardless of the age of their child. Certain patient populations, such as those with a diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder, sometimes do better when familiar individuals such as parents or care providers are present. Although parental presence for induction may be appropriate, studies have shown that pharmacologic premedication to treat anxiety is superior to parental presence for induction. A highly anxious parent or those with disruptive behaviors can hinder the induction process. Furthermore, parental presence for induction does not affect postoperative behavior changes, whereas oral midazolam has been shown to decrease immediate negative postoperative behavior outcomes in young children. The final decision to invite parents back to the operating suite should be made by the anesthesia team after the preoperative interview and a discussion of the anesthetic plan. Generally, parental presence for induction has been discouraged during the current pandemic except in very special circumstances.1

Acute Illnesses

Communicable Illnesses

- Delay elective procedures to avoid infecting others with communicable diseases.

- Chicken pox: no longer communicable once all skin lesions have crusted over.4,5

- Hand-Foot-Mouth disease: no longer communicable 3 weeks following resolution of rash.5,6

Respiratory Infections

A common conundrum in pediatric anesthesia practice is anesthetizing the well versus the unwell child. Certain pathogens and the subsequent reactivity of the airway mucosa can lead to complications with anesthesia. Following a cold with a cough, or uncomplicated upper airway infection (URI), airway reactivity may remain elevated for weeks. It is our policy to postpone elective procedures until four weeks after full resolution of symptoms of URI, or 6 weeks after symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection (LRI), such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), influenza, or pneumonia. This allows airway reactivity to return to baseline and reduces the risk of intraoperative anesthesia complications such as bronchospasm, laryngospasm, hypoxia, and unplanned post-operative admission.7,8

Generally, symptoms of URI and LRI are identified during the pre-operative screening phone call and cases can be cancelled with adequate time to fill the gap in the surgical schedule. But what should be done with the patient who is currently presenting for their case in pre-operative holding and who has “just” developed a runny nose, fever, cough, or a constellation of new symptoms? Certain aspects of a URI, such as green nasal discharge, wheezing on pulmonary auscultation, or fever within 48 hours, increase the relative risk of airway events enough to make day-of-surgery cancellation an easy decision.9 However, the case may not always be as clear-cut, with symptoms of an isolated clear rhinorrhea and occasional dry cough, for example. The patient may have had pre-operative testing; the parents may have taken the day off work; the child may be appropriately fasting; and day-of-surgery cancellations are inconvenient for everyone involved. It is our practice to assess each child on a case-by-case basis with safety as our primary goal, ruling out signs of florid illness such as active fever, and taking into account the urgency of the surgical procedure and any extenuating circumstances, such as when there has been a long distance traveled, or when child is frequently ill to the point where finding a four-week block of symptom-free recovery may be almost impossible, or when there is limited parental work leave to care for the child, which might make rescheduling the case particularly difficult. We also include parents in the decision-making process, letting them know that, although the overall absolute risk is low, anesthesia in the setting of an active upper respiratory infection may present more risk than in a well child. Risk stratification by symptom type and duration and patient risk factors such as passive smoke exposure, age, and asthma, is supported in the literature with general recommendations to proceed with mild symptoms in low-risk patients and reschedule for significant symptoms in those who are at higher risk.1

SARS-CoV-2

A retrospective cohort study at a large academic pediatric hospital revealed that each child with a positive SARS-CoV-2 test in the 10 days prior to a procedure had a much higher incidence of respiratory complications (11.8% vs 1.0%, 95% CI 1.6-19.8%, p = 0.003) when compared to matched controls. Given the additional infectivity risk to other patients in proximity and to medical staff, it is our recommendation to electively test every patient preoperatively for SARS-CoV-2 and to reschedule elective cases when there is a newly positive COVID-19 test.10

Asthma

Elective surgeries should be postponed until therapy for patients with poor control of symptoms has been optimized. Procedures for those with acute asthma exacerbations should be delayed for 4 weeks following resolution and return to baseline. Patients should consistently use their preventative asthma medications in the weeks and days prior to anesthesia.11,12

Medical Comorbidities

Depending on presentation of the disease state (acute, subacute, chronic) and the urgency of a surgical procedure, the pediatric urology patient may present in perfect health or with a spectrum of hemodynamic derangements, electrolyte imbalances, and organ dysfunction.

Patients with complex medical comorbidities should be seen in the preoperative clinic to ensure that medical conditions have been optimally controlled prior to surgery. Early referral to the preoperative clinic allows for sufficient time to effectively initiate an optimization program and to manage modifiable risks. Patients receiving maintenance medications for their chronic medical conditions should continue those medications in the perioperative period.13,14

Preoperative Fasting Guidelines

There are guidelines for reducing the risk of pulmonary aspiration in patients receiving medications that reduce protective airway reflexes. The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends that patients fast from fatty solid foods for 8 hours prior to surgery. Fasting recommendations for light meals, any non-clear beverage, non-human milk, and artificial enteral nutrition is 6 hours. Breast milk should be stopped for 4 hours, and clear liquids for 2 hours prior to anesthesia.15 The Canadian Anesthesiologists’ Society has similar guidelines, but the Canadian Pediatric Anesthesia Society now encourages children to have clear liquids up to one hour prior to surgery.16 The European Society of Anesthesiology fasting guidelines prohibit solid foods 6 hours prior to surgery and encourages adult patients to have clear liquids up to 2 hours and pediatric patients to have clear liquids up to 1 hour before surgery.17

There have been concerns that guidelines on clear liquids may be too rigid and may contribute to poor outcomes. Due to the unpredictability of surgical suites, a 2-hour clear liquid fasting in reality translates to a much longer fasting period. Prolonged fasting can increase discomfort and result in detrimental physiologic and metabolic effects. It is also difficult to enforce fasting guidelines for young children. Proponents of gastric ultrasounds have suggested that a measurement of gastric contents may be more reliable than fasting instructions alone. A gastric ultrasound should be obtained prior to cancellation or delay of a case due to NPO violation.

