24: Posterior Urethral Valves and Infravesical Obstruction

阅读本章大约需要 28 分钟。

Introduction

Posterior urethral valves (PUV) remains the most common congenital cause of bladder outflow obstruction in male neonates. It is the leading cause of End stage renal disease (ESRD) in male children.1 The vast majority of cases nowadays are suspected antenatally and referred to specialist centers after birth. Additionally, there is a low threshold for investigating a male child with a urinary tract infection and therefore timely diagnosis is usually the norm. The spectrum of renal dysfunction and subsequent functional outcomes vary widely in children with this condition. PUV and its consequences, including renal dysplasia, upper tract dilatation, vesico-ureteric reflux, urinary tract infection and bladder dysfunction, accounts for 25–30% of pediatric renal transplantations in the UK (UK Transplant Registry).

This chapter aims to provide an updated overview on posterior urethral valves and how they are managed at our center.

Embryology

There are two distinct theories to explain the origin of PUVs. The first theory postulates an anomalous insertion of the mesonephric duct into the uro-genital sinus, preventing normal migration of these ducts and their anterior fusion. The other theory suggests that valves represent a persistent urogenital membrane.2 Early classification of PUV was done by Hugh Hampton Young in 1919, which described types I-III based on post-mortem dissection studies. Later studies suggested a more uniform appearance to the obstructing posterior urethral membrane and the prospective assessment of non-instrumented urethras by Dewan et al, found similar appearances in all cases studied.3 Their endoscopic appraisal revealed the membrane to attach posteriorly, just distal to the verumontanum. The membrane extended anteriorly and obliquely beyond the external sphincter with a variable sized aperture located within it, at the level of the verumontanum and they described the condition as congenital obstructing posterior urethral membrane (COPUM).

Incidence and Genetic Aspects

Commonly reported incidence of PUV is 1 in 5000 live births with 50% of these progressing to ESRD within 10 years.4 It has shown some variation with an incidence of 1:7800 in Australia and 1 in 3800 in the UK and Ireland.5,6 The understanding of the genetic basis, or potential environmental or maternal factors for this anomaly, continues to evolve. Chiraramonte et al have proposed a specific role of the short arm of chromosome 11.7 Associated anomalies will be present in about 40% of these boys mainly of the cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system and other urological conditions such as Hypospadias, Micro/ Macro phallus and anterior urethral valves.8,9,10 There have been reports of absent external auditory meatus, bilateral adrenal agenesis in boys with PUV valves.

Prenatal Diagnosis

The number of cases of PUV diagnosed prenatally has increased with the increased utilization and sensitivity of prenatal anomaly scanning. In the UK, there are at least two scans performed for pregnant women. The first is a dating scan done around 10–12 weeks gestation. The second is a more detailed anomaly scan at around 20 weeks gestation. Approximately half to two thirds of boys with PUV will be suspected prenatally. Prenatal findings on ultrasonography in suspected cases may include a thick-walled bladder, the ‘keyhole’ sign with a dilated bladder and posterior urethra, unilateral or bilateral hydroureteronephrosis, echo bright kidneys and oligohydramnios. The differential diagnosis includes prune belly syndrome, urethral atresia, bilateral vesicoureteric reflux and, less frequently, the megacystis-microcolon intestinal hypoperistalsis disorder. The recent BAPS CASS National Audit identified 35% of PUV prenatally and about 40% in the first year of life.6 This audit also has shown a statistically significant relationship between timing of diagnosis and increased risk of renal impairment.

Prenatal Intervention

Antenatal interventions for posterior urethral valves include bladder aspiration, vesico-amniotic shunt placement and fetal endoscopic valve ablation. The rationale is that early decompression of the fetal renal tract will allow improved survival with preservation of renal function, a reduction in the respiratory compromise and limb abnormalities seen in association with severe oligohydramnios. However, normal amniotic fluid volume is not a guarantee of good postnatal renal function. A study by the North American Fetal Therapy Network studied the outcome of 32 consecutive pregnancies with LUTO and normal mid-gestational amniotic fluid volume.11 Perinatal survival was 97%. Renal replacement therapy was needed where there was development of oligohydramnios and/or anhydramnios, cortical renal cysts, PUV, prematurity, and prolonged neonatal intensive care unit stay as per the univariate analysis. By multivariate analysis, the only predictor for RRT was preterm delivery.

Historically, the algorithm introduced by Johnson in 1994 has been used to select fetuses for prenatal intervention.12 The criteria include a normal male karyotype in the absence of other fetal anomalies that would adversely affect prognosis, and maternal oligo/anhydramnios or decreasing amniotic fluid volumes. could benefit from intervention. In recent years, Ruano et al proposed a patient selection model based on 4 stages of obstruction. Fetal intervention is not recommended for Stage III-IV.13

Table 1 Ruano’s staging system

| Fetal USS | Fetal Biochemistry 18-30 weeks | Possible therapies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage 1 | Normal AFI No renal cysts or dysplasia | Favorable after sequential sampling | Weekly USS monitoring |

| Stage 2 | Oligohydramnios Severe bilateral hydronephrosis Absent cysts or dysplasia | Favorable after maximum of 3 sequential samplings | Cystoscopy or Vesicoamniotic shunting |

| Stage 3 | Anhyramnios or oligohydramnios Hyperechogenic kidneys Renal cysts and/or dysplasia | Unfavorable after sequential sampling | VAS with possible amnioinfusion |

| Stage 4 | Anhydramnios and anuria after monitoring bladder filling rate. Renal dysplasia and hyperechogenic kidneys | Unfavorable biochemistry and documented anuria after monitoring for refilling | Amnioinfusion |

Favrourable biochemistry: sodium <100 mEq/L, chloride <90 mEq/L, osmolality <200 mOsm/L, and β-2 microglobulin <6 mg/L.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 10 articles on antenatal intervention for LUTO included 355 fetuses, established that overall survival was higher in the VAS group compared to the conservative group.14 Just over half (57%) survived in the VAS group versus control. Five studies showed that postnatal renal function was higher in the VAS group as compared to conservative group. Two studies involving 45 fetuses undergoing fetal cystoscopy demonstrated that perinatal survival was higher in the cystoscopy group compared to the conservative management group. Normal renal function was noted in 13/34 fetuses in the cystoscopy group versus 12/61 in the conservative management group at 6 months follow-up.

More recently, an attempt was made to address the question of benefit of prenatal intervention in the form of vesico-amniotic shunting in suspected bladder outflow obstruction. The PLUTO trial was set up as a pan-European multi-center trial.15 Entry into this trial was based on the uncertainty principle. In the event of doubt of the benefit of intervention, patients were randomized to vesico-amniotic shunting or no treatment. Outcome measures included postnatal mortality, renal function assessed by serum creatinine at age 1 year and any associated morbidity or complications of the procedure. The trial ran for 5 years but was unable to recruit the required number of patients and is now closed. Unfortunately, due to the small number of patients recruited it failed to identify if prenatal intervention is of significant benefit in treatment of suspected bladder outflow obstruction.

Neonatal Management

For those neonates suspected of having PUV prenatally, with no concerns about amniotic fluid volume, the delivery may take place outside of specialist pediatric urology centers. The priority is to drain the bladder using a size 6/8 Fr non-balloon urethral catheter. Antibiotic prophylaxis must be started, e.g., trimethoprim 2 mg/kg. A non-balloon catheter is safer than a balloon catheter especially in inexperienced hands. There is a possibility of causing urethral trauma by inflating the balloon in the posterior urethra rather than the bladder.

In those neonates where it is not possible to catheterize urethrally, usually due to either non-availability of a 6 Fr catheter or a very high bladder neck that precludes successful catheterization, a supra-pubic catheter becomes necessary. Following successful bladder drainage, close attention should be paid to urine output and electrolyte measurements as these patients may develop post obstructive diuresis resulting in abnormalities of sodium, potassium and bicarbonate levels. Creatinine should be monitored on a daily basis until a nadir creatinine level is achieved. For patients with significant renal dysfunction and electrolyte disturbance, a nephrology colleague should be involved from an early stage to optimize renal function and homeostasis.

In boys born with a history of oligohydramnios and significant pulmonary hypoplasia the priority of management is respiratory support and bladder drainage. Either a urethral or supra-pubic catheter is sufficient to optimize urinary drainage whilst awaiting homeostasis and respiratory stability.

Neonates and infants who were not suspected to have PUV prenatally may present with urosepsis, obstructive voiding symptoms, a distended bladder or palpable kidneys and the principles of management are the same. While poor urinary stream is suggestive of bladder outflow obstruction, the observation of a normal urinary stream does not exclude the diagnosis.

Confirming Diagnosis in the Neonatal Period

Once the neonate has been stabilized the diagnosis must be confirmed. Renal ultrasound scan (USS) will give information on the size and quality of the renal parenchyma, degree of hydroureteronephrosis and assessment of bladder wall thickness. It may also show a dilated posterior urethra.

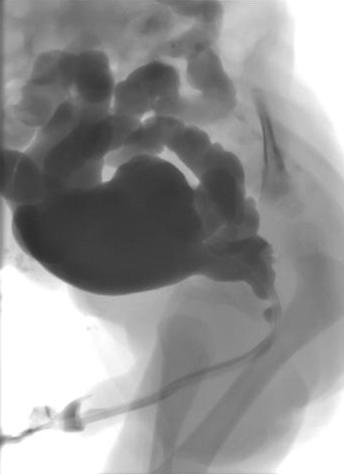

Micturating cystourethrogram (MCUG) will confirm the diagnosis and must include catheter-out views to demonstrate the caliber of the posterior urethra (Figure 1) The child is covered with a 3-day course of antibiotics to reduce the risk of infection and urosepsis.

Figure 1 MCUG demonstrating dilated posterior urethra, irregular bladder and bilateral vesico-ureteric reflux.

Additional information obtained from the MCUG includes bladder size, bladder irregularity from thickening, trabeculation and diverticula formation, vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR) and the configuration of the bladder neck. Approximately 50% of neonates with PUV will have VUR. If the VUR has been high grade and unilateral, a “pop-off” may have allowed selective dissipation of back pressure, resulting from urethral obstruction.

The VURD (valves unilateral reflux dysplasia) syndrome described by Hoover and Duckett results in very poor or non-function of the kidney on the refluxing side with a relative sparing of renal function on the contralateral, non-refluxing side.16 These authors also postulated that this mechanism of ‘pop-off’ results in long-term normal renal function, as the contralateral kidney is spared and normal. This hypothesis was subsequently challenged by Cuckow et al who showed with serum creatinine and GFR measurements that renal function was impaired in cases with VURD, implying that the protection offered by the ‘pop-off’ mechanism was not complete.17

Primary Valve Resection

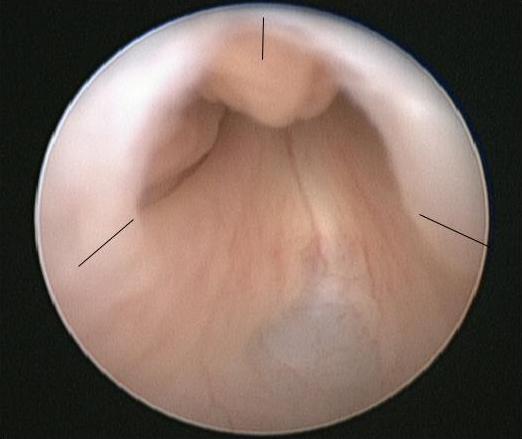

The procedure of choice for PUV is primary valve ablation which is performed once the baby is stable from a medical point of view. At induction of anesthesia a dose of intravenous antibiotic is given, e.g., co-amoxiclav 30mg/kg. The baby is placed in the lithotomy position and a diagnostic cystoscopy using 0° 6/8 Fr neonatal cystoscope performed. The posterior urethra should be carefully inspected and the valve configuration noted. The configuration of the bladder neck and appearances of the bladder and ureteric orifices should also be noted. The 11 Fr resectoscope is assembled with either the cold/sickle blade or Bugbee electrode and valve resection is typically performed at the 5, 7 and 12 o’clock positions (Figure 2)

Figure 2 Endoscopic view of PUV with the sites for valve incision marked.