Anesthetic Considerations

General Versus Spinal Anesthesia

Application of Spinal Anesthesia

Spinal anesthesia is a good anesthetic option for patients undergoing procedures below the umbilicus.18 Technically speaking, there is no age limit for a spinal anesthetic. However, outside the neonatal and infant time frame a pure spinal anesthetic is unlikely to be successful without anxiolytics or sedation, given the patients’ cognitive development and inability to cooperate with spinal anesthetic placement and surgical procedure. Ex-premature infants often have a history of apnea of prematurity, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and chronic lung disease. Their risk for postoperative apnea is further increased compared to infants born at full term.19 When feasible, a spinal anesthetic would help decrease the potential risks associated with general anesthesia, such as neurotoxicity, apnea, and adverse cardiopulmonary events. Spinal anesthesia should be considered for patients in whom general anesthesia may pose an increased risk, such as those with facial dysmorphia, difficult airway, muscular dystrophy, or a family history of malignant hyperthermia.

Hemodynamic changes secondary to sympathectomy from a spinal or epidural anesthetic common in adults are not seen in young children. Children have relatively immature sympathetic nervous systems and are less dependent on vasomotor tone to maintain blood pressure. Furthermore, they have smaller venous capacitance in the lower extremity and thus less blood pooling.

Contraindications to Spinal Anesthesia

Spinal anesthesia is limited to surgeries lasting 90 minutes or less. Children have larger cerebrospinal fluid volume (CSF) and faster turnover of CSF compared to adults. Given this difference, spinal anesthesia typically lasts longer in older children and adults compared to neonates and infants. A single injection spinal anesthetic will typically last 60-90 minutes and may be extended to 120 minutes if done in combination with a caudal block.

Contraindications include coagulopathies, systemic infection, or local infection at site of puncture, uncorrected hypovolemia, parental refusal, and an uncooperative patient. Neurologic abnormalities such as spina bifida and increased intracranial pressure are also contraindications for spinal anesthesia.

Complications

Complications following spinal anesthesia include traumatic puncture leading to bleeding, pain and injury to the structures surrounding puncture site. With careful aseptic techniques the incidence of serious infectious complications such as meningitis is very low.20 Respiratory and cardiovascular insufficiency can result from a high spinal anesthetic. Neurologic injury and local anesthetic toxicity can result from injection of incorrect solution or dose of local anesthetic, respectively. Post-dural puncture headache is another complication of spinal anesthesia. However, the incidence of PDPH is unknown in younger children due to the difficulty in assessing headaches in that population.

Laparoscopic and Robotic Considerations

Robotic and laparoscopic urologic approaches are increasing.21 These approaches present unique changes to ventilation, venous return, hemodynamics, and abdominopelvic organ perfusion during the case. A general anesthetic with endotracheal intubation is required for these types of cases since awake patients cannot tolerate peritoneum insufflation. Furthermore, laparoscopic procedures typically require muscle relaxation to optimize surgical conditions. Pneumoperitoneum often contributes to a reversible oliguria or anuria and similar hemodynamic and respiratory changes as seen in adult laparoscopy.

Table 1 Physiologic changes in response to laparoscopy. CVP: central venous pressure; CO: cardiac output; MAP: mean arterial pressure; SVR: systemic vascular resistance; FRC, functional residual capacity; TLV, total lung volume; VTE, venous thromboembolism. Source: Miller RD et al. Miller’s Anesthesia 7e. Ch: Anesthesia for Laparoscopic Surgery (Ch. 68) pages 2185-2193.22

| Organ system | Intervention | Effects | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Head down position | Increased CVP, increased CO | Reduce tilt |

| Head up position | Decreased CVP, MAP | Reduce tilt | |

| Insufflation | Baroreceptor reflex → reflex bradycardia or asystole | Reduce or cease insufflation, treat heart rate | |

| Increased SVR | Reduce head-up tilt, use of vasodilators, deepen anesthetic | ||

| Respiratory | Insufflation, head down positioning | Atelectasis → decreased FRC, TLV, pulmonary compliance → hypoxemia, hypercarbia | Increase ventilatory parameters, decrease insufflating pressures, reduce head-down tilt |

| Neuro | Head down positioning | Elevated cerebral, intraocular pressures in patients with low intracranial compliance | Reduce downward tilt |

| Renal | Insufflation | Oliguria, anuria | Typically reversible and transient once insufflation released |

| Endocrine | Insufflation | Elevated catecholamines, stress hormones | Deepen anesthetic, adequately treat painful stimuli |

| Vascular | Positioning (especially lithotomy) and insufflation | Venous pooling in legs → increased risk of VTE | Use of anti-VTE devices, periodic changes in positioning |

Regional Anesthesia

Epidural Single Injections

Caudal anesthesia is a well-established technique with a long history of safety (Polaner et al—PRAN study). The benefits of a caudal anesthetic include decreased need for intraoperative and postoperative pain medications, decreased stress hormone response and increased overall patient and parental satisfaction.23

Caudal blocks are an injection of local anesthetic into the epidural space accessed via the sacral hiatus. The bony landmarks of the hiatus are generally palpable in young pediatric patients or visualized using ultrasound.