A urethral catheter is placed at the end of the procedure and removed 24-48 hours later. The creatinine should be checked following catheter removal and the nappies weighed to document urine output. Antibiotic prophylaxis and renal supplements should continue until further review.

The complications of primary valve ablation include bleeding, incomplete valve resection, urethral stricture or inadvertent damage to the external sphincter. The choice of technique is dictated by the instruments available, caliber of the neonatal urethra and the size and maturity of the baby.

For preterm or very small neonates, endoscopic resection is delayed due to the difficulties of the small caliber of the urethra and potential complications of using the relatively larger instruments. These children may be managed with a urethral or supra-pubic catheter until such time as they are big enough for the procedure. As a rough guide, a body weight of 2.5 kg should allow safe and accurate PUV resection with standard endoscopic instruments.

For some small neonates there may be repeated issues with urethral or suprapubic catheters falling out, becoming blocked or dislodged or not draining adequately and in these circumstances formation of a vesicostomy may be considered the safest option to ensure adequate and continuous bladder drainage.

It is our recommendation that all boys have a follow-up cystoscopy within 3 months of the primary procedure to ensure completeness of valve ablation. This is due to the poor correlation of repeat MCUG in diagnosing residual valve leaflets and cystoscopic appraisal of residual valve leaflets requiring further resection; positive predictive valve 56%.18 However, some centers would choose to perform a repeat MCUG at this stage and proceed to cystoscopy only if the MCUG suggests persisting urethral obstruction. A further advantage of proceeding directly to check cystoscopy is that it provides an opportunity to perform circumcision which has been shown to reduce the rate of urinary tract infection by at least 83% in boys with posterior urethral valves.19 This has been validated by a recent multi center RCT, CIRCUP trial. In the study population of 91 boys, the probability of presenting with a febrile UTI was 20% in the antibiotic group versus 3% in the circumcision + antibiotic group.20

Presentation, Diagnosis and Management in the Older Child

A smaller number of patients with PUV will not present as neonates or infants but attend clinics in childhood or early adolescence with symptoms of diurnal enuresis, dribbling or poor urine stream, infection or less commonly hematuria. A careful voiding history may suggest the diagnosis and non-invasive studies, such as flow rates and measurement of post-void residual volumes, may also point to the abnormality. Urethral catheterization in the older child is invasive and fraught with difficulties; therefore, our preference is to omit the MCUG and instead, proceed directly to a diagnostic cystoscopy and primary valve ablation if the diagnosis is confirmed. Follow-up after successful complete valve ablation is as outlined below with a greater suspicion of persistent bladder dysfunction in those presenting late.

Follow-Up

Each institution will have a unique follow-up regimen for children with posterior urethral valves. However, the objectives of follow-up are:

- Optimise renal function

- Minimize urinary infections and renal scarring

- Assessment and management of voiding dysfunction with the aim of attaining total urinary continence

- Transition to adolescent and adult services

The involvement of pediatric nephrology is imperative to maximize outcomes and to ensure the correct medical management of these children.

Table 2 Example of PUV patient follow-up protocol used at Great Ormond Street Hospital, UK. FBC=full blood count, GFR=glomerular filtration rate, US=renal tract ultrasound, MCUG=micturating cystourethrogram, MSU=midstream specimen of urine to include test for proteinuria, BFA=bladder function assessment. Age defined; in infants nappy alarms and post-void residual measurements; in older children frequency-volume charts, flow studies and post void residual measurements, SPC=supra-pubic catheter.

| Creatinine & Electrolytes | FBC | Corrected GFR | US | MCUG | MAG3 | Cystoscopy/valve ablation | MSU | BFA | Video Urodynamics via SPC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 3 months | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | +/- circumcision | ✓ | ||||

| 1 year | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 2 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 3 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 4 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 5 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 6 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 7 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 8 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| 9 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| 10 years | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| 11-14 yr Annual | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| >15 yr | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | +/- | ✓ | ✓ | Adolescent referral |

Early Urinary Diversion

There is a small group of boys in whom the standard measures outlined above do not produce the desired outcome and their renal function remains fragile or deteriorates, or suffer recurrent urinary tract infections or there is significant deterioration in the appearance of the upper tracts or bladder emptying is incomplete on serial ultrasounds. The aim in these children is to maximize their renal potential and to delay or avoid renal replacement. Early urinary diversion, either by vesicostomy or bilateral ureterostomy or pyelostomy, aims to protect the upper tracts and minimize the risks of infection.

Chua et al did a retrospective review of 40 boys with either valve ablation alone or ablation + vesicostomy/ supravesical diversion. They noted that urinary diversion following valve ablation in children with stage 3 chronic kidney disease associated with posterior urethral valves may temporarily delay progression to end stage renal disease. Therefore, this may not provide any long term benefits and is more of a temporizing measure.21 This reiterates the findings of previous work by Tietjen and Lopez-Pereira at al.22,23

The concept of a refluxing ureterostomy as a form of urinary diversion has shown some promise. This is an elegant technique that allows bladder cycling to continue and at the same time dissipates the high storage and voiding pressures that are present in the valve bladder at this age. The primary requirement is a freely refluxing ureter and the procedure is carried out through a low groin skin crease incision. The ureter is identified and isolated extra-vesically in the retroperitoneum. A loop refluxing ureterostomy is then fashioned and will drain into the nappy. Unlike the end ureterostomy, reversal is relatively easy. Once the procedure has served its purpose or stops refluxing, the ureterostomy is simply closed and the ureter returned to the retroperitoneal space. The refluxing ureterostomy is particularly useful in boys with fragile renal function, as it will minimize the potential detrimental effects of the high-pressure bladder that is present in the early period following valve ablation. This is critical in the management of these neonates as renal replacement in infancy is extremely precarious and difficult to maintain.

There have been legitimate concerns that bypassing the bladder or having a continuously empty bladder may negatively impact future bladder function. Additionally, there is a lack of convincing evidence that urinary diversion improves long-term renal function.