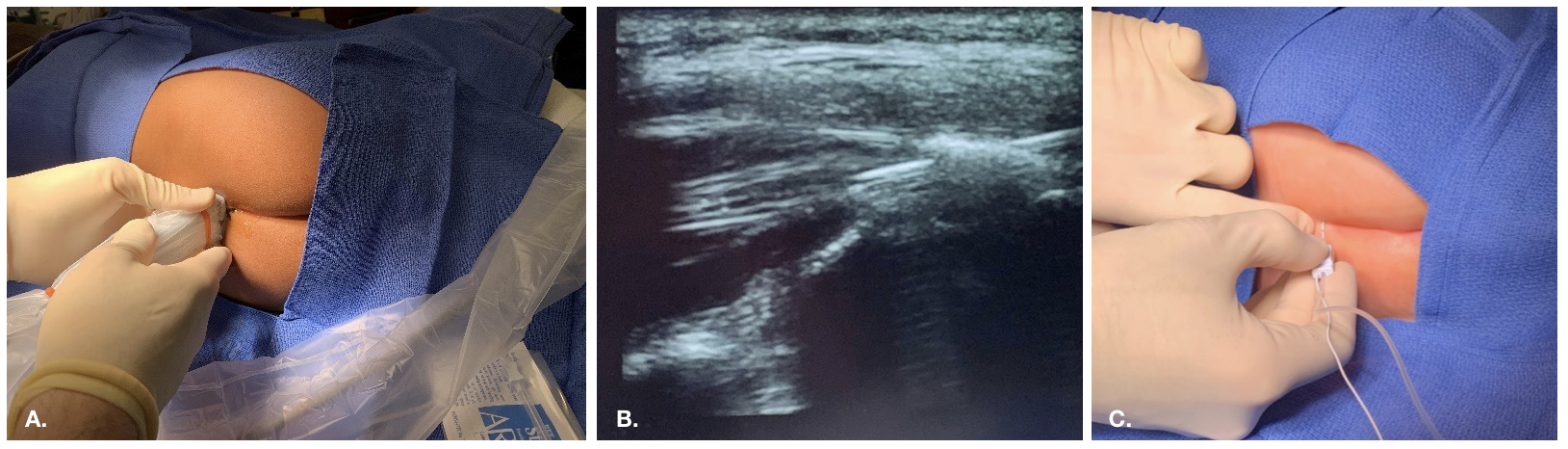

Figure 1 Anatomic approach to caudal block using palpation of bony landmarks. Palpation of bony landmarks while using an anatomic approach. External anatomy: sacral cornua and sacral hiatus.

Figure 2 Ultrasound guided approach to caudal block

Figure 3 Fluoroscopic guided epidural placement in a patient with challenging anatomical and post-surgical changes

Contraindications to Caudal Blockade

Contraindications include spinal dysraphism (e.g., tethered cord), infection at injection site or pilonidal cyst, patient refusal, and (relative) increased risk of bleeding.

Caudal blocks, while generally straightforward, uncomplicated, and successful, are associated with a certain failure rate, even in experienced hands. Failure most often occurs due to inappropriate anatomic location of injectate (e.g., subcutaneous, intravascular), which may initially go unrecognized.

Caudal Block Complications

Risks include bleeding, infection, nerve damage, inadvertent dural puncture and post-dural puncture headache, allergic reaction, and local anesthetic toxicity. The most common adverse event is the inability to place a block or block failure.20

Age Limit

While some centers limit caudal blocks to non-ambulatory (infant) populations, caudal blocks can be safe and effective in older children as well. In our pediatric practice, we often perform caudal blocks on older children, depending on habitus, for surgeries in which a sacral level of pain control is desirable (e.g., circumcision). In larger (over 50 kg) or older children, an at-level single shot lumbar epidural is generally straightforward but may exhibit sacral sparing due to the relatively large sacral nerve roots, and is thus more ideally suited for a lumbar level of analgesia (e.g., for a Pfannenstiel incision).2,24 Adult studies suggest a higher-than-expected rate of accidental intravascular injection when confirmatory caudal epidurography is performed.25 Anatomic changes to habitus, ossification of the sacrococcygeal membrane, and changes in the epidural space may also lead to a preferred access point at the lumbar or thoracic spine for neuraxial blocks in older, larger children and adults.

Hypospadias Rate of Complications

Hypospadias repair is a common urologic procedure in young males. Published reports have primarily looked at the impact of surgical techniques and severity of defects on the incidence of surgical complications. In recent years, there have been controversial reports on the effect of anesthetic technique on the rate of postsurgical complications such as urethrocutaneous fistula or glanular dehiscence.

In a randomized study comparing the efficacy of penile block and caudal anesthesia for hypospadias repairs, Kundra et al incidentally noted an increased incidence of urethrocutaneous fistula in patients who received a caudal block.26 It is important to note the small N of 54, and that the children in this study were age 4 to 12 years; older than the contemporary recommended age for hypospadias repair. Some studies have found older patient age as a risk factor for complications.27,28 Furthermore, surgery was performed by both urology and plastic surgeons and surgical techniques were different in the caudal block group compared to penile block group.

Taicher et al., in a review of primary hypospadias repairs performed by a single surgeon from 2001-2014, found that complications were associated with caudal blocks, proximal hypospadias, increased surgical duration, and surgeon’s earlier year of practice.29 After adjusting for confounders through multivariate logistic regression analysis, they concluded that both caudal blocks and proximal hypospadias remained highly associated with postoperative complications. The authors did note the routine use of lidocaine with epinephrine by their surgeon during all but the minimal glanular cases. However, since the information on usage of subcutaneous epinephrine was not captured on a consistent basis in their database, they cannot comment on whether it played a role in their findings.

Zaidi et al found that location of urethral opening (proximal >distal shaft) was strongly associated with urethrocutaneous fistula development. In contrast to Taicher et al., their analysis of a subgroup that underwent tubularized repair of distal urethral opening revealed no association between fistula formation and the use of caudal blocks, but found an association between fistula formation and subcutaneous epinephrine usage.29,30 Similarly, Barga et al found only an association between proximal hypospadias and fistula formation after multivariate analysis.31

A systemic review and meta-analysis of non-randomized observational studies found no association between caudal blocks and postoperative complications.32 The advantage of a meta-analysis is its ability to increase the number of observations and therefore statistical power. But we must keep in mind that meta-analysis is limited by the biases and limitations of the source data.