When comparing primary valve ablation with primary vesicostomy, Godbole et al found no significant difference in serum creatinine and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) at 1 year of age between the two groups.24 The group who had vesicostomy formation as their primary procedure had been diverted for a median time of 18 months and 7 boys who had subsequent urodynamics demonstrated a normal bladder capacity. Jaureguizar et al compared bladder function outcomes in boys treated with supravesical diversion with primary valve ablation alone.25 The mean time for which supravesical diversion was present was 13 months and all were diverted in the first 2 months of life. They carried out invasive urodynamic studies at age 9–10 years and found very similar proportions of normal, poorly compliant, unstable and decompensated bladders in both groups.

More favorable bladder outcomes, improved capacity, lower detrusor end-fill pressure at expected bladder capacity, and less frequent detrusor instability have been demonstrated in 8 patients managed with primary valve ablation compared to 11 boys managed with high and low loop ureterostomy.26 The urodynamic studies were performed in these boys at a minimal mean age of 11 years and the duration of diversion was a mean of 57 months.

Thus, the place of early urinary diversion in the management of boys with PUV is limited. It has the potential to improve renal function in the short-term which is very important in boys with fragile kidney function and can defer renal replacement to a later stage. There is no convincing evidence to support its role as a way of improving long-term renal function and the jury is out on its effect on long-term bladder function. Therefore, urinary diversion must be considered in selected cases with clear goals and endpoints in mind and has a role in the management of boys with PUV.

Long-Term Outcomes: Upper Urinary Tract

Urine production begins at 8-9 weeks gestation and the collecting system is formed by the end of the first trimester. The fetal bladder can be seen soon after this on prenatal ultrasound. The presence of bladder outflow obstruction transmits raised intraluminal pressure to the developing renal parenchyma and once a critical level is reached causes apoptosis, abnormal cellular differentiation and glomerular changes that occur within the kidney. These early changes dictate the functional renal potential in later life. In cases where the obstruction is less severe or declares itself later in pregnancy, the effects of obstruction tend to be more on the bladder and renal effects are limited to dilatation of the collecting system with minimal disruption of normal nephrogenesis. An alternative or perhaps supplementary theory to explain the renal dysplasia seen in conjunction with posterior urethral valves relates to abnormal position of the ureteric bud and implantation into the metanephric blastema.27 Renal dysfunction thus appears to be the result of varying degrees of inherent dysplasia and the effects of bladder outflow obstruction. In post-natal life these effects can be further exaggerated by urinary tract infections, VUR and bladder dysfunction

When there is a significant loss of nephrons, hyperfiltration of existing functional nephrons occurs via vasodilatation of the afferent arterioles. The resultant glomerular capillary hypertension allows for normal renal function to be temporarily maintained. Over time this compensatory mechanism decompensates, glomerulosclerosis ensues, with resulting proteinuria, hypertension and a reduced glomerular filtration rate. Damage to the distal nephron impairs the concentrating ability of the kidney resulting in polyuria and polydipsia (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus), which can worsen bladder function and thereby further risk upper tract function.

The paper by Parkhouse et al is often quoted and describes the long-term outcomes of 98 boys diagnosed with posterior urethral valves presenting between 1966-1975, before the era of antenatal diagnosis.28 The follow-up period of this study ranged from 11 to 22 years. 66% of the cohort presented in the first year of life and half of the cohort of patients were managed with primary valve ablation, the remainder being diverted. 32% (31 patients) had a ‘bad long-term renal outcome;’ 10 patients died of acute renal failure, 15 developed end-stage renal disease and 6 had established chronic renal impairment over the follow-up period. Presentation under the age of one year (p<0.05), presence of bilateral vesico-ureteric reflux (p<0.0010), a plasma urea on initial discharge of >10 mmol/litre, and at age 5 years, presence of proteinuria (p<0.001) along with persistent urinary incontinence were all associated with a poor renal outcome.

More contemporary series report rather similar results. Kousidis et al reported a series of 42 patients with pre and postnatally diagnosed posterior urethral valves between 1984–1996.29 The follow-up period was 10-23 years. There were 3 (7%) deaths (2 in the neonatal period and 1 patient age 3 years following unsuccessful transplantation), 11 patients (26 %) had progressed to end-stage renal failure, one of these occurring only in the late teenage years.

In a group of 65 PUV patients presenting during 1987–2004 and followed over a shorter time period (range 1–14.3 years; median follow-up 6.8 years), Sarhan et al found a 17% overall rate of renal impairment of whom 9% had progressed to ESRD.30 Early gestational age at diagnosis (<24 weeks; p=0.003) and pre-natal oligohydramnios or anhydramnios (p=0.02) was associated with a poor outcome. There were no deaths in this group but during the same study period there were 14 fetuses with a prenatal diagnosis in which the pregnancy was terminated. Fetal urine analysis had been done in all cases and post mortem findings confirmed severe renal histological changes. This suggests that the overall incidence of renal failure, taking into account the fetuses that were terminated, is similar to the other studies mentioned above.

DeFoor’s larger group of 119 PUV patients followed for a similar length of time, (range 3–24 years; mean follow-up 7.2 years), found 13% to have developed end stage renal failure by a median age of 8.2 years (range 7 days–17.5 years).31 In this study, bladder dysfunction, necessitating clean intermittent catheterisation and/or use of anti-cholinergic medication, was associated with an increased risk of ESRD. Nadir serum creatinine > 1.0 mg/dl was also associated with an increased risk of ESRD (OR 71, CI 10–482) and this has been borne out in several previous and subsequent studies where serum creatinine <1.0 mg/dl at 1 year of age affords a good long-term renal outcome.

Heikkila et al have evaluated a larger cohort of patients (n=193) with posterior urethral valves over a much longer period of time (range 6–69 years; median follow-up 31 years).32 Rate of progression to end stage renal failure was 22.8%, with 68% developing ESRF before the age of 17 years and the remainder after the age of 17 years. The deterioration in renal function around the time of puberty in children with dysplastic kidneys is well recognized, and a likely explanation is that it represents changes within the kidney in response to growth, increased body mass and increased blood pressure.33 However, this late deterioration in renal function after puberty highlighted by this paper highlights the need for follow-up of these patients into adulthood and beyond.

Pereira et al in their series of 77 PUV cases, diagnosed < 6 months of age and followed for an average of 11.7 years, saw that 27 (35.1%) had CRF, 14 of whom were in ESRD. Of these 27 boys in CRF, 22 progressed to CRF in the first 3 years of life: 4 at between age of 15-16 and 1 at 20 years of age.34

The onset of ESRD remains unpredictable. Proteinuria can signify onset of deterioration of renal function and must be monitored. Polyuria may increase postvoid residual volumes, causing progressive uropathy and a deterioration in the concentrating ability of the renal medulla that further compounds polyuria, creating a cycle of decline. Good bladder emptying is vital; in extreme cases, overnight bladder drainage may delay renal deterioration and can improve sleep for patients with polyuria.35

Vesicoureteral Reflux

At presentation, approximately 50% of patients have vesico-ureteric reflux (VUR) on the initial MCUG. This is believed to be secondary to the bladder outflow obstruction and co-existent bladder dysfunction. Approximately 15% of patients will demonstrate unilateral high grade VUR with non-function of the ipsilateral kidney. Following valve ablation the severity of VUR may decrease or resolve completely in 25-50% of cases, and this improvement is more likely in those presenting as neonates or during infancy. Persistent VUR, especially high grade and bilateral, after successful valve ablation is associated with poor long-term renal outcome and is one of the poor prognostic indicators identified by Parkhouse et al.28 There is no longer the trend to perform anti-reflux procedures in boys with PUV, as failure rates associated with this approach are high. In cases where the grade of reflux is high and associated with poor function in the ipsilateral kidney, the capacious ureter has been used to augment the bladder in association with removal of the non-functioning kidney. Other innovative strategies include creating a refluxing ureterostomy as previously discussed and occasionally the distal ureter has been used as a Mitrofanoff channel with or without an associated anti-reflux procedure. Persistent higher grades of reflux are a potential risk factor for recurrent urinary infection and can impact negatively on transplanted kidneys and are therefore usually treated surgically prior to renal transplantation.

In a recent RCT, Abdelhalim et al, saw some improvement of reflux after valve ablation with oxybutynin. There were 24 patients in the oxybutynin arm and 25 in the control arm. Renal units in the oxybutynin group had a greater likelihood of hydronephrosis improvement (61.9% vs 34.8%, p=0.011) and resolution of vesicoureteral reflux (62.5% vs 25%, p=0.023).36

Hydroureteronephrosis

Majority of neonates presenting with posterior urethral valves will demonstrate bilateral hydro-ureteronephrosis. This is often seen to improve with initial catheterization but may temporarily worsen due to functional obstruction at the level of the VUJ by the thickened bladder wall that collapses, pinching off the ureteric orifices following catheterisation and decompression. It is important to recognize this phenomenon and occasionally this can result in anuria that lasts for 24-48 hours. The obstruction spontaneously resolves within 48-72 hours and is usually followed by post-obstructive diuresis. It is important to keep a steady nerve and resist the temptation to try and decompress the upper tracts with either internal JJ stenting or placement of nephrostomies. After primary valve ablation one should anticipate the degree of upper tract dilatation to gradually improve or resolve completely.37 This improvement will be influenced by ongoing VUR, bladder dysfunction, polyuria and abnormal ureteric motility and all these factors must be accounted for when assessing outcomes following valve ablation. Ureteric re-implantation with or without tapering is no longer performed in the context of worsening hydro-ureteronephrosis in cases of PUV as the role of the bladder and its associated dysfunction and renal tubular dysfunction with resultant polyuria have become increasingly acknowledged with improved understanding of the pathophysiology of bladder outflow obstruction.

Long-Term Outcomes: Lower Urinary Tract

The underlying etiology of bladder behavior in posterior urethral valves remains a topic of much debate. The two main culprits implicated in the etiology are that the abnormal bladder is the result of in-utero changes in response to outflow obstruction and/or that the bladder dysfunction is the result of urinary diversion. The jury is out on the second theory, as currently, the majority of cases are not diverted although the incidence of bladder dysfunction remains high. Godbole et al have shown that diversion is not necessarily detrimental to outcome of bladder function and may even improve it.24

Histologically, the obstructed bladder in fetal animal models demonstrates an increase in smooth muscle mass, an increase in the number of muscarinic receptors and increased collagen deposition. But more recent work implicates increased fibrosis in the pathogenesis of bladder dysfunction.38 A paper by one of the authors of this chapter has identified that replacement of smooth muscle with fibrosis is a major contributory factor in contractile dysfunction in the hypertonic PUV bladder. This opens the avenues for research into potential of antifibrotic agents for restoring normal contractility.39

Researchers have also demonstrated reversibility in some of these changes with removal of obstruction although recovery may be partial depending on the timing of reversal and the degree of irreversible damage that has already occurred. The early presentation that results from prenatal diagnosis allows for prompt treatment and therefore it would be reasonable to expect improved outcomes for bladder function in the current population of boys with prenatally suspected bladder outflow obstruction.

The term ‘valve bladder syndrome’ was introduced as a concept in the 1980s to encompass the abnormal voiding patterns and symptoms of voiding dysfunction, a persistent thick walled bladder, incomplete bladder emptying and associated upper tract dilatation seen in many boys with treated posterior urethral valves. Peters et al, in their cohort of 41 boys who were evaluated mainly for persistent urinary incontinence and ‘valve bladder syndrome,’ found three dominant urodynamic patterns on invasive testing; the overactive bladder and poorly-compliant blandder or acontractile bladder with some overlap between these patterns.40

Over the last 30 years clinicians have begun to recognize and understand the importance of bladder dysfunction and its impact outcome of both urinary continence and renal function in boys with posterior urethral valves. Marked differences in the technique of urodynamics, classification of different patterns and timing of examinations are seen when reviewing the literature on this topic.