Caudal blocks, when compared with penile nerve block (PNB), was found to have a lower rate of hypospadias revision surgery, despite earlier reports suggesting the opposite.33

The mechanism by which caudal blocks might contribute to postsurgical complications is unclear. It has been hypothesized that blood pooling secondary to sympathectomy leads to penile engorgement, postoperative edema, and poor wound healing.26 Others would argue that increased arterial blood flow secondary to caudal block decreases tissue ischemia.33

Epidural Catheter

For painful procedures requiring an inpatient stay, or for select patients in whom longer term neuraxial analgesia is desirable, a caudal or epidural catheter is advantageous for increased duration of regional pain control. At our institution, many of our patients will be “fast tracked” after a planned repair (e.g., discharge on post-operative day one) such as an open ureteral reimplant and are more frequently given single-injection caudal blocks with an adjunct to prolong blockade. Patients who have more complex repairs and who will need a longer post-operative stay, or those with a history of pain control issues, are discussed between the urology and anesthesia acute pain teams before surgery and are given epidural catheters. This allows for continuous infusion of local anesthetic post-operatively. The epidural infusion may be paused to determine whether the patient is able to manage their pain on an oral regimen prior to discharge. Should the trial be successful, the catheter can be removed, generally the day before discharge.

Truncal Blocks

Ilioinguinal nerve block is an option for single-sided inguinal scrotal procedures when a caudal block is not appropriate due to age, anatomical challenges, or patient refusal. Pre-incisional block placement is preferable since it would allow for decrease of intraoperative intravenous analgesics usage. However, infiltration with local anesthetic may distort anatomy for the surgeon.

Medications and Adjuncts to Regional Blocks

The most common local anesthetics used in our pediatric regional anesthesia practice are ropivacaine and bupivacaine, both used at 0.125–0.25%, and given most typically at 1 cc/kg to obtain a sacral level of analgesia. Generally, we use at least epinephrine as an adjunct, which also serves to indicate if inadvertent intravascular injection has occurred. Epinephrine adjuvants intravascularly increase patient heart rate and occasionally cause EKG changes during a “test dose” (i.e. a small amount of the local anesthetic containing epinephrine, which is injected first, then followed by a short waiting period to look for any EKG or vital sign changes).

To obtain a higher level of blockade, additional injectate volume can be used by diluting the local anesthetic concentration (e.g., 1 cc/kg local anesthetic plus 0.5 cc/kg diluent such as preservative-free normal saline).

The most common adjuncts to local anesthetics used in our practice are clonidine (generally 1 mcg/kg), fentanyl (1 mcg/kg) and hydromorphone (5–10 mcg/kg). An association between caudal opioid use and increased post-operative nausea and vomiting has been noted.34 There is no significant difference in duration of action or adverse events when using clonidine vs. morphine (preservative free) as an adjunct. Thus, we limit the use of opioid as an adjunct (with or without clonidine) to patients who are at lower risk for development of post-operative nausea and vomiting and who stand to benefit more strongly from an increased duration of blockade (e.g, larger incision, more painful procedures). Clonidine is generally avoided in the neonate population due to concerns for apnea and bradycardia.

Use of dexmedetomidine as an adjunct to caudal anesthesia has been linked to higher sedation scores and higher incidence of bradycardia.35

Multimodal Analgesia

Multimodal analgesia combines the use of nerve block, opioid, and non-opioid pain medications to optimize pain control.

NSAIDs

Despite lack of strong, large-scale evidence regarding its efficacy, ketorolac is likely safe and currently is widely used in the peri-operative period.36 Ketorolac is indicated, for short-term use only, in acutely painful conditions. It is not indicated for mild pain and is contraindicated in those patients with advanced renal disease and those who are inadequately volume resuscitated. Using it at the lowest effective dose (e.g., 0.5 mg/kg IV or less) is associated with analgesia equal to higher doses but with minimal side effects. Ketorolac should also be avoided in patients at high risk of bleeding or gastrointestinal ulcer disease. Practice among anesthesiologists varies, but recent literature suggests use in healthy neonates (at least 3 weeks old and not preterm) and infants is not associated with increased adverse effects.37,38

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is the most used non-opioid analgesic in the pediatric population for treating mild to moderate pain. It is available in multiple formulations and concentrations and may be administered orally, rectally and intravenously. Dosing varies depending on route of administration, patient age and intravenous formulation available. Acetaminophen carries a low risk of serious side effects. Hepatotoxicity is the major serious side effect and is most often associated with overdose, both intentional and unintentional.39 Administration should be avoided in patients with prolonged vomiting, prolonged fasting, dehydration and hepatic impairment.40

Postoperative Concerns

PONV

One common potentially preventable side effect of surgery and anesthesia is postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV). PONV can result in significant discomfort as well as decreased patient satisfaction.41 Combination therapy is more effective than monotherapy. Anesthetic considerations to reduce the risk of PONV include regional anesthesia and multimodal analgesia to reduce the need for perioperative opioids, adequate preoperative hydration by minimizing fasting times, adequate intraoperative hydration, avoidance of volatile anesthetics, and prophylactic treatment with pharmacologic agents.42,43

Table 2 Postoperative nausea and vomiting risk factors in pediatric patients. Major risk factors are in bold and have been shown to be additive.44

| Patient | Surgical | Anesthetic |

|---|---|---|

| Female Gender after puberty | Strabismus repair | Use of volatile agents |

| Hx of PONV or motion sickness | Ear Procedures | Use of nitrous oxide |

| Age > 3 years | Tonsillectomy/adenoidectomy | Use of opioids |

| Orchiopexy | Duration of anesthetic > 30 minutes | |

| Hernia repair |

Table 3 Pharmacologic agents for postoperative nausea and vomiting prophylaxis. Ondansetron and dexamethasone are the two most commonly used agents in the pediatric population.42 Scopolamine transdermal patch typically not used in children under the age of 12 years. The British National Formulary for Children recommends the use of a quarter of a patch from the ages of 1 month to 3 years and a half of a patch from ages 3–10 years. Metoclopramide can also cause tardive dyskinesia.