Holmdahl et al followed 12 boys with PUV under the age of 15 years. Instability during urodynamic filling was observed in 2/3 of patients at 5 years of age but by puberty this had reduced.41 Bladder capacity at age 5 years appeared to be normal but after puberty capacity was shown to be approximately twice expected capacity. The urodynamic pattern changed over time with instability decreasing in favor of an over distended pattern with increasing age. This change in bladder behavior was also shown by De Gennaro et al, where 71% of 48 patients studied had abnormal urodynamic studies between ages 10 months-15 years.42 In the age group <8 years, 44% had hyper contractile and 31% hypo contractile bladders and patients >8 years demonstrated 28 % hyper contractile and 50% hypo contractile urodynamic patterns. Misseri et al demonstrated a lower rate (5.9%) of myogenic failure (acontractile or unable to generate a sustained detrusor contraction for adequate bladder emptying) in their retrospective study of 51 boys and concluded that the detrusor failure was due to co-existing anti-cholinergic treatment in their cohort of cases.43

Bladder dysfunction is key to long term renal function outcomes as illustrated in the long term follow-up study by Parkhouse et al, where the finding of incontinence at 5 years in 44% of patients, defined as not being dry during the day, was associated with a poor renal outcome in 46% of this group (p<0.001).20,24 In Ansari’s group of 227 boys with posterior urethral valves, they showed an overall 30% risk of developing chronic kidney disease with 10% progressing to end stage renal failure.1 Severe bladder dysfunction, defined as low compliance with end filling pressure >40 cm of H20 or post-void residual volume >30% or underactive detrusor or the need for CIC, was more prevalent in the patients progressing to ESRD (p<0.0001). Mazen’s study of 116 patients with PUV followed for a mean of 10.3 years (range 18 months–22 years) found 42% of patients had ESRF or had been transplanted. Urodynamic abnormalities were observed in 80% of the overall patient group and bladder instability and poor compliance were correlated with a poor renal functional outcome (p=0.04).44

In the cohort of prenatally treated PUV, the data pertaining to bladder dysfunction is scarce. Abbo et al. compared the outcome of 38 prenatally diagnosed and 31 postnatally diagnosed boys, with PUV revealing no significant difference in the incidence of voiding dysfunction (27% vs. 31%) at 7.2 years’ follow-up.45

Bladder function continues to evolve through adolescence and effective bladder management must continue into adulthood. Prostatic growth alters the dynamics of bladder outflow and the changing pattern of bladder dynamics seen in early childhood continues to change through adolescence with enlarged bladder capacity and large post-void residual volumes being most prevalent. Some young men may have to initiate clean intermittent catheterization to address this irreversible deterioration in bladder function.

Renal Transplantation

With a significant number of boys with PUV progressing to end-stage renal failure, the importance of a comprehensive bladder assessment as part of the pre-transplant work-up cannot be over-emphasized. A high pressure, poorly compliant, low capacity bladder may put at risk the transplanted kidney and graft loss becomes a real possibility. Five year graft survival rates in the PUV population have improved over the last 2 decades from 40% in the 1980s to 70% in the 1990s to near 90% in the 2000s.46

For those patients who require surgical intervention to achieve a bladder which is considered a ‘safe’ receptacle for the transplant there are divided opinions as to whether this surgery should be performed before or after transplantation. Performing bladder augmentation with/without a catheterisable conduit prior to renal transplant allows post-operative healing without immuno-suppression but risks a ‘dry cystoplasty’ which must be managed by bladder cycling and lavages especially if there is no or minimal native urine production. Additional risk with this approach is that this major surgery may tip the fragile renal function over the edge and accelerate the need for replacement therapy and temporary dialysis in the pre-emptive transplant scenario. With pre-transplant bladder augmentation any additional procedures, including transplantation itself, must not damage the vascular pedicle to the augmentation particularly when there is a short time interval between the procedures and extra care must be taken to ensure the safety of the reconstructed bladder. For those patients in whom augmentation cystoplasty is performed after renal transplantation it is important that immuno-suppression requirements have been stabilized and the improved renal function offers clear advantages. In this scenario the transplant ureter may be reimplanted into the native bladder or brought out as a cutaneous ureterostomy. Jesus and Pippi Salle concluded after a review of available literature that augmentation increases the risk of UTI after transplantation.47 They agreed that preemptive augmentation should be constructed only in selected cases, where the risks associated with increased bladder pressures exceed the ones arising with augmentation and UTIs. Knowing that a significant number of PUV boys will develop myogenic failure, augmentation can be delayed as long as they remain under close surveillance. In the context of posterior urethral valves and renal transplantation it is crucial that continued surveillance of bladder function continues after transplantation. Riley et al gives a comprehensive review of the different strategies of managing the bladder in the context of lower urinary tract dysfunction and renal transplantation.48

Fertility

There are few studies reporting on fertility and paternity outcomes in men with a history of posterior urethral valves. Persisting dilatation of the posterior urethra, damage to tissues around the verumontanum or secondary urethral strictures resulting from previous surgery will all influence the efficacy of ejaculation. Erectile dysfunction is seen more commonly in patients with chronic kidney disease and those on dialysis. In 9 patients with a history of PUV studied by Woodhouse , the semen analysis was considered within the normal range whilst in 6 men who submitted semen for analysis to Lopez Pereira, 2 patients had abnormal forms or high percentage of immotile sperm.49,50

Further Research Avenues

Posterior urethral valve management provides a lot of scope for exploration into novel strategies of prediction of outcomes and survival. A recent machine learning tool has been developed by Kwong et al to predict clinically relevant outcomes. This shows some promise and warrants further validation.51

Key Points

- Posterior urethral valves remains the most common cause of neonatal bladder outflow obstruction in males.

- An increasing number of cases are diagnosed antenatally but prenatal intervention does not appear to confer a benefit in the long-term outcome of renal function.

- Primary valve ablation is the recommended treatment of choice with diversion being reserved for specific individual cases.

- A significant number of boys with PUV will develop chronic kidney disease and end stage renal failure.

- Structured follow-up aims to prevent upper tract deterioration, prevent urinary tract infection, maximize growth and allow surveillance for bladder dysfunction in both pre and post-transplant patients with PUV.

References

- Ansari MS. Risk factors for progression to end-stage renal disease in children with posterior urethral valves. Journal of Pediatric Urology 6 (ue 3): 261–264. DOI: 10.1590/s1677-55382011000200030.

- Krishnan A, Souza A, Konijeti R, Baskin LS. The anatomy and embryology of posterior urethral valves. J Urol 2006; Apr;175(4):1214-20. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)00642-7.

- Dewan PA, Zappala SM, Ransley PG, Duffy PG. Endoscopic reappraisal of the morphology of congenital obstruction of the posterior urethra. J Urol 1992; 70: 439–444. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1992.tb15805.x.

- Casella DP, Tomaszewski JJ, Ost MC. Posterior urethral valves: renal failure and prenatal treatment. Int J Nephrol 2012; 2012 (351067). DOI: 10.1155/2012/351067.

- Thakkar D, Deshpande AV, Kennedy SE. Epidemiology and demography of recently diagnosed cases of posterior urethral valves. Pediatr Res 2014; Dec;76(6):560-3. DOI: 10.1038/pr.2014.134.

- Brownlee E, Wragg R, Robb A, Chandran H, Knight M, L. MC, et al.. Current epidemiology and antenatal presentation of posterior urethral valves: Outcome of BAPS CASS National Audit. J Pediatr Surg 2019; Feb;54(2):318-321. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.091.

- Chiaramonte C, Bommarito D, Zambaiti E, Antona V, Li Voti G. Genetic Basis of Posterior Urethral Valves Inheritance. Urology 2016. DOI: 10.1016/j.urology.2016.05.043.

- A. HS, D. RP, H. PD, L. M-JM, obstruction CWHP. Prenatal sonographic findings and clinical outcome in fourteen cases. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine 1988; 7 (7). DOI: 10.7863/jum.1988.7.7.371.

- J. C, R M. A case of hypospadias, anterior and posterior urethral valves. Journal of Surgical Case Reports 2013; 2013 (2). DOI: 10.1093/jscr/rjt003.

- L. RK, B. E, P M. Anterior and posterior urethral valves: a rare association. Journal of Pediatric Surgery 2003; 38 (7). DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00218-5.

- Johnson MP, Danzer E, Koh J, Polzin W, Harman C, O’Shaughnessy R. Natural history of fetal lower urinary tract obstruction with normal amniotic fluid volume at initial diagnosis. Fetal Diagn Ther 2018; 44 (1): 10–17. DOI: 10.1159/000478011.

- Johnson MP, Bukowski TP, Reitleman C, Isada NB, Pryde PG, Evans MI. In utero surgical treatment of fetal obstructive uropathy: a new comprehensive approach to identify appropriate candidates for vesicoamniotic shunt therapy. Am J Obs Gynecol 1994; 170 (6): 1770–1779. DOI: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)91847-5.

- Ruano R, Dunn T, Braun MC, Angelo JR, Safdar A. Lower urinary tract obstruction: fetal intervention based on prenatal staging, Pediatr. Nephrol 2017; 32 (10): 1871–1878. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-017-3593-8.

- Saccone G, D’Alessandro P, Escolino M, Esposito R, Arduino B, Vitagliano A. Antenatal intervention for congenital fetal lower urinary tract obstruction (LUTO): a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2020; 33 (15): 2664–2670. DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1555704.

- group PLUTO, M K, K K, K M, J D. PLUTO trial protocol: percutaneous shunting for lower urinary tract obstruction randomised controlled trial. BJOG 2007; 114 (7): 904–905. DOI: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01382.x.

- Hoover DL, Duckett JJ. Posterior urethral valves, unilateral reflux and renal dysplasia: a syndrome. J Urol 1982; 128 (5): 994–997. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80243-7.

- Cuckow PM, Dineen MD, Risdon RA, PG R. Longterm renal function in posterior urethral valves, unilateral reflux and renal dysplasia syndrome. J Urol 1997; 158(3: 2 1004–1007. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)64375-1.

- Smeulders N, Makin E, Desai D, P D. The predictive value of a repeat micturating cystourethrogram for remnant leaflets after primary endoscopic ablation of posterior urethral valves. J Ped Urol 2011; 7 (2): 203–208. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2010.04.011.

- Mukherjee S, Joshi A, Carroll D, al CH. What is the effect of circumcision on risk of urinary tract infection in boys with posterior urethral valves? J Ped Surg 2009; 44: 417–421. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.10.102.

- Harper L, Blanc T, Peycelon M, Michel JL, Leclair MD, Garnier S, et al.. Circumcision and Risk of Febrile Urinary Tract Infection in Boys with Posterior Urethral Valves: Result of the CIRCUP Randomized Trial. Eur Urol 2021; 22:S0302-2838(21)01993-X. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2021.08.024.

- Chua ME, Ming JM, Carter S, El Hout Y, Koyle MA, Noone D, et al.. Impact of Adjuvant Urinary Diversion versus Valve Ablation Alone on Progression from Chronic to End Stage Renal Disease in Posterior Urethral Valves: A Single Institution 15-Year Time-to-Event Analysis. J Urol 2018. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.024.

- Tietjen DN, Gloor JM, Husmann DA. Proximal urinary diversion in the management of posterior urethral valves: is it necessary? J Urol 1997; 158: 1008–1010. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-3468(98)90257-3.

- P LP, L E, MJ MU, R L. Posterior urethral valves: prognostic factors. BJU Int 2003; 91: 687–690. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)61251-7.

- Godbole P, Wade A, Mushtaq I, Wilcox D. Vesicostomy vs. primary valve ablation of posterior urethral valves: Always a difference in outcome? J Ped Urol 2007; 3: 273–275. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2006.11.007.

- Jaureguizar E, Lopez Pereira P, Urrutina MJM, L E. Does neonatal pyeloureterostomy worsen bladder function in children with posterior urethral valves? J Urol 2000; 164: 1031–1034. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200009020-00027.