| Medication | Site of Action | Dosing | Side Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | Serotonin 5-HT3 antagonist | 0.1–0.15mg/kg IV (max 4 mg) | Prolonged QT interval |

| Dexamethasone | Not well understood | 0.15 mg/kg IV | Tumor lysis syndrome |

| Scopolamine | Acetylcholine M-1 antagonist | 1.5 mg transdermal patch | Dry mouth, visual disturbances, sedation |

| Aprepitant | Neurokinin-1 antagonist | 1 mg/kg PO (max 40 mg) | Rare |

| Lorazepam | GABA agonist | 0.05 mg/kg IV (max 2 mg) | Sedation |

| Diphenhydramine | Histamine H-1 antagonist | 1 mg/kg IV (max 50 mg) | Sedation |

| Metoclopramide | Dopamine D-2 antagonist | 0.1–0.25 mg/kg IV (max 20 mg) | Prolonged QT interval |

Apnea

Former preterm infants have been found to be at increased risk for postoperative apnea. Risk for apnea diminishes for patients born at later gestational age. Cote et al found in their cornerstone study that the incidence of apnea is strongly related to gestational and post conceptual age, and that the overall incidence is markedly diminished after 43 weeks post conceptual age. In patients born at gestational age of 35 weeks, the incidence of apnea decreases to less than 5% after 48 weeks post conceptual age and to less than 1% after 54 weeks post conceptual age. In those who were born at 32 weeks, they saw a decrease in incidence of apnea to less than 5% and less than 1% after post conceptual age of 50 weeks and 56 weeks, respectively.19

General anesthesia can unmask abnormalities of ventilatory control and therefore also a propensity toward apnea not previously noted in a former preterm or even term infant. General anesthesia decreases muscle tone, resulting in upper airway obstruction which contributes to apnea; therefore, it is reasonable to infer that spinal anesthesia would decrease the risk of apnea. Davidson et al similarly found prematurity to be the strongest predictor of apnea. They saw a reduction of apneic events in the first 30 minutes, a decrease in degree of desaturation and level of intervention needed for apneic spells with awake spinal anesthesia compared to general anesthesia. They did not find a difference in the incidence of late apnea (apnea in 30 minutes to 12 hours after anesthesia). Nonetheless, their trial did not include infants born extremely premature (younger than 26 weeks gestation) or those with significant comorbidities. It is possible that the benefits of spinal anesthesia for apnea is different in those populations.45

Given the above, infants undergoing procedures requiring anesthesia (sedation, spinal anesthesia, and general anesthesia) should be admitted for observation. Admission should be for at least 23 hours following anesthesia and should include continuous pulse oximetry. Admissions requirement varies from institution to institution. Our institution has conservatively required post anesthetic admission for infants with a history of prematurity (born at < 37 weeks gestational age) who are less than 60 weeks post conceptual age. For otherwise healthy full-term infants, admission after anesthesia is not required after 44 weeks post conceptual age. Children with significant comorbidities should be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Unexpected Complications

Parents should always be prepared for possible admissions, especially in patient younger than 60 weeks post conceptual age. Moreover, patients with recent or current mild respiratory symptoms may require admission secondary to overly reactive airways.

Update on Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurotoxicity

There are ongoing concerns about anesthesia-induced neurotoxicity in the developing brain. How do we balance the potential risks associated with anesthesia and the optimal timing of surgical interventions? In animal models, including non-human primates, exposure to commonly used general anesthetic agents, such as halogenated volatiles, propofol, and ketamine, result in a range of morphologic and functional changes. Exposed animals have been found to have apoptotic neuronal cell death, glial death, impaired neurogenesis, and abnormal axon formation. In some, exposure in infancy has been associated with altered behavior, and impairment of learning and memory formation lasting into early adulthood. Exposure appears to be dose-, exposure length- and sex-dependent. Compared to their female counterparts, male rodents exhibited impairment in contextual learning and memory despite comparable neuronal cell death.46 However, it is difficult to translate results from animal models to humans since dosages used in these studies are significantly higher than those typically used for humans.47

There is mixed evidence from cohort and retrospective studies that young children exposed to anesthesia are at increased risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcomes. Some studies have suggested an increased risk of behavioral developmental disorders with multiple exposures but not with a single exposure. DiMaggio et al performed a meta-analysis of selected studies published from 2008 to 2012 and concluded that the results indicated a modest, but elevated risk.48

O’Leary et al conducted a population-based cohort study in Ontario, Canada, by linking provincial health administrative databases to children’s developmental outcomes measured by the Early Development Instrument (EDI). Children who underwent surgery before EDI completion (age 5 to 6 year) were matched to unexposed children. The primary outcome was early developmental vulnerability, defined as any domain of the EDI in the lowest tenth percentile of the population. Subgroup analyses were performed based on age at first surgery (less than 2 years and greater than or equal to 2 years) and frequency of surgery. The authors concluded that children who underwent surgery before primary school age were at increased risk of early developmental vulnerability, but the magnitude of the difference between exposed and unexposed children was small. Age less than 2 year at first exposure and multiple exposures to surgery were not risk factors for adverse developmental outcomes.49

Population-based study in Australia similarly found that among children without known preexisting neurodevelopmental disorders, those exposed to general anesthesia before age 4 years had reduced scores in reading and numeracy (mathematics) at Grade 3 and were more likely to be considered developmentally high risk (scores in the bottom 10th percentile in two or more domains) at school entry. When restricting to only one general anesthetic and one hospitalization, they saw attenuation of association to poor development and reading scores, but poor numeracy outcome remained. In contrast to O’Leary et al., they did find an association between the number of exposures and poor developmental outcomes.50