- Podesta M, Ruarte A, Garguilo C, R M. Bladder function associated with posterior urethral valves after primary valve ablation or proximal urinary diversion in children and adolescents. J Urol 2002; 168: 1830–1835. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210020-00042.

- Henneberry MO, Stephens FD. Renal hypoplasia and dysplasia in infants with posterior urethral valves. J Urol 1980; 123: 912–915. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56190-x.

- Parkhouse HF, Barratt TM, Dillon MJ, al DPG. Long-term otcome of boys with posterior urethral valves. Br J Urol 1988; 62: 59–62. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb04267.x.

- Kousidis G, Thomas DFM, Morgan H, N H. The long-term outcome of prenatally detected posterior urethral valves:10 to 23 year follow-up study. BJU Int 2008; 102: 1020–1024. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2008.07745.x.

- Sarhan O, Zaccaria I, Macher M, F M. Long-term outcome of prenatally detected posterior urethral valves: a single centre study of 65 cases managed by primary valve ablation. J Urol 2008; 179 (1): 307–312. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.08.160.

- DeFoor W, Clark C, Jackson E, P R. Risk factors for end stage renal disease in children with posterior urethral valves. J Urol 2008; 180: 1705–1708. DOI: 10.1016/s0084-3954(09)79530-2.

- Heikkila J, Holmberg C, Kyllonen L, al RR. Long term risk of end stage renal disease in patients with posterior urethral valves. J Urol 2011; 186: 2392–2396. DOI: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.07.109.

- Celedon CG, Bitsori M, Tullus K. Progression of chronic renal failure in children with dysplastic kidneys. Pediatr Nephrol 2007; 22: 1014–1020. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-007-0459-5.

- P LP, MJ MU, L E, E J. Long-term consequences of posterior urethral valves. J Pediatr Urol 2013; Oct;9(5):590-6. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.06.007.

- Nguyen MT, Pavlock CL, Zderic SA, Carr MC, Canning DA. Overnight catheter drainage in children with poorly compliant bladders improves post-obstructive diuresis and urinary incontinence. J Urol 2005; 174 (1633). DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000179394.57859.9d.

- Abdelhalim A, El-Hefnawy AS, Dawaba ME, Bazeed MA, Hafez AT. Effect of Early Oxybutynin Treatment on Posterior Urethral Valve Outcomes in Infants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Urol 2020; Apr;203(4):826-831. DOI: 10.1097/ju.0000000000000691.

- Farhat W, McLorie G, Capolicchio G, A K. Outcomes of primary valve ablation versus upper tract diversion in patients with posterior urethral valves. Urology 2000; 56 (4): 653–657. DOI: 10.1016/s0090-4295(00)00784-6.

- Metcalfe PD, Wang J, Jiao H, Huang Y, Hori K, Moore RB. Bladder outlet obstruction: progression from inflammation to fibrosis. BJU Int 2010; 106 (1686). DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2010.09445.x.

- Johal N, Cao K, Arthurs C, Millar M, Thrasivoulou C, Ahmed A, et al.. Contractile function of detrusor smooth muscle from children with posterior urethral valves - The role of fibrosis. J Pediatr Urol 2021; 100 (e1-100.e10). DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2020.11.001.

- Peters CA, Bolkier M, Bauer SB, WH H. The urodynamic consequences of posterior urethral valves. J Urol 1990; 144 (1): 122–126. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)39388-6.

- Holmdahl G, Sillen U, Hanson E, G H. Bladder dysfunction in boys with posterior urethral valves before and after puberty. J Urol 1996; 155: 694–698. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66502-9.

- M G, G M, ML C, M S. Early detection of bladder dysfunction following posterior urethral valves ablation. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1996; 6: 163–165. DOI: 10.1055/s-2008-1066497.

- Misseri R, Combs AJ, Hrowitz DJM. Myogenic failure in posterior urethral valve disease: real or imagined? J Urol 2002; 168: 1844–1848. DOI: 10.1097/00005392-200210020-00045.

- Ghanem MA, Wolffenbuttel KP, Vylder A, Nijman RJM. Long-term bladder dysfunction and renal function in boys with posterior urethral valves based on urodynamic findings. J Urol 2004; 171: 2409–2412. DOI: 10.1097/01.ju.0000127762.95045.93.

- Abbo O, Bouali O, Ballouhey Q, Mouttalib S, Lemandat A. Decramer S, et al.\[Is there an outcome difference between posterior urethral valves diagnosed prenatally and postnatally at the time of antenatal screening?\. Prog Urol 2013; 23: 144–149.

- Marchal S, Kalfa N, Iborra F, Badet L, Karam G, Broudeur L, et al.. Long-term Outcome of Renal Transplantation in Patients with Congenital Lower Urinary Tract Malformations: A Multicenter Study. Transplantation 2020; Jan;104(1):165-171. DOI: 10.1097/tp.0000000000002746.

- Jesus LE, Pippi Salle JL. Pre-transplant management of valve bladder: a critical literature review. J Pediatr Urol 2015; Feb;11(1):5-11. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2014.12.001.

- Riley P, Marks SD, Desai D, I M. Challenges facing renal transplantation in pediatric patients with lower urinary tract dysfunction. Transplantation 2010; 89 (11): 1299–1307. DOI: 10.1097/tp.0b013e3181de5b8c.

- Woodhouse C, Reilly JM, Bahadur G. Sexual function and fertility in patients treated for posterior urethral valves. J Urol 1989; 142 (2 part 2): 586–588. DOI: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38824-9.

- P LP, M M, MJ MU, JA M. Long-term bladder function, fertility and sexual function in patients with posterior urethral valves treated in infancy. J Pediatr Urol 2011. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.11.006.

- Wong JC, Khondker A, Kim JK, Chua M, Keefe DT, Dos Santos J, et al.. Posterior Urethral Valves Outcomes Prediction (PUVOP): a machine learning tool to predict clinically relevant outcomes in boys with posterior urethral valves. Pediatr Nephrol 2021. DOI: 10.1007/s00467-021-05321-3.

最近更新时间: 2023-02-22 15:40