The PANDA study is a sibling-matched cohort study that compared neurodevelopment outcomes of 105 children who were exposed to general anesthesia before the age of 36 months for inguinal hernia repairs and their unexposed siblings. Neuropsychological tests were done between the age of 8-15 years. Their data showed no statistically significant difference between IQ scores of healthy children with a single anesthetic exposure before the age of 36 months compared to their healthy unexposed siblings.51 Likewise, the MASK cohort study found no evidence for a difference in test scores between children with a single anesthetic prior to the age of 3 years compared to those with no anesthesia exposure. The study, however, did find an increased risk of deficit in processing speed and fine motor outcomes among those with multiple anesthetics. Parents of the multiple exposure group reported increased problems related to executive function, behavior, and reading.52

The General Anesthesia Compared to Spinal Anesthesia Study or “GAS study” is an international prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial investigating neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 and 5 years of age after hernia repair under 60 weeks postmenstrual age. Infants were stratified by site and gestational age at birth and randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either awake-regional anesthesia or sevoflurane-based general anesthesia. Infants were excluded if they had existing risk factors for neurological injury. Results showed that exposure of just less than 1 hour to a sevoflurane general anesthesia in infancy did not increase the risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age.53 The trial similarly showed evidence of equivalence in Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence Third Edition (WPPSI-III) Full Scale Intelligence Quotient score measured at age 5 in this predominantly male study population.54

Based on the available data we can reassure ourselves and parents that among otherwise healthy young children, a single, short general anesthetic exposure will not result in worse neurocognitive development. Nevertheless, general anesthesia is not a completely benign process. There is some evidence for a detrimental effect after repeated exposures but there is still limited data on prolonged exposure and vulnerable subgroups. Most animal studies have found that longer exposures (3 hours or longer, for non-human primates 5 hours or longer) are more likely to cause neurotoxicity. However, we do not know the equivalence of animal exposure time to that of humans.55 Furthermore, we don’t yet know which is worse: multiple short exposures or a single prolonged exposure. Even still, we do not know the age at which general anesthesia no longer poses a threat to neurocognitive development of a child. For the appropriate patients and procedures, it may be wise to offer a neuraxial anesthetic technique to limit the number of potential general anesthetic exposures. If general anesthesia is required, a combined technique of regional and general anesthesia would be helpful to decrease to amount of intravenous and inhalational agents required to maintain a good level of anesthesia for the case.

Conclusion

Pediatric anesthesia is challenging in that we work with a variety of patients with not only different medical comorbidities but also with those at different neurocognitive developmental states. We are only beginning to understand the effects of anesthetics on neuroinflammation, perioperative stress and neurodevelopment. Currently, we have evidence suggesting that a short single exposure to general anesthesia in healthy young patients does not result in adverse neurocognitive outcomes. It is difficult to elucidate whether the adverse outcomes in patients who require prolonged surgeries and multiple procedures are the result of the anesthetics, changes associated with surgical-induced stress, or a marker of phenotypes predisposed to neurotoxicity. The reality is probably multifactorial. Good pre-operative communication between the urology and anesthesia teams regarding specific patient and case needs leads to optimal, individualized patient care.

Key Points

- Healthy young patients with a single, short exposure to general anesthesia are not at increased risk for deficient neurocognitive development.

- A caudal block, epidural, or truncal block provides safe and effective pain control for outpatient urologic surgeries

- Patients who will need longer-term admission after painful procedures may benefit from a caudal or epidural catheter to provide longer term analgesia

- Laparoscopic and robotic surgery creates changes in physiology which can usually be partially mitigated by the anesthesia team

- Ill children should be rescheduled if procedures are elective, but may be assessed on a case-by-case basis if symptoms are minimal

- Children at risk for postoperative apnea should be admitted for observation

- Good pre-operative communication between the urology and anesthesia teams regarding specific patient and case needs leads to optimal, individualized patient care

References

- Davis PJ, Cladis F. Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children. 2017; 9. DOI: 10.1213/00000539-199009000-00032.

- Sola C, Lefauconnier A, Bringuier S, Raux O, Capdevila X, Dadure C. Childhood preoperative anxiolysis: Is sedation and distraction better than either alone? A prospective randomized study. Paediatr Anaesth 2017; 27 (8): 827–834. DOI: 10.1111/pan.13180.

- Auerbach M, Tunik M, Mojica M. A Randomized, Double-blind Controlled Study of Jet Lidocaine Compared to Jet Placebo for Pain Relief in Children Undergoing Needle Insertion in the Emergency Department. Acad Emerg Med 2009; 16 (5): 388–393. DOI: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00401.x.

- Disease Control C for, Prevention. Chickenpox (Varicella). 2021. DOI: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-8407-4.50023-7.

- Kimberlin DW, Barnett ED, Lynfield R, Sawyer MH. Red book: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. vol. 2021, American Academy of Pediatrics; , DOI: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01642.x.

- Disease Control C for, Prevention. Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD). 2021. DOI: 10.3329/bjch.v40i2.31567.

- Mallory MD, Travers C, McCracken CE, Hertzog J, Cravero JP. Upper Respiratory Infections and Airway Adverse Events in Pediatric Procedural Sedation. Pediatrics 2017; 140 (1). DOI: 10.1542/peds.2017-0009.

- Lee LK, Bernardo MKL, Grogan TR, Elashoff DA, Ren WHP. Perioperative respiratory adverse event risk assessment in children with upper respiratory tract infection: Validation of the COLDS score. Paediatr Anaesth 2018; 28 (11): 1007–1014. DOI: 10.1111/pan.13491.

- Lema GF, Berhe YW, Gebrezgi AH, Getu AA. Evidence-based perioperative management of a child with upper respiratory tract infections (URTIs) undergoing elective surgery; A systematic review. Int J Surg Open 2018; 12: 17–24. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijso.2018.05.002.

- Saynhalath R, Alex G, Efune PN, Szmuk P, Zhu H, Sanford EL. Anesthetic Complications Associated With Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Pediatric Patients. Anesth Analg 2021; 133 (2): 483–490. DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000005606.

- Woods BD, Sladen RN. Perioperative considerations for the patient with asthma and bronchospasm. Br J Anaesth 2009; 103: i57–i65. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aep271.

- Dones F, Foresta G, Russotto V. Update on Perioperative Management of the Child with Asthma. Pediatr Rep 2012; 4 (2): e19. DOI: 10.4081/pr.2012.e19.

- Aronson S, Murray S, Martin G, Blitz J, Crittenden T, Lipkin ME, et al.. Roadmap for Transforming Preoperative Assessment to Preoperative Optimization. Anesth Analg 2020; 130 (4): 811–819. DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000004571.

- Shah NN, Vetter TR. Comprehensive Preoperative Assessment and Global Optimization. Anesthesiol Clin 2018; 36 (2): 259–280. DOI: 10.1016/j.anclin.2018.01.006.

- Practice Guidelines for Preoperative Fasting and the Use of Pharmacologic Agents to Reduce the Risk of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application to Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures. Anesthesiology 2017; 90 (3): 896–905. DOI: 10.1097/00000542-199903000-00034.

- Dobson G, Chow L, Flexman A. Practice Guidelines for Ophthalmic Anesthesia. Practice Guidelines in Anesthesia-2 2019; 6 (1): 175–175. DOI: 10.5005/jp/books/14207_19.

- Smith I, Kranke P, Murat I, Smith A, OʼSullivan G, Sreide E, et al.. Perioperative fasting in adults and children. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2011; 28 (8): 556–569. DOI: 10.1097/eja.0b013e3283495ba1.

- Dadure C, Sola C, Capdevila X. Preoperative nutrition through a prehabilitation program: A key component of transfusion limitation in paediatric scoliosis surgery. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2015; 34 (6): 311–312. DOI: 10.1016/j.accpm.2015.12.004.

- Cote CJ, Zaslavsky A, Downes JJ, Kurth CD, Welborn LG, Warner LO, et al.. Postoperative Apnea in Former Preterm Infants After Inguinal Herniorrhaphy. Survey of Anesthesiology 1995; 40 (3): 163. DOI: 10.1097/00132586-199606000-00031.

- Polaner DM, Taenzer AH, Walker BJ. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN): a multi-institutional study of the use and incidence of complications of pediatric regional anesthesia. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2012; 15 (6): 353–1364. DOI: 10.3410/f.717968230.793467936.

- Sheth KR, Batavia JP, Bowen DK, Koh CJ, Srinivasan AK. Complications in Pediatric Urology Minimally Invasive Surgery. Minimally Invasive and Robotic-Assisted Surgery in Pediatric Urology 2018; 5 (4): 381–404. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-57219-8_26.

- Joris JL. Anesthesia for Laparoscopic Surgery. Miller’s Anesthesia. Churchill Livingstone, Philadelphia, 2185-2202. 2010.

- Cyna AM, Middleton P. Caudal epidural block versus other methods of postoperative pain relief for circumcision in boys. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; 2008 (4). DOI: 10.1002/14651858.cd003005.pub2.

- Wiegele M, Marhofer P, Lönnqvist P-A. Caudal epidural blocks in paediatric patients: a review and practical considerations. Br J Anaesth 2019; 122 (4): 509–517. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2018.11.030.

- Fukazawa K, Matsuki Y, Ueno H, Hosokawa T, Hirose M. Risk factors related to accidental intravascular injection during caudal anesthesia. J Anesth 2014; 28 (6): 940–943. DOI: 10.1007/s00540-014-1840-8.

- Kundra P, Yuvaraj K, Agrawal K, Krishnappa S, Kumar LT. Surgical outcome in children undergoing hypospadias repair under caudal epidural vs penile block. Paediatr Anaesth 2012; 22 (7): 707–712. DOI: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2011.03702.x.

- Yildiz T, Tahtali IN, Ates DC, Keles I, Ilce Z. Age of patient is a risk factor for urethrocutaneous fistula in hypospadias surgery. J Pediatr Urol 2013; 9 (6): 900–903. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2012.12.007.

- Zhang J, Zhu S, Zhang L, Fu W, Hu J, Zhang Z, et al.. The association between caudal block and urethroplasty complications of distal tubularized incised plate repair: experience from a South China National Children’s Medical Center. Transl Androl Urol 2021; 10 (5): 2084–2090. DOI: 10.21037/tau-21-355.

- Taicher BM, Routh JC, Eck JB, Ross SS, Wiener JS, Ross AK. The association between caudal anesthesia and increased risk of postoperative surgical complications in boys undergoing hypospadias repair: Comment on data sparsity. Paediatr Anaesth 2017; 27 (9): 974–974. DOI: 10.1111/pan.13207.

- Zaidi RH, Casanova NF, Haydar B, Voepel-Lewis T, Wan JH. Urethrocutaneous fistula following hypospadias repair: regional anesthesia and other factors. Paediatr Anaesth 2015; 25 (11): 1144–1150. DOI: 10.1111/pan.12719.

- Braga LH, Jegatheeswaran K, McGrath M, Easterbrook B, Rickard M, DeMaria J, et al.. Cause and Effect versus Confounding–Is There a True Association between Caudal Blocks and Tubularized Incised Plate Repair Complications? J Urol 2017; 197 (3 Part 2): 845–851. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2016.08.110.

- Zhu C, Wei R, Tong Y, Liu J, Song Z, Zhang S. Analgesic efficacy and impact of caudal block on surgical complications of hypospadias repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2019; 44 (2): 259–267. DOI: 10.1136/rapm-2018-000022.

- Ngoo A, Borzi P, McBride CA, Patel B. Penile nerve block predicts higher revision surgery rate following distal hypospadias repair when compared with caudal epidural block: A consecutive cohort study. J Pediatr Urol 2020; 16 (4): 439.e1–439.e6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.05.150.

- Goyal S, Sharma A, Goswami D, Kothari N, Goyal A, Vyas V, et al.. Clonidine and Morphine as Adjuvants for Caudal Anaesthesia in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Controlled Trials. Turk J Anaesthesiol Reanim 2020; 48 (4): 265–272. DOI: 10.5152/tjar.2020.29863.

- Wang X-xue, Dai J, Dai L, Guo H-jing, Zhou A-guo, Pan D-bo. Caudal dexmedetomidine in pediatric caudal anesthesia. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99 (31): e21397. DOI: 10.1097/md.0000000000021397.

- Rowe E, Cooper TE, McNicol ED. Ketorolac for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018; 7:cd012294. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.cd012294.

- Aldrink JH, Ma M, Wang W, Caniano DA, Wispe J, Puthoff T. Safety of ketorolac in surgical neonates and infants 0 to 3 months old. J Pediatr Surg 2011; 46 (6): 1081–1085. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.03.031.

- Stone SB. Ketorolac in Postoperative Neonates and Infants: A Systematic Review. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther 2021; 26 (3): 240–247. DOI: 10.5863/1551-6776-26.3.240.

- Anesthesia BBP. Non-Opioid Analgesic Agents. People’s Medical Publishing House; 2011, DOI: 10.1016/j.mpaic.2007.11.012.

- Drugs C on. Acetaminophen Toxicity in Children. Pediatrics 2001; 108 (4): 1020–1024. DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.4.1020.

- Chandrakantan A. Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting in Children. Case Studies in Pediatric Anesthesia 2014; 7 (3): 24–25. DOI: 10.1017/9781108668736.006.

- Urits I, Orhurhu V, Jones MR. Postoperative nausea and vomiting in paediatric strabismus surgery. Br J Anaesth 2020; 105 (4): 550–551. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aeq219.

- Gan TJ, Diemunsch P, Habib AS, Kovac A, Kranke P, Meyer TA, et al.. Consensus Guidelines for the Management of Postoperative Nausea and Vomiting. Anesth Analg 2014; 118 (1): 85–113. DOI: 10.1213/ane.0000000000000002.

- Eberhart LHJ, Geldner G, Kranke P. Development and validation of a risk score to predict the probability of postoperative vomiting in pediatric patients: the VPOP score. Paediatr Anaesth 2004; 25 (3): 330–330. DOI: 10.1111/pan.12596.

- Davidson AJ, Morton NS, Arnup SJ. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Apnea after Awake Regional and General Anesthesia in Infants: The General Anesthesia Compared to Spinal Anesthesia Study–Comparing Apnea and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes, a Randomized Controlled Trial. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2015; 23 (1): 8–54. DOI: 10.3410/f.725508900.793507986.

- Lee BH, Chan JT, Kraeva E, Peterson K, Sall JW. Isoflurane exposure in newborn rats induces long-term cognitive dysfunction in males but not females. Neuropharmacology 2014; 83: 9–17. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.03.011.

- Vutskits L, Xie Z. Lasting impact of general anaesthesia on the brain: mechanisms and relevance. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016; 17 (11): 705–717. DOI: 10.1038/nrn.2016.128.

- DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Ing C, Li G. Pediatric Anesthesia and Neurodevelopmental Impairments. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 2012; 24 (4): 376–381. DOI: 10.1097/ana.0b013e31826a038d.

- O’Leary JD, Janus M, Duku E, Wijeysundera DN, To T, Li P, et al.. A Population-based Study Evaluating the Association Between Surgery in Early Life and Child Development at Primary School Entry. Obstetric Anesthesia Digest 2016; 37 (2): 78–79. DOI: 10.1097/01.aoa.0000515748.52953.0b.

- Schneuer FJ, Bentley JP, Davidson AJ, Holland AJA, Badawi N, Martin AJ, et al.. The impact of general anesthesia on child development and school performance: a population-based study. Paediatr Anaesth 2018; 28 (6): 528–536. DOI: 10.1111/pan.13390.

- Sun LS, Li G, Miller TLK, Salorio C, Byrne MW, Bellinger DC, et al.. Association Between a Single General Anesthesia Exposure Before Age 36 Months and Neurocognitive Outcomes in Later Childhood. Jama 2016; 315 (21): 2312. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2016.6967.

- Warner DO, Zaccariello MJ, Katusic SK. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Neuropsychological and Behavioral Outcomes after Exposure of Young Children to Procedures Requiring General Anesthesia: The Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids (MASK) Study. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2018; 29 (1): 9–105. DOI: 10.3410/f.733078932.793559248.

- Davidson AJ, Disma N, Graaff JC de, Withington DE, Dorris L, Bell G, et al.. Neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years of age after general anaesthesia and awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2016; 387 (10015): 239–250. DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00608-x.

- McCann ME, Graaff JC, Dorris L. Faculty Opinions recommendation of Neurodevelopmental outcome at 5 years of age after general anaesthesia or awake-regional anaesthesia in infancy (GAS): an international, multicentre, randomised, controlled equivalence trial. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature 2019; 93 (10172): 64–677. DOI: 10.3410/f.735131691.793559701.

- Creeley C, Dikranian K, Dissen G, Martin L, Olney J, Brambrink A. Propofol-induced apoptosis of neurones and oligodendrocytes in fetal and neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Br J Anaesth 2013; 110: i29–i38. DOI: 10.1093/bja/aet173.

Last updated: 2023-02-21 20:03